AMAXADES, Greece — The man who pulled me over at sunset on Greek Independence Day in March drove an unmarked gray van and wore black pants and a black hoodie. Blocking my path on a desolate strip of farmland near the Kosynthos River in Thrace’s Rhodope prefecture, he motioned for me to turn off the car. He was in his late 40s or early 50s, clean shaven with dark hair. He approached the driver’s side door with a handgun drawn.

An embroidered patch stitched to his chest depicted a skull wearing a Spartan helmet emblazoned with the Greek flag. The skull, the logo of Marvel’s antihero The Punisher, was a symbol of vigilante justice that has been appropriated by police officers, soldiers, militants and far-right groups around the world, including the January 6 Capitol rioters.

The man asked for my ID and snatched my phone from my hand. I’d been pulled over before by officers who had asked for identification, but they had always shown me their badges and acted procedurally. Was this man with the police? Was he robbing me? Trying to remain calm, I removed my ICWA cap so he could see my face.

He took a phone out of his messenger bag, accidentally dropping his gun on the ground near the front of my car. I watched him bend over to pick it up. He read my license plate number to a colleague on the phone. He told me to step out of the car and empty my pockets onto the dusty hood, where he had placed my phone and residence permit. The sun had turned red and was beginning to set.

“What are you doing here?” he asked.

I said in Greek that I’d spent the day hiking the Strait of Nestos, a four-hour path along the winding, green Nestos River that forms the western boundary of Thrace. When he stopped me, I’d been looking for the archaeological site of Anastasioupolis before heading home to the port city of Alexandroupoli.

He found it strange that I was out searching for archaeological sites, especially at this time of day. I agreed, trying to smile. He gestured to my boots, my hoodie and jeans. “You were hiking in those shoes? Those clothes?” he asked, unsmiling. “Are you messing with me? What are you really doing here?”

I told him I wrote monthly articles about Greece, that it was my job to explore and talk with locals. I had taught at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, I said, and I used to work for the US Embassy. I answered questions about my car, where it was from and how much I paid to rent it.

He asked me to open my glove compartment, the trunk and all the car doors. Passing over the Turkish sweets I’d picked up in the town of Xanthi, he looked inside my camera bag and examined my tote, touching the thick slices of bread I’d wrapped in napkins from lunch, the bag of dried chickpeas and raisins I’d brought with me on the hike. He took a receipt from the passenger’s seat and studied it for a long time in the fading light, then folded and returned it.

“You know, we have a big problem with illegal immigrants,” he said. “You shouldn’t be wandering around here, especially after sunset. It’s dangerous. They could steal your car.”

When he spoke to his colleague again, he called me palikári, a word in Greek that refers warmly to a young man, and told him he wasn’t needed, all was well. Standing beside my car in the evening chill, I let my breath out. The sun had set behind the fields and tiny mosquitoes landed on the roof. I collected my lip balm and change, phone and pen.

But the incident shook me, and later I wished I had asked the man for his own credentials. I knew the encounter—being intercepted by an unidentified man in an unmarked van, often based on racial profiling, and having my phone and identification documents taken away—fit the first step in what human rights organizations, journalists and civil society describe as a long-standing, systematic state policy of “pushbacks,” the secret and illegal apprehension, detention and expulsion of migrants from Greek territory without granting them access to asylum procedures.

As Greece fortifies its land border with Turkey in the wake of the 2020 crisis I wrote about in my last dispatch, Greeks who work with and advocate for asylum seekers in the region are painting a stark picture about the costs of militarizing Europe’s borders. Alleged pushbacks not only endanger migrants and refugees’ lives, they say, but also have larger repercussions for transparency and rule of law in Greece, and for the country’s international reputation.

Reports of systematic pushbacks at the Evros border

The UN refugee agency has documented almost 540 reports of pushback or refoulement by Greece since the start of 2020. The issue continues to bring Greece negative press, although stories of pushbacks are underreported by local media. Last December, the European Court of Human Rights announced it would examine 32 cases filed against Greece for the illegal expulsion of migrants from its territory. Many of these recurring, consistent reports allegedly occurred in Evros, this eastern region that has been called “the back door to Europe.”

In early February, 19 migrants froze to death in a field just inside the Turkish border, a grim two-year high for casualties in a single incident. Some were found wearing only shorts and t-shirts at a time of year when nighttime temperatures can fall below zero degrees Celsius. Officials claim the victims never reached Greek soil, but four survivors say Greek border guards pushed them back in the middle of the night, stripping them of their warm clothes and shoes.

And last month, for the first time ever, the European Court of Human Rights issued an interim measure in Evros, ordering the Greek authorities to rescue 30 Syrians who had been stranded on an islet in the Evros River for five days in life-threatening conditions. The group also says it was pushed back to the islet from Greece, which resulted in the death of a four-year-old boy.

Officials deny any wrongdoing and largely refuse to investigate the reports. Chrysovalantis Gialamas, president of the Association of Border Guards of Evros, called the allegations “clearly Turkish propaganda” and nothing more, repeating Greece’s commitment to international law. “We condemn every form of violence, and we condemn every form of fake news, which is mostly published by our neighboring country,” he said. “I’m on the Evros River every day with my colleagues. As border guards, we have shown our humanity countless times.”

“Real refugees” vs. “illegal immigrants”

Many Evros locals maintain a strict distinction between migrants and refugees. As an electrical engineer named Sardanis Zisis drove along the 12-kilometer steel fence separating Greece and Turkey, he described the conceptual divide between refugees and lathrometanástes, a compound word I hadn’t heard before. It was a pejorative term for “illegal immigrants,” the prefix lathro- referring to something done illegally or in secret.

“Most of us were refugees who came here from Turkey,” Zisis told me. “That’s why we feel solidarity with refugees. Everyone wants to help a refugee. But an illegal immigrant, you can’t help him. He’s illegal. A refugee comes from a war-torn area. He’s lost his home, his family, his property. And he must leave so he won’t be killed. International law stipulates that refugees need help. But illegal immigrants? I don’t think so. That’s something completely different.”

The question of who is and who isn’t a refugee has been debated in Greece for years. In a March speech on Greece’s readiness to welcome “real refugees” from Ukraine, Migration and Asylum Minister Notis Mitaraki noted that the authorities had rejected 70 percent of asylum applications in 2021. “So seven out of 10 who crossed our borders illegally, based on the decisions of this country and international law, are not refugees,” he concluded.

But the current government has actively limited eligibility for asylum by designating Turkey a “safe third country” for nationals from Syria, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Somalia, who make up roughly 60 percent of applicants. That decision, in line with a 2016 EU-Turkey statement designed to slow migration flows through Greece, has been denounced by 40 NGOs, which argue that it undermines migrant protections by forcing external countries to assume obligations Europe is supposed to honor.

As a frontline state, Greece bears a greater burden in dealing with migrant flows than many of its EU partners. In villages like Nea Vyssa, everyone can remember a time when they offered asylum seekers croissants and snacks, or even let them warm breast milk to feed their babies. “For years now, as I and my grandparents remember, migrants have always crossed the border, and we’ve stopped to help them,” said Eleni Baharidou, president of Nea Vyssa’s civil volunteer group. “But that doesn’t mean we can accept them and host them here forever.”

Reports of migrants stealing food and cars have also hardened local attitudes in a region previously unaccustomed to crime. One resident told me the villagers had nothing against people who were different, but when they stole, it automatically made them enemies.

The 2020 border crisis, prompted when Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan pushed thousands of Afghan, Iranian, Iraqi, Bangladeshi, Pakistani and Syrian asylum seekers to the Evros land border, further entrenched this view. Migrants attempting to pass into Europe were seen as “tools,” “weapons” and even Turkish agents in what Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis later called a “hybrid threat for Europe.” NGOs like HumanRights360 have warned that kind of language dehumanizes asylum seekers, increasing the likelihood of human rights violations.

Monitoring migrant flows and illegal practices

Akis Maragkozakis, a social worker for HumanRights360, is one of my closest friends in Evros. He’s introverted and athletic, a good listener, a lover of books and the outdoors. We hike together with his friends around Avantas, a village north of Alexandroupoli, and study side by side at a bookstore café in town.

Like many Greeks in Evros, Akis’s grandparents came to Alexandroupoli after the Asia Minor Catastrophe in 1922 when Turkish forces captured and reportedly burned the city of Smyrna. “I remember stories my grandfather told me, how he left his home near Smyrna and came here as a refugee,” Akis said. “My grandmother died of sorrow, she was so sad to leave her home.” Akis identifies with those who seek to cross the border because his family arrived the same way. “Why does it bother us now that people come and ask for help? Because they have a different religion? Why is that important when they’re coming to save their lives, like we did?”

Akis provides legal aid and psychosocial support to unaccompanied and separated minors at the closed migrant Reception and Identification Center in the village of Fylakio, Evros. Since May 2020, he has also monitored migrant flows and reports of illegal practices on the Greek-Turkish land border.

He told me pushbacks in Greece are not new but have become more organized and reached a peak since the Evros border crisis. He said the events of 2020 confused two separate issues: people seeking safety and the political tensions between Turkey and the European Union. So when people come to Greece seeking asylum, the average local sees them as a threat from Turkey and supports pushbacks to prevent Turkey from messing with Greece.

That the government’s suspension of asylum procedures and immediate deportation of migrants during the crisis went virtually unchallenged by European leaders contributed to a climate of impunity. Indeed, pushbacks and violence against asylum seekers have been reported across Europe’s external borders, in Poland, Italy, Spain, Croatia and Romania.

While the conservative New Democracy government touts its success in staunching migrant flows—a 90 percent reduction since 2019, according to Mitaraki—Akis and others in human rights advocacy believe the figures implicitly confirm Greece’s policy of deterrence. “They say they’ve reduced flows,” he said. “Of course if a person comes to Greece and you push him back, you’ve reduced flows by not allowing him to come in. But it’s not that he no longer needs asylum. The need still exists, but you’ve violated his right to come and ask for protection.”

Bringing migrants’ testimonies to life

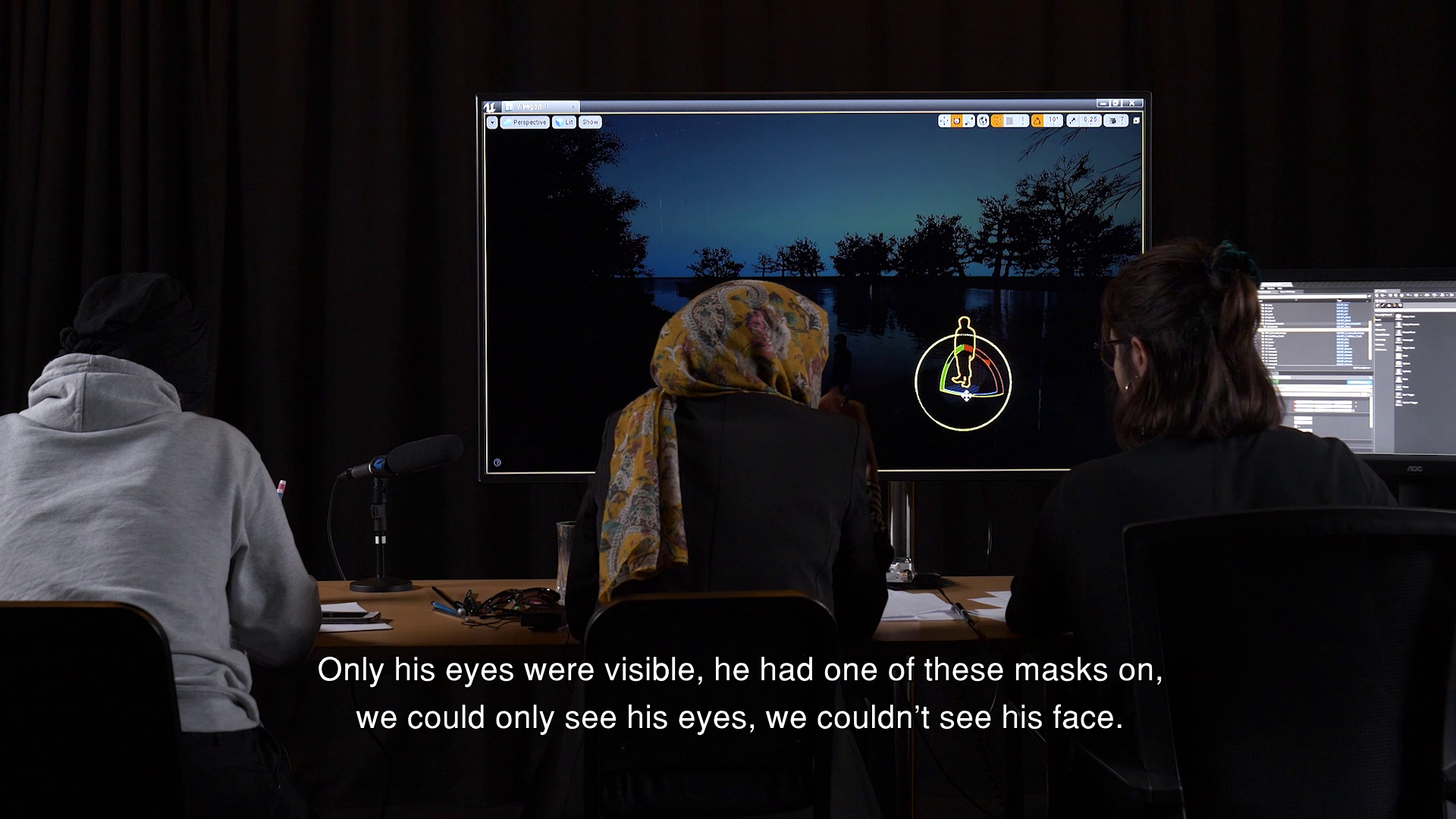

Akis put me in touch with Stefanos Levidis, an advanced researcher at Forensic Architecture, an agency based at Goldsmiths University in London. An Athens native, Levidis oversees the agency’s work on borders and migration, and has led several projects in collaboration with HumanRights360 to document human rights violations in Evros. “We knew pushbacks were happening for quite some time, but we didn’t have any evidence beyond human testimony,” he told me over the phone.

Because the Evros land border is a highly militarized, restricted area, it is extremely difficult for journalists, civil society and other watchdog groups to access the region, enabling officers to act with impunity. I observed that firsthand in February as I tried again and again to visit the border fence. Pushback victims routinely describe having their phones and papers confiscated or thrown into the river, a procedure seemingly designed to prevent documentation of the practice. Journalists investigating pushbacks and NGO workers on islands like Lesvos have been threatened and even prosecuted with espionage and smuggling charges for aiding migrants.

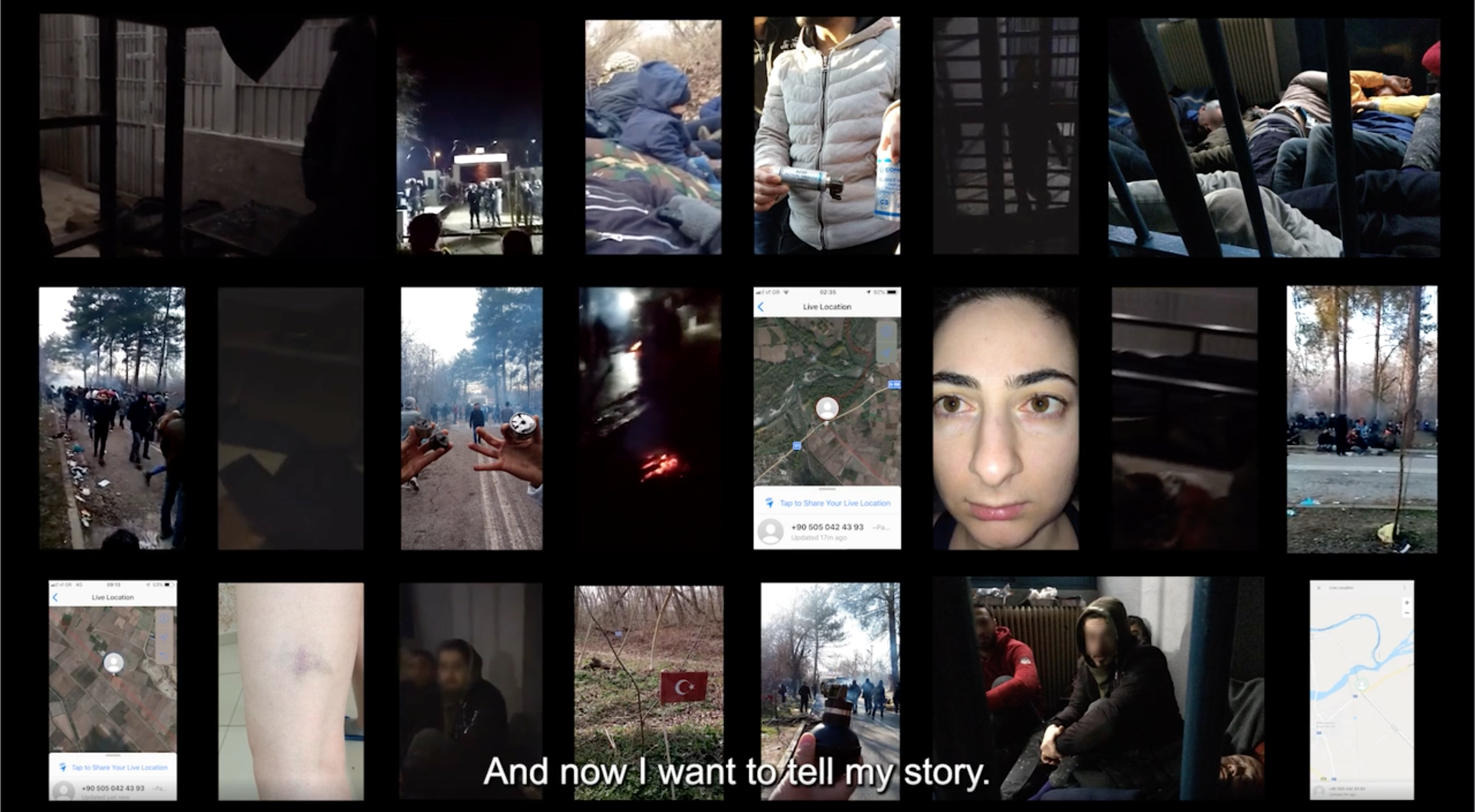

Levidis and his team eventually found the evidence they were looking for: in the first half of 2020, an Iranian woman named Parvin A. crossed the Greek-Turkish border seven times, seeking asylum in the EU. She was pushed back to Turkey six times before arriving safely in Germany in the summer of 2020.

During her first three crossings, Parvin managed to keep her phone. She shared her location with friends when she crossed into Greek territory and was detained in several border guard stations. She filmed herself in crowded, dirty cells and documented the injuries she sustained in detention. During her second pushback, Parvin was apprehended near the Iasmos toll station, not far from where I was stopped. Her third pushback on February 28, 2020 coincided with the crisis at the Kastanies/Pazarkule border checkpoint.

“I promised myself during one of the pushbacks that when I get to Europe, I will go to the court and get some justice,” Parvin said in a recorded statement. “Because this pushback, this violence has to stop. We are human beings, and I want to help get back some respect for human rights.”

Levidis and his team worked with Parvin to reconstruct her journey. They combined digital evidence with satellite imagery and a proprietary interview technique called “situated testimony,” creating 3D models to bring her memories to life.

Her experience corroborates countless witness testimonies of pushbacks at the Evros land border documented by human rights organizations since at least 2008. According to a European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR) report, the operations share a distinct modus operandi: people are intercepted, their belongings are seized and they are detained for hours without communication, information, food or water. At no point are they given the opportunity to apply for asylum. Often, they are tortured or beaten. At night, they are taken to the Evros River by armed men in black army gear and full face masks whom many witnesses call “commandos.” They are forced onto inflatable boats often driven by third-country nationals and left on Turkish banks or stranded on islets.

Migrants are usually pushed back within 24 hours after they have been apprehended. Last year, the Greek government ombudsman reported that complainants are “invariably convinced” the practice involves “state agencies and state agents at the levels of operational planning, logistics and perpetrators” betraying the existence of what Levidis calls “an unofficial migration management policy.”

Parvin and others have also reported hearing officers speak in German, raising serious questions about the involvement of Frontex, the European border and coast guard agency, in pushback operations. When asked to comment, the Frontex press team responded by email, “Frontex is not involved in pushbacks. Frontex is fully committed to uphold the highest standards of border control within our operations, and pushbacks are illegal under international law.”

Troubling new trends have emerged since 2020. People are now allegedly being apprehended and pushed back from cities like Thessaloniki and Athens, deep within the Greek mainland. A registered asylum holder with a valid German residence permit and passport and a French citizen claim to have been pushed back, demonstrating the process may be becoming increasingly indiscriminate.

In February, Parvin filed a complaint at the UN Human Rights Committee over multiple violations of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, including the exposure of an asylum seeker to danger and possible death. Forensic Architecture is supporting her case, and its work was submitted as evidence for the 32 cases filed at the European Court of Human Rights.

Why should Greeks be concerned about pushbacks in Evros? “For a number of reasons,” Levidis said. First, for their own interests because the borders are a testing ground for state coercion practices that are then applied in urban centers. He noted that police forces who responded to the 2020 crisis were later deployed in Athens and other Greek cities, where they responded brutally to demonstrators.

Second, and most important for him, Greeks should be concerned about repeated human rights violations within their borders. “As a Greek, I am personally ashamed and angered by what’s happening, and I think other people should be as well. The scale at which this thing is taking place is horrific, and it will not be forgotten by history,” Levidis said. “I think we have a duty to make sure people are treated in a humane manner at our borders because the borders are a mirror, if you will, for the society they are enclosing.”

A final resting place in Europe

Just outside the Muslim village of Sidiro in central Evros, a former mufti named Mehmet Serif Damadoglou let me in to the gated hilltop cemetery where the Greek state buries migrants who have died crossing the Evros border. Unlike the small cemeteries filled with marble crosses I passed on my drive, the graves here were marked by blank, oblong stones that glowed gold in the setting sun.

It was a peaceful, melancholy place. Damadoglou said a prayer for the dead as the wind blew his robes around him. “Each time I came here to bury someone, I would say, ‘Today will be the last,’” he told me. “But still it continues.” As mufti, he had washed, wrapped, blessed and buried many of the bodies here. “Everything we do for our mothers or fathers, we do for them,” he told me. “We don’t discriminate because they’re migrants. No, they’re Muslims, they’re our brothers and sisters. There’s no separation.”

The cemetery was started in the year 2000 and now has more inhabitants than the village. Here, in numbered graves, lie some 500 young people from Syria, Iran, Palestine, Pakistan, Somalia and other countries who no doubt dreamed of a better life in Europe.

Pushbacks aren’t the only danger migrants face crossing the Evros River. According to Dr. Pavlos Pavlidis, medical examiner at the University Hospital of Alexandroupoli, drowning is the number-one cause of death for migrants, followed by hypothermia and vehicular accidents. Pavlidis performs an autopsy on each body to determine the cause of death and then tries to identify them. In the past two years, the number of dead has increased to around 50 annually. Most of the bodies he sees now are men between 18 and 30 years old.

The migrants buried in Sidiro make up the roughly 40 percent who could not be identified or whose families could not afford to bring their loved ones home. As I followed Damadoglou around the cemetery, he pointed out the grave of a Christian woman whose tombstone was painted with a small blue cross; a woman from Iran whose grave was marked by a cypress tree; and a young man from Aleppo whose family had sent money to engrave a marble tombstone. He’d been born in 1983, two years before I was, and died in 2014. Toward the back of the cemetery were fresh graves that didn’t have stones yet.

The writer and former publisher Giannis Laskarakis, also the son of refugees from Asia Minor, imagines another future for these migrants. He told me that when his family came to Greece, Greek people called them Turks and wanted to cast them out. But refugees brought life to the region. They developed the land, made money, created jobs. And now history is repeating itself.

“Greece needs people,” Laskarakis told me. “Every year, our population decreases. People are getting older, and there’s no one to work in the fields. Simple logic says, let migrants come here to study, to learn Greek, to become Greek. The ancient Greeks said you become Greek by learning the language, from a Greek education.” The same way that one becomes American, I thought.

The story of 17-year-old refugee Saidu Kamara lends credence to this view. Kamara came to Greece from Guinea as an unaccompanied minor, rose to the top of his class in the Athenian suburb of Agios Dimitrios and earned the distinction of carrying the Greek flag during his school’s independence day parade. Although he was set to be deported from Greece after his asylum application was rejected in December, his adopted country has rallied behind him, and an appeal is now pending.

The story has been very different for Ukrainian refugees. To date, Greece has welcomed nearly 15,000 of them with open arms. Reporters and aid workers have noted a double standard between the protection Greece and more broadly Europe offers to white, Christian refugees and its inhumane treatment of refugees of color.

Although I’ve lived and worked in Greece for years and speak Greek well, I will always stick out as a foreigner in this country. The fear I felt having a gun pointed at me by an unknown man and the suspicion I fought to dispel are just a fraction of the intimidation, violence and dehumanizing treatment pushback victims from the Middle East and Africa report having endured. I can only imagine the lasting physical and psychological trauma the practice inflicts.

I stand with Damadoglou, watching the sun set over the migrant cemetery. The former mufti continues to tend to the graves, insisting that a person deserves dignity and respect even after death. The Greek government paid to give these migrants a final resting place in Europe. What if instead they had been allowed to start a new life in one of the many abandoned and shrinking villages I’ve visited in Evros? Perhaps Ukraine’s refugees will give Greece an opportunity to rethink its policy toward all asylum seekers and envision a future that harnesses their resilience and dynamism to create a better future for the country.

Top photo: A refugee camp in northern Greece in August 2016