CHIOS, Greece — Toward the end of the tourism season, I sat amid a large crowd in the square of Chios castle listening to Notis Mitarachi, Greek Minister of Migration and Asylum and elected member of parliament for Chios, deliver opening remarks at “Colors of Another Era,” a polished performance of music, poetry and traditional costumes. Organized by the North Aegean Region with support from the Culture Ministry and Greek Tourism Organization, the event inaugurated a three-day festival celebrating the island’s medieval history.

Mitarachi, who was appointed in January 2020 when the conservative New Democracy government came to power, visited Chios frequently while I was living there. He had promised to boost the island’s economy, develop tourism and complete key infrastructure projects. He also pledged a firmer hand in dealing with the migration crisis that has burdened northeastern Aegean islands like Chios, Lesvos and Samos since 2015, when some 850,000 asylum seekers came to Greece from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan, seeking onward destinations in Europe.

Over the past three years, Mitarachi has increased fortification and surveillance of Greece’s borders, sped up the asylum procedure and decongested hotspot islands—measures supported by a majority of locals. On the other hand, he also insists on a distinction between “real refugees,” like the 100,000 Ukrainians fleeing war Greece has hosted so far, and “illegal immigrants” from the Middle East and Africa, who receive far less dignified treatment. In June 2021, Greece limited eligibility for asylum by designating Turkey a “safe third country” for nationals from Syria, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Somalia. But since Turkey stopped accepting the return of rejected applicants in March 2020, many have been stuck in legal limbo.

And while Mitarachi confirms that over 154,000 migrants were prevented from entering Greece in 2022, the government consistently denies engaging in pushbacks, the illegal apprehension, detention and expulsion of migrants from Greek territory without granting them access to asylum procedures. However, Greece’s long-standing, systematic state policy of pushbacks has been well documented by journalists and human rights groups. Indeed, a 2022 report by the human rights chief of Frontex, the European Union border agency, recommended suspending operations in Greece due to “credible reports” of continued abuses.

Chios, Greece’s fifth-largest island and Mitarachi’s constituency, currently hosts some 400 asylum seekers compared to 2,300 and 900 on Lesvos and Samos, respectively. For the most part, they are kept out of sight at the isolated Vial reception center. As Vial’s population dwindles, so has funding for the NGOs that support them. At the same time, government control and intimidation is contributing to an environment increasingly hostile to aid workers.

I spoke with several on Chios in December 2022 to learn how the refugee situation has evolved over the past eight years and what challenges they now face. With attention and resources diverted due to recession and war in Ukraine, these small, tenacious NGOs are committed to serving and advocating on behalf of the island’s asylum seekers for as long as they can.

The refugee situation in 2017 and 2020

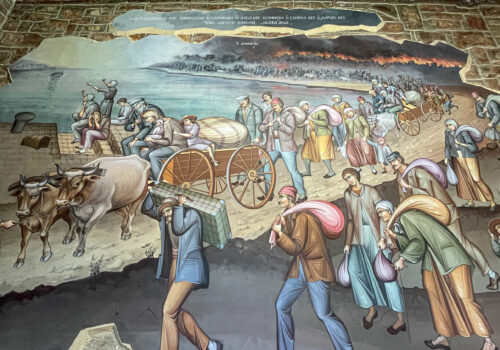

The refugee situation on Chios has changed dramatically since the outbreak of the crisis in 2015. In the summer of 2017, while walking along the castle walls not far from where I heard Mitarachi speak, I stumbled upon the Souda open reception facility, an encampment of white tents in the castle moat below me. Later, while researching the 1922 Asia Minor Catastrophe, I learned that a century ago, refugees from Anatolia had also settled in the moat. Then, as now, Chios hosted thousands fleeing west, and even though they were Orthodox Greeks back then, they were also discriminated against, called tourkósporoi or “Turk-spawn” by frustrated locals.

Although island residents initially welcomed refugees fleeing from Syria in 2015, the strain of hosting thousands of people soured the majority opinion as the crisis dragged on and Greece struggled to recover from its decade-long financial crisis. Petty theft and decreasing tourism to hotspot islands compounded resentments. “I have nothing against these people,” one local told me, “but they don’t try to assimilate, and they have a different religion.” In 2020, Chios residents requested 428,000 euros in compensation for damages made by asylum seekers at Vial.

Souda, the smaller of two Chian camps, was run by the municipality and UNHCR. It operated from 2015 to 2017 and housed approximately 700 refugees in March 2017. Many had been stuck in the overcrowded site for seven months or more, unable to leave Chios until their asylum claims were processed. Several times, far-right extremists attacked the camp, throwing rocks and Molotov cocktails onto tents from above. When Souda closed, its inhabitants moved to the larger Vial camp, 8 kilometers from town on the site of a former factory near the village of Chalkeios.

In September 2020, while visiting Chios to prepare my ICWA fellowship application, I drove by Vial for the first time. At that point, the camp held some 3,800 asylum seekers, over three times its capacity. A jungle of makeshift tents had grown up around the camp with poor sanitation and exposure to the elements. Inhabitants frequently protested the inhuman conditions, especially as Covid cases rose. Three weeks earlier, a Yemeni man in Vial had tested positive for Covid, the first known case in Greece’s island camps, and it was placed under full lockdown.

The fields surrounding the camp were strewn with garbage. People milled about in the oppressive noon heat. I stopped behind a truck delivering potable water and watched a little girl drag two jugs across the dirt road. A man sitting on a tree stump waved to me as I passed. Further off, red taxis waited for fares in the shade of an olive grove. The camp’s distance from town, almost a two-hour walk each way, makes it difficult for asylum seekers to access services.

In response, NGOs like Action for Education, METAdrasi and Chios Eastern Shore Response Team set up free shops and education centers within walking distance of Vial. I had the chance to visit Action for Education’s Mastic Campus, a warehouse that had been lovingly converted into classrooms, a computer lab and recreation area for refugees aged 18-23. The campus also offered hygiene services, a kitchen, laundry machines and showers. Outside in a large yard with shaded benches and soccer goalposts, cucumbers and eggplants grew in a sandbox garden.

Action for Education also ran a youth center in Chios town with funding from the Stavros Niarchos Foundation, and it was opening a new center called the HUB where asylum seekers could learn languages and develop new skills.

Solange Würsten, then-director of the Swiss organization on Chios and Samos, came to the islands because she wanted to see the situation for herself and take responsibility for what the European Union was not. She told me Vial’s location prevented asylum seekers from integrating into the community, and that she believed a law requiring NGOs to register was intended to shut them down, part of the government’s overall crackdown on migrants and refugees.

“They don’t want us here,” she told me. “There’s a lot of misinformation about where our money comes from and lots of conspiracy theories. The number one statement people make is that we’re puppets of George Soros.”

The day I left Chios, fires destroyed the infamous Moria camp on Lesvos, which in early 2020 held nearly 20,000 people, seven times its official capacity. Six asylum seekers, known as the Moria 6, were arrested for starting the fires, though analysis by the research agency Forensic Architecture disputes the evidence against them and uncovers a recurring pattern of fires left unaddressed by the authorities. The trial of the Moria 6 has been postponed to March 2024.

Meanwhile, the government has built EU-funded Closed Controlled Access Centers (CCAC) to house asylum seekers on Samos, Leros and Kos. Mitarachi announced that new facilities will also open on Lesvos and Chios this year despite islanders’ attempts to block the delivery of construction material. NGOs have decried the remote, “prison-like” detention centers, claiming that the camps’ 24/7 security and CCTV, biometric entry points and double layers of barbed-wire fencing exacerbate asylum seekers’ psychological distress.

The refugee situation in late 2022

When I returned to Chios in the summer of 2022, I was saddened to see the storefront of Action for Education’s former youth center completely empty, a yellow “For Rent” sign stuck on the dusty glass. The day I visited the center with Solange, young asylum seekers were painting black triangles on the façade to mimic the distinctive geometric patterns called xystá etched onto buildings in the mastic village of Pyrgi.

In February 2022, after four years on Chios, Action for Education closed its operations and left the island “with a very heavy heart.” As a result of Covid restrictions and faster asylum processing, beneficiaries had less opportunity to access educational services on the island. The NGO decided to shift its focus to mainland Greece, opening a safe space for families with young children called The Nest in Athens. The now-vacant space reminded me how fluid the migrant situation remains even eight years later.

While guiding a German delegation through a clean Vial in March, Mitarachi tweeted that the camp’s population has dropped from 7,000 to 350, and the government returned 50 stremma (5 hectares) of surrounding land to the local community. But the decongestion comes at the expense of what many NGOs have called the government’s “criminalization” of migrants, policies that punish asylum seekers with degrading, often life-threatening treatment, shirking EU obligations.

During my stay, arrivals mostly came from Somalia, Eritrea and Palestine. They frequently hid in the island’s interior for days after landing, fearing they’d be apprehended by the authorities and pushed back. Anastasios Fousianis, a nurse at Vial, told me that they came to the camp in small groups, often dehydrated with no clothes or food.

In July, a Somalian woman died of hunger and thirst in the mountains near the northern shipping village of Kardamyla, and in December, Christos Michalios, a retired Kardamylan sea captain, reported finding 13 Somalis around 17 to 18 years old, one of whom had suffered a heart attack. “He didn’t have a pulse at all,” said Michalios, who managed to revive him with first aid. “If I hadn’t gone out for a cigarette, he would’ve died.” He blamed Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan for manipulating refugee flows to blackmail Europe. “It’s shameful to utilize these people’s pain and difficulties for political ends,” he said.

Vial’s reduced staff is unprepared for influxes in new arrivals. Fousianis, who worked in a camp laboratory performing blood and urine tests, Covid tests, Mantoux tests for tuberculosis and dermatology checkups, watched his team shrink from four employees to just himself and another working part-time. When we spoke in early December, his appointment calendar was fully booked through the end of January. “My job has been very difficult,” he said. “There’s not enough staff and not enough organizations. The ministry of migration is trying to cover all the immigrants’ needs without involving NGOs, but they’re not yet ready to do this.”

As the Covid pandemic waned, the end of 2022 saw an increase in arrivals, including a notable rise in unaccompanied minors. Fousianis estimated there were about 120 on the island when we spoke. The Greek NGO METAdrasi, which won the 2 million dollar Hilton humanitarian prize in 2019, runs a Transit Accommodation Facility for these children on Chios. The shelter, which opened in 2016, has a capacity of 20, giving priority to the most vulnerable. In December, it was completely full, and even the two beds reserved for Covid cases were occupied.

Vasilis Lilitsoglou, manager of the METAdrasi shelter, is a big guy with smiling eyes and a thick black beard. When we met in 2020, he reminded me of Hagrid from Harry Potter, funny, empathetic and fiercely protective of his charges. “It’s very difficult for a Greek family to understand how parents could send their children off alone,” he told me then. “They only do it because the sea is safer than the land.”

When I returned in July 2022, Lilitsoglou seemed more frustrated with the situation on the ground. Five of his 17-year-old charges would soon be transferred to Supported Independent Living (SIL) apartments. However, the housing program for young adults over 18 had been cut, so asylum seekers who benefited from METAdrasi’s accommodations were sent to camps on the mainland if still awaiting a decision when they turned 18. If granted asylum, they received a travel document, residence and work permit and were no longer eligible to live in the camps.

The futility of the situation left Lilitsoglou questioning his purpose. “You’re dropping them in the sea and saying ‘swim,’” he fumed. “They have to find work, but no one will take them. Language is the first barrier. And there’s so much they need to learn about Greek life. All this shows that we don’t want these people to be part of our society, our future.”

During the summer, 11 young adults from Greek America Corps, the volunteer program of the Greek America Foundation, spent three weeks at the shelter teaching English, playing sports and board games and organizing activities like beach clean-ups with the kids. “This experience gives our North American volunteers a different perspective about the world around them, which they keep close to their hearts for the rest of their lives,” said Greece Program Director Eleni Anagnostopoulos. Lilitsoglou found the group “very helpful, open-minded and open-hearted.”

Pothiti “Toula” Kitromilidi, a headstrong woman from the village of Megas Limnionas, joined the aid effort in 2015 when she heard the cries of children landing on the beach near her home. She runs Offene Arme (“Open Arms” in German), formerly Chios Eastern Shore Response Team, the only homegrown NGO remaining on the island. It provides essential non-food items to refugees like landing packs for new arrivals, personal hygiene kits and skin infection packs for people suffering from scabies. The NGO makes bimonthly distributions outside Vial and runs a free shop out of its warehouse in Kampos where people can select shoes and winter clothes.

Toula collaborates with other organizations on the island and also sends supplies to Leros and Kos. Lighting a cigarette outside the shop, the seasoned aid worker seemed weary. “We thought the situation would be resolved at some point, that the governments would take responsibility,” she said. “But seven years later, my friend, this hasn’t happened.”

The instability of the past few years has made it difficult to keep operations going. Brexit was the biggest problem, since 60 percent of donations used to come from the United Kingdom, but the customs fees required to import them have become prohibitive, and Offene Arme must now buy “an enormous amount” of supplies itself. During Covid, less volunteers were able to come to Chios, and many NGOs left the island, redirecting their efforts to Ukraine.

Toula had planned to shutter Offene Arme last October, but at the last minute found funding for the first three months of 2023, and is raising funds to cover the rest of the year. “We will try until the end,” she said. “I believe in this team and in this cause. For seven years, we’ve always managed to find a solution, and I believe we will again. As long as the need is here.”

While visiting Offene Arme, I also spoke with several young volunteers. Matthias Di Christine from Berlin worked in the warehouse for three weeks and was impressed by both the highly qualified volunteers and volume of material the NGO distributed. “On Monday or Tuesday, there were almost 40 people here,” he told me. “Each of them gets 25 items, so that means 1,000 pieces of clothing went through the shop and warehouse. It’s a huge logistical undertaking.”

Margaux Gruaz had worked for the UNHCR in Geneva and wanted to gain field experience. She spent four months working as warehouse coordinator, doing inventory and making sure the most essential items—underwear, joggers, jackets and shoes—were always in stock. Francis Di Gallo from Basel, Switzerland, had previously worked on Chios as a language teacher and social worker at Action for Education. After volunteering in the free shop for 15 months, he had applied to work at a shelter for unaccompanied minors in Basel.

A sense of duty and a desire to act also drives Ruhi Loren Akhtar, founder and CEO of the British NGO Refugee Biriyani and Bananas. She has been involved in refugee aid since 2015, when she and a group of friends provided 2,500 portions of biriyani and bananas to all the residents of the Dunkirk refugee camp in northern France. She started working on Chios in 2017 because she felt that compared to Lesvos and Samos, the island wasn’t in the media as much and there weren’t as many volunteers and aid organizations. “It’s more difficult for people to access services on the island, and I just felt Chios needed more support,” she said.

Akhtar has streamlined the organization for flexibility and adaptability. She recently moved the team to Athens, but they return to Chios every 4 to 6 weeks to distribute food and hygiene products outside Vial and in apartments as far down as Nenita in southern Chios, where migrants work the mastic trees. In March, the team delivered culturally appropriate Ramadan food packs. It also supports asylum seekers remotely with a help line number and can send staff from Athens if communities need immediate assistance. Last summer, for example, Akhtar’s team repatriated the remains of the woman who had died of starvation after hiding in the mountains.

Akhtar, whose parents are Bangladeshi, manages a diverse team, including people with lived experience of displacement from Syria, Yemen, Afghanistan, Palestine, West Africa and Somalia. She says she believes in working very closely with the community she serves and assessing their needs through frequent outreach. The NGO also works to build trust with asylum seekers and raise awareness about the ongoing humanitarian crisis. “Greece isn’t in the media so much, but people are hungry, they’re going through the trash to feed themselves,” she said.

Refugee Biriyani and Bananas is one of the few organizations that post about pushbacks. “A lot of people don’t speak about them because they’re scared of criminalization,” Akhtar said. “There’s a lot of hostility toward aid workers and NGOs in general. Often we’ll get stopped or questioned, or intimidation tactics are used. If you’re brown and wearing a headscarf, it’s even more apparent sometimes. But we keep going for the sake of the people.”

Tommy Olsen, founder of the Norwegian watchdog organization Aegean Boat Report, also faces intimidation from the Greek government. Olsen, who volunteered on Lesvos from 2015 to 2020, launched a website to track migrant arrivals, camp populations and pushbacks on Greek islands. He compiles information from the Greek and Turkish authorities as well as asylum seekers who have arrived on Greek soil. He has clearly documented pushback cases from Chios, Lesvos and Crete and has corroborated stories in The New York Times, The Guardian and Der Spiegel.

“You probably are aware of all the accusations from Greek authorities when it comes to me being everything from a smuggler to a spy and human trafficker,” Olsen said when I interviewed him on Zoom in December. “They try to remove credibility by posing me as the criminal.”

Olsen faces several ongoing investigations in Greece and has been unable to return to the country. The most recent alleges he “formed a criminal organization” to aid the “illegal entry” of migrants into Greece by sending the authorities their location and information so that they may be subject to asylum procedures.

In a December 28 letter to the Greek government, Mary Lawlor, the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders, expressed concern that criminal investigations of Olsen and Akhtar “may amount to the improper use of Greece’s legal framework to sanction their actions as human rights defenders.” Replying on February 24, Foreign Minister Nikos Dendias refrained from commenting on pending cases.

Since New Democracy came to power, camp conditions and asylum processing times have improved, but Greece’s migration policy has been subsumed under the banner of border security, penalizing asylum seekers and prioritizing “prevention over solidarity and human rights,” as Lawlor reported in March. The organizations and aid workers who promote and protect their rights “have been subjected to smear campaigns, a changing regulatory environment, threats and attacks and the misuse of criminal law against them to a shocking degree.” With dwindling funds and volunteers, these organizations will have to make difficult decisions as desperate migrants continue to land on European shores with no end in sight.

Top photo: The Souda open reception facility in the moat of Chios castle in August 2017. The camp was closed in October 2017 and its inhabitants were moved to Vial camp