NEW DELHI — In the early days of the lockdown, Geeta called a women’s helpline to file a police complaint against her husband. He had erupted in a violent rage after seeing her cats scratch their furniture, she said. But when a police officer came to their home to register an official complaint, he extended sympathy to her husband.

“I was told that good Indian women don’t complain and that this ghar ka mamla [domestic matter] should be resolved amicably by my husband,” Geeta said. (Her name has been changed to protect her privacy.) To her dismay, the officer also instructed the husband to “control” his wife.

A 35-year-old lawyer with a PhD in development economics, Geeta said she never imagined she would become a victim of domestic violence. “I come from a family of supportive and connected people,” she said. “Yet I was beaten and dragged across the floor.”

The incident has caused a complete breakdown in their marriage. She and her husband live in the same apartment with their six-year-old son, but now sleep in separate rooms to avoid each other. “I don’t have anywhere else to go because renting is impossible and so is [moving]” during the lockdown, she said.

Geeta is far from alone. The World Health Organization estimates that during emergencies and epidemics around the world, violence against one in three women becomes more deadly, leaving them especially vulnerable to conflict and displacement.

In India, where a third of women say they’ve suffered violence at the hands of their spouses, complaints to domestic violence helplines and aid organizations have spiked during the lockdown. Between March and May, these complaints were at a 10-year high. In a majority of cases, victims saw police assistance as one of their last options, reflecting a criminal justice system that favors the protection of marriage at the cost of women’s safety.

Escalating violence

Despite the enactment of some progressive measures after global outrage erupted over the infamous “Nirbhaya” Delhi gang rape in 2012—after which four men were executed for the sexual assault and murder of a 23-year-old student in a moving bus—physical and sexual violence remains deeply embedded in India’s patriarchal society. When respondents to a national survey in 2015-2016 were asked if beating or hitting wives is justified under seven different circumstances—including “refusal to cook food properly” and “disrespecting in-laws”—52 percent of women and 42 percent of men said they agreed.

The problem is exacerbated by women’s lack of access to the justice system, partly because of widespread illiteracy in addition to social subordination. Even the authorities acknowledge the problem: “The unfriendly process of law has kept most distressed women away from the law and courts,” a study funded by the Women and Child Development Ministry reads.

But the crisis has worsened under lockdown, with those in volatile domestic situations trapped with their abusers. Social isolation, increased financial stress and weak institutional support have helped boost the level of violence, according to the Mumbai-based Society for Nutrition, Education and Health Action (SNEHA).

In April and May, 1,428 women turned to the National Commission for Women, a government agency, with complaints of domestic violence—nearly double the number clocked between January and March.

In instances when women did not want to lodge formal complaints, many turned to aid organizations for informal support. SNEHA, which focuses on prevention through education and awareness in local communities, assisted an unprecedented number of women through counseling, according to the director, Nayreen Daruwalla. In May alone, the group’s counseling centers registered 343 cases, almost half the number recorded nationally by the government’s commission.

Experts believe the lockdown has affected both the frequency of assaults and level of violence.

In one recent example, a woman in Vadodara, a city in western India, called a toll-free help line administered by the state government: Her husband had assaulted her after repeatedly losing a board game, she said, delivering a beating that resulted in a spinal injury.

Urvashi Gandhi, an advocacy director at Breakthrough India—a community-based organization for women and girls—worries many victims risk death. “As a result, the whole domestic space has become extremely volatile, putting a lot of stress on the system,” she said.

Men who are usually out of the home for work are now forced to stay in. “They are frustrated and they want to exert their power in some way,” Gandhi said. “Even something as trivial as a wife buying some extra rations for the house is a trigger that can set them off.” Daruwalla said women previously had at least some time to recover from trauma when their partners were out of the home. “But now that whole coping mechanism has broken down.”

Family tradition

Domestic violence has long been considered a private matter under family law, not a public health concern. That makes addressing the problem especially difficult. Historically, the only legal recourse has been to seek divorce. But in a country with one of the world’s lowest divorce rates, the huge stigma attached to the dissolution of marriage—especially when children are involved—has discouraged women from pursuing it.

“Women will take every other option except reporting to secure the family’s safety,” Gandhi said.

Despite the recent rise in known cases, typically only one in ten victims of violence reported it to the police or a health care professional, a recent study found.

The accumulated evidence of casework by women’s groups over the past decades makes it clear domestic violence is “a problem without a name and without a law,” a report supported by the UN Trust Fund on Violence Against Women in India states.

If my boyfriend is kissing me in public, everyone will be alert. But if he is beating me in public, nobody will be.

The issue was finally addressed in the penal code only in 1984, when domestic strife and conflicts over dowries led to a higher rate of marital deaths, and cruelty by a husband or his family members became a criminal offense. However, even that development did little for women’s legal rights and protections, which remained further neglected until 2005, when the government enacted the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act.

Limits of the law

A civil remedy that does not determine criminal liability, the measure has nevertheless enabled women to seek relief through compensation, protection and the right to residence in the same household as their abusers. It also established protection officers (POs) in the police force who can record domestic incident reports, inform women of their rights under the law and facilitate access to support services.

But implementing the law remains challenging. “The police and courts often say to the women, ‘Why don’t you adjust for the sake of your family and children?’” said Shalu Nigam, an independent researcher who’s studied domestic violence.

She points to two Supreme Court rulings, in 2014 and 2017, as evidence of bias toward women who speak up. Where the act previously enabled the police to automatically arrest perpetrators on suspicion of having committed violence, both rulings order them not to because of the “misuse” of the law by “disgruntled women.”

Now, if a woman wants to file a complaint, the PO is required to investigate whether it’s justified. “The fallout is that cases are no longer easily registered,” Nigam said. “If I go to the police, the investigation officer has the liberty to make his or her own judgement.”

Tanvi Sharma, a lawyer from Volunteers Collective who has represented domestic violence victims, describes police intervention as “terrible.”

In one recent case, she said, a woman who worked as domestic help in Delhi filed a complaint against her husband on the insistence of her employer. But despite a provision enabling women to lodge complaints at any police station, she was told to go to the one near her own residence in a village miles away.

In another case described by SNEHA, the police were too “busy” to intervene when a 61-year-old woman in Mumbai faced violence from her mentally ill husband. In yet another, in which a man choked his wife with a pillow, the police actually called him rather than file a report—and “made them understand and stay together.”

Rural residents are especially at risk. “It takes a lot of effort for people to reach out to the police station because it’s such an alien place for anybody,” Sharma said. “If that’s the case in the big cities, what would happen to women in smaller states?”

Even if victims want to go to court, they require some legal assistance, she added. “Women in middle class families can reach out to lawyers,” Sharma said, “but those in the rural areas don’t even know anything about help lines or about these orders.”

Informal solutions to curbing violence against women have appeared with the invention of safety apps, rape whistles and hand gestures. In June, the National Commission for Women partnered with Twitter to launch a dedicated search prompt to update authoritative sources on domestic violence issues. “With social distancing norms in place, some women are unable to contact their regular support systems,” the Commission’s chair Rekha Sharma said. “This initiative by Twitter will provide big support.”

But the reach of such initiatives is limited by a lack of internet access to only a third of India’s 1.4 billion people, of which only 30 percent are women.

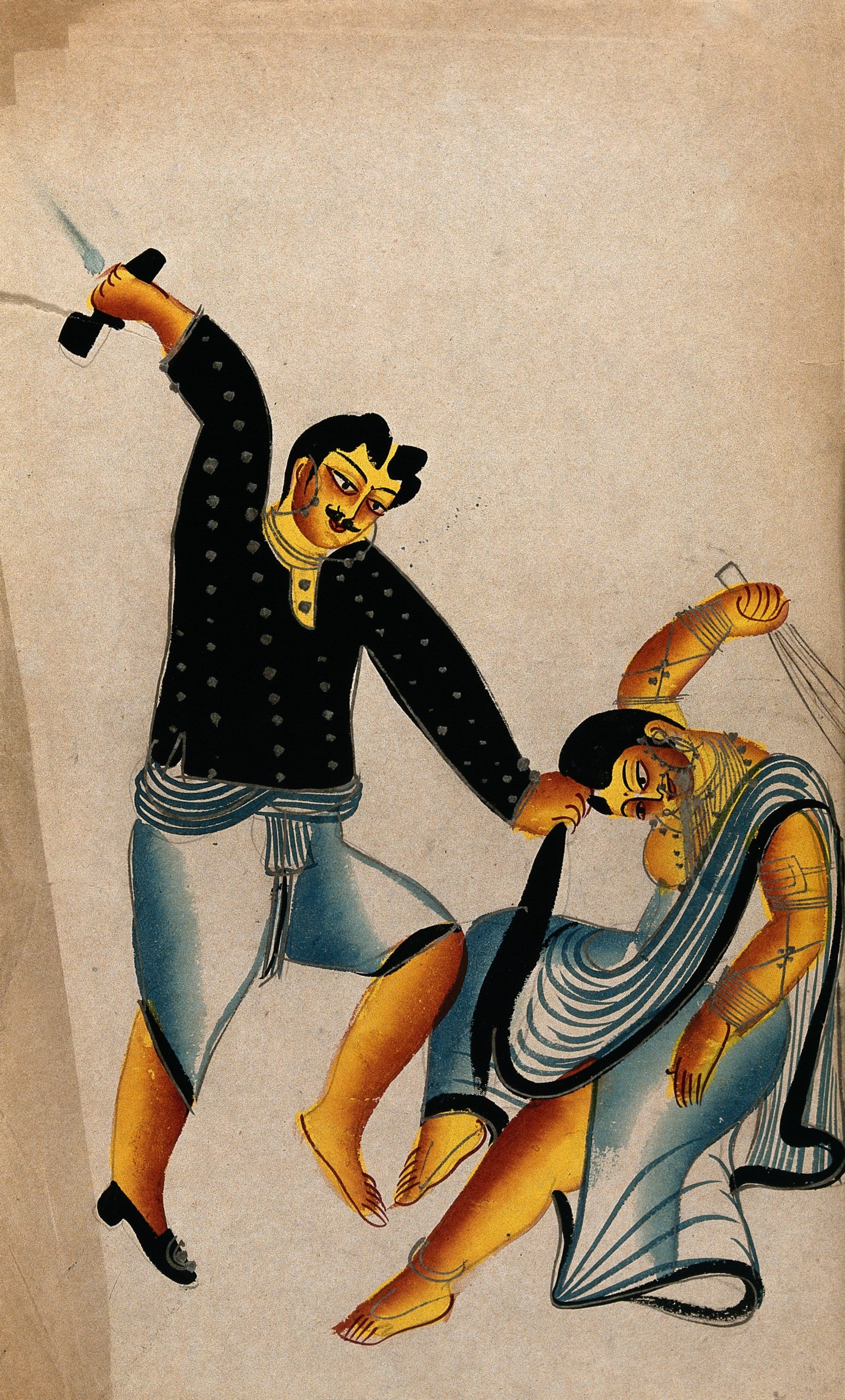

In a watercolor, a husband about to strike his wife with a shoe as she tries to defend herself with a broom (Wellcome Library)

Looking ahead

Hoping to reinstate normality and restore the economy, several cities across the country have been loosening lockdown restrictions since late May despite a new spike in Covid-19 cases. Notably, liquor stores were among the first businesses to reopen in the capital.

“As liquor consumption increases, so does violence against women,” Nigam said. “And yet we have done nothing to ensure women’s safety.”

Advocates suggest a number of ways to assist domestic violence victims during the pandemic.

When informal help lines began appearing online in April, Volunteers Collective wrote a letter to the Women and Child Development Ministry to suggest establishing only one universal help line for victims in every state. The group also recommended more shelters, on-call counseling services and creating “a seamless flow” of information between local police officials and protection officers.

In Geeta’s case, relief eventually came toward the end of May, when Delhi’s district courts finally reopened online hearings. She was able to file a domestic incident report and seek an interim protective order against her husband to secure the right to safe residence.

In the absence of any formal assistance during the first two months of the lockdown, her support systems had been informal—a “sisterhood group” of friends on WhatsApp, along with her family. “I was helped by so many lawyer friends and my sister, a specialist social worker,” she said. “It would be torture for anyone less connected.”

Experts agree that although better implementation of the laws is necessary, society first needs to ditch its patriarchal mindset. “If my boyfriend is kissing me in public, everyone will be alert,” Nigam said. “But if my boyfriend is beating me in public, nobody will be alert.”

One way to do that, she added, is to make families function more democratically and ensure the burden of caring for the home doesn’t fall squarely on women. “Everyone should play an equal role.”

Still, she said, such changes would be possible only if the courts, police and, at the very least, family members start listening to women first.

Top photo: A bride arrives at her new home (Wikimedia Commons)