LISBON — I meet Ines and Milton at the headquarters of Crescer, a leading non-profit that serves people who use drugs in precarious situations, near the traditionally drug-riddled western neighborhood of Casal Ventoso. Ines is eating the biggest personal bowl of Jello I’ve ever seen: hearty sustenance before an evening out in the cold streets talking with people experiencing homelessness.

Ines and Milton are part of Crescer’s street outreach team focused on five Lisbon neighborhoods. In December, it came into contact with over 490 people—approximately a third of all reported street homeless in Lisbon—spanning 40 nationalities.

By serving those in very vulnerable situations where they are living, Ines and Milton are able to provide psychosocial support to those who would otherwise never receive it. It includes help making housing and health care referrals to migrant assistance programs and distribution of harm-reduction materials. Two more Crescer street outreach teams focus on providing drug use and addiction-related care, although their missions often overlap. They’ve agreed to let me join them for one of their night outings to understand the impact of their approach firsthand.

Founded in Lisbon in 2001 to help implement the government’s new drug reform initiatives, Crescer now boasts an impressive array of programs that serves around 2,000 people in vulnerable situations annually. They include housing first, employment re-integration services, a drop-in center, immigration assistance and street outreach teams. The wide breadth of services allows the organization to streamline referrals internally between programs. Its street outreach teams are one of only two such programs in the country, with the other in Porto.

Milton grew up in Lisbon to Cape Verdean parents and is a peer, meaning that at the ripe age of 29, he’s previously lived on the streets. He sports colorful new sneakers, short dreadlocks and a shy demeanor. Ines, 25, is more outgoing, she’s originally from Porto and misses the affability of her hometown. Glasses frame her face together with long brown hair that comes down past her shoulders. She has been on the job for nine months starting right out of university. Milton has been on the job a month after most recently working at an IKEA warehouse. They had hoped to bring donated socks with them. Socks are a big hit with people who are homeless, particularly as the weather has been getting cold, but the stock had run out.

After introductions, we drive to the bustling Cais do Sodre neighborhood, home to the ferry and train stations on Lisbon’s southern tip. It’s the week between Christmas and New Year’s, and streets are adorned with festive lights. We are dressed like we would be on any evening out in Lisbon, but the Crescer-branded vests and thick-soled boots we all change into distinguish us and our mission.

We are here to meet Motta, who, in his 50s or 60s, is the respected elder of the local encampment near the ferry terminal where passengers commute across the Tagus River. Motta observes our arrival through a slit in his green tent’s zipper with tired, kind eyes. He has a greying beard and dirt fills the creases of his lined face. On the metal fencing behind his tent is spray-painted “AIDS is the devil” in Portuguese. Around us, a group of men lazily loiters with beer cans.

One of the young men helps park an arriving car for a not-so-voluntary fee, a time-honored hustle and easy money for those living on the street. His name is Rui, at over 6 feet tall, he looks older than his 22 years. He likes to crack jokes and tries to flirt with Ines, who pays little heed because she is here on a mission.

Motta must be ready at 9:30 a.m. tomorrow, Ines insists. No, she can’t tell him why. It’s a surprise!

Motta doesn’t seem thrilled about waking up early. But tomorrow his life will change dramatically because Crescer’s housing-first team will come to offer him his very own apartment. He’s been on the street for 15 to 20 years, perhaps more. He rarely accepts help, but has always requested a home and tomorrow, although he does not know it yet, will be his lucky day.

As Ines talks, Motta sucks on an empty inhaler, making a desperate hollow sound. She asks if he needs a new one and writes a note to herself to bring one next time. He acknowledges his several health problems. Ines’s teammates have offered multiple times to drive him to the hospital or a doctor, but every time he mutters “Next week, I’m too tired today.” His best friend who had been living on the streets with him for years recently died while receiving care at a hospital. Before, he was afraid of doctors, now he’s terrified of them.

Motta finally gives in to the bubbly young woman in front of his tent who comes to see him every week. Tomorrow, he’ll be ready at 9:30 for whatever it is she thinks is so important. Her mission accomplished, Ines, Milton and I bump fists with the young men and get back in the car. They seem to mostly be Portuguese like Rui and Motta, although in the fragile light of the streetlamp it’s hard to tell if one or two might be South Asian or South American.

At no point do I feel threatened. Crescer is well-known in these parts and folks usually enjoy the opportunity to chat. Ines is quite popular with her long brown hair while Milton, still new to the job, observes and learns.

For the next stop, we drive up to the Jardim da Cerca da Graça, a beautiful park overlooking the eastern side of the city and river with the historic Castelo de São Jorge lit up in turquoise blue on a nearby hill. It boasts a kiosk selling Portuguese pastries during the day and a children’s playground. We park on a nearby inclined street and walk through the iron gates.

Only a few moments later, we hear rustling behind the closed kiosk and turn our heads sharply to the right. As Milton shines his light, Ines calls out “Crescer, outreach team!” We see a women squatting on the pavement with tinfoil laid out in front of her. The woman, I’ll call her Maria, walks over. Ines knows her from previous visits. Maria is Ukrainian, although it’s unclear if she’s a migrant from an earlier era or a recent war refugee as she speaks decent Portuguese.

Maria asks if she can call her daughter who lives in Portugal, which she does. Ines talks with the daughter, establishing contact and offering to act as a conduit with her mother when necessary. Maria then asks for the phone and talks to the daughter briefly. It’s clear she is happy to be able to chat with her, it’s the holidays after all. It’s unclear the last time they’d seen or talked to one other.

When the call ends, Maria complains about the cold. The temperature has dropped to about 40-45 degrees Fahrenheit (5 degrees Celsius). Bare skin protrudes from her too-short pants. She wears only a light sweater and flimsy shoes. Meanwhile, I am dressed in three layers, a hat, warm socks and boots. She asks for some aluminum foil. After giving her a long sheet, Ines asks if she wants anything else. Nothing. We walk on.

Aluminum foil is used to heat and smoke crack cocaine and sometimes heroin. Back before street teams and harm reduction organizations gave it out free, it was a lucrative business to sell squares of aluminum foil, with young hustlers calling out “Plata, plata!” like hawkers in a town square.

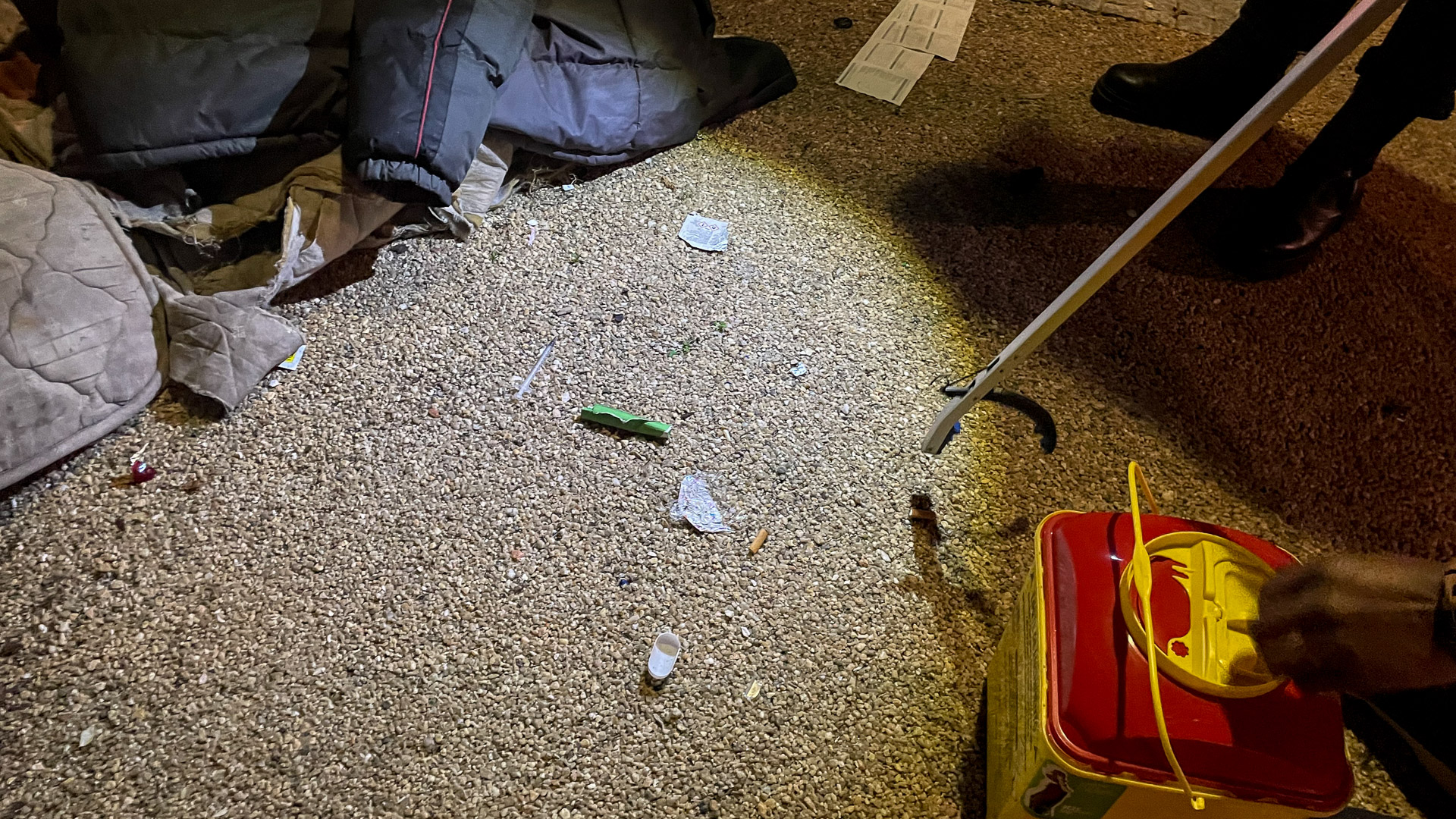

At the bottom of the park, we find the kids’ playground. It’s littered with needle wrappers and other drug paraphernalia. Ines and Milton scour for needles but find none. The other teams must have been here earlier in the week and picked them up. Ines explains that some people climb the kids’ fortress to the top of the slide to smoke or inject drugs because it protects them from view and the weather. The playground is covered in woodchips, a dangerous choice because wrappers and needles become hidden underneath them.

Further on, we pass a climbing dome similarly littered with wrappers. I wonder if any kids actually benefit from this well-intentioned and relatively new playground. While there are no needles here today, it only takes one bad needle to change a life forever. I certainly wouldn’t let my nephew play here. I wonder if local neighborhood groups have tried to take the situation into their own hands. It seems like a nice residential neighborhood but in Lisbon, it’s hard to know because the city is generally covered with a thin layer of grime where dilapidated buildings flounder next to luxury apartment complexes.

Past the climbing dome, we see another tent. As Ines announces our presence, a woman in her 30s or early 40s with caramel skin and short, curly black hair pops her head out. Alexa, a pseudonym, is happy to see us and chats with Ines for a while about a crime novel she’s about to conclude. She loves to read and tries to finish a couple books a month. Alexa informs us about comings and goings in the park and any unusual activity she’s noticed. She doesn’t want anything, the friendly conversation was more than enough, so we move on.

Ines explains that Alexa and her partner have tried living in shelters but given the unappealing and many times unsafe conditions inside such establishments, they end up preferring to live on the street where they’ve been in contact with Crescer outreach workers for years.

A few steps further, we hear the garble of American reality TV cutting through the silent night. Tucked away in the dark of the playground, a man watches a show on his smartphone with the zipper of his tent open. The glare from the screen illuminates his scarf, beanie and bushy beard with a pale blue light. From afar, Ines asks in English if he needs anything. He replies in English that he has all he needs. Ines doesn’t know this man and Alexa warned that he might have a dog, so we’re careful to keep our distance and continue walking.

Further on, we come across a South Asian man sitting on a bench of the mirador overlooking Lisbon’s red tiled roofs sloping down toward the Tagus. It’s difficult to know if the man is simply enjoying the view of the city or planning to rough out the night. Lisbon has become a paradise lost for many Nepalese, Bangladeshi and Indian migrants. Tens of thousands have been lured to Portugal over the past decade by fixers with assurances of lucrative work and housing. The stories vary, but many flock to Lisbon for sanctuary after the embellished guarantees fail to materialize.

The middle-aged man sports a thin mustache. After timid introductions in English, he asks if we have some water and aluminum foil. We give him some foil. Two young South Asians in their 20s walk by and, seeing the Crescer vests, also ask us for aluminum foil.

In this new area with its dazzling view, we discover about a dozen syringes which Ines and Milton put into a bio-hazard box brought specifically for this purpose, using a litter-picker pincer. Like at the playground, we do not bother with the wrappers, there are too many.

The middle-aged South Asian man tells us there are many more needles up in the forested part of the park. We thank him for the information, but Ines explains to me privately that they or other team members will go there later, during the day. It wouldn’t be safe to enter those parts at night as people sleep up there and with only the light of our small flashlights, we wouldn’t want to put ourselves in a dangerous situation.

Instead, we walk the path up the highest point of the park that borders the forested area. At the top, we meet another South Asian in his 30s. He introduces himself as from Nepal, I’ll call him Sujan. He’s wary at first but has a quick smile and warms to us when Ines explains our mission. He hasn’t heard of Crescer’s outreach team before. He’s been living in Portugal for nine years, although seems to have become homeless only recently. Sujan says there are half-a-dozen or more who live in this small patch of greenery at the northern part of the park. He’s the only one home at the moment, which explains why it’s so quiet. It can get quite loud when everyone else is around, he complains.

Ines asks if he’d be interested in checking into Lisbon’s drop-in center, where he could take a shower, wash his clothes and eat a warm meal. He very much would but explains that he was turned away a few weeks ago because the staff weren’t convinced he was homeless. Ines assures him that now she has his name and date of birth, she will email the drop-in center tonight and he will be able to go in tomorrow.

What about renewing his residency paperwork, Sujan asks hopefully. He tried a few months ago but wasn’t able to get his documents together in time for the appointment he made. The center can help him with his immigration paperwork too, Ines reassures him.

“I’m so happy. Tonight I feel very lucky!” he exclaims with a huge grin on his face. We say farewell. As he turns away to go back to his cold tent, it warms my heart to know he will sleep sounder tonight knowing that within the next couple days, he’ll be able to enjoy the bare necessities of life on this Earth.

We walk back to the car, a good night’s work done. Ines and Milton drop me off at Cais do Sodre, where we’d started our journey. With 20 minutes to spare before my train to the nearby town of Cascais. I stop by the buzzing Time Out Market near the station. Inside is warm and the aromas of two dozen gourmet kitchens hard at work serving hungry tourists waft through the air.

The mood is joyful as families and friends dressed in the latest fashions gather around communal tables abuzz with merry conversation. Did I ever say that one must travel far to explore worlds apart? I was mistaken.

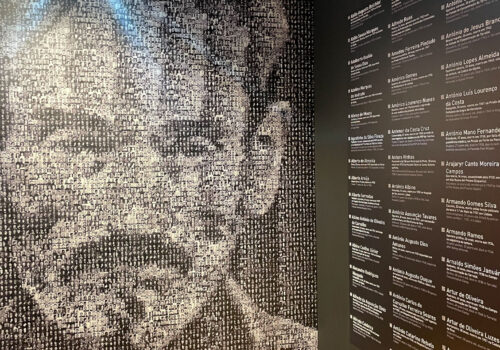

Top photo: Ines and Milton look for needles in the Jardim de Graça playground