ISTANBUL — It’s nearly impossible to walk down Istiklal Avenue without getting hungry. All along the bustling pedestrian street that runs from central Taksim Square through the multicultural district of Beyoğlu, shopkeepers tempt passing crowds from glass storefronts. Confectioners ladle thick honey onto pyramids of baklava. Street vendors in red vests knead globs of mastic ice cream with long sticks, holding out cones and then snatching them back to tease tourists. Doner kebab sellers shave juicy slices of lamb and chicken off vertical rotisseries.

Beyoğlu was historically a “Rum,” or Greek Orthodox, district called Pera, and one can still see traces of Greek names engraved on the neighborhood’s neoclassical buildings. One of the clearest connections between Greek and Turkish culture exists in the countries’ cuisines; the differences, although small, can be hotly contested. Greek baklava is generally more syrup-soaked and filled with walnuts, for example, whereas the Turkish variety is often lighter, crispier and filled with pistachios. Sometimes the only difference lies in a dish’s name: When ordering, I took care not to call a doner kebab a gyro or a Turkish coffee a Greek coffee.

Women in headscarves and facemasks strolled down Istiklal, admiring the many bold red Turkish flags hanging from windows or strung across the avenue. Couples stopped in the street to record videos or take selfies. I heard a woman chiding her children in Greek. Cognates leapt out from the Turkish conversations around me: the Turkish portakal and the Greek portokáli, meaning “orange”; kupa and koúpa, meaning “cup, mug”; köfte and keftés for “meatball.”

After a month living in the rural border prefecture of Evros, Greece, it was a bit of a shock to find myself in such a busy, cosmopolitan city. Even Ermou, the main shopping street in downtown Athens, seemed provincial in comparison.

Formerly known as Constantinople, Istanbul is the largest city in Turkey and its cultural, economic and historic center. The city was founded as the capital of the Byzantine Empire in 330 CE by Constantine the Great. As I discovered during my midnight bus ride across the Greek-Turkish border, my base in the city of Alexandroupoli lies midway between Thessaloniki and Istanbul. Alexandroupoli is the capital of the Evros prefecture, at the easternmost end of Greek Thrace. For more than a thousand years, the region’s proximity to Constantinople had huge ramifications for its development.

From a minor Roman province, Thrace became the center of the Byzantine Empire, enjoying the fruits of the capital’s cultural life and its constant attention. The region also served as Constantinople’s defensive shield. When Thrace fell to the Ottomans in 1371, Constantinople lost this vital bulwark, and the city was conquered less than a century later.

Fast forward to the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, which established the current border between Greece and Turkey. The new national borders separated Greek Thrace from Constantinople, which Angela Giannakidou, president of the Ethnological Museum of Thrace and my frequent companion to northern villages there, described as “severing a body from its head.”

Thrace’s separation from its historical capital and the frequent crises it has faced over the past century may help explain its underdevelopment. When Thrace joined the Greek state in 1920, its people, the majority of whom had roots in Turkey and Bulgaria, had to reorient themselves to a new “head” in Athens. They struggled to find a place in a Greek state that defined “Greekness” as one’s connection to ancient Athens and Sparta while overlooking the Byzantines.

The Treaty of Lausanne granted minority status to the Greek Orthodox community of Istanbul and the Muslims of Western Thrace, exempting both from a mandatory exchange of populations that displaced approximately 1.6 million people (1.2 million Greek Orthodox from Turkey and 400,000 Muslims from Greece). Although the Rum community was allowed to remain in Istanbul, decades of anti-minority policies including Varlik Vergisi—a discriminatory wealth tax enacted in 1942—the anti-Greek pogrom of September 1955 and forced deportations of 1964 have dramatically decreased their numbers.

For many Greeks, Istanbul is a city steeped in memory and longing. They still refer to Istanbul as Constantinople, or simply i Póli, “the City.” I visited Istanbul’s foggy shores to see what connections remain between the city and its historical periphery and what life is like for the Rum minority still living in Istanbul.

When I told friends in Evros that I was planning a trip to Istanbul, they repeatedly remarked how beautiful the city was and gave me suggestions about what to eat, chiefly Turkey’s famous flaky baklava. But most had not visited the city in years, citing tense relations caused by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Relations between Greece and Turkey have always been difficult, but two recent events convinced residents that the situation has escalated. In 2018, two young Greek soldiers were arrested by the Turkish authorities after crossing the Evros land border during a night patrol. The soldiers were detained for five-and-a-half months on suspicion of espionage.

Second, in February 2020, Erdogan pushed thousands of migrants toward Evros in an attempt to exert political pressure on the European Union. The tactic, which Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis called a “hybrid threat for Europe,” is being used again by Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko in retaliation for EU sanctions.

To be honest, I felt both excited and apprehensive visiting Turkey for the first time. In Greece, I generally feel confident traveling and conducting research because of my ability to speak the language, whereas in Turkey I had trouble retaining the most basic vocabulary, and few people I met spoke fluent English. I also knew that my connections with the United States and Greece would not necessarily help me in Turkey.

Just before my trip, Erdogan threatened to expel ten foreign ambassadors—including the US ambassador—over their support for a jailed activist. The LGBTQ+ community in Turkey has also faced widespread discrimination and harassment, so I felt the need to be extra-cautious when traveling with my partner Andreas. Amid Turkey’s democratic backsliding, a sense of instability prevailed. “Everyone’s just looking!” shopkeepers in the Grand Bazaar snapped. “What about just buying?” Over the past year, the Turkish lira had fallen from 14 percent to 10 percent of the dollar.

As I crossed the Kipoi Garden Bridge over the Evros River, the natural boundary between Greece and Turkey, I recalled black-and-white footage of forlorn Rum families walking across the same bridge during the forced migrations of 1964. That year, under the pretext of civil strife in Cyprus, Turkey deported some 13,000 Greek citizens from Istanbul within 18 months. Family members with Turkish citizenship had no choice but to leave as well. Their assets were seized, and they were forced to depart the country with only a 20-kilogram suitcase and the equivalent of $22 in their pockets. By the end of the 1960s, the Rum population in Istanbul had decreased from 90,000 to 18,000 largely due to those expulsions.

The last Greek newspaper in Turkey

On my first day in Istanbul, I met Minas Vasiliadis, editor of Apoyevmatini (“Afternoon” in Greek), Turkey’s only remaining Greek-language newspaper, at a cafe on Istiklal Avenue. With typical Greek hospitality, he took me to the terrace to show a panoramic view across the Golden Horn to the old city. I saw Topkapi Palace at the end of the peninsula and Hagia Sophia’s sunlit domes and minarets. Seagulls swooped in and out of view, and ferries crossed the Bosphorus, leaving white trails in their wake.

Turkish daily Cumhuriyet, Apoyevmatini is Turkey’s second-oldest newspaper. It has been published five days a week since 1925. The four-page paper covers politics in Greece and Turkey as well as graduation, marriage and obituary announcements from the Rum community. Hardcopies of the paper are delivered to the 600 Rum families remaining in Istanbul, and digital versions sent to some 2,000 subscribers around the world.

Minas was not much older than I, but he had a certain seriousness that seemed to correspond to Apoyevmatini’s status in the Rum community, as well as the personal responsibility he says he feels for keeping the paper afloat. He and his father Michalis are the paper’s sole employees. In 2014, they had to close their 90-year-old office on Istiklal, but they’ve continued to work on the paper from home. The newspaper’s financial struggles are emblematic of the demographic crisis faced by Istanbul’s shrinking Rum community.

“We are about 1,800 people, and we have all the problems of Turkish citizens plus our own problems as a minority,” Minas told me. “The average age of our community is 60 to 70. Who will have children? My father who’s 82 years old?” He laughed, a rare and surprising sound. “We are so few in relation to Istanbul’s population of 15 million that if the Ecumenical Patriarchate weren’t here, no one would be talking about the Greeks here.”

The Rum community’s soft power

Still, for a community of 2,000, the Rum in Istanbul exert an outsized cultural influence because of their long history in the city. The Orthodox Church has functioned continuously since the Byzantine Empire and through the five centuries of Ottoman Turkish rule that followed. As the capital of the former Byzantine Empire, Istanbul holds a special place of honor within Orthodoxy and serves as the seat for the Ecumenical Patriarch, the “first among equals,” who is regarded as the spiritual leader of Eastern Orthodox Christians. During my visit to Istanbul, the top news in Apoyevmatini was the Ecumenical Patriarch’s visit to the US and meeting with President Biden.

The famed Hagia Sophia, the largest Christian church of the Byzantine Empire and an icon of Eastern Orthodoxy, was built as the patriarchal cathedral in 537. After the fall of Constantinople, it was converted into a mosque by the Ottomans, and, under the direction of Turkey’s founding father Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, established as a museum in 1935. Last July, Erdogan controversially redesignated Hagia Sophia a mosque, which Christians in the city viewed as the conservative government’s latest nationalist move. When Andreas and I visited, Hagia Sophia still had the traffic of a major tourist site (“And now free admission,” friends quipped), but access to its upper galleries was restricted, and the cloth panels covering its exquisite mosaics seemed like a denial of the monument’s rich, multi-religious past.

“For years now, the religious have been talking about a ‘second conquest of Constantinople’ by Islam,” Alexandros Massavetas, author of Constantinople: The City of the Absent, wrote in a recent article in Kathimerini. “The authorities’ ‘weapons’ are the building of mosques and the attack on symbols of Western life.” He cited the president’s massive new mosque in Taksim Square, the first thing I saw when I arrived in Istanbul. The government’s goal, he wrote, is for the city’s central square to have an Islamic monument as its main landmark. “The mosque overshadows the Greek Orthodox Holy Trinity Church, visible from the square, while the Republic Monument, dedicated to secularist Atatürk, almost disappears.”

The Ecumenical Patriarchate faces ongoing pressures from Ankara. Turkish law requires that patriarchal candidates be Turkish citizens, an issue exacerbated by the declining Greek Orthodox population. The 50-year closure of the Theological School of Halki, the main institution training Orthodox clergy in Turkey, casts further doubt over the Patriarchate’s future.

The patriarchal church in Fener, home to the Patriarchate since 1600, is dedicated to St. George, the patron saint of Thrace. The saint’s iconography, riding atop a horse in the style of a Roman cavalryman while spearing a dragon, was adapted from the recurring motif of the Thracian Horseman, a great cult deity during the Hellenistic and Roman periods. Even today, Muslims in Evros continue to worship St. George on his feast day, April 23.

The influence of religion also extends to sports. In a side street off Istiklal, I found the wrought iron gate of the Beyoğlu Sports Club with its yellow-and-black logo, a color scheme taken from the Byzantine flag. The club’s roots date back to 1877, when the Rum community established clubs like Hermes in Pera for athletic competition. Founded in 1914, the Pera Sports Club changed its name to the Beyoğlu Sports Club after the establishment of the Turkish Republic in 1923.

Two famous Greek athletic clubs, AEK (Athletic Union of Constantinople) in Athens and PAOK (Athletic Club of Constantinople in Thessaloniki), trace their origins to the Pera Sports Club. They were established by refugees who came to Greece during the exchange of populations and wanted to carry the torch of the Constantinople club. Both organizations use the double-headed Byzantine eagle as their emblem and yellow and black as their colors.

In Alexandroupoli, a city built by Greek Orthodox refugees, there is strong support for clubs like AEK. “For us, sports clubs are like a family, a kind of legacy,” said Angelos Lolis, a longtime AEK fan who owns a restaurant named Achirónas. Angelos walked me to AEK’s “Original 21” supporters’ union just blocks from my apartment, opening my eyes to all the club-related graffiti I had passed every day. “All the Greek teams from Constantinople try to support the Pera Club,” he said. “We compete over who is the real refugee club.”

It’s no coincidence that a new AEK stadium being built in Nea Filadelfeia, an Athenian suburb settled by Greek refugees, was christened Hagia Sophia. The stadium has received the blessing and financial support of the Ecumenical Patriarch. I asked Angelos if he would visit the new stadium when it opened next year. “Of course,” he said. “It’s like Mecca.”

An impromptu graduation ceremony

I was surprised to find that I had already passed the Zografion Greek High School several times before I came for a visit. Indeed, the night Andreas arrived in Taksim, we ducked into a lokanta, a casual eatery with ready-made food, next door to the school to escape the rain. Located on a side street off Istiklal, the neoclassical building is flush with its neighbors and has a recessed portico decorated by four marble columns with two sphinxes in marble relief guarding the entrance.

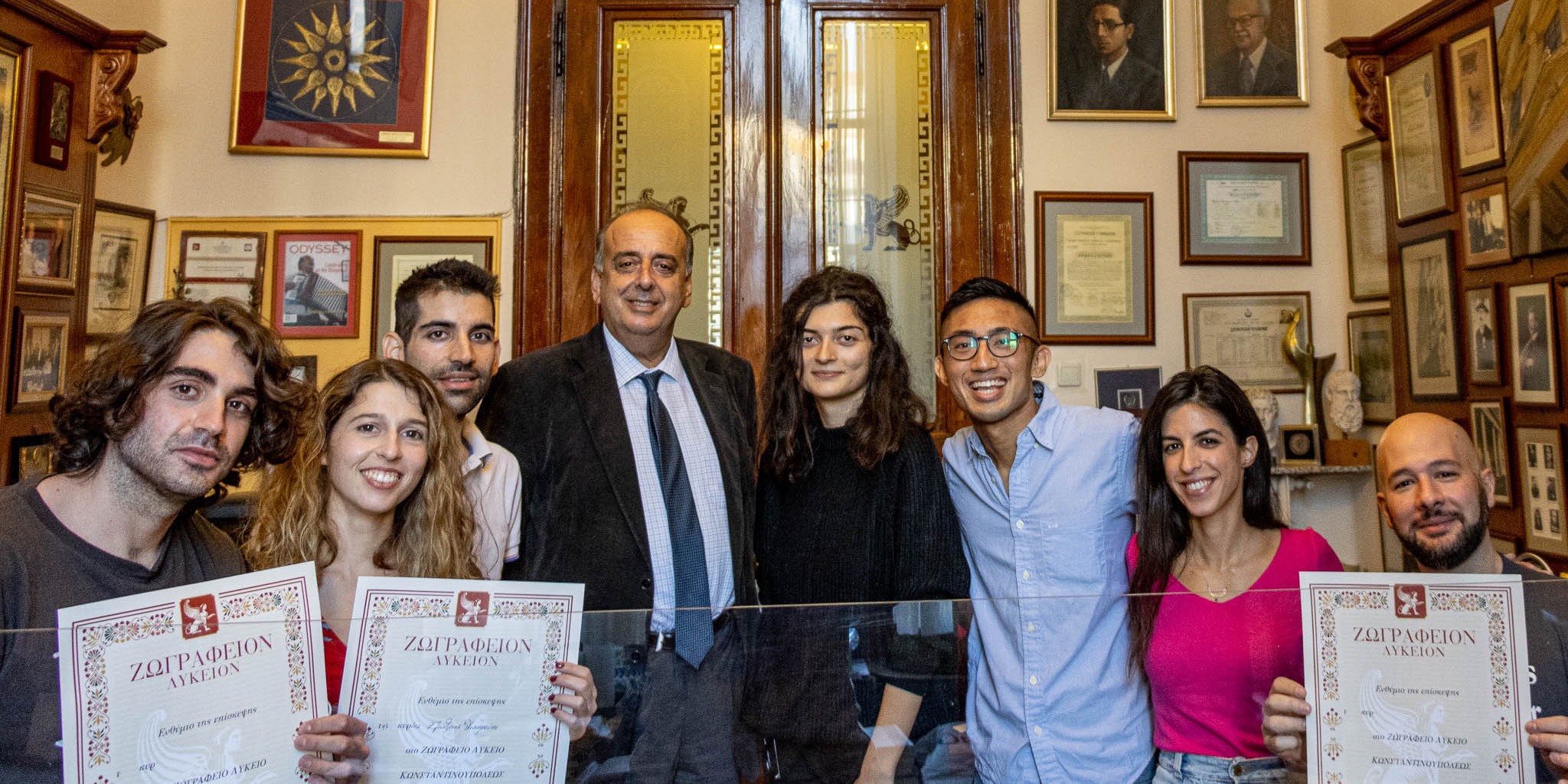

The afternoon I visited, Giannis Demirtzoglou, the school president, was meeting with a group of young Greeks, but he invited me to join them, offering me coffee and a seat in one of his plush leather couches. His office was well lived-in, filled with books, framed photographs, documents and paintings from the school’s 128-year history.

A tall and charismatic man who has held his office since December 1994, Demirtzoglou described how the declining Rum population affected enrollment at Zografion. In the 1959-1960 academic year, 644 students were enrolled; five years later, after the deportation of Greek citizens, there were 454 students. And after Turkey invaded Cyprus in 1974 and the military coup of 1980, enrollment dove to 152. Today, 47 students are enrolled at the school.

As we toured the building’s three floors, I peeked into beautiful, high-ceilinged classrooms with dark wooden desks and blue curtains and a bright art studio with watercolor paintings of the city’s mosques and minarets. Each classroom was kept in pristine condition, as if ready at any moment to welcome a new generation of students.

Demirtzoglou has spent his career serving the school and its students and helping to preserve the Rum community’s identity and traditions. Every Christmas, he puts on his accordion and takes the students caroling in Beyoğlu to help them connect with the community. He has also built Zografion’s reputation as a center for arts and culture by hosting over 550 concerts, symposia, trips and activities. He has brought internationally renowned Greek musicians like Dionysis Savvopoulos and George Dalaras to perform at the school, and he collaborates with the Mandoulidis Schools in Thessaloniki on an annual symposium on Greek language and literature attended by students from Greece, the US, UK, France, Egypt and Australia.

Over the past two decades, 94 percent of Zografion graduates gained entrance to institutions of higher education. The school is in talks with the Greek Education Ministry about recognizing Zografion’s diplomas so that its students can attend Greek universities. Demirtzoglou seemed optimistic: Last year, Education Minister Niki Kerameus visited Zografion and pledged her support.

Before we departed, there was one more order of business. The visiting Greeks and I signed the school’s guestbook, then Demirtzoglou called us up to his desk by name, rang a bell, shook our hands, and presented us each with an honorary graduation certificate. He gave us a school pin, a book about Zografion’s history and a coupon to the Koska baklava shop on Istiklal. “Zografion continues to be a meeting place for distinguished guests and friends from all around the world,” he said beaming.

I was struck by the warmth of our reception and Demirtzoglou’s skillful public diplomacy—creating a bond between us and the school, symbolically adding us to Zografion’s ranks with the impromptu ceremony. Then I remembered what Ms. Angela, the museum president in Evros, said while we were touring unused municipal buildings in the town of Didymoteicho: “The memory of a city lives on when its historical buildings are open and given new life. Culture isn’t just about the past. It isn’t a cemetery. Culture is life.”

For a community of 2,000 people, keeping important Rum institutions like the Ecumenical Patriarchate, Apoyevmatini, the Beyoğlu Sports Club and Zografion alive is itself a statement that despite all the hardships they’ve endured, the Greek Orthodox in Istanbul are still here, and the institutions they’ve built continue to have an impact beyond Turkey’s borders.

At the end of the week, I returned to Evros, the historical countryside of Constantinople, with as much baklava as I could carry. Since then, i Póli has stayed with me. I think about crossing the Galata Bridge at dusk as the evening call to prayer rang through the city. I think about the headscarved cashier at Koska who shyly told Andreas and me, “You two are very beautiful.” And I think about the 15 million people who call Istanbul home, living on an economic knife-edge.

As I write, the lira has fallen to 7.2 percent of the dollar, an all-time low. “Things in Turkey are not going well,” Minas told me. “It’s twice as difficult for the Greeks living here. That doesn’t mean we’ll give up and leave. We’ll stay here and do all that we can and wait for something to change. But in 2008, I had a lot more hope than I do now.”