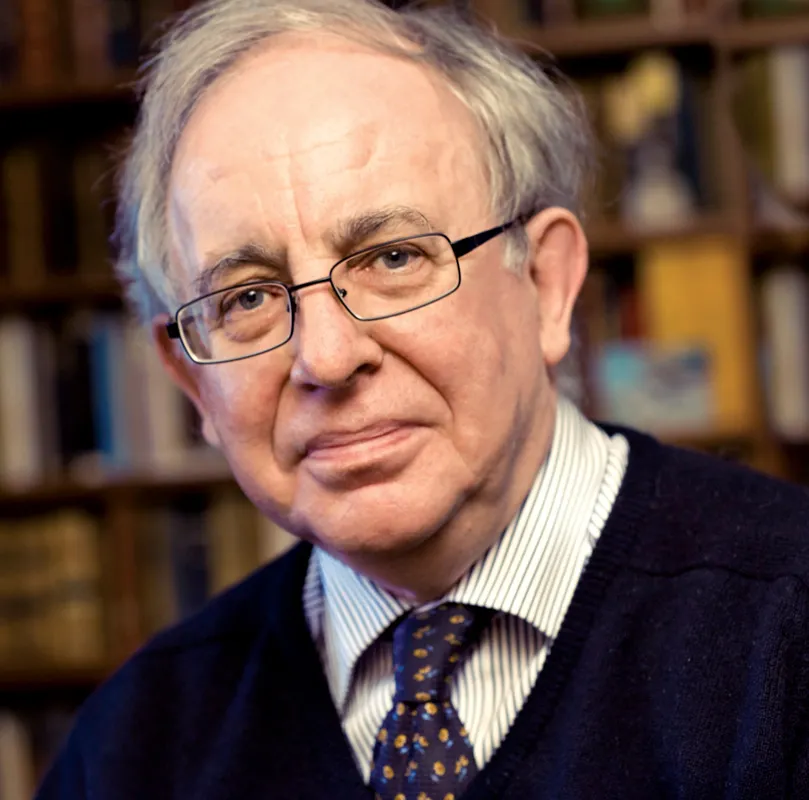

Oxford scholar, leading expert on Latin America, adviser to Colombian presidents and ICWA fellow (Colombia, 1964-1965) Malcolm Deas died at his home in North Oxford, England on July 29, 2023. He was 82.

When he arrived in Colombia for his fellowship as a young Oxford graduate, the country was “documented by only a handful of historians,” Richard Emblin wrote in The City Paper Bogota. “Deas’s research into the origins of conflict, the rise of institutions, the democratic model of Colombia, would not only benefit Oxford, but also shape the way Colombians understood themselves and their place in history.”

Among his observations was the Catholic Church’s control over society. Passing through a dusty provincial town during his fellowship, as he described in one dispatch for ICWA, he went to see the local bishop, “the only person for miles around who could change foreign money.”

He sat at his desk, behind telephones and typewriter, files and paper trays, the outward, progressive signs of the inward and colonial church. Behind him on the wall hung a heavily spiritualized portrait of himself, the intent eyes fixed on me softened by the painter and turned upwards to heaven, the burly frame made decently frail, the vigorous beard a saintly straggle. An awkward poor man stood in a corner twisting his hat in his hands, for the Bishop was dealing with dollars and bigamy at one and the same time.

“Yes, yes, and what is the rate today?” I gave him the official rate from the morning newspaper. “Ah, but I’m not a Bogota bank! The street, what are they giving in the street? This isn’t Bogota.”

He turned to the peasant: “It doesn’t matter what she did. You shouldn’t have done it all the same. It’s a grave sin. You should have known. There’s no excuse, I don’t want to hear excuses. Wait a minute.”

He named me a rate well below the official level, a rate that would have found no takers in the street. I only had cheques, and the street rate was for bills only. He assured me that his rate was very good, and that I was very lucky.

“Besides,” he said, “I have to send money to Rome.” He paused and looked at me apprehensively. “You are a catholic, aren’t you?”

Following his fellowship, Malcolm returned to Oxford, where his academic career spanned nearly 50 years. Appointed university lecturer in the government and politics of Latin America age 25 together with a fellowship at St Antony’s College, Oxford, he remained a fellow of the college until his retirement in 2008 and an emeritus fellow after. An original staff member of Oxford’s Latin American Centre, he served as director several times.

Malcolm’s pioneering work—focused on 19th and 20th-century Colombian history, and also Venezuela, Ecuador and other countries—“was highly esteemed in Colombia itself for his original contributions on a wide range of topics, including fiscal and agrarian history, the history of civil wars, elections and photography,” Roger Goodman wrote in a tribute on the St. Anthony’s College website. Malcolm was author of many essays and articles and several books including Intercambios violentos and Vida y opiniones de Mr William Wills.

“In appearance, Deas was the acme of a distracted Oxford don,” John Paul Rathbone wrote in the Financial Times. “He invariably wore a dark jacket, white shirt and black tie. He didn’t have a doctorate and his definitive history of Colombia, one of the greatest books never written, was the deliberate result of a choice to avoid ‘the ranks of last word historians.’ He spoke perfect Spanish with an appalling English accent that he could not, or preferred not to, change.”

Malcolm was an adviser to a number of officials, including the Colombian presidents Álvaro Uribe and César Gaviria, for whom he helped design policies to reduce the country’s notorious violence. His counsel “led directly to Colombia appointing civilians as defense ministers, an almost unprecedented move for the region,” Rathbone wrote.” He also “helped to shape the security policies that tamed the country’s drug cartels, end the western hemisphere’s oldest civil conflict, and saved thousands of lives.”

Malcolm also painted watercolors and curated photography exhibits. Among his many distinctions and honorary degrees, he was awarded Colombia’s highest honor, the Cruz de Boyacá, and an OBE by the British queen. He was given Colombian citizenship in 2008.

“He had an extraordinary range of intellectual interests as well as strong (and often heterodox) views on an even wider wide range of topics,” Goodman wrote, “always supported with a copious amount of historical, sociological, statistical data and often a wicked sense of humor.”

Malcolm was born in 1941 in the southern English village of Charminster in West Dorset, his mother was a homemaker and father an army officer.

Top photo: Bogota, Colombia, August 2017 (Pedro Szekely, Wikimedia Commons)