CAIRO — On the morning of September 11, students from Greek community schools, their parents and teachers gathered in the courtyard of the Spetseropouleio building in the suburb of Heliopolis for the agiasmós, the holy blessing that marks the start of the school year throughout Greece. I arrived at the walled compound early to see children in white and navy-blue uniforms playing on a basketball court and greeting each other after the summer break.

The imposing if slightly faded Spetseropouleio shaded the courtyard from the harsh Egyptian sun. The desert sun and sand eat away at all of Cairo’s structures. Once an orphanage, the yellow building with its white columns, palatial entryway and peeling shutters now houses the Achillopouleios primary and Ampeteios secondary schools, as well as the Greek cultural center, a guesthouse, restaurant and athletic group. It reminded me of the equally massive Zografion Greek High School I’d visited in Istanbul at the start of my fellowship two years ago.

Both schools once served a much larger Greek population. In the 1920s, when the Greeks of Cairo exceeded 20,000, there were 12 schools with some 2,600 students. Today, the community numbers about 2,500, and the two remaining schools have fewer than 100 students in total.

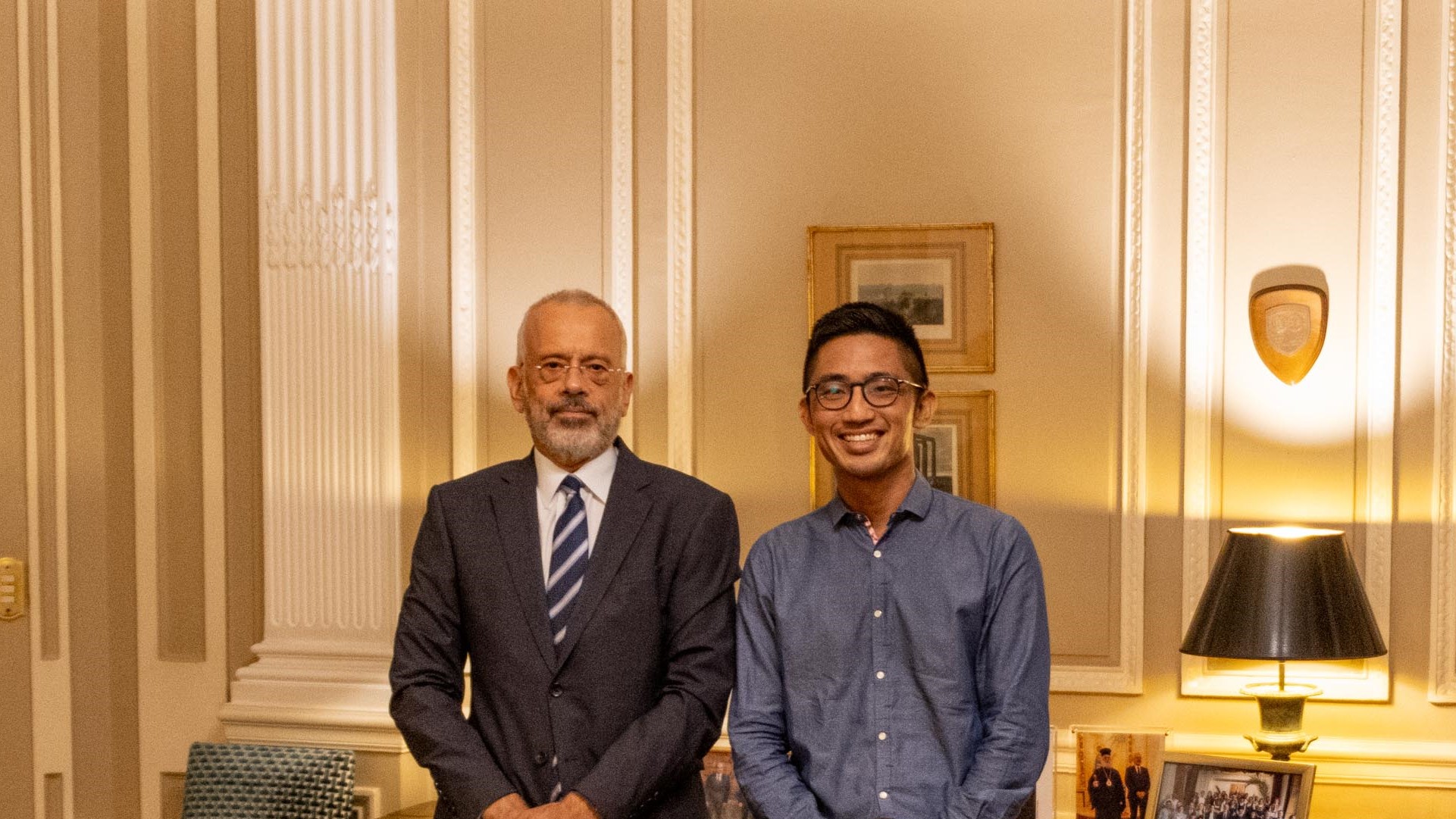

In the presence of the Greek and Cypriot ambassadors and other dignitaries, two students raised the Egyptian and Greek flags while the others sang the countries’ anthems with occasional aid from a nearby teacher. Christos Cavallis, president of the Cairo community, wished the students a fruitful school year, calling them the heart of the community. Then a priest sprinkled the building with holy water and blessed each child individually, tapping foreheads with a wet sprig of basil. Female instructors and mothers with uncovered heads recorded the proceedings. In total, I counted three women with headscarves, likely in mixed marriages with Greek men.

That first encounter with the Greeks of Egypt, or Egyptiótes, as they call themselves, granted me a glimpse into a close-knit diaspora community that, for over 200 years, has continuously adapted to changing conditions on the ground, maintaining ties with homelands on both sides of the Mediterranean Sea.

Greeks formed the largest, wealthiest and most diverse of the European communities in Egypt from the early 19th century until the 1960s, according to the historian Alexander Kitroeff. Among them was Constantine P. Cavafy, widely considered the most distinguished Greek poet of the 20th century, and prosperous families like the Benakis, Choremis, Salvagos and Rodochanakis who dominated Egypt’s cotton and tobacco industries.

Given the long history and former influence of Greeks in Egypt, I was surprised to find that Greece’s southern neighbor is often overlooked. On the island of Crete, my base for the past nine months, few locals saw their island as a border region, even though the ancient Minoans (3000 to 1100 BCE) traded with Egypt and decorated Egyptian palaces with their frescoes; even though a proposed power interconnector would deliver renewable energy from northern Africa to Europe via Egypt and Crete. My flight from Athens to Cairo lasted just under two hours, less time than it would take to reach most European capitals.

A Greek diplomat offered a possible explanation for this neglect, what she called “the existential crisis” within each Greek. “Because we strive to be more like the West, we disdain everything that connects us to the East,” she told me. “But the truth is, we have much more in common with the people here and in southern Europe than we do with northern Europeans.”

Indeed, my first impression of Cairo was of an exuberant, chaotic city similar in spirit to Athens, but with the volume and intensity dialed up. The dry desert air smelled of exhaust, and drivers leaned on their horns to communicate with the cars around them. There were no traffic signals, so crossing the street was like playing the video game Frogger. Walking downtown at night, I stuck close to locals, crossing when they crossed. Men sat outside alley cafes smoking shisha instead of drinking ouzo. Weaving through groups of women in hijabs, I sidestepped dripping air conditioners, books and toys laid out on blankets and a man on a corner selling sushi from a box.

The bustling capital is home to over 22 million people, more than double the entire population of Greece. Although the Egyptiótes account for just a fraction of that number, their legacy remains in the impressive schools, hospitals and churches they built and in the special relationship they claim to have developed with the Egyptian people. As diplomatic ties deepen between the two countries, I visited Greek institutions and met with Egyptiótes in Cairo and the historic Mediterranean port city of Alexandria to learn about the history of Hellenism in Egypt and discover how the community has managed to sustain itself. I found a dynamic, resourceful and well-organized Greek diaspora with compelling arguments for strengthening bilateral ties.

From ancient trade partners to modern allies

The Greeks and the Egyptians are descendants of two of the world’s oldest known civilizations, and archaeological evidence shows that they communicated extensively across the Mediterranean Sea. The connection between the ancient societies has long been used by Egyptiótes and the Greek state to assert a unique relationship with the Egyptian people.

After invading the Persian empire and defeating Darius III, Alexander the Great, king of Macedonia, marched south to take Egypt, which surrendered in 332 BCE without a fight. He founded the city of Alexandria on the Mediterranean coast, and it became an important center of science, arts and culture in the Hellenic world as well as the capital of Egypt for nearly a millennium until the Arab conquest of Egypt in 641 CE.

The Library of Alexandria was a beacon of knowledge and learning, and the city’s lighthouse was one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. Ptolemaic kings popularized the worship of Serapis, a deity who combined aspects of Greek and Egyptian gods, as a way of unifying its subjects. I visited temples dedicated to Serapis not only in Alexandria and Saqqara but also in Pergamon and Ephesus in Turkey.

Also of note for the Greek community is the 2,000-year presence of the Greek Orthodox church in Egypt. The Patriarchate of Alexandria, founded by Mark the Evangelist in 49 CE, was one of the five major episcopal sees of the Roman Empire and produced major thinkers of early Christianity. A schism within the church after the Council of Chalcedon in 451 resulted in the creation of the Coptic Orthodox Church. Today, Coptic Christians are the largest ethno-religious minority in Egypt, making up roughly 10 percent of the population.

The arrival of modern Greeks in Egypt began in the early 1800s, when its ruler Muhammad Ali invited Greek merchants to settle in the country and contribute to its economic modernization. One of them was Michael Tositsas, a successful businessman who became a personal adviser to Muhammad Ali and great benefactor of Alexandria’s Greek community. As the community’s first president, he chaired its inaugural meeting in 1843 to discuss the funding and organization of its fledgling school and hospital. Tositsas donated land for a third institution, the Cathedral of Evangelismos, and also financed the first community school, which now houses the Patriarchate.

Greeks and other non-Muslim minorities in Egypt enjoyed a wide degree of autonomy and privileges. The Capitulations, bilateral agreements between the Ottoman Empire and several Christian governments, exempted Greeks from local taxation and prosecution. The favorable economic climate and thriving community drew Greeks of all professions and social classes to Egypt, and they settled mainly in Alexandria and Cairo, but also in more rural areas along the Nile, where they worked as grocers, traders and money lenders. In the 1860s, Greek islanders from the Dodecanese came to work on the Suez Canal and settled in towns along the Canal Zone. Among these were the great grandparents of Dimitris Cavouras, who serves as deputy secretary on the board of the Greek Community of Alexandria and showed me around the city.

The American Civil War in the 1860s disrupted cotton exports from the South, creating high demand for Egyptian cotton in international markets. Many Greek merchants made their fortunes from the boom. Greek entrepreneurs also established a cigarette manufacturing industry in Egypt and engaged in food and beverage manufacturing, construction and textiles.

While touring Alexandria, I was surprised to find widespread references to Chiot mercantile families like the Zizinias, Salvagos, Rallis and Rodochanakis, whose summer estates I had visited last year in the Kampos neighborhood on the island of Chios. Those influential families who had offices in London and Marseilles and traded across the Mediterranean and Black Seas partook in Egypt’s flourishing cotton industry, and their wealth funded community institutions.

The Greek population continued to grow after Egypt fell under British rule in 1882 and reached its peak at about 100,000 to 150,000 people in the period between the two world wars. Many Egyptiótes remember that time nostalgically, and frequently described Alexandria to me as a cosmopolitan city home to Greeks, Jews, Italians, British and French. One recalled the “magnificent presentation of fruits and vegetables in the streets and sellers speaking a mix of Arabic, Greek and Italian.”

Most Greeks saw themselves not as conquerors like the British but workers making their daily wage alongside Egyptians, woven into the country’s social fabric. They ran restaurants, cinemas, hotels, night clubs, bakeries and barber shops and contributed to the city’s cultural and intellectual life.

The Alexandrian archaeologist Harry Tzalas complicates that picture. He told me the Greeks rarely ventured outside their quarter of the city and referred to common Egyptians as arapákia or arapádes, a pejorative term meaning “Arab or dark-skinned person.” Given the community’s size and diversity, there’s likely truth to both sides.

Britain’s occupation led to the growth of nationalist, anti-British sentiment and a series of demonstrations throughout the country that escalated into violence. When Britain ended its wartime protectorate of Egypt in 1922, the Egyptian government enacted legislation to end foreign privileges and increase Egyptians’ participation in the economy, especially in boardrooms and white-collar jobs.

Although alarmed by what those developments meant for their future in Egypt, the Greeks were unable to negotiate special treatment. When a nationalist military coup toppled King Farouk in 1952, they sided with the new government, and when Gamal Abdel Nasser, the new president of Egypt, nationalized the Suez Canal four years later, Greece supported the act. Although nearly all other foreign navigation pilots withdrew from the canal in an attempt to render it inoperable, Greek pilots remained at their posts.

However, Nasser’s nationalization measures made it increasingly difficult for Greeks to work in Egypt or obtain citizenship. In 1961, he reoriented the economy toward a socialist model, imposing state control over cotton production, banks, trade and manufacturing companies. As the government seized Greek firms and properties in the 1960s and a sense of instability grew, waves of Egyptiótes migrated to Greece, Australia, South Africa, Canada and Europe.

Today, about 3,500 Greeks live in Egypt, mostly in Cairo and Alexandria. Those who stayed were either determined to make the new Egypt their home or lacked prospects elsewhere. By and large, the Egyptiótes I spoke with insisted that they were not expelled from the country and that their exodus could not be compared with the forced migrations of Greeks from Istanbul. Cavouras described the mass departures as “collateral damage” as Egypt transitioned from colonialism to a fully independent, empowered nation state: Egypt for the Egyptians.

The Greek communities in Egypt today

These days, more Egyptiótes live in Cairo than in Alexandria. I found signs of their historical presence throughout the city, from the monumental Greek Campus building downtown, which housed the Achillopouleios school until it was sold to the American University of Cairo in 1964, to the Greek Center of Cairo, a former men’s club in the British style of the late 19th century that hosted kings, prime ministers and other prominent guests. I also enjoyed a sunset tea at the Greek Nautical Club, a blue and white houseboat on the banks of the Nile founded in 1930.

Past and present meet at the Greek Community of Cairo’s archive, where Haido Zotou and her team meticulously collect, clean, catalog and shelve thousands of books, ledgers, minutes, maps, architectural plans, photographs and artifacts from Cairo and 380 other dissolved Greek communities. I was impressed by both the scope and quality of the archive. Zotou hopes to expand the space and find collaborators to digitize the archive. “People then had another ethos, another character,” she said, showing me the calligraphic handwriting in an accounts ledger from 1907. “All this might have been lost if the community hadn’t invested in the archive.”

Christos Cavallis, an Egyptian Greek of Italian and Smyrniot descent who has served as president of the Cairo community for close to 22 years, met me at the downtown office to discuss the current state of affairs. Cavallis’s biggest accomplishment as president has been to create several revenue streams to ensure the community’s financial stability. He transformed the Greek hospital from a “black hole” into a profitable business, changed a statute for the retirement home so it could accept Egyptians as well as Greeks and created a translation department with the help of the Greek consulate to assist with visas and other paperwork. The three businesses support the community church, schools and cultural programs, employing a total of 400 people.

Cavallis arranged for me to visit the hospital and retirement home with assistant medical director Remon Niketaidis, an Egyptian-Greek intensive care doctor who has worked at the hospital for 17 years. It was established in 1912, and Niketaidis remembers visiting it as a child. He told me that over the past 10 years, the hospital facilities and level of care have increased significantly. Today it has 100 to 120 beds and a full range of specialties and subspecialties. As we toured different departments on the spacious 4,000-square-meter plot, he pointed out recent renovations, state-of-the-art General Electric imagining machines, a comfortable dialysis unit and a fully functional microbiology lab. I also met Ms. Cleopatra and Ms. Calliope, two of the retirement home’s Greek residents.

After successive waves of migration throughout the second half of the 20th century, Cavallis cited demographics as the main challenge the Greek community faces. “Our numbers are decreasing,” he said. “Young people are leaving, and the community is getting older.” Its composition is also changing. There are more mixed marriages by necessity, and since Greek is spoken only in school, the quality of language acquisition has decreased as well as children’s education as a whole because other subjects like mathematics and science are taught in Greek.

The small population also creates human resource issues. If the community can’t fill an open position for a psalmodist, journalist or teacher, for example, it has to bring one from Greece, and working permits are difficult to obtain. “Basically, we have to keep the few Greeks we have here, so they don’t leave,” Cavallis said.

Meanwhile, diplomatic relations between Greece and Egypt have been deepening since 2020, when the two countries signed a maritime delimitation agreement that overlaps areas claimed by a controversial 2019 Turkey-Libya agreement. According to Greece’s ambassador to Egypt Nikolaos Papageorgiou, the agreement with Egypt demonstrates how neighboring countries can cooperate in good faith with respect for international rights.

Greece and Egypt collaborate on natural gas exploration via the East Mediterranean Gas Forum, and during an August visit to Egypt, Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis and Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi also discussed the proposed Greece-Egypt or “GREGY” Interconnector that would link their countries’ grids, bringing renewable energy to Europe.

In addition, Mitsotakis affirmed Greece’s interest in Egyptian workers for the primary and construction sectors since Greece has a labor shortage while Egypt offers a large, young and relatively inexpensive workforce. Indeed, Dimitris Cavouras predicted a great labor movement from Egypt to Greece in the coming decades due to the countries’ physical and cultural proximity compared to labor from Pakistan and south Asia.

The countries agreed to convene a bilateral cooperation council involving several cabinet members in Athens early next year, signaling a commitment to further strengthen ties. As the Israel-Hamas war threatens stability and security in the eastern Mediterranean, Greece and Egypt both have a stake in ensuring a peaceful solution to the crisis.

Yet Greek community leaders have taken the political developments with a grain of salt. “It’s very positive on a psychological level,” Cavallis told me. “On a substantive level, no laws have changed for Egyptiótes since the 1950s.” When he met Mitsotakis in August, he proposed the reinstatement of the community schools’ “special condition” status within the Education Ministry to remove bureaucratic hurdles and facilitate fuller staffing.

He also requested that the government work with Cairo to grant Egyptian residence and work permits to second and third-generation Egyptiótes so they would not be forced to seek opportunities abroad. “I told the prime minister, ‘Many of my requests are copy-paste from my predecessors,’” Cavallis said. “‘I hope,’ I told him, ‘that it won’t be the same this time.’”

Dimitris Cavouras agreed. “International relations differ from personal relations,” he said. “What’s political is political. But now that the two countries are very close politically, we have the chance to do more to bring our peoples closer and closer. We feel that we are one with the Egyptian people. We are also Egyptian, we are not only Greeks.”

New partnerships and opportunities

The Greek quarter in the Chatby neighborhood of Alexandria is a complex of community-owned neoclassical buildings on a 52,800-square-meter plot near the modern Bibliotheca Alexandrina. It houses the community schools and offices, the Consulate General of Greece, a retirement home and the Athletic Union of the Greeks of Alexandria, a popular hangout for community members. In the elegant, high-ceilinged Hall of Great Benefactors where the board meets under the gaze of Michael Tositsas, George Averoff and other distinguished donors, Dimitris Cavouras told me, “Some people see us as just guardians with keys, but we have big plans.”

Indeed, a few days after I left Egypt, the community signed a memorandum of cooperation with the University of Patras to establish a branch of the university within the Greek quarter. The initiative, which takes place under the auspices of the president of the Greek parliament, was a milestone for the community, which has long sought synergies with academic institutions and foundations. “By partnering with the University of Patras to provide education to citizens of Alexandria, the community is fulfilling its mandate and acting as a bridge between Egypt and Greece,” Cavouras said.

The project is set to breathe new life into buildings of the Greek quarter that once accommodated thousands of students and that the community wants to renovate and maintain. Speaking to ERT News, community president Andreas Vafiadis promised, “any operation of a university branch will include the necessary protection and exploitation of Greek structures, buildings and monuments in the city, while manuscripts and archives that are in danger of being destroyed today will be preserved and digitized.”

The collaboration signals that the Greek community is continuing to adapt to new developments in Greece and Egypt while making the best use of its collective inheritance. As Yannis Melachrinoudis, the Cairo-born educational manager of the Greek Scouts Abroad told me, “The Greek community here will never be dissolved because it has a dynamism. Half of the buildings downtown were owned by Greeks, and when you say Younan (Arabic for ‘Greek’), Egyptians smile and say ‘friends, habibi.’ Our job is to teach young Greeks and Egyptians why that is.”

Wrapping up my ICWA fellowship at the end of September, I traveled through Greek Macedonia, home of Alexander the Great, and thought about how the legacy of Hellenism extends far beyond Greece’s current borders. The history of the Egyptiótes shows that Greece and the Greek people have much in common with the Egyptians and much to gain from embracing their historical role as a bridge between Europe and the Middle East. As conflict engulfs the eastern Mediterranean, strengthening ties between peoples in the region seems more important than ever.

Top photo: Students from the Greek schools in Cairo raise the Greek and Egyptian flags and sing the countries’ national anthems on the first day of the school year (Vassilis Poularikas)