DADIA, Greece — I met Angeliki Demiri on the morning of Epiphany after she caught me in a moment of indiscretion in the village church of Agios Nikolaos. Also known as the Theofánia, literally the “vision of God,” or H Yiortí ton Fóton, The Festival of Lights, this celebration is held each year on January 6 to honor the baptism of Jesus Christ and the revelation of him as the Messiah and second figure of the Holy Trinity. Considered one of the biggest feast days on the Greek Orthodox calendar, it also marks the end of the holiday season.

In the northeastern city of Alexandroupoli and other towns near rivers, lakes or the sea, Epiphany celebrations include the blessing of the waters, when a priest throws the holy cross into the water amid the singing of chants and honking of boats. Then the faithful—often a group of energetic young men—dive in, braving the chill to retrieve it. The one who returns the cross is said to be blessed for the year ahead.

I had planned to attend the festivities at the port of Alexandroupoli, but on the eve of Epiphany, Angela Giannakidou, president of the Ethnological Museum of Thrace, called to tell me about a unique ritual performed in the village of Dadia with ties to practices of ancient magic. The custom had been canceled last year due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but she’d gotten word that it would be happening this year, and she thought I’d be interested in seeing it. So, the next morning, instead of scouting out a prime location at the port, I found myself driving away from the sea to the north.

The village of Dadia sits at the foot of the Rhodope Mountains, next to the Dadia-Lefkimi-Soufli Forest National Park, which covers 428 square kilometers and is home to some of Europe’s rarest birds of prey, including three of four species of European vulture, the white-tailed eagle and the imperial eagle. Centuries of low-intensity land use has created clearings, pastures and fields within the pine and oak forests that are ideal habitats for those endangered birds. WWF Greece has a presence in Dadia, running educational programs, securing food for the vultures and helping with the management of the park.

Inhabited since the Byzantine era, Dadia was known as Cam-i Kebir, “the village of the big pine tree,” under the Ottoman Empire. Many of the village’s inhabitants originally came from northwestern Greece’s Epirus region, which observes similar customs. According to local lore, however, Dadia was founded by lumberjacks escaping from a plague. It grew with the arrival of refugees from Bulgaria and Turkey. The village’s present name comes from the resinous pinewood kindling used to start fires.

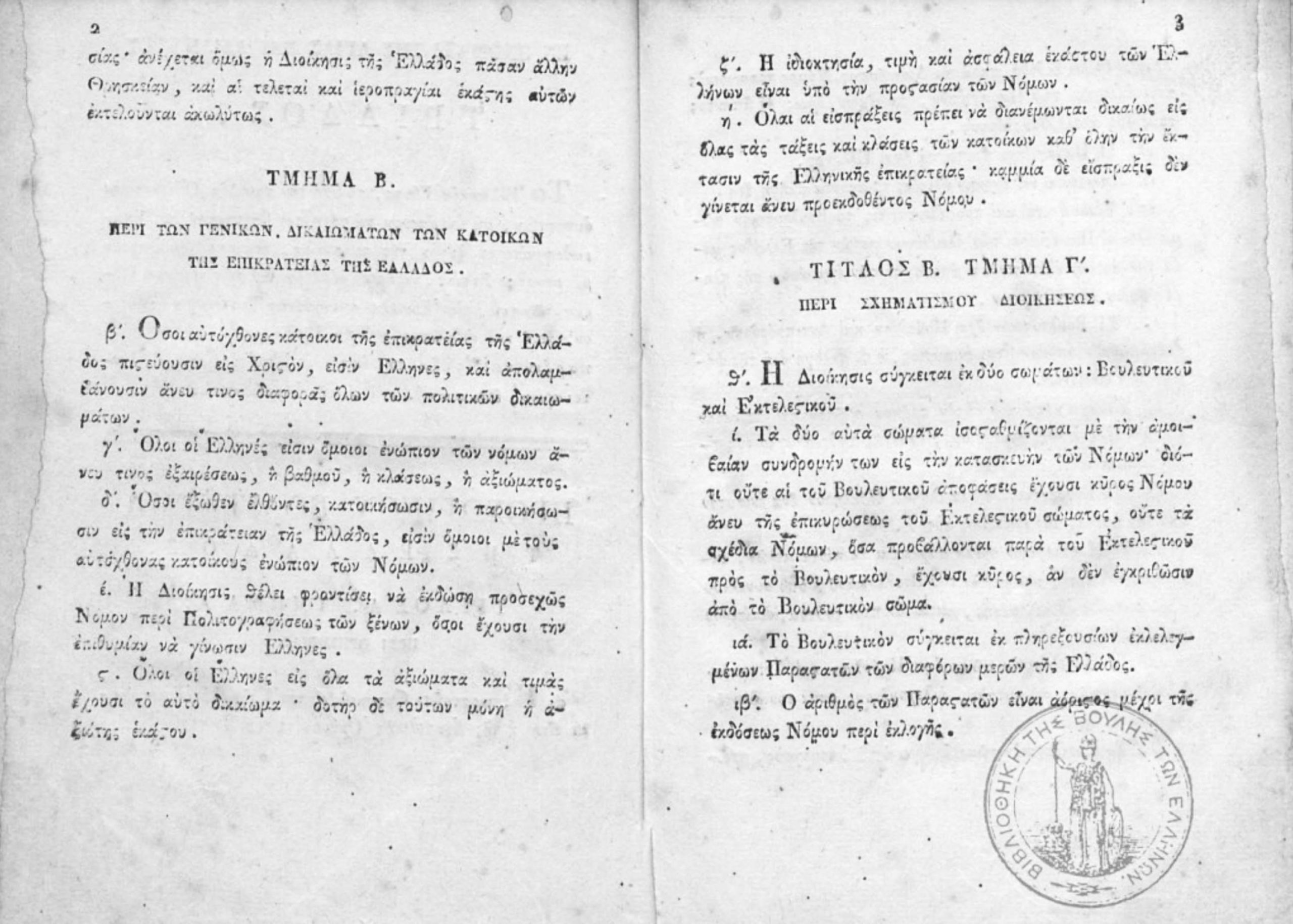

Dadia’s central church of Agios Nikolaos, built in 1840 and expanded in the late 1960s to accommodate a growing population, now seems large for its parish of 360 inhabitants. Dominating the main square, its red dome and bell towers can be seen from every point in the village. When I pulled up to the building, the bells were ringing and a group of masked and jacketed congregants huddled outside. I found a spot just inside the entryway to the nave to observe the proceedings within.

At the front of the church, surrounded by a group of young men, four suited officials carried a framed and garlanded icon of the Panagia, the Virgin Mary and child, which they’d brought down on foot from the Monastery of Dadia, three kilometers away, the afternoon before. The icon was recovered in 1941 from the rubble of the old, bombed monastery after the Virgin Mary appeared to a local woman in a dream, according to Giorgos Catsadorakis’s recent book about the forest of Dadia.

Páter Ioakim, the village priest, announced over the loudspeaker that this year, due to COVID-19, the church would be holding a reduced version of the annual custom. “You see that the virus circulates among us,” he said. He urged the villagers to observe the government’s measures and not take any photos or videos. “Don’t upload anything,” he said.

Leaning against one of the large double doors, I weighed my options, wanting to both respect the priest’s request but also document the day’s events. I watched a young man in front of me raise his phone to snap a photo. A few pews ahead of him, a middle-aged woman did the same. So, I took my chances, clicking two pictures of the Panagia flanked by solemn men when the priest turned his back. Worse comes to worst, I figured the laws of Greek hospitality would protect me.

For a minute or two, nothing happened. Then I heard a female voice behind me politely but persistently trying to get my attention. I turned to face a woman who motioned to my phone, telling me in Greek that photographs were forbidden. “Svíste ta,” she kept saying. She wanted me to show her that I had deleted the photos.

That’s when an outgoing young woman with a pink scrunchie and leopard-print face mask intervened. Angeliki had been standing next to me in the entryway and she told the woman, who happened to be her aunt, that others were snapping pictures as well. She was a nurse from Dadia who had spent four years in Germany before returning home. Now she worked at a health center in the nearby town of Soufli.

She offered to go up to the gynaikonίtis, the second-floor gallery reserved for women, to take photos to replace the ones her aunt had asked me to delete. A self-proclaimed choriátissa or village girl with a loud, infectious laugh, she invited me for coffee and later brought me home to try her mother’s cheese pie and a traditional dish called bámbo, minced meat wrapped in pork intestines and served in broth with lemon and black pepper.

Village life sometimes feels like living under a microscope, your every action watched and discussed. Angeliki later told me that after everyone had seen us walking “hand-in-hand” during Epiphany, they’d badgered her with questions. How did you meet? Did you know him before? Even the priest asked her if we were dating, rubbing his index fingers together in the Greek gesture for intimacy.

With Angeliki as my guide, I spent three days in Dadia learning about the customs that regulate village social life. While I expected Orthodoxy to play an outsized role in local affairs, I was also impressed that this millennia-old institution, which had absorbed pagan rituals and helped to catalyze the 1821 Greek Revolution, continues to adapt to the challenges of the ongoing pandemic.

* * *

At the end of the service, after Páter Ioakim blessed the water in the baptismal font and sprinkled us all with holy water, the men who had been standing at the front of the church exited in a procession carrying a wooden cross and nine icons of various sizes. There was the shaggy, winged figure of Agios Ioannis Prodromos, or Saint John the Baptist, carrying his own severed head. Then came the graying Agios Nikolaos, with Christ and the Virgin Mary floating on clouds over his shoulders.

Among these icons, too, were Profitis Ilias, the Prophet Elijah, and Agios Athanasios, gathered from smaller churches and chapels the day before and kept overnight in Agios Nikolaos with the Panagia. In his excellent book on the folk customs of Thrace and its Evros prefecture, Dimitris Vrachiologlou wrote that elderly women used to keep the icons company all night long, singing songs and psalms.

Outside, the priest blessed the young men who gathered around him in a semicircle. Then, as the bells tolled, they hefted the icons high over their heads and ran around the church shouting “Kyrie Eleison!” or “Lord have mercy!” Their cries grew louder each time they came into view, led by Christodoulos Tsiankas, who, dressed in jacket and tie, carried the cross.

This, I learned, was a position of great honor. Traditionally, the privilege was auctioned off each year, with the proceeds—in drachma or oil—going to the church. Nowadays, it’s passed from one household to another, but always to the right, never “backwards,” since that is considered bad luck. The cross and icons are carried only by young men: Angeliki’s older brother Christos, a border guard, ran with the cross in 2019; this year, her 17-year-old brother Marios held an icon depicting the baptism of Christ.

The men circled the church three times to consecrate the village and ward off mischief-making goblins called kallikántzaroi. In Greek, Bulgarian and Turkish folklore, kallikántzaroi live underground and surface during the 12 days between Christmas and Epiphany to wreak havoc. These small, black devils have blazing red eyes and long tails. They love to spoil meals, smash furniture and overturn pots and pans, but they are afraid of light, fire and holy water and can’t count to three because the number is linked to the Holy Trinity.

The English writer and philhellene Patrick Leigh Fermor believed kallikántzaroi evolved from satyrs and centaurs, ancient half-human hybrids. He said their name derived from the Greek words kalós kéntauros or “beautiful centaur” in accordance with the age-old precaution of placating a malicious or unpredictable force by calling it good.

In his book Mani, detailing his travels in the southern Peloponnese, Fermor wrote about the clear continuity between pagan and Christian religious practices. He argued that Greeks have always been polytheists, citing how ancient shrines and temples were rededicated to Christian saints who “assumed local spiritual sway and presided over the various fields of human activity in the same manner as the gods” of the Greek pantheon.

According to Ms. Angela, as I’ve come to know her, the Epiphany ritual in Dadia is rooted in ancient magic circles; villagers run around the church three times to protect it symbolically with the metaphysical force of Christ and the saints.

Indeed, when Dadia was smaller, men used to circle the entire village with their icons. As the village grew, the custom changed, and they ran on a predetermined route through the streets, circling each church and chapel three times in sun, rain, sleet or snow. Those who didn’t join the festivities at Agios Nikolaos would come out of their homes to greet the icons with incense, sometimes bringing their animals out as well.

Later, over coffee at the Forest Inn, Angeliki showed me a video of the 2014 celebration, when men carried as many as 50 or 60 icons through the village and hundreds of people from all over the region gathered to sing and dance in the church courtyard.

This year’s procession returned to the courtyard after completing its third circle around Agios Nikolaos. Villagers lowered their masks to kiss each of the icons as the men lined up to reenter the church. Meanwhile, women served refreshments brought by the families of the men who carried the cross this year and the year before. The former brought colorful candied chickpeas and cognac, the latter kólyva, a sweet mixture of boiled wheat, roasted sesame, flour, sugar and cookie crumbs. This dish, often served to commemorate the dead, was similar to the nutritious várvara I tried last month, and also featured wheat, one of the region’s most important crops, as its main ingredient.

Since dancing was not permitted this year and the priest usually leads the dance, we instead stood in a circle around Páter Ioakim while he led the congregation through the traditional Epiphany song, a prayer from the Virgin Mary to Saint John the Baptist. It begins:

Today, lights and illumination

and great joy and sanctification;

Today, our lady Panagia

holds the swaddled Christ at the spring

with censers on her fingers

and to Agios Ioannis beseeches,

‘Can you, Agios Ioannis Prodromos,

baptize the child of God?’

As I sipped cognac and listened to the congregation sing, I thought about how intimately the Church was tied to Greek people’s lives, especially in villages like Dadia. Every major life event, from baptisms to weddings and funerals, and every feast day that set the rhythm of the year occurred within the Church. Had the two-year pandemic disrupted this role?

* * *

I returned to Dadia two weeks later to observe the custom of the kourbáni, the ritual slaughter of roosters and rams for the January 18 feast day of Agios Athanasios, when for one day, everyone in the village eats the same meal. Animal sacrifice occurs throughout Thrace, another element of ancient worship that has been absorbed into regional Orthodox practice.

There was much uncertainty about whether the tradition would be held this year due to COVID-19. Angeliki’s brother Mario called her from school to say it was happening—he was excited to help with the slaughter. But when we arrived at the small church of Agios Athanasios where a group of men usually stayed up all night to cook the meal in large, cylindrical cauldrons, we found the kitchen empty and the cauldrons stacked away in corners.

Angeliki arranged for me to speak with Páter Ioakim after his evening liturgy. She warned me to mind the time because the friendly priest with the salt-and-pepper beard was known for his ability to talk. Afterward, we planned to feast at the local taverna I Foliά tou Pelargoú, “The Stork’s Nest,” where Angeliki had worked as a teenager. The taverna’s owner, Dimitra Mpampaka, is father-in-law to Georgios Porikos, who retrieved the cross from the Magazi River.

Our stomachs were already grumbling when we met the priest at the home of Sophia Giannakoudi, a 78-year-old widow of Bulgarian descent who lives across from Agios Athanasios and takes care of opening, cleaning and maintaining it. She had even received a blessing from the metropolitan of Didymoteicho, Orestiada and Soufli to enter the sanctuary of the church, a privilege usually reserved for men.

Yiayiá Sophia, as Angeliki called her, had lived alone for 22 years, but she still tends to her grapevines, and every Saturday, peels 20 to 30 kilos of potatoes and bakes bread for Taverna Simos, which her husband built and her daughter and son-in-law now run.

As the widow welcomed us into her home, I noticed most of the rooms were closed off behind screens of potted plants. The heart of the house was the kitchen and living room, kept warm by a wood-burning stove. The couch where Angeliki and I sat folded into a bed, and there was a small dining table with a woven table runner and a television set in one corner. As we talked, Yiayiá Sophia brought us water and homemade cheese pies. “Here, in Dadia, whichever house you visit, don’t be shy,” she told me. “We’re all the same!”

Páter Ioakim grew up in Athens’s port of Piraeus and served as a monk in the monastic community of Mount Athos for 18 years before coming to Dadia in 2015. “In Evros, we priests need to maintain our traditions to keep people’s spirits up,” he said. He emphasized the priest’s customary role in leading the big dance in the church courtyard during Epiphany and how everyone holding hands symbolized unity and strengthened community bonds. “The heart of the village is the church,” he said. “If the heart stops beating, it dies. If the bell of the church stops ringing, the village dies.”

The priest believed the presence of the Greek Orthodox Church was especially important in Evros because of the region’s strong Muslim influences. “We may be at the end of Greece, but we are also the beginning of Greece. It’s important that we ring the church bell because it can be heard across the border. Just as I wake up and hear the call to prayer from the other side, the Muslim hódjas (Turkish religious leaders) can hear my bell.”

Angeliki interrupted. “You just said that the church is the heart of the village, the beginning and the end. So, why aren’t we doing the kourbáni?” She was upset that the custom had been canceled for the second year in a row and worried that, after such a long gap, people might stop practicing it, might forget.

She also took issue with Páter Ioakim’s responses because she felt they focused only on priests and the Church while ignoring the role of the community. “The village needs to preserve its traditions, side by side with you,” she said.

* * *

Long before the birth of modern Greece, Orthodoxy was seen as a hallmark of national identity. The first Greek constitution of 1822 defines Greeks as “All the indigenous inhabitants of the Greek Territory who believe in Christ,” and subsequent constitutions recognize Greek Orthodoxy as the country’s “prevailing religion.”

While that may seem strange to American readers accustomed to the separation of church and state, the Greek Orthodox Church’s role reflects its history preserving Greek language and culture throughout centuries of Ottoman rule. It also played a leading role in the struggle for independence. As Mark Mazower writes in The Greek Revolution: 1821 and the Making of Modern Europe, the revolt “assumed at the outset the character of a religious clash” between Greek Orthodox Christians and Muslim Turks. Today, 90 percent of 1,465 surveyed Greeks identify as Orthodox, and three-quarters say that being Orthodox is important to being “truly Greek,” according to a 2017 Pew Research Center study.

One of Greece’s largest real estate owners, the Church retains close ties with the state. When six Rafale fighter jets purchased from France arrived at Tanagra Air Base last month, the metropolitan of Thebes and Livadeia blessed the aircraft and their pilots. The government treats priests as civil servants and pays their salaries, estimated at 200 million euros annually. In addition, religious instruction is part of the mandatory curricula for primary and secondary schools, although students may receive an exemption with parental consent.

Given its influence in society, the Church has been criticized for providing a powerful platform to divisive figures such as former Metropolitan Amvrosios of Kalavryta, who was convicted of hate speech and resigned in 2019. Amvrosios infamously supported the far-right, anti-immigrant Golden Dawn party and called on the faithful to “spit upon” LGBTQ people.

But publicly challenging the Church can be risky. This month, an Athens court convicted two human rights activists of “falsely accusing” Metropolitan Seraphim of Piraeus of antisemitic hate speech in 2017. The authorities dismissed the activists’ complaint against the bishop on the grounds that his statement was part of the doctrine of the Orthodox Christian Church.

Yet the Church’s sway among younger generations may be waning. In a 2020 survey, the research and policy institute Dianeosis found that 27 percent of 118 respondents aged 17 to 24 said they did not believe in God, and about 40 percent of the poll’s 1,250 total respondents reported not feeling close to religion. Many I spoke with, including Angeliki, also believed the wealthy Church could have done more to help people who suffered during the decade-long financial crisis.

Greece’s last, leftist government proposed measures to create a clearer distinction between church and state, but those plans were scrapped when the conservative New Democracy Party came to power in 2019.

And the pandemic has created new tensions between the Church and Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis’s government. Although Church leadership has largely supported public health measures, Orthodox hardliners have urged their congregations during weekly sermons not to get vaccinated and even refused entry to those wearing masks.

In October, a nurse in Alexandroupoli told me that most of the new cases he was seeing came from one such neighborhood church. He attributed Evros’s low vaccination rate to religion, social conservatism and lower education levels. As the omicron variant drove rising cases in the regional unit last month, the vaccination rate still lagged about 15 percentage points behind Athens’s.

Meanwhile, the virus has ravaged clergy members throughout Greece, many of whom were slow to get jabbed. Metropolitan Kosmas of Aetolia and Acarnania in western Greece died of COVID-19 last month after refusing the vaccine and vehemently criticizing government measures. “God does not allow you to be infected. God does not infect!” he said.

“There are voices that speak out alone,” Páter Ioakim said. “But the Church doesn’t say ‘Don’t shout, don’t speak.’ The Orthodox Church is democratic. We all say our opinions, and in the end, we all decide together whether something is right or wrong.”

The priest, who got his booster shot a few days before we met, also thought about not getting vaccinated, but when the metropolitan of Didymoteicho, Orestiada and Soufli got the jab, he followed suit to protect himself and others. He described how science and faith do similar work, caring for body and soul. “Could it be that God sent the pandemic to make us better people?” he asked me. “To show us that death is among us, that He is all-powerful and in one minute can destroy the whole world?”

Ms. Angela wrote on the Ethnological Museum’s Facebook page that the blessing of the water on Epiphany and throwing of the cross is a symbolic ritual of purification, rejuvenation and fertilization that teaches respect for the element essential to all life. The worship of water, the beginning of everything: the waters of the womb, the baptismal font and also the rivers, deified by the ancients, which feed the crops and now form the boundaries of Greek Thrace.

Like water, Orthodoxy has changed and adapted over the centuries in order to survive, and its impact is most clearly felt in the daily life of villages like Dadia and in varied customs like the kourbáni and the burning of a Judas effigy in village and town squares at Easter.

Village hospitality, too, seems to flow without stopping. It envelops and nurtures; it gives life. The villagers of Thrace pride themselves on an authentic kindness that is difficult to find today. “They don’t seek to profit from you,” Ms. Angela told me.

Gazing at the setting sun through the pine trees with Angeliki, I gave thanks for my new friend and looked forward to our next adventure together.

Top photo: At the end of Epiphany, mask-wearing villagers return the icon of Panagia to the Monastery of Dadia. As part of the ceremony, they run three times around the monastery’s main church