BANGDONG, China — Teacher Ma pours another steaming cup of tea and, from his kitchen table, watches a sea of clouds rise from the Lancang River below. Everything is zen. Everything except for the boxes in the corner. After two years living in this remote village in the country’s southwest, he is moving back home and now his voice trembles: “They call me a Bangdong person,” he says of his neighbors. “They say we’re family.” His eyes glisten as he sits in silence for a moment. “Of course, they know me only as Teacher Ma. No one knows my name is Chitwood.”

I came here to write. After a decade working in China’s megacities, I wanted to learn about rural life for its almost 550 million residents and how it is changing with the country’s development. So I fixed up an old log-framed house with rammed-earth walls and moved in. And here I became Teacher Ma, a foreigner who speaks only Mandarin, asks too many questions and laughs easily, whether he gets the joke or not. Sometimes he is the joke.

I am at peace with my alter ego. Teacher Ma plays cards with the men, who try to get him drunk on corn liquor, and he gossips with the women, who try to fatten him up for their single nieces in nearby villages. He is well liked but utterly helpless. He can’t read the weather in the sky or the seasons in the land. His hands are baby soft. And he lacks the most basic sense of how to kill a chicken or turn out the intestines of a pig.

Now during my last week in the village, I reflect on Teacher Ma’s two years here. He has begun to understand rural perspectives on the United States and the Chinese Communist Party, on the trade war and protests in Hong Kong. He has witnessed rural development and poverty alleviation firsthand. He has even distilled batches of corn liquor and become an accidental expert in tea. But, most important, Teacher Ma has learned about himself. He wants to talk about China, of course, but the conversation that follows—his most in-depth and introspective interview yet—is more about Chitwood than China. He opens up about electrofishing and being the stupidest spy and shares his thoughts on re-becoming Matthew Chitwood.

Chitwood: This week you’re leaving after two years calling Bangdong home. What’s on your mind?

Teacher Ma: I’m thinking about the friends I’m leaving behind. The kind of friends who show up unannounced and keep you from getting any work done. The kind who insist you stay for dinner and even give you the chicken head because it’s their favorite. The kind who drive you to the hospital when you almost saw off your finger, or who sit with you in silence when your Grandma across the ocean passes away. Where did the time go? Why didn’t I show up unannounced more often and eat more chicken heads? Are there things I left unasked? Or unsaid? When will I see them again? That’s the pain and privilege of loving people in more than one place. They will always hold part of your heart elsewhere, which means you’ll never be completely at home anywhere.

What is it like making friends in a rural Chinese village? What did they think of you?

It was hard for them to make sense of me at first. They thought I export tea or teach as a volunteer. Then they were puzzled by how I called sitting inside with my laptop “work.” When you sweat over the earth and it gets under your fingernails, you define work differently than today’s digital nomads. Then some wondered if I was a spy. Why would a spy go deep cover in Bangdong? I’m not sure, but there is an undeniable similarity between the letters in “ICWA” and “CIA.” The mayor, who became one of my closest friends, asked me outright: “Are you a spy?”

“No,” I answered but wouldn’t James Bond say the same? I asked the mayor what he thought.

“I don’t think so,” he answered. “Everyone thinks you’re a spy, so if you are, you must be the stupidest spy.”

The community is small so it’s always getting together: weddings, funerals, work days, line dancing at the Communist Party Activity Center. I was constantly invited for meals (It’s just another pair of chopsticks!), or on bee-hunting expeditions (Larvae are high in protein!). What an honor to be welcomed into that. But depth of friendship formed as it normally does—a function of shared experience, conversation and time—so it didn’t happen overnight. Thankfully, my neighbors have a surplus of time once the sun goes down over their fields, so we would sit with a kettle of tea and sunflower seeds under a million stars and my asking too many questions. The guys who did that with me became my closest friends and are also the reason why I’ll never be completely whole in any one place again.

The US-China relationship has shifted dramatically during your time here. Did that affect your friendships or your research?

Shift is an understatement. They’re calling it “decoupling,” which is foreign policy speak for divorce. The month after I arrived, Trump made his first announcement about tariffs. Meanwhile, a tech war ramped up against ZTE and Huawei, Huawei’s CFO was detained in Canada, China started detaining Canadians and the United States arrested several spies for China. Meanwhile, tighter regulations for international NGOs and religious activities spurred a mass exodus of foreigners, internment camps in Xinjiang were exposed, protests in Hong Kong broke out and China boycotted the NBA. So, yes, there has been a shift. I recall one Chinese academic getting triggered when I used the phrase “stealing intellectual property.” She preferred the term “copycatting.” But overall, personal interactions have remained friendly. That is partly because there’s a sense in China that those are issues between our governments and far removed from us normal people. And also because I knew I wasn’t going to change anyone’s mind. But I did want to learn others’ perspectives, so I tried to ask good questions and listen well. In rare instances, I would come across people who also wanted to listen and learn new perspectives; those were good conversations.

Were you ever worried about your own safety?

Thankfully, I have a clear conscience. The Communist Party’s least favorite foreigners are spies and missionaries—and I’m neither. It’s twisted, I know, but I’m almost glad they’re surveilling me—and I hope they’re doing a good job of it—so they know what I’m not doing. Still, a few days ago, I did get a call from the local propaganda bureau inviting me in to “drink tea,” a widely known euphemism for getting a talking to from the Party. These folks are not very high up—their activities include making cartoons to communicate Party messaging to illiterate farmers—so I wasn’t fearful, but I didn’t know what to expect. It turns out they actually wanted to drink tea. (I do live in a tea village.) What do you think about our tea? How would you address our environmental challenges? What about the poverty elimination campaign? They asked good questions—How can we do better?—and I appreciated that they valued my perspectives. They even wrote up a nice piece of, well, propaganda, that quotes me as saying “The Communist Party is good.” What I said was, “The Communist Party has done a good job improving the economic livelihoods of people in rural Yunnan.” Oddly, my comments on the trade war and Hong Kong didn’t make it into their piece.

You mentioned the poverty elimination campaign. Tell me more about that—is it even possible to eliminate poverty?

China has had poor people for a long time. And it’s long made efforts to address that with trickle-down economics, infrastructure development projects and social programs. But General Secretary Xi Jinping is the first politician to make it a SMART goal—specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, time-bound. In 2013, he proposed China end abject rural poverty by 2020, then the State Council made it an official policy goal in 2015. Since then, the Party has thrown all its resources at the problem: money, people, know-how. In 2016, the first year after the effort became official policy, central and provincial governments almost doubled spending on poverty elimination, an increase of about $6 billion—more than spending increases of the previous eight years combined. And it’s only gone up since.

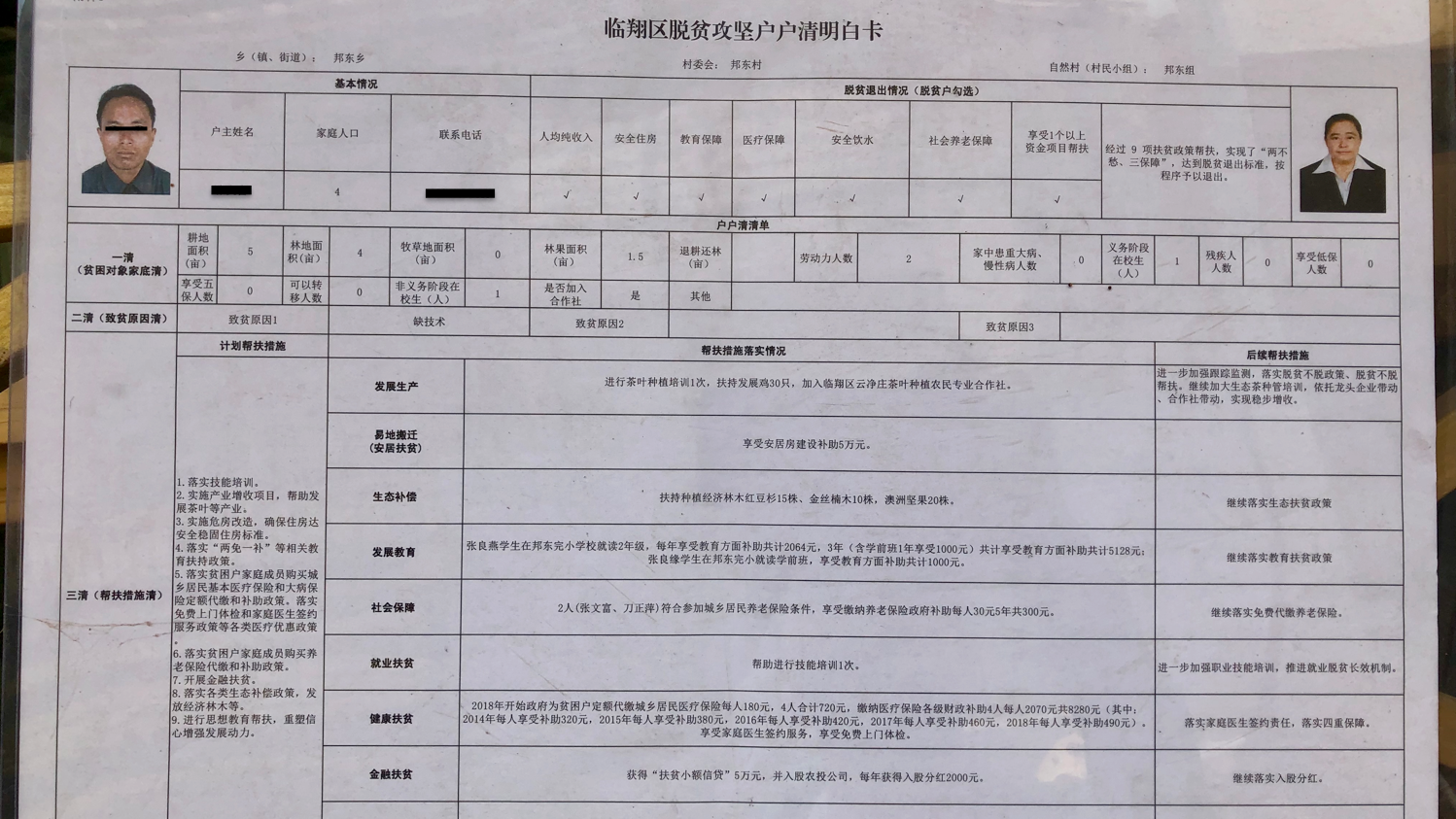

Each impoverished household across the country has been surveyed—family size, land size, livestock and crops, annual income—and entered into the government’s big data system, then provided something of a ten-point plan to get them out of poverty and paired with an individual Party member responsible for making that happen. According to official statistics, 98 million people were impoverished in 2012. By the end of 2019, that should be reduced to 7 million. That is an incredible feat. I will say that the abject poverty bar is low—roughly $500 annual income per person, plus basic education, healthcare and housing. There are also very legitimate concerns around the accuracy of official stats, corruption and sustainability of the effort. After the goal is achieved and officials get their promotions, will these people just fall back into poverty? But when you’re living on under $2 a day, these anti-poverty policies are high-impact. In Bangdong, families received about $7,000 to build new houses, schooling is free and about 95 percent of costs for medical treatment is now covered by national health insurance. So the mountains had cut these people off from economic opportunity for their entire lives, and now for the first time they have new homes and roads, and access to education and healthcare. They are materially better off than ever before. Is it any wonder they love Xi Jinping, who is on every poverty elimination billboard in the countryside?

A case file hangs on the front door of each impoverished household with personal details such as land size, annual income and a bullet point plan to get the inhabitants out of poverty

Are you saying the Chinese Communist Party is good?

No, that’s what the local propaganda bureau says I say. Don’t you go misquoting me too, please. I say that the Party has done a good job improving the economic livelihoods of people in rural Yunnan, including my friends and neighbors in Bangdong. I also say that it prioritizes the Party’s power over the people’s interests and uses “rule by law” as an enforcement mechanism. When that is taken to extremes, you get gross violations like the internment camps in Xinjiang. Then project that onto the global stage and China’s rising power becomes disconcerting. Yet, we often vilify the Party in a simplistic way, which isn’t helpful, and declare ourselves righteous, which isn’t accurate. Then our only explanation for how 1.5 billion people can tolerate Party rule and infringement of their basic human rights is that they are brainwashed by state propaganda. Well, it’s a bit more nuanced than that.

The Party has done a phenomenal job at maneuvering economic levers to grow the economy and improve livelihoods all the while maintaining social stability and staying in power. One of the things that surprised me was that so many Chinese people are proud of what their country has achieved and are satisfied with the Communist Party’s accomplishments. And that many of those same people are also frustrated at limitations on their freedoms and have concerns about stronger Party control since Xi came to power. Author Ian Johnson captured the nuance well in a New York Times piece about the Communist Party’s 70th birthday in October. The people waving red flags were not props; they looked just as earnest in their love of country as Americans do when they stand, hand on heart, for the national anthem. He wrote: “Realizing that some of these emotions are genuine is important because we can’t understand China if we think the party only rules through the authoritarian methods that reporters understandably focus on.”

What else did you learn that surprised you?

Life in the countryside is vulnerable. In the US, we both fear and plan for the unknown: health insurance, car insurance and life insurance; retirement plans and contingency plans. We think we can control, or at least mitigate, the Fates. But my friends in the countryside have no such illusions. Their lives depend on the weather, hard work and some luck. There is no 9-to-5, no stable income, no weekends. There are no protective guards on their saw blades, no safety goggles and no steel-toed boots. Bad things happen. And often. One week, I came across a woman who had fallen down an embankment while picking tea and was lying bloodied in a ditch. Later that same day, my friend Old Thief slashed his forearm on broken glass and had to be rushed to the hospital three hours away. Everyone knows somebody who has plunged off the mountain roads to his or her death, or has a foot-long scar from a knife fight or a power tool accident, or whose stomach lining has been eaten away by corn liquor. That’s why access to healthcare is such a game changer for them. Peace of mind has been a luxury few in Bangdong could afford.

Did you ever have a moment of crisis when you thought “What am I doing here?”

Early on, I remember feeling particularly lonely, so I tried to FaceTime my parents and my brother’s family. Both calls kept getting cut off due to “unstable connection.” I was in rural China, in the middle of nowhere, but ironically the issue was on the Idaho side. The call was so dissatisfying that I finally just gave up; we couldn’t even say a proper goodbye. So I was feeling lonely, it was a rough day, and—please don’t put this in the article—but there may have been tears. So I asked myself: Why am I even here? Away from the people I care most about? For two years? What’s the point? But then you go through the mental exercise of reminding yourself why you’re here: This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. I miss my family and there is purpose in my work. You knew this would be hard and worth it. Then you pick yourself up, go hunt some beehives to make yourself feel better, and press on.

What is one of your favorite memories from your time in the village?

There were so many experiences unlike anything I’d ever experienced. Circle dancing all night to reed pipe music around a wedding bonfire. Watching the World Cup with Party officials at the police station. Rats and bats in my house. Digging a neighbor’s grave and eating a neighbor’s dog. Hunting grasshoppers for a late-night wok-fried snack.

One of my favorite memories was Take-the-Foreigner-to-Work Day. I shadowed my friend Yun Chuan who was building a tea-drying greenhouse for a neighbor. I was aghast as he and his work buddies buzz sawed steel pipes and welded crossbeams in open-toed sandals. One grimaced and howled in laughter as the arc welder dripped molten metal on his feet. The buzz saw gnawed through steel and spat out sparks on another’s toes. Yun Chuan fashioned a welding mask from an old pair of women’s sunglasses and a box of beer. Our hosts killed a chicken for lunch and then, after we emptied a case of beer, naptime. The day was a constant troubleshoot as tools broke and supplies ran out, until they decided to quit early. So we went fishing. And by “fishing” I mean wading upstream with an electrified rod and net, zapping small fish and an occasional water snake. We played cards at his buddy’s house until his mom called us to a fish feast under the stars where corn liquor continued to eat through their stomach linings. It was a typical day in Bangdong.

You also traveled extensively outside Bangdong, visiting other villages and even taking a 2,000-mile motorcycle trip around Yunnan. What else did you learn along the way?

Yunnan is so diverse in its people, plants and animals, and geography. I was fortunate to celebrate Mother Drum Festival, a traditional celebration of the ethnic Wa people that has turned into a commercialized city-wide mud fight. I spent Christmas with the remote and predominantly Protestant Lisu people. I witnessed encroaching development in Yubeng, a Tibetan pilgrimage site and trekking paradise known for having no road access—until the local government built the first road a year ago. I visited rice paddies, tea terraces, coffee plantations, pomegranate orchards and vineyards, talking with everyone along the way. I was overwhelmed by people’s hospitality, their willingness to open their homes and hearts to me and let me peer into their ordinary lives, which I found extraordinary. What an honor.

It seemed each conversation spoke to the rising tension between development and the preservation of Yunnan’s diversity. I spoke with Lisu and Tibetans, Mosuo and Dai who are eager for roads and economic opportunities and tourist dollars. But many communities don’t have the political or economic wherewithal to ensure their own healthy development in the face of competing interests with government officials or development companies, neither of which give much credence to self-determination. Yet, like I said, people are materially better off than ever before. So how do we critique the effects of development and the role of the Party? It’s all very nuanced. We like black and white, clear-cut, right and wrong. And it’s easy to make curt judgments from afar. But life is messier than that. China author Evan Osnos compares journalism to black and white photography where you have to capture the right balance of light and dark. As I heard more people’s perspectives, I became better at understanding the nuance and trying to embrace the ambiguity.

Experiences like these inevitably shape us as well. What did you learn about yourself in the process?

As a single 35 year old, I went into my two years in a rural Chinese village expecting it to be relationally challenging. More than just not having a girlfriend, I mean not having real community, not being deeply known. Even as friendships developed, it was amazing to experience and learn to embrace loneliness. We tend to avoid loneliness at all costs. The omnipresence of social media in our lives reveals our inner longing for connection, affirmation and significance—and distracts us from the pangs of loneliness that we all feel at times, single and married alike, more often than we’d like to admit.

The author Henri Nouwen put it something like this—that when we have no friend to visit or project to finish or television to watch and are left all alone, we are so afraid of our basic human aloneness that we get busy again to convince ourselves that everything is fine. He wrote that even before we invited Facebook into our hearts. How much more, then, is that true with the advent of smart phones?

In Bangdong, I’ve had friends to visit and books to read, but I’ve still felt very much alone. But Nouwen also compares loneliness to the Grand Canyon, a deep incision into our very being. If we peer into it rather than run from it, it becomes “an inexhaustible source of beauty and self-understanding.” I can think of no better environment than Bangdong—away from the efficiency of American life and the over-stimulation of China’s megacities—to be forced, or in retrospect, to be privileged to peer into this canyon. In the absence of social media, in the dearth of people who know me deeply, and in the silence of loneliness, I discovered two voices inside myself. One says things like, “You’re incompetent” and “Your writing is worthless.” Those things are easy to believe. But the stiller, smaller voice, the one that I have to slow down and quiet my heart to hear, it says kind things—things like, “You are capable.” “You bring joy.” “I do not regret you.” Sometimes those words are harder to believe. Some people might call that faith.

While I’m incredibly grateful to have learned about rural China, I am even more grateful for the unexpected and unparalleled opportunity to know myself. Thank you ICWA and Director Greg Feifer for granting me this journey.

What’s next for you? An exhaustive cereal aisle awaits on the other side of the ocean. Are you ready for the reverse culture shock?

In the near-term, I’m working on a book about development in rural China and then will be job-hunting—something I hope will allow me to work remotely from a certain small village in China.

In Bangdong, a market rotates through town every five days. Things are simple: I have a pork guy, a vegetable lady and a rat poison guy. But every time I return to the United States, the grocery stores amaze and overwhelm me. I wander the aisles for hours, paralyzed by choice. Cheetos are no longer just Cheetos. There are Original Cheetos and five other ways to stain my fingertips orange. I’m inevitably struck by the size of Americans, our daily dependence on cars and the fenced yards that divide us. Also, I’m not sure if I’m ready for constant connectivity. Twitter, Facebook, Instagram… everything is blocked in China. Some call it the Great Firewall. I call it freedom.