Note: This is the second of two dispatches examining women’s employment in India.

NEW DELHI — Last September, Radhika Mathur decided to pursue her lifelong dream of starting a fashion label. Now in her early 30s, the graduate of New York’s Parsons School of Design had lived in Britain as a child and worked for brands in New York and Dubai. Moving to India presented an opportunity like nowhere else: It is home to a large textile industry, with lax regulations that are conducive to entrepreneurship.

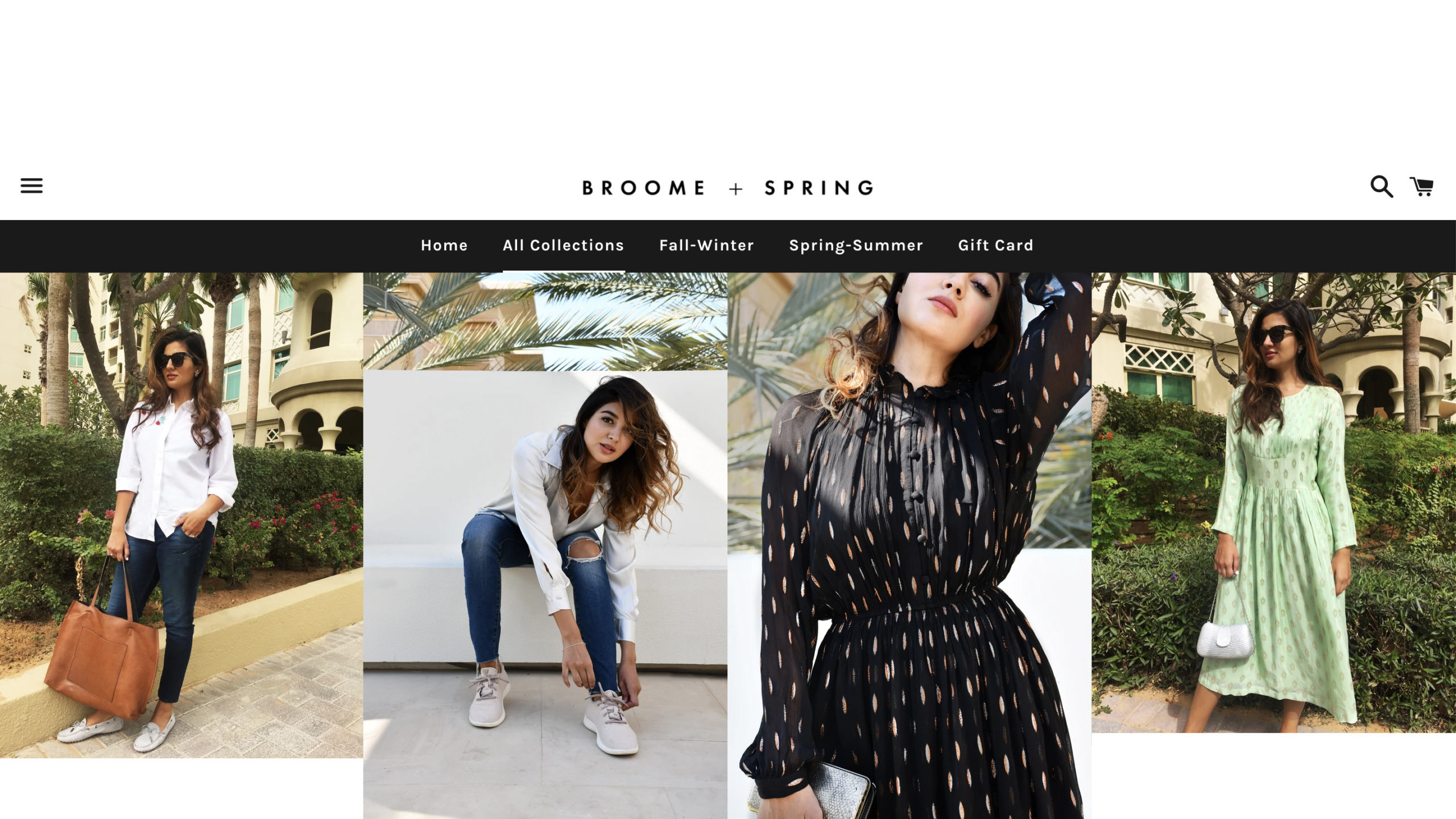

Spotting a gap in the market for contemporary wear, she launched her first collection, called Broome + Spring, with financial help from her father. An ensemble of chic designs inspired by New York with colorful prints to pay homage to India’s rich textiles, Mathur hoped to cater to women like herself: young professionals who enjoy luxury in India’s urban centers.

But six months later, bundles of unsold stock were gathering dust in her home studio, a small room in her family home in the district of South Delhi, which had been converted for designing, displaying and selling her designs. The Covid-19 outbreak and subsequent lockdown had brought her business to a screeching halt. The season for her collection was also over—on top of her cash supply. “I sat there wondering, ‘Who did I produce all this for?’” Mathur said, impatiently brushing back her long black hair. The collection reflects her refined, upscale taste.

Women like her, who are managers or entrepreneurs, are few and far between in India. Only 27 percent of employed women work in the formal employment sector, holding jobs with contracts and salaries. And as the country’s economy suffers the fallout from the pandemic, many also face major setbacks: mounting job losses, increased financial pressures and a widening gender gap in the workforce.

There’s another struggle: Mathur believes Indian women who want to run their own businesses need to fight the perception they’re simply pursuing a hobby. “I had to prove myself to everyone, including my own tailor,” she said of her experience starting out. “There were lots of times the respect just wasn’t there. It’s a battle that I think you fight a lot.”

An uneven playing field

Between April and August, 21 million salaried workers in India lost their jobs, according to a survey by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy. Those with professional qualifications, such as engineers, teachers and accountants, were hit particularly hard.

But for women business owners, who already face inequity due to low investment, the impact was disproportionate in other ways: Without immediate financial relief, one in three female-owned businesses shut down or were temporarily closed, with the owners now returning to the domestic sphere—where they already spend 577 percent more time doing unpaid work compared to men, according to a study by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Indian women have long faced an uneven playing field. They are still subject to old laws governing which industries they can work in and when. In the 1990s, female participation in export and manufacturing jobs fell, despite increased trade, because of factory laws constraining women’s working hours. Even when laws change, employers are more likely to hire qualified men because of existing norms around women’s work, according to a study by Harvard University.

The caste and class system have also regulated labor markets and traditional occupations: Women belonging to the wealthier Baniya caste tend to own shops and small businesses, for example, while poorer ones serve as vendors or peddlers. But the notion that a woman’s responsibility lies in the domestic sphere is even stronger among upper-caste households, meaning economic growth alone may not boost wealthier women’s ability to work.

The pandemic’s economic impact on the meager 20 percent of women-led businesses has also been far-reaching in other ways: These ventures provided jobs to some 22 to 27 million people, who are also facing losses as a result.

Fighting to the top…

An award-winning architect who had worked on projects in 13 countries, Priyamwada Singh moved back to India 10 years ago to start her own architecture firm. She had taught in architecture schools and held prestigious fellowships in the United States, but despite her deep experience, clients in India repeatedly expressed disbelief that she was in charge. “They’d always allude to me as ‘the artist’ and ask if there was a man handling the technical side of the project,” she said.

Indian women are still subject to old laws governing which industries they can work in and when.

But Singh, now in her early 40s, grew up in a family where patriarchal norms often took a back seat. Her father and brother encouraged her to start her own firm, and she quickly became one of only a few female leaders in India’s exclusive luxury housing market.

But during the lockdown, she experienced the unique difficulties of remotely managing a team as a female boss. There were pay cuts across the board, one employee was laid off and eventually, Singh decided not to take a salary—the result of the pandemic-induced economic turmoil that has hit women harder than men. It was a “double-edged sword,” Singh said: “You’re expected to be understanding, and as a result, you sometimes have to be more aggressive to get things done.”

Fortunately, there were some upsides. Being single allowed her to spend more time looking after the business, which was able to survive the lockdown because more people undertook home improvements while shuttered inside. But cultural expectations still loom over her achievements. One sentiment she’s picked up from others—whether explicit or implicit—is Ghar to ladki ko hi sambhalna hai (“The woman must manage the household”).

For her part, Mathur, the designer, lost thousands of dollars in production and sales, and was forced to call her suppliers to cancel production on a seasonal collection she’d just spent months designing. But she was also lucky, since her father advised her on her business. Having her parents’ support made the decision to continue with the label easier, she said.

… and fighting for a brighter future

Still, Mathur argues, support for women starting their own businesses remains superficial in India. “There’s a lot of change that needs to happen,” she said.

One option is to increase the government’s contribution to the Employees’ Provident Fund specifically for women, writes Prajakta Kuwalekar, co-founder of Engendered, a start-up focused on gender equity in the workplace. Stimulus packages and similar schemes can help achieve greater socioeconomic equality, although the chances of passing them remain low because gender equality just isn’t a factor when lawmakers consider new legislation.

Ultimately, domestic pressure often has the biggest impact on a woman’s decision to enter the workforce: “Continuing to work is a daily choice—which is rarely made by women alone,” economist Mitali Nikore writes.

With women already making strategic decisions regarding family life at home, enabling more of them to enter and lead the formal workforce would require more support from family members, Mathur says: “We need to recognize how much women are capable of doing.”

Top photo credit: Common Ground Practice LLP