TBILISI — Vasily is a drifter. He was adopted from an orphanage at the age of five in 1979, the year the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan. In his childhood city of Ukhta, in the far northern Komi Republic, he was kicked out of the Young Pioneers, the compulsory Soviet youth program, for heckling at assemblies. He flunked out of school just before the USSR collapsed and spent his 20s in a country that had just embraced anarchic capitalism, engaging in, as he described it, “sex, drugs, and rock and roll.”

He dated the daughter of a local mobster who blew himself up with a grenade after a Scarface-style shoot-out with police. He spent his 30s selling ice cream and printing out horoscopes in the Black Sea coastal city of Sochi. For the last 10 years, he worked as an assistant at an archeological institute in Moscow. Now, in Georgia’s capital, Vasily—who asked to be referred to by this pseudonym—cleans the apartments of younger and more affluent Russian émigrés who also fled Russia after it launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

Vasily’s rootless habits made his departure from Russia, just two months after the invasion, all the easier. The 45 year-old with deep blue eyes and dirty blonde bangs parted down the middle is part of an underrepresented demographic of post-invasion Russian émigrés born before the year 1980.

The average age for recent émigrés is 32, according to Outrush, a sociological project that researches the current migration wave from Russia. Another survey conducted by a similar project, After 24, revealed that 1 percent of post-invasion Russian migrants residing in Georgia and Armenia were born in the 1960s, 6 percent in the 1970s and 59 percent in the 1990s. Most of this group likely lives either in Georgia or Armenia, due to those countries’ visa-free regimes for Russian nationals, direct flights to Russia and widespread use of the Russian language.

For younger émigrés—many with the ability to switch careers, work remotely or obtain additional education—emigration can be experienced as a fresh start. But for older exiles, the prospects of applying for European humanitarian visas in countries farther west can be daunting, and their typically more traditional jobs that predate the gig economy can limit their mobility.

In Tbilisi, some like Vasily have found low-skilled labor jobs through Russian-speaking listings on Telegram. Others, such as a couple named Vlada, 50, and Sergei, 73—both teachers from St. Petersburg who also asked to be referred to by pseudonyms––continue to teach at private, Russian-language schools opened by émigrés. Vyacheslav Ivanets, 46, a lawyer from Irkutsk who defended political activists in Russia, now offers legal advice to Russian-speaking clients relocating businesses to Georgia.

They came for different reasons. Vyacheslav fled Russia over safety concerns tied to his profession. Vasily, Vlada and Sergei left because they could no longer contain feelings of revulsion prompted by seeing friends and colleagues plunge into political apathy or even full-fledged support for the war.

All four repeated one thing about their transition to Georgia: Despite the difficulties emigration brings, here they can breathe air unpolluted by the militarism and the fear they left behind.

Perceptions of the 1990s

What makes middle-aged exiles different is that unlike most Russian émigrés who spent their adult lives under one president, they remember a decade in the Russian Federation without Vladimir Putin.

The Russian public’s perception of the 1990s is sharply divided. Some remember ubiquitous bread lines, runaway inflation and seemingly unhinged criminality that swept the streets—a perception the Kremlin has amplified and weaponized over the years to bolster the impression of new stability under Putin. Others, typically more cosmopolitan and educated, remember it as a time of unhindered freedom of expression.

Vlada, a schoolteacher whose mother held “dissenting views” and listened to clandestine broadcasts of Radio Liberty in Soviet times, is one of the latter.

“The fact that [previously banned] writers like [Aleksandr] Solzhenitsyn and [Varlam] Shalamov were suddenly being published was a breath of fresh air,” she told me in the crammed, low-ceilinged kitchen of her Tbilisi apartment. Her short hair was dyed pink, and pomegranate-shaped earrings dangled from her ears.

“Yes, materially, we lived poorly,” she added. “But we also lived poorly in the Soviet Union, so I did not see the empty shelves in the stores as much of a tragedy. At least we could live freely, and it was a culturally interesting time.”

I met Vlada and her second husband, Sergei––a science teacher and “pop science” astronomer—in their newly rented apartment, perched over a steep incline below the Old Town funicular. The trek up is not easy––the steep steps take the wind out of you. But the couple remains full of vigor.

“For me, the Soviet Union, especially during its final years, felt like an abnormal phenomenon, so I welcomed the normality that its collapse was supposed to bring,” said Sergei, who lived the better part of his life as a Soviet citizen.

With a pair of square glasses and a neatly trimmed grey beard, he wore a shirt from Nochlezhka, a St. Petersburg homeless shelter opened by Girgory Sverdlin, a civil-society activist who now helps military deserters flee Putin’s war.

“We had a chance in the 1990s to join the ‘normal world,’ but somehow it slipped away from us,” he continued. “Now I feel a sort of dosada,” he said, placing special emphasis on the Russian word that loosely translates as “vexation” or “frustration.”

But even during most of the two decades under Putin’s rule, Vlada and Sergei were able to live what they characterize as a politics-free “normal life.”

“While my mother was always very politicized, I did not care much about politics,” Vlada told me. “I had children at a very young age, so I guess I was just busy taking care of them. I was happy, just happy with the opportunities to travel abroad and work a favorite job.”

Vasily’s perception of the 1990s, like Vlada’s, was positive. Still young at the time, he characterizes the decade as total kaif, using a dated slang term that roughly translates to, “cool” or “bliss.”

He entertained me with wild stories about his young adulthood, speaking in the kitchen of an apartment I was subletting in Tbilisi for a month, which he came to clean.

Even though he had a firsthand encounter with criminality––dating the daughter of a mobster who kept “suitcases filled with cash scattered across the apartment”—he seemed unfazed.

“This was just part of everyday life in the 1990s and early 2000s in a northern Russian city,” he said. “But because we were young, we didn’t really reflect much on it. We were just having fun.”

He continues having fun to this day, apparently untethered by obligations. He has a 20-year-old son still in Russia but doesn’t worry about him much.

“His stepdad is a millionaire,” Vasily said. “He’ll save him from the draft.”

“My whole life was just preparation to get the f**k out of Russia,” he concluded. “I had no ties to the country. My adoptive parents are dead, and all my ex-wives are living on inheritance.”

Life under Putin

The collapse of the Soviet Union and its uniform state-run education system prompted the establishment of the kind of private schools where Vlada taught for years. Most recently, she taught at a small Montessori school in St. Petersburg.

While the Soviet system prided itself on high-quality education, public, state-funded schools in the post-Soviet Russian Federation deteriorated, Sergei and Vlada both told me. And since 2014—when Moscow illegally annexed Ukraine’s Crimea region and fomented a separatist conflict in parts of eastern Ukraine—they have increasingly become vehicles of Kremlin propaganda.

Shortly after the 2022 invasion, the government passed a law requiring state schools to conduct weekly Important Conversations––ideological seminars aimed at promoting “national unity, patriotism and traditional values.” In some of these Important Conversations, veterans of the so called special military operation––the Kremlin’s mandatory euphemism for its invasion of Ukraine—were brought in to regale the schoolchildren with tales of battlefield heroics.

“After the start of the war, we had an influx of parents bringing their children to our school simply because they wanted to shield their kids from all of this propaganda,” Vlada told me.

She stayed in Russia for over a year after the start of the invasion, she said, partly to “provide schoolchildren a reprieve from [the militarism]” as long as she could.

For her husband Sergei, whose career in the hard sciences existed in a relatively depoliticized space, the biggest impact of Putin’s isolationist policies was their severing of international networks crucial for scientific research.

Since the 1980s, he had worked at the Pulkovo astronomical observatory near St. Petersburg—part of the state Russian Academy of Sciences––conducting research on optics to improve the efficacy of telescopes. He also ran a widely popular vlog about astronomy in which he would try to instill in audiences the idea that “science is a human, international” practice that should not be confined by any nation.

You have to fight for your place here, and I am lucky to still be at an age where I have the strength for it. If I were 10 years older, I wouldn’t have risked it.

By contrast, Vasily—who also worked for the Academy of Sciences in its Moscow-based Institute of Archeology—acutely felt the regression his country was undergoing.

In 2011, when Putin’s Russia was going through a wave of politicization––spurred by Putin’s decision to return to the Kremlin for a third presidential term––Vasily moved to the capital to commit to his first long-term work on excavations as an assistant at the institute. For 11 years until his recent departure from Russia, he would clean and polish artifacts rescued from various sites across the country before companies could tear up land for new high-rises, shopping malls or oil pipelines.

One expedition left a particularly strong impact on him, forcing him to confront trends he had previously ignored. In 2020, he was part of an expedition to the Taymyr Peninsula on the far northern coast of the Arctic Ocean, “a place where the sun never sets in the summer and where it was impossible to sleep,” he said.

The peninsula is home to the Dolgan and Nenets indigenous groups and, from the Soviet era until 2005, was part of a federal region called the Taimyr Dolgano-Nenets Autonomous Okrug. During Putin’s first presidential tenure, however, the Taimyr Autonomous Okrug was merged into the larger Krasnoyarsk Krai federal subject in a controversial move seen as a way for Moscow to expand its resource-extraction operations in the region.

There, Vasily witnessed how Moscow-driven industrial development threatened the traditions of the indigenous populations by severing their herding routes and damaging the environment. From the boat that took his team up the Yenisei River, Vasily peered into the village of Karaul—60 percent of which is inhabited by impoverished Nenets—where “the wood on every house was rotting.”

“I heard stories from locals that every household had at least one family member who was either killed in an altercation or hanged himself, and that police were too scared even to enter the village,” he said.

A regional television channel recently reported how village locals still have no central water and must lug their supplies from the Yenisei River, which is likely contaminated.

“The level of decline and horror you witness in a place like that is eye-opening, and then you realize there are many more places like that across Russia and the country is f**ked,” he said.

Meanwhile, the heads of the institute would “pocket chunks of the budgets” allocated for expeditions, Vasily added.

“They would show up to work in Lamborghinis, but we’d have one shovel per five people for the dig.”

The rampant corruption was beginning to grate.

“The Academy of Sciences is controlled not by scientists but businessmen who just siphon off money all day,” he told me.

Political disillusionment

In 2015, Vyacheslav Ivanets, a 46-year-old lawyer from Russia’s eastern Irkutsk region, experienced profound disillusionment with the increasingly undemocratic election system when the authorities barred him from seeking reelection as a municipal councilman.

After obtaining his law degree in 1999, Vyacheslav worked as a corporate lawyer helping entrepreneurs fight against corruption-riddled state institutions. But in 2010, he turned to politics, first as a member of voting commissions and eventually as a municipal councilman in Angarsk—a suburb of Irkutsk with a population of about half a million—representing various local opposition parties.

Over the years, he garnered local fame and support for the various grassroots initiatives he spearheaded—from addressing ecological crises to improving public spaces. In 2015, officials claimed there was a discrepancy in his documents that supposedly disqualified him from ever running again. He believes his popularity and efficacy were the real reason the authorities barred him from seeking reelection.

“This was all ludicrous,” he said, “it really depressed me.”

During our hour-long telephone conversation, he referred to this moment on several occasions, characterizing it as one of the lowest of his life. He was calling from the Georgian seaside resort town of Batumi, where he was vacationing with his mother who flew to visit him from Russia.

The deep sadness in his tone made clear that Vyacheslav was still processing how the injustice affected him. Russia’s major opposition movement—primarily operating in Moscow and St. Petersburg—was well aware it was combatting an authoritarian regime. But for Vyacheslav, the tangible difference he was making on his region appears to have convinced him it was still possible to change the system from within.

It made his forced removal from the ballot all the more difficult to process. “Evidently I still haven’t found closure on this,” he told me.

Frustrated by the experience, Vyacheslav decided to direct his skills toward another cause and began offering legal services to victims of political repression—from regional journalists to activists working for the opposition leader Aleksei Navalny. Despite the growing repression surrounding him and his clients, he was still able to score victories in court, sometimes shielding activists from unlawful fines and arrests or protecting local newspapers from closure.

Yet his commitment to justice once again put him on the authorities’ radar, making it dangerous for him to remain in Russia, particularly after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

‘I shut the door’

A month into the campaign, Vasily was digging up 19th-century champagne bottles that were once distributed by the now-defunct imperial-era Badaevsky Brewery—near a newly built skyscraper complex called Moscow-City. Wiping sweat from his brow, he looked up at one of the skyscrapers and muttered to himself: “This will be the first thing [the Ukrainians] will strike.”

A year later, a drone purportedly launched by the Ukrainian Armed Forces smashed into the windows of one of the office towers.

On May 11, two days after Russia’s annual Victory Day parade, Vasily fled to Armenia. He didn’t leave because he was afraid, he said, but because of the feelings of revulsion he had begun to harbor toward his compatriots who continued to ignore the war.

“It felt disgusting to look at those as**oles sitting around eating ice cream after the Bucha massacre had just happened,” he said, referring to compelling evidence of systematic war crimes committed by Russian forces during the occupation of the Kyiv region town.

Vasily’s stepfather is Ukrainian, and because of his last name, Vasily said, his coworkers would call him a “Banderite,”––a Russian propagandistic slur for Ukrainians derived from the name of the World War II-era nationalist Stepan Bandera.

Eventually, his boss, “a highly educated and respected Russian archeologist,” forbade discussion of the war at the workplace altogether. Soon, however, he began to share online conspiracies about Ukraine infecting geese with Covid-19 and releasing them into Russia.

“When I left Russia, I sent [my boss] a message saying: ‘Hey why don’t you and your friends grab rifles and go fight in Ukraine?’” Vasily told me. “I shut the door on that job.”

“I couldn’t come to terms with how people were becoming increasingly fascist,” he explained. “I felt like I was a German fleeing the country in the 1930s.”

In Armenia, Vasily found free lodging at a shelter opened by Kovcheg, a civil-society organization funded by the exiled Russian former oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky that aids anti-war émigrés. Soon, he found work washing dishes at a restaurant.

Vyacheslav, the Irkutsk lawyer, experienced similar disillusionment in the wake of the invasion. Not with his colleagues but his closest friend. During a conversation one evening just after Russia launched its offensive, they seemed to agree on pretty much everything except for one point his friend made.

“Well, now that it’s happened, although it was a mistake, I guess we have to go all the way to the end,” his friend told him about the war.

“Initially, I had felt relief that we were on the same page,” Vyacheslav said. “Then, after he said that, I wanted to smack my head against the wall. His logic felt completely beyond the pale.”

Shortly after the invasion, Vyacheslav made a number of public comments opposing the war. That, coupled with his work defending regional coordinators of Navalny’s campaign—which the Kremlin had deemed extremist—made him feel unsafe.

By April 2022, he had made his way to Georgia. Friends back home who had contacts in the Irkutsk regional administration relayed to him that he had made the right decision, as he was very much on the authorities’ radar.

Even after the invasion, lawyers were still for the most part exempt from the kind of draconian punishments activists and journalists were facing. In October, however, the Kremlin shattered any illusion of safety by arresting two of Navalny’s lawyers, hammering home Vyacheslav’s concerns about his own safety.

“I always knew that my immunity had a certain limit, and every time I would enter a detention center [to visit a client], I would experience fear,” he said.

Once prison guards threatened him in a jail where one of his clients, a political prisoner, was being held, accusing him of disclosing “sensitive information.”

“It’s a chilling effect,” Vyacheslav said. Despite a mass exodus of human rights lawyers, some remain. But working in Russia is very hard, he added. “The more they see their colleagues being arrested, the more they question their career paths.”

In Vlada and Sergei’s case, family commitments kept them in St. Petersburg over a year after the assault on Ukraine. Vlada initially participated in protests and posted anti-war stickers around the city. But she soon realized new laws punishing Russians for “discrediting the armed forces” could put her in danger.

They have a son, who, for reasons they chose not to disclose, must remain in Russia. Tbilisi’s proximity to Russia made it an ideal destination, from where they have the option of periodically returning to see him.

Vlada’s 31-year-old son from her first marriage arrived in Tbilisi about a year ago and lives just two blocks away from her. Her daughter, also from her first marriage, is now in the city too, having arrived from Israel immediately after Hamas’s attack on October 7. Vlada’s mother was also visiting from Russia when I met them.

But not many from their social circle in St. Petersburg have made the jump into exile.

“Over the last few years, many of our friends began to really make money and could afford good apartments. But we always lived a sort of hippy lifestyle,” Vlada quipped.

Their decision to leave, Sergei added, was motivated by daily feelings of “shame and disgust” they felt toward everything happening around them.

“And we don’t just feel this in regard to Putin,” he said. “It was the general daily passivity those around us were exhibiting.”

A few weeks later in Yerevan, I met a young man who continues to live in St. Petersburg and echoed a similar sentiment. He works in shipping logistics at a moment when much of Russia’s economy has been redirected to supporting the country’s military spending. He was in the Armenian capital for a layover flight to Rome, and admitted his trip may have been one of his last to Europe because his EU-wide Schengen visa was due to expire. “If they close the doors to Europe, we’ll go elsewhere– like Central Asia,” he said. “I’ve always found the region interesting, imagine how much investment potential it has to offer.”

Work in Tbilisi

The growing Russian émigré community in Tbilisi was another major attraction for Sergei and Vlada, as it meant they could find work in familiar circles.

Sergei continues to teach hard sciences at Projector—an experimental Russian-language school founded after the invasion by Dmitry Zitzer, a well-known educational entrepreneur from St. Petersburg. Zitzer also keeps a pool of online pupils from Russia, whom he coaches for university and graduate school entrance exams. Even at 73, he is full of energy and plans to travel to Chile soon as part of a tour of the Paranal Observatory.

Vlada’s brother and friends from St. Petersburg’s pedagogical circles opened a Russian-language school in Tbilisi where she was hired to teach. The students are exclusively Russian-speaking children who moved with their parents to Georgia after the invasion.

The school also provides Georgian-language lessons for students. Critics have raised concerns that Russian communities in Tbilisi live in complete segregation from locals and that establishments such as Russian-language schools only contribute to such divisions.

However, anti-Russian sentiments exhibited by some Georgians, already prevalent long before the conflict in Ukraine, makes prospects for real integration look dim, at least for now.

Such feelings are most commonly conveyed through graffiti around the city that sends recent émigrés a clear message: You are not welcome.

But Vlada and Sergei brushed off any concerns.

“I’d rather see ‘F**k Russia’ scribbled on the walls around me than a Z,” Vlada said about the pro-war Latin Z symbol that is now seen everywhere in Russia.

“So far, everyone here has been friendly—and besides, perhaps Georgia will not be a final destination for us,” Vlada said. “If we have to move elsewhere, we will.”

Vasily, too, seems to take his emigration in stride. He moved to Georgia after nine months in neighboring Armenia, convinced that he could earn more here.

In addition to cleaning the homes of younger Russian émigrés, he washes dishes at night at a jazz club opened by musicians from St. Petersburg. Younger Russian émigrés “sit here on anti-depressants, thinking day in day out how they’re going to continue their jobs as photographers or whatnot,” he said of his clients. “They just need to get up off their asses and find work, any work!”

He discovered his two gigs through a Russian-émigré-oriented employment channel on Telegram called Tbilisi Jobs, where many skilled and unskilled jobs from construction work to electrician positions are listed. The majority of those who respond, Vasily said, are above the age of 35.

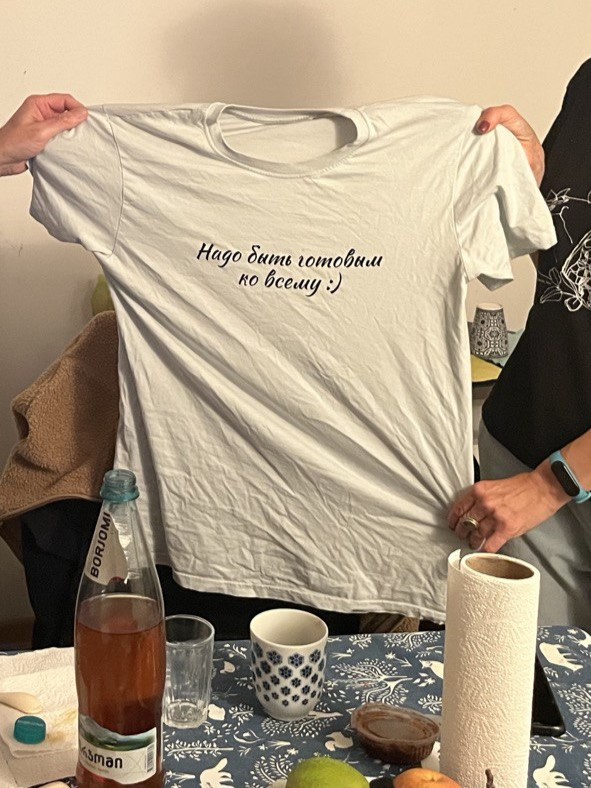

His plans, he said, are “to buy oil, canvases and paintbrushes—work less and paint more.”

A return to Russia is not on the horizon, however. “I can’t imagine my life in there,” he said. “It is too vast of a country, everyone who inhabits the country feels lost, like in space. It is a space that is incomprehensible to the human mind.”

As for Vyacheslav, he is still not entirely convinced his departure from Russia was the right choice. Toward the end of our conversation, which began to feel like observing a therapy session, he repeatedly mulled hypotheticals about what could have been if he had remained.

In Tbilisi, he quickly found work at a local law firm where he offers legal consultations to Russian-speaking entrepreneurs, including Belarusians and Ukrainians, who are registering businesses. He also continues helping activists in Russia on the side, referring their cases to the European Court of Human Rights, an activity on which he chose not to elaborate because of safety concerns.

While his clients in Georgia bring him a steady income, starting from scratch in a new country with a different legal system was no easy task, he said.

“Imagine losing all the clientele and reputation you had built up for years,” he told me. “You have to fight for your place here, and I am lucky to still be at an age where I have the strength for it. If I were 10 years older, I wouldn’t have risked it.”

‘Floating around with eyes closed’

When I asked if he would ever return to Russia, he told me that possibility was “simply not in the cards,” something he found psychologically difficult to come to terms with. His wife and two daughters remain in the country, a topic about which he chose not to speak.

“It was fine at first when I left but then something strange happened,” he said, as his voice, tinged with sadness and regret, trailed off.

“People still live there… and live fine,” he added. “Like those who are working in the military-industrial complex or the people in charge of sprucing up our cities ahead of the presidential election. Their lives have even improved. You can live in Moscow and ignore the war—don’t listen to the news, and there is no war!”

Vyacheslav proceeded to characterize the attitude of Russians back home toward émigrés.

“Let them leave! More jobs for us. More bread! We’ll be fine without them.”

But he believes such reasoning may be short-lived. The long-term effects of the war, he said, are yet to be felt.

“Things could change once all the handicapped veterans return from the front,” he said. “But for now, the Titanic is sturdier than ever because all of its passengers are united behind a single figure and continue floating on with their eyes closed.”

Top photo: Older Russian emigres enjoying the holiday season