NEW DELHI — The third time the Patiala House District Court denied Safoora Zargar bail in early June, Judge Dharmender Rana rejected her plea with a terse metaphor: “When you choose to play with embers, you cannot blame the wind to have carried the spark a bit too far and spread the fire.”

The “fire” that Zargar—who was arrested for sedition two months earlier—is suspected of stoking was the riots that erupted in North East Delhi in late February. The police accused her under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) of inciting violence by making inflammatory speeches.

She’d first appeared on the authorities’ radar last December, when she began participating in student protests at the predominantly Muslim Jamia Milia University in Southeast Delhi. Zargar was a media coordinator for the Jamia Coordination Committee (JCC), a student group organizing protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), which fast-tracks citizenship for all non-Muslim immigrants, and the establishment of a National Registry of Citizens (NRC) in the state of Assam, which has stripped nearly two million Muslim residents of their citizenship.

From mid-December into the new year, momentum began building across the country as thousands of students spilled onto the streets. Reports of police charging at protesters with batons and firing tear gas only fueled popular anger.

Most demonstrators were forced to retreat indoors by March as a strict nationwide lockdown took effect to stem the spread of the coronavirus. But that didn’t stop police from rounding up government critics—including nearly a dozen student activists like Zargar, along with an unknown number of protesters—to charge under UAPA, which human rights activists claim the government has used to quell peaceful protests.

When officers came knocking on Zargar’s door on a Friday afternoon while she was napping, the 27-year-old sociology student from Kashmir had learned she was pregnant only weeks earlier.

Today, even as the Covid-19 pandemic continues raging, more than a dozen sit behind bars waiting to be acquitted, or at the very least, released on bail. Zargar’s story has come to exemplify their increasingly bitter struggle against a Hindu nationalist government working to suppress political dissent.

* * *

Zargar’s student group JCC traces its roots to December 15, when police and paramilitary forces broke up a peaceful march. Dressed in riot gear and civilian clothes, up to 2,000 uniformed men stormed on campus—breaking the locks on gates and windows along the way—and charged at students. At one point, the police beat around 20 people they lined up in front of the library, according to a report by the independent People’s Union for Democratic Rights. Others studying for exams inside the library were interrupted by the sound of explosions as officers firing teargas chased frantic students inside. Many captured the chaos on video. Some reports said police also fired at least three bullets at students.

Following that incident, a 19-year-old sociology student from eastern Jharkhand state named Akhtarista Ansari joined the JCC alongside Zargar. She and several other women at the university had already organized a series of marches. Ansari told me she felt it was her moral duty to “fight for our dignity, equality and liberty.” As a Muslim woman, she had experienced increasing Islamophobia after criticizing the government on social media. “The moment I post anything, [Hindu nationalists] start calling me ‘jihadi’ or ‘Pakistani’ and threaten to rape me,” she said.

After the police began cracking down on activists, she and many other students left their campus housing to go into hiding with friends or relatives to avoid police interrogations. A graduate student named Satya Prakash said that even in late June, students were receiving notices and phone calls from the Delhi Police Crime Branch summoning them to the station for questioning.

UAPA, the country’s primary counterterrorism legislation, has made all that possible. Denounced as draconian by experts as well as activists, the law lends itself to broad application thanks to its ambiguous definition of what constitutes terrorism: any act “likely to threaten” or “likely to strike terror in people.” The measure has given the government unbridled power to designate people as terrorists even if they haven’t actually committed any such act, according to Mrinal Sharma, a policy adviser at Amnesty International. It also dramatically restricts the rights of those accused, particularly by denying them the possibility of bail.

But it is not a new innovation. First passed in 1967 in response to India’s wars with China and Pakistan, the original UAPA enabled the government to declare any organization “unlawful.” More recently, the law replaced its subsequent (and now repealed) predecessors, the Prevention of Terrorism Act and Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act after terrorist attacks in Mumbai in 2008. In 2019, the act was further amended to enable the government to designate anyone a terrorist with no trial—which directly violates the UN’s International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Even more troubling for activists, UAPA reverses the burden of proof in certain instances, allowing the police to conduct searches, seizures and arrests at their discretion, depriving the accused the opportunity to challenge their arrests. The police are given nearly six months to investigate a case and detain someone without evidence. In the United States, by contrast, a suspect can be held for up to 14 days while Britain allows detentions of up to 28 days. “The purpose of UAPA is not to convict, but to put everybody behind [bars],” said Mihir Desai, a lawyer for activists.

Since its most recent amendment, UAPA has become a handy tool for quashing protests and persecuting protesters pushing for Muslim rights. When the citizenship act was first enacted, several leaders from Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party began raising Hindu-Muslim relations as a central polling issue across the country. During the Delhi Legislative Assembly elections in February, Home Minister Amit Shah told his constituents (including Muslims) that fears over the CAA were overblown as propaganda against his party, and at a virtual rally in the state of Bihar in June, he targeted protestors by praising the act.

The authorities used UAPA not only to arrest or detain over 3,400 people in connection with the Northeast Delhi riots but also target several journalists reporting on unrest in the territories of Jammu and Kashmir. Most recently, Judge Rana, who had earlier rejected Zargar’s plea, also granted the Delhi police an extension of an investigation of Shifa-Ur-Rehman, the alumni president of JCC.

As a result, boilerplate phrases like “terrorism,” “anti-national” and “conspiracy against India” have become linked with Muslim activists in public discourse. That dismays Zargar’s lawyer Nitya Ramakrishnan. “What a government considers a threat depends on the ideology of the moment,” she said. Guneet Kaur and Aiman Khan, of the Detention Solidarity Network, agree. The authorities have “used the investigation [into the riots] to construct a bizarre spiel that is aimed to falsely link human rights activists, Muslims and students who were active in Anti-CAA protests to the violence,” they tweeted.

Their treatment has differed from that of Hindu nationalist gunmen who were also arrested, for attacking protesters, outside the university in February: They were later granted bail. Meanwhile, the bail pleas of all activists in 2019 were rejected several times, including by the Supreme Court.

* * *

Ansari, the university student, said she was shocked to learn about Zargar’s arrest. “This would not have been possible before, as we would have protested on the streets,” she said. “But right now, the government is using the lockdown as an opportunity to suppress dissent.”

The Delhi police, however, say the case against Zargar has been “clear and cogent.” Witnesses and fellow suspects implicated her in causing “large-scale disruption and riots” across the capital and other parts of the country after a speech she allegedly gave in Delhi’s Chand Bagh Muslim quarter in February. She was ready to go to any extent possible, from a “small scuffle” with the police to advocating and executing a secessionist movement by “propagating an armed rebellion,” the police charge sheet stated.

Although the pressure on activists is daunting, student protesters say they’ve never felt more emboldened to speak out.

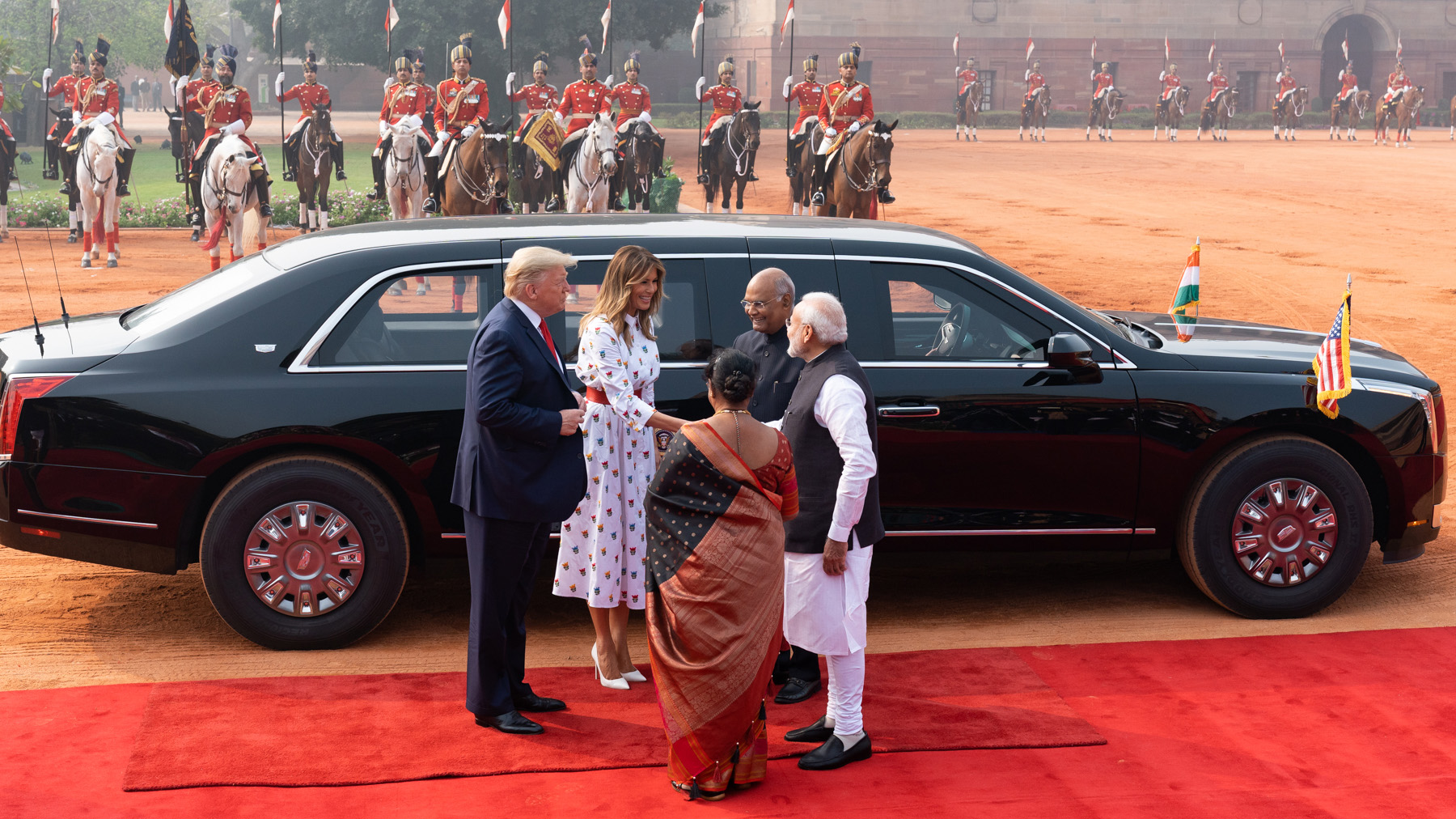

The riots erupted during President Donald Trump’s visit to India, which the police claimed was deliberately timed to “attract international media attention to propagate a narrative that the government of the day was anti-Muslim.”

Zargar’s lawyers argue the authorities are falsely connecting students to the unrest. She couldn’t have delivered an inflammatory speech on the day the police allege because she wasn’t even in the area, as her phone records show, they said filing her bail application a third time. After exhausting all possible legal arguments, they asked for bail on humanitarian grounds. More than five months pregnant by then, Zargar was also suffering from pre-existing health conditions including polycystic ovarian disorder, making her even more vulnerable during the pandemic. Judge Rana responded by ordering only that she be provided with “adequate medical aid and assistance.”

Nevertheless, the Delhi High Court finally granted Zargar bail on humanitarian grounds two weeks later on terms that prohibit her from engaging in any activity that could “influence” the ongoing investigation against her. The prosecution had argued her pregnancy did not warrant bail and that rearing a child should have served as “a check” on her activities, saying over three dozen births had successfully taken place in Delhi prisons over the last 10 years. Upon her client’s release, Ramakrishnan told a local online outlet called The Wire that “equating dissent with criminality is as pernicious as it is dangerous and a trend that must be most strongly opposed.”

But Zargar’s bail has no bearing on the cases of other women still detained. They include Natasha Narwal and Devangana Kalita, graduate students and co-founders of Pinjra Tod (“Break the Cage”), a women’s collective heavily involved in the protests. Both were granted bail after their arrests until the police immediately arrested them on other charges under UAPA. Gulfisha Fatima, an MBA graduate arrested on the same grounds as Zargar, had her petition for habeas corpus rejected the same week Zargar was finally granted bail.

The United Nations, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have all condemned the charges against them and others, demanding their immediate release. In July, the Delhi Minorities Commission, a government body, also released a fact-finding report on the February violence in the North East Delhi district, heavily contradicting the official accounts and chiding Delhi police and BJP leaders for their complicity.

But although the pressure on activists is daunting, JCC members said they’ve never felt more emboldened to speak out. Their sense of purpose appears to be felt particularly acutely among women, who Ansari and others say have driven the movement. “It was the first time we saw a lot of Muslim women wearing burkha or hijab out on the streets, carrying their identity,” she said.

“Many people are used to the idea of Muslim women being confined to four walls,” a second-year international relations student named Saud Ahmed said. But “those women were out on the streets, fighting for their identity.” The women had crucial roles in the decision-making process and on every other level, he said: “The success of this movement can singularly be attributed to women.”

Muslim women say they have felt increasingly compelled to speak up because the CAA and NRC actively disenfranchise women more than men. In Assam, for example, women are finding the burden of proving their citizenship by producing legal documents more difficult than men because patriarchal norms have often deprived them of land or property ownership.

Ahmed believes the government’s arrests of female activists like Zargar were meant to send a “direct message” to instill fear. “If they can arrest even a pregnant woman and deny her bail, then slander her reputation for being pregnant, they will not spare anyone regardless of gender or personal circumstances,” he said.

A non-observant Muslim, Ahmed has increasingly felt communal hatred directed at him, including inside his closest circles. Friendships of over 15 years have ended, he said, because he “realized there was no purpose in serving those friendships.”

In early June, Delhi witnessed the first scenes of public protests since the national lockdown when a few students—wearing masks and maintaining social distance—stood outside the campuses of Jamia Milia University and Jawaharlal Nehru University hoisting signs demanding the release of detained students. The protest was also carried out online under the same name, “Sab Yaad Rakha Jaayega” (“Everything Will Be Remembered”), a nod to a poem by the Indian activist and poet Aamir Aziz.

Around ten students were detained and later released. More recently, Pinjra Tod and other student activist groups here and abroad have continued posting on social media using the hashtag #SabYaadRakhaJaayega.

For now, the government remains distracted by its attempts to get the pandemic under control. Meanwhile, Muslim student activists say they won’t let their cause be forgotten. “This protest never ended,” Ansari said. “We will come back to the streets and fight for our comrades who are in jail.”

Top photo: Jamia Millia Islamia students protesting, December 2019 (DiplomatTesterMan, Wikimedia Commons)