November 14, 2016

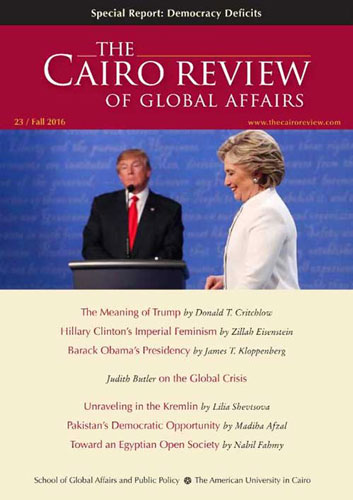

The day before America’s presidential election, the American University in Cairo hosted a mock vote. My colleagues from the Cairo Review of Global Affairs handed out ballots to students. It was part of a promotional effort for the Fall 2016 issue, which focuses on “Democracy Deficits,” in America, Russia, Pakistan, and elsewhere.[1] Lo and behold, of the 135 students who voted, Donald J. Trump emerged as the victor with 42 percent of the vote. This balloting foreshadowed America’s own unexpected result. It also captured Egypt’s interest in Trump, which parallels the rapport that the business tycoon and Egyptian President Abdul-Fattah El-Sisi seem to have developed. Even though little is known of how a President Trump will approach the Middle East, Egyptians are eager for a change from the Obama administration’s perceived dithering.

As Americans stood in winding lines at polls across the country, more than 500 guests gathered at the Nile Ritz Carlton to celebrate whatever and whomever was to come in that faraway bastion of democracy. The reception began at 9pm on Tuesday evening (early afternoon EDT). After entering the gilded lobby of the recently remodeled grand hotel and passing a wall of ancient pharaonic reliefs, honored guests were treated to another layer of security. Then cardboard standups of Hillary Clinton, Donald J. Trump, and Barack Obama warmly welcomed the attendees. Plenty of glittery party favors and red-white-and-blue balloon colonnades confirmed the importance of the occasion, and the cash bar suggested that this was indeed a U.S. Government affair. Inside the hotel’s neo-Andalusian ballroom, four giant screens projected CNN, BBC, and a slideshow of Americana (Lincoln’s mug alongside old campaign ads from the 19th and 20th centuries). Embassy officials circulated, making sure that guests knew that they could go outside for a cigarette, though would then have to go through security yet again.

Scores of college students lined up to take selfies with the American ambassador. Businessmen and women ate eggrolls with duck sauce and mini-kabobs and shrimp. Egyptian youths who had participated in the Model U.S. Congress or had joined one of the dozens of exchange programs that Washington funds were there. Vocal jazz played as we all gazed at the news-tickers, though there was not yet any news. Waiters passed mango juice and soda. The chandeliers were faux crystal. It was a wedding reception without a bride or groom.

I didn’t recognize many of the VIPs who were intermingled with the American journalists, USAID contractors, marines, and others. Some local artists or activists might avoid a party like this for fear of associating with America, but that didn’t stop many others like the researcher for a leading local human rights organization or editors of local newspapers. I did see the 77-year-old Saad Eddin Ibrahim, a democratic crusader against Hosni Mubarak who was often in and out jail in the 2000s.

As midnight rolled around, a cartoonist for the state newspaper Al-Akhbar professed his support for Trump. His reasoning, which approximates many Egyptians’ perspectives on the matter including most likely President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi himself, is that Trump would be tough on terrorism and overlook human rights concerns. Whether right or wrong, the perception here is that Hillary Clinton is a Muslim Brotherhood sympathizer, that the Obama administration created ISIS among other conspiratorial shenanigans. Some of this skepticism derives from America’s alleged support for the Brotherhood-affiliated Mohammed Morsi during his abortive presidency. (The photo of Hillary and Morsi reinforces this impression.) Then there’s the fact that Washington was slow to embrace Sisi’s overthrow of Morsi in the summer of 2013, a hesitation that confirms to many that the U.S. is in the pocket of Big Brotherhood.

I have given up trying to debunk these conspiracy theories. The fact that the cartoonist who thrilled to the prospect of a Trump Presidency had himself been on an exchange program to America in 2009, that he had visited Washington during Obama’s presidency, suggests to me that much of the country’s—and the Embassy’s—public diplomacy is a waste of time and money. “It sounds trite but it’s an important event that we like to share,” a senior embassy official told me of the election viewing party. In truth, neither hearts nor minds are won by a bilingual Twitter feed or Facebook Q&As with officials—or even a lavish election viewing party.

In a huddle with foreign correspondents, sipping our bounty from the cash bar, we discussed the stability of the Sisi government, the likelihood of a countrywide demonstration in response to the cash crunch. A day of protests had been scheduled for Friday, November 11, a catchy sounding date (11/11) that has been widely discussed in the local media. Many broadcasters and cartoonists took the opportunity to assail the Muslim Brotherhood for planning the protests, although no proof of their role in the planning had been found. Among our circle of colleagues, someone suggested that this might be a state security ploy, a sort of self-built safety valve by the government to ensure that no actual protests were planned and which might challenge the state’s legitimacy. The discussion turned to the policies of Sisi’s government, and how much of it he actually controls. It’s an Egyptian version of Kremlinology, and few know which security apparatuses actually fall under his purview.

I left by 12:30, knowing that there would be a free continental breakfast starting at 6am at the Ritz, by which time we might know the name of the new ruler of the free world.

* * * *

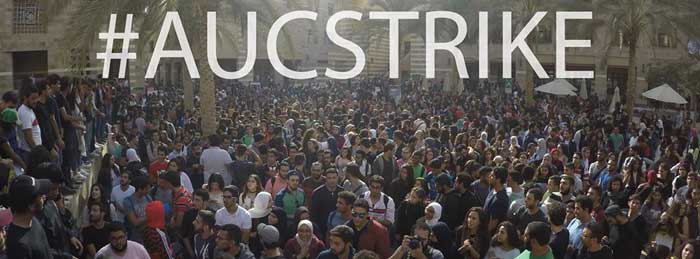

While students at the American University in Cairo voted on Monday, a spontaneous act of democracy erupted across the neo-Oriental college campus. The university’s recently inaugurated President, Ambassador Francis J. Ricciardone Jr., held a special meeting for the AUC community titled, “Implications of Floating the Egyptian Pound.” The event’s innocuous description (“a series of discussions about the impact of the economy on AUC”) seemed to obscure the real damage that had been wreaked on the Egyptian economy a week earlier. The Egyptian government had, at long last, let its weakened currency, the Egyptian pound, float. State institutions would no longer set the rate against the dollar, an untenable situation that had resulted in a huge gap between the official exchange (8.88 EGP to USD) and black market prices (which edged toward 18 EGP to USD). Within hours of floating, the countries’ Egyptian pound bank accounts essentially converted into monopoly money. Though not “official,” the generally accepted exchange rate set by so-called market forces fell (from an Egyptian perspective) to about 16.5 EGP to USD.

Surely it’s in the country’s long-term best interest to float the pound. But why did this momentous change come about at this moment? In a sense, the timing couldn’t be worse: the devaluing of the pound has occurred in the face of severe shortages of sugar and rice. Perhaps the government saw no better time to cut its losses and seek a much needed grant from the International Monetary Fund, a condition of which was that the pound be left to sink or swim on the market. Citizens are angry but, without a freely operating parliament and without the right to protest in public spaces, how can they respond? Neither the minister nor the president held a press conference to allay citizens’ fears about the Egyptian pounds free fall. Now petroleum prices are spiking which will affect the price of all goods and services in the economy.

Egypt today is a radically non-transparent nation where the decision to float the Egyptian pound was not vetted by legislators or part of a national discussion. Of course Sisi was democratically elected by a large margin in May 2014, but in the years following the popular uprising there has been little change in the foundations of the economy. Experts routinely describe what effectively amounts to an oligarchy, with former military officials heading all major sectors.[2] So when there was an infant formula shortage in September, the Ministry of Health asked for the Army’s help in importing a good in high demand.[3]

The university—which sits on the edge of Cairo’s sprawling suburbs and the empty desert—mirrors some of the peculiarities, hierarchies, and contradictions of the country writ large. AUC’s bylaws require an American president and its orientation is that of an American liberal arts college, and yet its student body is almost entirely Egyptian. Its campus moved from historic downtown Cairo to the outskirts of the city’s suburbs in 2007 ostensibly to better accommodate its students with state of the art labs and facilities—in order to compete with new colleges popping up in the Emirates and Qatar. But since 2011, the international student body and cohort of American study-abroads—its primarily source for cash flow—has dissipated. That financial hit is compounded by the construction of a massive new campus. As a result, AUC has instituted hiring freezes and denied annual raises for faculty even though these included in their contracts. Scholarships have been slashed, class sizes have grown, and throughout it all the students have been squeezed, all of which are factors that have affected its previously top-notch ratings.

Rising tuition fees have long been a red line for students. In fall 2012, after then President Lisa Anderson announced an 8 percent tuition hike, a student strike shuttered the campus for a full 10 days.

The AUC discussion was meant to be an information session about what the rate change meant for tuition. But the room chosen was too small for the crowd of students who had hoped to attend, which already raised the temperature. As Ricciardone and other administrators explained the dollars and cents of the matter, the huge losses the university was facing, his condescending tone offended the student body. “There is no such thing as a free lunch, and understanding that is part of becoming an adult,” said Ricciardone. A student fired back: “Is my tuition going to go up by LE35,000 next semester? Yes or no? And I don’t know is not an answer.” Ricciardone dismissed the question as “ridiculous,” which led students to chant that he resign. They stormed out of the conference room and began to organize a sit-in on the plaza leading to the university’s Administration Building.[4]

I found the November student strike to be particularly noteworthy given that there are few other spaces in the country today where the victims of economic crisis can voice their concerns with confidence that they will not be incarcerated. It has always been easy to dismiss the activism of the AUC’s students, a sentiment reflected in a comment I overheard from a senior administrator who hails from North America the next day. “Our students are quite wealthy,” he said. “When they were protesting five years ago they parked their Lamborghinis on the flower beds and blocked the [university’s] gates.” But in such a stagnant political environment, universities represent a space where political expression is freer and thus has the potential to be more outrageous. Unlike the state-run Cairo University, police are unlikely to break up the sit in. At the campus of an American-style university with an American president at its helm and funding from USAID among others, there exists a small opening for dissent for Egyptian students who have few other forums for expressing their opinions, except on social media. They chanted in Arabic, representing in what might be the largest demonstration the country has seen since Sisi’s government effectively outlawed protests in fall 2013.

Meanwhile, security presence was high across Cairo but the mass protests scheduled for Friday, November 11, never panned out. Most downtown establishments closed for the today just in case.

By Monday, after a weekend sit-in, the students’ demonstrations at AUC had quieted down. The university administration is seeking a compromise with the students and will keep the pre-float exchange rate for fall tuition payments—a small victory for the students amid nation-wide crisis that has only just begun.

* * * *

On Wednesday morning, the American ambassador was scheduled to speak at 7:30 a.m. but he ended up taking to the lectern an hour late.

A senior embassy official and I kibitzed, both of us equally perplexed as to who in the hell the new president might rely on for Middle East counsel. Apparently candidate Trump’s counter-terrorism advisor Walid Phares, whose resume includes time with a Lebanese militia, had passed through Egypt recently for some official meetings without letting the embassy know.[5] Otherwise, 120 Republican foreign policy experts had signed a “Never Trump” open letter. As such, a Trump administration might necessarily break from establishment views.

Attendees were focused on the large screens in the Ritz ballroom. I heard CNN commentator and former Obama official Van Jones say, “There are people around the world who are appalled and shocked… Some are laughing.” Not so in Egypt, where many were eager to welcome a President Trump, eager for a change from is perceived as Obama’s enfeebled approach to the region.

When he took the stage, His Excellency the U.S. Ambassador sought to allay the fears and anxieties of the audience, smaller than the night before but still numbering in the hundreds. A dozen video cameras represented all the big stations. The ambassador noted that there would be a “smooth transition” of power. In his one-minute speech, the ambassador added that the new president would “recognize the importance of Egypt in the world.” That point seemed to be validated by Trump and Sisi’s chummy meeting at the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly in September.

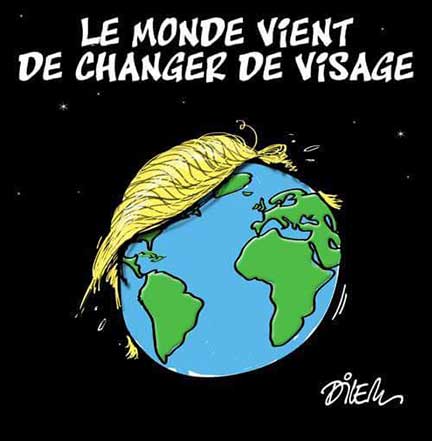

It is no coincidence that yesterday Sisi was the first foreign leader to congratulate Trump. For his part, Trump has called Sisi, “a fantastic guy.” The Egyptian state’s flagship newspaper—which has lambasted, derided, and lampooned Obama in a myriad of caricatures—published a laudatory drawing of Trump. Holding out a hand with one thumb up, Trump stands confidently, his features exaggerated by not in a negative way. “I have arrived,” he says.

I have been surprised that Egyptian commentators have seemingly ignored Trump’s Islamophobic and bigoted comments. What of Trump’s pledge from a year ago to create a registry for Muslims? Even Egypt’s president dismissed it as bluster. “It is important for us to know that during campaigns many statements are made and many statements are said,” Sisi told CNN in September.[6]

Reflecting on Trump’s temperament, other cartoonists were quick to mock America’s president-elect. “By God, you’re the real boss,” says Sisi to his orange counterpart in Andeel’s cartoon contribution to the independent Egyptian outlet Mada Masr. (Perhaps it’s a sneak peek of Trump’s forthcoming Cairo visit?) Buildings behind them smolder; the city is a hot mess, a veritable dumpster fire. So the two men roll up their sleeves. But one wonders if they are more likely to stoke the flames than to extinguish them.

That sentiment is similarly rendered in a multi-panel gag from the Egyptian comic artist Islam Gawish, who imagines President Trump getting his hands on the nuclear code. “Sir, this is your nuclear briefcase,” says the assistant. “This button is to strike Iran. And that’s for Russia and that’s to strike the Middle East and…” “Let me try,” says a bug-eyed Trump. He clicks SELECT ALL. The assistant runs off as quickly as he can.

I chuckled when I read a frame by the Egyptian cartoonist Abdallah for the independent daily Al-Masry Al-Youm. A bald man sits in a barber’s chair. “Give me a Donald Trump,” he says to the perplexed coiffeur. The punch line pushed me to think how Trump was elected—so many in America wished they had his wealth, his power, and his hair.

Scores of Arab friends took to social media to incessantly mock the U.S., making jokes along the lines of “America is not ready for democracy.” Others were genuinely frightened about the apparent rise in hate crimes and the mainstreaming of anti-Muslim rhetoric.

For all of the bewilderment across the spectrum, I found that humor offered a source of hope, however small. Satire was a way to work through the Trump’s upset. “The upside of the US elections is hearing BBC reporters talking to Americans with the patronizing tone they normally use in the Middle East,” quipped the ever-irreverent Karl Sharro, a Lebanese-British jokester, on social media.

It was harder to laugh, however, when he said this: “Congratulations America, you have elected the kind of ‘strongman’ the US has been supporting around the world for decades. We sympathize.”

_______________________________________

[1] The full issue is available online: https://www.thecairoreview.com/fall-2016/

[2] See for instance: Abigail Hauslohner. “Egypt’s ‘Military Inc’ Expands its Control of the Economy,” The Guardian, 18 March 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/mar/18/egypt-military-economy-power-elections

[3] Tarek El-Tablawy. “When the Baby Milk Disappeared, Egypt Turned to the Military,” Bloomberg, 9 September 2016. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-09-08/when-the-baby-milk-disappeared-egypt-turned-to-the-military

[4] AUC Students Storm Out of Meeting with New President Over Tuition Fee Hikes, Mada Masr, 7 November 2016. http://www.madamasr.com/en/2016/11/07/feature/economy/auc-students-storm-out-of-meeting-with-new-president-over-tuition-fee-hikes/

[5] On Phares’s nefarious background, see: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2016/03/22/the-dark-controversial-past-of-trumps-counterterrorism-adviser/

[6] “Egypt’s Sisi Comments on Trump’s Proposed Ban Against Muslims in CNN Interview,” Ahram Online, 21 September 2016. http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/1/64/244366/Egypt/Politics-/Egypts-Sisi-responds-for-first-time-to-Trumps-prop.aspx