OINOUSSES, Greece — As I passed a bronze mermaid statue entering this island’s idyllic harbor on the ferry from Chios Town, I could hear the church bells of Agios Nikolaos tolling up on a hill in celebration of the saint’s feast day. Agios Nikolaos is the protector of sailors and fishermen, and many of his miracles involve rescuing men at sea and calming rough waves. He is an important and beloved figure for the seafaring Greeks, and especially the 950 residents of Oinousses, where he is the patron saint.

With its long maritime tradition and hillside of boxy, pastel-colored kapetanóspita or captains’ houses, Oinousses is known as the island of seafarers. “In Oinousses, every home looks out to sea,” a local told me. The island’s monuments, like the statue of the Oinoussian mother in the harbor waving goodbye to her children as they start a long journey, and the statue of the unburied sailor in Naftosini Square—the first in Greece dedicated to lost mariners—also gaze seaward.

When I arrived on the morning of December 6, celebrations were already underway. Captain Fotis Margaritis came to fetch me from the port in a shiny, mustard-colored car. He had dressed in a suit for the occasion, and as he navigated up narrow lanes to the church, retracting his side mirrors with the flick of a button, we passed ferry passengers and young people headed in the same direction. Margaritis explained that the procession from the church would soon begin.

After changing into a button-down shirt, I joined the locals in the cathedral courtyard. Everyone had come out for the festivities: families in their Sunday finest, sailors in navy-blue uniforms and white hats, soldiers in camouflage, future captains from the Merchant Shipping Academy in black-and-white uniforms, white-gloved flag bearers and the descendants of Asia Minor refugees in traditional costumes. As the crowd grew, so did the anticipation. Then, as bells rang, two ship captains exited the church carrying the garlanded icon of Agios Nikolaos, followed by two standard bearers and a quartet of soldiers bearing an ornate wooden canopy with a holy relic of the saint that had been transferred to the island from Sicily in 2001.

The procession circled the cathedral, passed out the gates and down through the settlement to the water, followed by most of the village. The priest and the mayor took turns reading hymns, and as I ran ahead to take photos of the approaching group, I heard commands issue up and down the line to keep us going in the right direction, at a steady pace. We stopped to bless each of the island’s schools, the Merchant Shipping Academy, the Coast Guard and the memorial of the unburied sailor, where the mayor threw a wreath into the water to honor those who had died at sea. The icon and holy relic were even taken aboard the ferry on which I’d arrived and a gray military ship docked in the harbor. Finally, returning to the cathedral, four captains held the canopy aloft so we could all pass under the relic as we filed back into the church.

What struck me as we marched through the settlement was the omnipresence of Oinousses’s big shipowning families. Everywhere I looked, I saw the names of the island’s benefactors inscribed on streets, buildings and monuments: Lemos, Pateras, Lyras, Lignos, Hadjipateras. These families have been involved in shipping since at least the 19th century. Together with families from Chios, particularly its northeastern villages of Kardamyla and Vrontados, they contributed much to the successful postwar development of Greek and global merchant shipping.

From 1945 until the 1973 oil crisis, maritime trade increased six-fold, largely due to the transport of petroleum. During this period, “Golden Greek” tanker tycoons like Aristotle Onassis and Stavros Niarchos rose to mythic heights, dominating headlines with their jet-set lifestyles. The long-time rivals both married daughters of the powerful Chian shipowner Stavros Livanos.

The Greek-owned fleet has grown continuously since the end of World War II, even as dynamic industries developed in Japan and China. As of 2022, Greece remains the top shipowning nation in the world with 5,514 ships, approximately 21 percent of the global fleet in terms of capacity, according to the Union of Greek Shipowners. Shipowners from Chios and Oinousses control over 40 percent of Greek shipping, roughly 10 percent of global capacity. Maritime transport accounts for almost 7 percent of Greece’s GDP, the union report says. But according to a Reuters investigation, if Greece measured the industry like other countries do, excluding billions that never actually enter the Greek economy, shipping’s contribution would drop to 1 percent.

Meanwhile, Greek shipowners have attracted their share of controversy and criticism, from charges of corruption, concerns about their preferential treatment and political influence with governments of both left and right, concentrated ownership of the country’s media, tax breaks during the financial crisis, and resistance to carbon emissions rules and sanctions on Russia. Indeed, Greek tankers legally transported Russian oil even after the outbreak of war in Ukraine, an activity the latest round of EU sanctions has prohibited if purchased above the oil price cap.

During my visit to Oinousses, I sought to understand how families from this tiny island came to have such an outsized impact on Greek and global shipping, how the industry shaped daily life and culture, and how life aboard Greek ships has changed in recent decades. I learned that despite its difficulties, young people from Chios and Oinousses are returning to the profession, with Chian shipowners continuing to lead the way, controlling about one-fifth of the global liquified natural gas (LNG) carrier fleet and entering the market for floating storage and regasification units (FSRU) at a time when European energy security is a top priority.

Forward-thinking investments

The Chios Maritime Museum, housed in a neoclassical mansion back in Chios Town, and the Oinousses Maritime Museum near Naftosini Square were helpful starting points for learning about the islands’ nautical history. Both contain a wealth of paintings by the Vrontados-born folk painter Aristides Glykas, artifacts and ship models that track the development of the islands’ mercantile fleets from 19th-century sailing ships and 20th-century steamers to modern-day bulk carriers, gas tankers and container ships.

Due to Chios’s key position at the crossroads of ancient trade routes between the Mediterranean, Asia Minor and the Black Sea, shipping and trading have been profitable and complementary industries on the island since antiquity. Indeed, the Genoese explorer Christopher Columbus famously visited the island around 1474, some say to gather information and improve his navigational skills, others for Chian sailors to crew his ships. After the massacre of Chios in 1822, islanders fled to Syros island and Piraeus, which they helped transform into dynamic trade and maritime centers.

The modern history of Oinousses begins in the 18th century, when shepherds from Kardamyla brought their flocks across the strait to graze on the island. Gradually, they settled there, maintaining ties with relatives in Kardamyla. Although they started as an agricultural society, by the early 19th century, they turned to the sea to make their living, since the small, rocky island could not support the growing population. Instead of staying within the confines of Oinousses, they decided to throw themselves into the unknown, Oinoussian shipowner and former mayor Evangelos Angelakos told me. “They realized that here was the big, fertile field: the sea!”

Oinoussians like Angelakos’s great-grandfather initially worked aboard Chian sailing ships, rising through the ranks to become owners themselves. They started building their own vessels in 1848. During the Crimean War, they transported supplies for the Turkish army, earning money to expand their fleet. Nearly all the island’s inhabitants went to sea and prospered. By the end of the 19th century, they owned 160 ships that traded throughout the Mediterranean and Black seas.

The transition from wooden sailing ships to steamships was an important inflection point for Chios and Oinousses. Chian shipowners initially mistrusted steam-powered vessels and didn’t begin buying them until 1889, when they already carried over half the world’s sea trade. In 1905, nine Oinoussian shipowners from the Hadjipateras, Pateras and Lemos families followed suit, banding together to purchase the SS Marietta Ralli, the island’s first steamer, for 13,300 pounds. During World War I, Oinousses owned 10 steamships and Chios, 40. In contrast, the village of Lagkada missed the opportunity to convert its fleet and disappeared as a shipowning force.

The Greek government requisitioned Chios and Oinousses’s fleets during the two world wars, when the islands suffered great losses in ships and human lives. During World War II, 91 of the islands’ steamers were destroyed by enemy action and 328 seamen lost. Their names and villages of origin are commemorated on a memorial outside the Chios Maritime Museum.

An important factor in the Allied victory were the merchant steamers known as Liberty ships, mass-produced by the United States to deliver essential supplies to England and Europe. At the end of the war, some 100 of these ships were sold to Greece at a fraction of their cost to replace the country’s decimated fleet.

Shipowners from Chios and Oinousses bought 41 of these ships and three of seven T2-type tankers. The Liberties set the stage for the postwar renaissance of Greek shipping. That’s why, when a Chian captain’s wife gave birth to a boy in the postwar years, the custom was for someone to cry, “She’s made a Liberty!”—another son to add to the island’s maritime fortunes.

After learning so much about these “blessed” ships and seeing models and paintings of them on Chios and Oinousses, I was delighted to discover one of the three surviving Liberties docked in Piraeus right next to the gate where my ferry from Chios disembarked. The US government donated the SS Hellas Liberty to Greece to serve as a floating maritime museum, and she was towed into the port in January 2009. As I climbed the gangplank and explored the Liberty’s deck, cabins and bridge, I imagined leading her back out to the open sea.

Life at sea

During my visit to Oinousses and in my final months on Chios, I met a number of captains and seamen who described to me what it was like to serve on a Liberty ship and how that life changed as technologies improved, fleets grew and markets have become ever-more global.

Several themes emerged from those conversations. First was the hyper-local nature of the industry in its early days. Shipping was a family business, and owners and their male family members routinely served aboard their own ships. Much like the nobility that ruled Chios in the Genoese period, shipowning families often intermarried to concentrate wealth and resources. They crewed their ships with experienced seamen whom they knew and trusted from their home villages, reinforcing strong bonds among the crew, and good management.

“The crew loved the ship, and they were careful to economize,” said retired captain Antonis Glykas of Vrontados, who worked aboard the Liberty ships. He once saw Australian sailors wrap the remains of their breakfast—marmalade, butter, eggs—in a tablecloth and throw it overboard. “‘We’ll buy more in Athens,’ one of them explained. But we Greeks didn’t do that. If five packets of butter remained on the table, we’d keep them to use another day.”

Developing technologies have slowly changed ship culture. Captain Glykas told me that 38 to 40 seamen, all Greeks, worked on each Liberty ship when nothing was automated and everything had to be done by hand. Today’s much larger bulk carriers and container ships sail with crews half the size. As automation increases, crews continue to shrink.

Journeys were also much longer in the past. Crews were usually away from home two to three years, whereas now contracts are more strictly regulated and crews leave for six to 12 months—“a game,” Captain Fotis Margaritis said laughing.

Communication with loved ones was also more difficult before the internet. Stergios Ziglakis, who worked for 20 years as a cook and chief steward, remembers writing his wife letters and having to wait three months for a response. When one telephone came to the village, he had to call to ask someone to summon his wife, then call back later to speak with her.

“We had no privacy,” he said. “Everyone waiting for the phone in the village and everyone on the ship heard everything.” During the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s, when a reporter mistakenly wrote that Ziglakis’s ship had been bombed instead of the vessel next to his, the news struck his wife down with grief.

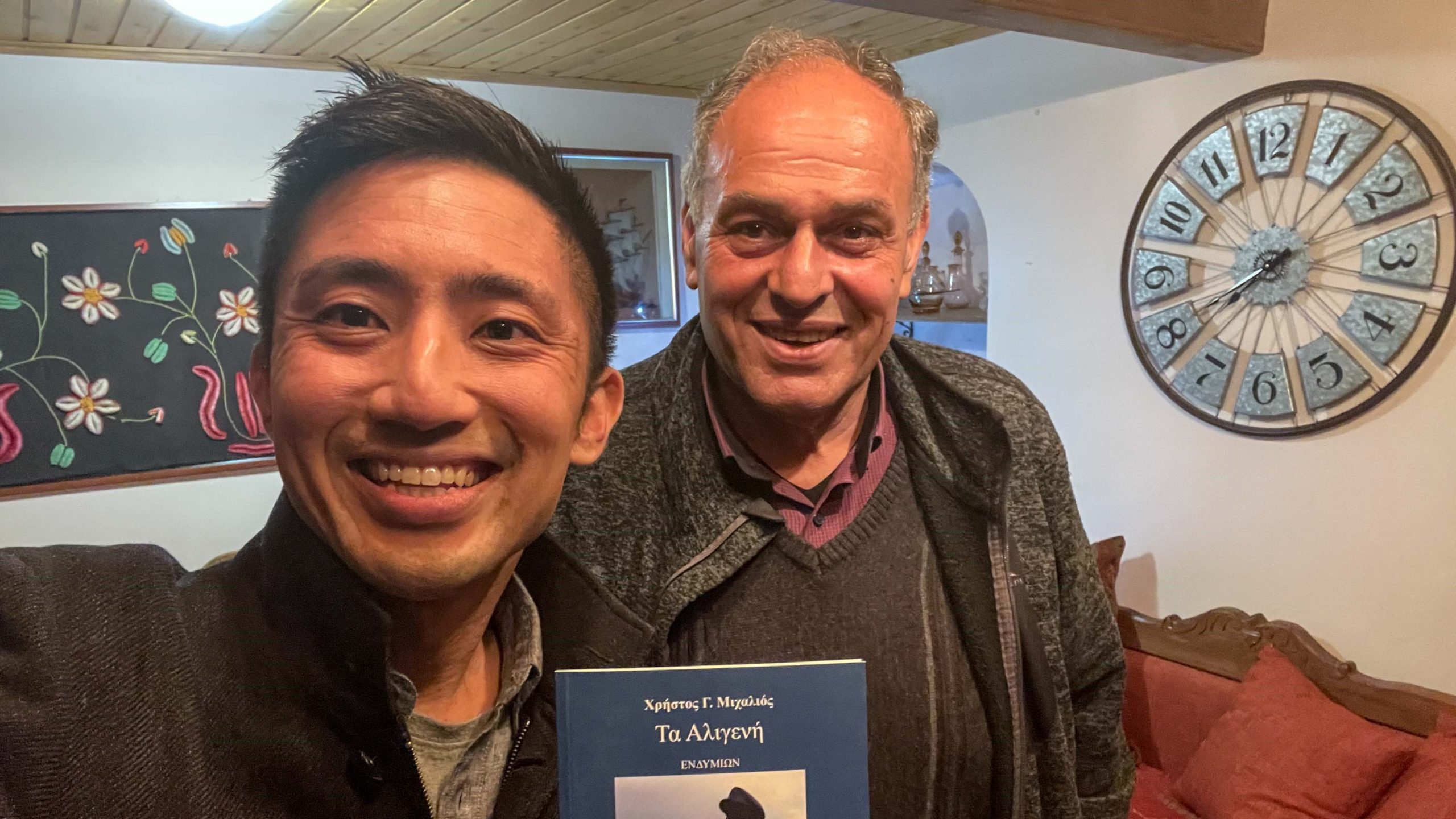

As a result of the conditions, seamen in earlier days formed indelible bonds with their shipmates. “They were all Chians, people from your village, and you were known to each other,” said retired captain and poet Christos Michalios from Kardamyla. “We used to gather in the smoking room to tease each other and tell stories to pass the time. Whatever tiredness or bitterness you had, it was a kind of psychotherapy. You’d say your problems, I’d say mine. We were all brothers, and we’d relieve each other of our burdens.”

Nowadays, crews are much more diverse, which hinders the feeling of camaraderie. “I’ve been on ships where I was the only Greek,” he said. “All the rest are from the Philippines or Maldives or different places. The love has been lost, the emotional communication. Now everyone sits in his room, opens his computer and talks with his family.”

The seamen I spoke with had traveled the world over. Ziglakis showed me a 1959 photo of himself taken astride a rowdy camel at the Great Pyramid of Giza and another in a tranquil Japanese garden. In his wife’s touristic shop on the Oinousses waterfront, Captain Margaritis scrolled through hundreds of photos and videos taken from the bridge of his bulk carrier as it sailed through the Bosporus Strait, the Suez and Panama Canals, as it loaded or unload cargos of coal or iron ore in Brazil and Sri Lanka, and as it traveled the open sea when monstrous waves pounded the deck. Interspersed were selfies he and his wife had sent each other.

Before ports were modernized, seamen could dock for 20 days while waiting to load or unload. That gave them time to leave the ship and explore the countries they visited. While many of his shipmates went out at night to bars or find girls, Captain Michalios preferred to leave the ship during the day to see the sights, talk with people and learn their way of life. “I count myself lucky,” he said. “In the last 10 years, you arrive in a port at 8 a.m. and leave at 10 p.m. latest. We went to Brazil to load, and 12 to 13 hours later, we left. Now you’re always on the ship.”

The frequent absence of seamen from their homes created a unique family situation back in Chios and Oinousses’s seafaring communities. Giannis Glykas, who runs the Chios Maritime Museum and whose father was a captain from Vrontados, recalls his father always keeping a packed suitcase by the front door so he’d be ready whenever the shipping company called.

“I don’t remember my father much until I was 15 or 16 years old,” he said. “It didn’t seem strange to me because for everyone I knew, it was the same,” In that environment, the kapetánissa—which originally meant “captain’s wife” but can now also mean “female captain”—held a critical role. “She was both mother and father, the protector of the family, the central pillar of the household,” said Captain Michalios. “She controlled the finances, and she had to look after everything, command everything, support everything, including her husband.”

Sailors’ homecoming brought joy to the whole neighborhood. Often they returned with suitcases filled with gifts, crazy with happiness at seeing their families again. Ziglakis once brought home a pair of canaries from Japan; another time, he brought 10 kilos of kashkaval cheese from Constanta, Romania. The months at home were a time to rest, celebrate, eat and drink.

As they prepared to leave once more, seamen often grew despondent. “Once my son didn’t want me to leave for anything,” Captain Michalios said. “He went to his room, brought me his wallet and told me, ‘I have money! Look! Don’t go.’” Michalios said he cried for two months. Despite the long voyages and the deprivations he experienced, he told me, he had the comfort of knowing his family lacked for nothing because he had a better salary than those who lived on land.

The next generation of shipping

Young people are returning to the sea, thanks to Greece’s decade-long financial crisis. The day after the celebration of Agios Nikolaos, I visited the Merchant Shipping Academy of Oinousses, one of the oldest of Greece’s 10 academies, which has trained sea captains since 1965.

An air of tradition pervades the imposing white building. Inside, the walls are painted in tones of white and blue, like the Greek flag. Inscribed above the double staircase is the dictum, “Acquire virtue before putting yourself at the wheel.” A shrine to Agios Nikolaos stands at the base of the staircase, and ship models and navigational equipment decorate the hallways.

The school is relatively small, accepting 40 students per year through the Panhellenic exams, a national competition that determines entry to Greece’s institutions of higher education. Lieutenant Commander Dimitrios Kloumasis, who directs the school, told me that incoming students’ performance on the exams is “very high,” and all list the academy as their first choice. “The last two years, our top student collected 19,400 of a possible 20,000 points,” he said. “The students who choose the merchant shipping academies, and especially ours, are completely decided. They know they want to become captains.”

The 160 students enrolled in the four-year program spend six semesters taking classes and two semesters on educational trips at sea. Around 75 percent are men, and most come from Chios and Oinousses. Upon graduation, they attain the rank of third captain. During the fall semester, the school suffered a lack of teachers, forcing students to miss educational hours. After marching in the November 11 parade to celebrate Chios’s Liberation Day, students protested in the main square, unfurling a banner that read, “We demand what we’re entitled to!” When I visited in December, Kloumasis said a solution had been found, with the Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Insular Policy agreeing to increase the teachers’ hourly wages.

The profession also faces challenges from within. Due to the long periods away from home, the loneliness of life at sea and growing extremity of waves and weather as climate changes, many captains don’t want their children to follow in their footsteps. When Captain Margaritis’s son was choosing a profession, he tried to discourage him from becoming a seaman.

“I tried to give him other options, but he wasn’t happy,” Margaritis said. “So we discussed it, and I told him, ‘I hope everything goes well, but it’s your decision. I don’t want you to say at some point that I took you to sea.’”

He recounted once meeting his son’s ship with his wife as it passed Oinousses. They had loaded a boat with care packages to hand over on the open water, where he was waiting in uniform on a lowered gangplank. “We had time only to touch his hand and say goodbye,” Margaritis said sighing, flipping through photos of the family’s momentary reunion.

Shipowners from Chios and Oinousses have traditionally invested in bulk carriers, transporting grains, ore, coal, lumber and other dry cargo. Like the merchants of Kampos before them, their businesses developed on an international scale, expanding beyond Europe and the Mediterranean in the interwar years. After World War II, they built ever-larger vessels, first in Japan, then South Korea and China. In recent years, many have gone on to diversify their fleets and invest in newbuilt ships. The total capacity of the Greek-owned fleet has grown 45.8 percent since 2014.

For CEO of Navigator Shipping Consultants Danae Bezantakou, who organized a forum for shipping executives and decision makers on Chios and Oinousses last September, Greeks’ ability to improvise, change course and adapt to the unpredictable demands of the sea serves as a competitive advantage. Today, as Europe’s energy security becomes a paramount concern and countries race to construct liquified natural gas, or LNG, terminals, Greeks own 22.35 percent of the global LNG carrier fleet. Much of that capacity is concentrated in the hands of Chian or Chios-linked companies like the Angelicoussis Group’s Maran Gas Maritime, the Livanos family’s GasLog (which is involved in the Alexandroupoli FSRU project), the Prokopiou Group’s Dynagas, and Tsakos Energy Navigation.

Most of the companies have invested in LNG carriers since the early 2000s. Kloumasis told me that students often want educational trips aboard these ships since they are the most lucrative. The Angelicoussis and Prokopiou groups have also entered the FSRU market, and in 2021, Prokopiou acquired the strategically significant Skaramangas shipyards near Piraeus.

The legacy of Greek shipping on island life

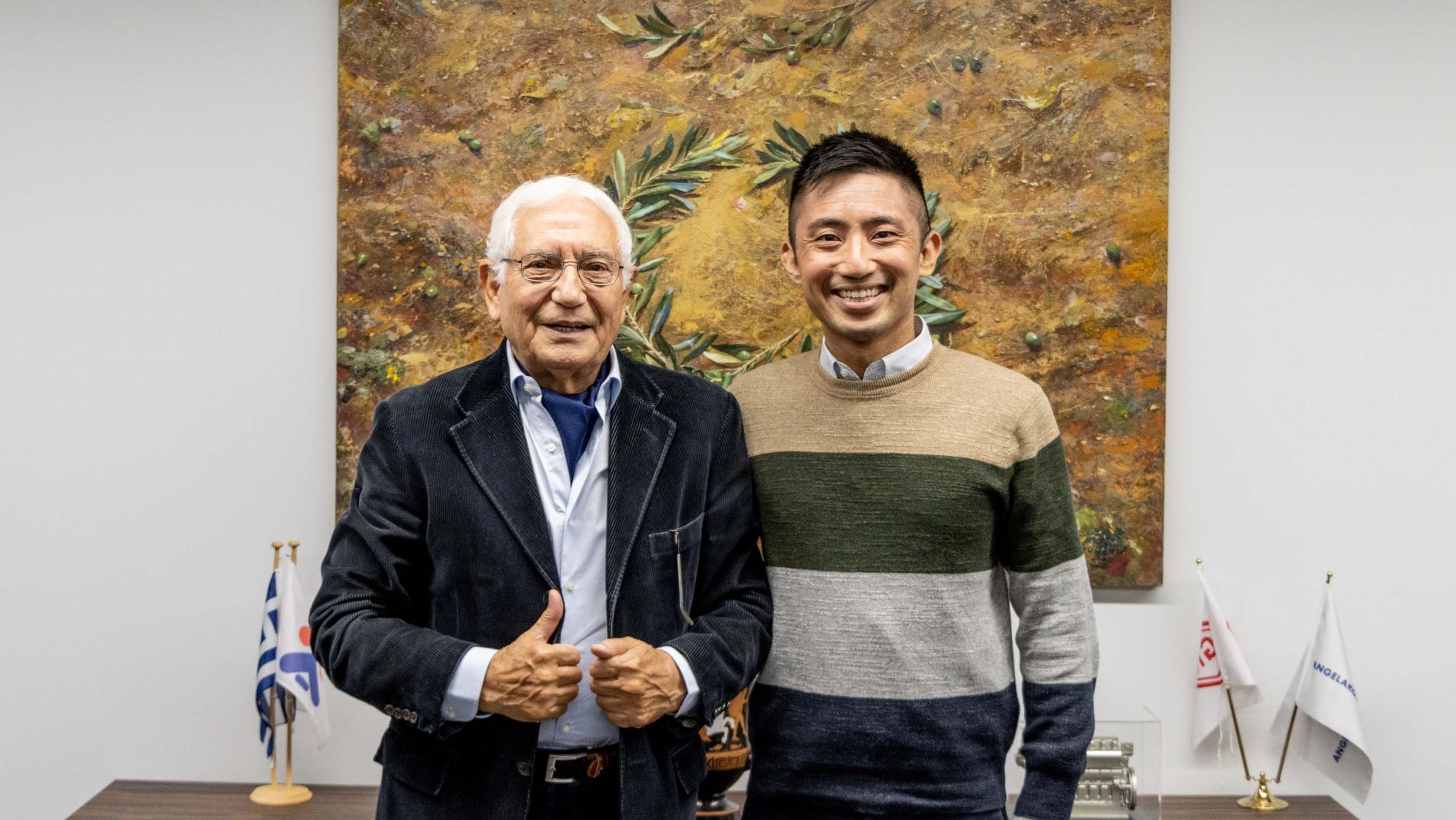

I met Evangelos Angelakos, a shipowner and former mayor of Oinousses, outside the cathedral of Agios Nikolaos after our procession through the village. A dapper man with white hair and a white ascot, he beckoned me over and, with a twist of his hand, asked what I was doing there.

Many Greek mariners work with Filipino crews, so I think my background and ability to speak Greek piqued his curiosity. Angelakos has a fondness for history, and as we walked down the hill from the church to a reception hosted by the municipality, he told me the story of his uncle, Zannis Evangelos Lemos, who served as chief officer aboard the SS Diamantis, the first Greek merchant ship to be torpedoed by a German submarine in World War II. Incredibly, the captain of the German U-boat took the crew members of the Diamantis aboard and landed them in Ventry, Ireland, a heroic action that put him and his crew in considerable danger.

A few days later, at Angelakos’s office in Palaio Faliro, near Piraeus, I had the chance to ask him more about his career as a shipowner. Angelakos is related to the Pateras and Lemos families, and he continued in the family tradition by starting a bulk carrier business in London in 1970. He told me about his entry into the car-carrying market, a “calculated risk” that involved buying dual-cargo ships to transport cars in addition to the usual dry cargo.

The risk paid off. At one point, he owned 10 such ships and an American broker called him “the car-carrying king.” On the whole, though, he played it safe, always able to rely on transporting grain or coal. “Never did I play roulette,” he said. “When I did my projections, I was always calculating the worst risks, putting on paper the worst income, the maximum expenses. Then I’d ask myself, ‘Do I make it?’ Luck does exist, but you can’t depend on luck.”

Angelakos criticized the current overregulation of the industry, a sentiment echoed by Captain Margaritis, who told me, “We have so much paperwork now. The captain used to be on the bridge. Now he’s a glorified secretary, sitting in front of a computer in his office. For every job you do, you have to confirm it was done safely. Even if you cut a piece of bread, you have to describe how you cut it.”

Such bureaucracy raises costs for the consumer, according to Angelakos. “You can’t run a business with losses,” he said, voice rising. “All right, you want me to employ one secretary there and another secretary there to do the work. I have to cover the costs, so I have to ask more for freight. So you, the consumer, be it in China, in America, in Germany, Greece, in the Philippines, you pay more for your bread! So yes to regulations, yes to green initiatives. But don’t overdo it, because at the end of the day, the people pay for it.”

As Chian shipping companies have grown into global entities fueled by international capital, some islanders feel they’ve abandoned their roots. “Over the last 20 years, the companies have become faceless,” said Captain Michalios. “Before, I knew them all. I went to the cafe and saw [shipowners] Ioannis Livanos, Carras, Xylas, and we’d exchange pleasantries. Their grandchildren and great-grandchildren who run the companies now haven’t grown up in Greece. They may be Greeks by ancestry, but lots of them don’t even know where Chios is.”

Though fewer shipowning families return to Chios and Oinousses for the summer, several have become the islands’ benefactors, as I’ve seen during my stay. The John. D. Pateras Foundation constructed and maintains several churches, hospitals and other public facilities on the island and offers scholarships to Chios students. Captain Panagiotis Tsakos founded the Maria Tsakos Public Benefit Foundation to promote maritime research, offer grants and scholarships and host cultural events in memory of his daughter. Two years later, he founded Maria’s Home, a boarding house in Kardamyla for underprivileged students. Similarly, the Prokopiou family has restored estates in the Kampos of Chios and donated to the Holy Metropolis and the volunteer firefighting force Omikron.

Shipping families also fund the operation of the islands’ maritime museums and maintain offices in Chios to recruit crews. The John S. Fafalios Foundation supports the Chios Music Festival and Keos Magazine, an annual publication inspired by the island’s stories and people. Stamos Fafalios is a patron of the contemporary art organization DEO Projects, which commissioned the Marseille-based artist Dominique White to spend two months researching maritime histories on Chios and work toward her first Greek exhibition. DEO Projects founder and director Akis Kokkinos told me he wanted last summer’s program to “create a more polyphonic, inclusive approach to the shipping industry and bring to light stories that hadn’t been told so far.”

As mayor of Oinousses for 16 years, Angelakos has continued the shipowners’ tradition of giving back to his community. He helped build up the island’s infrastructure with a new desalination plant, water and sewage system, peripheral roads and an expanded port to accommodate large vessels. He says he tried to instill a seafarer’s ethic in his compatriots, not by “caressing their ears,” as Greeks say, but with tough love. In the midst of Greece’s financial crisis, he sought to promote the traits he felt had made Oinousses great: entrepreneurship, self-reliance, forethought and broadened horizons.

“The people who built Oinousses worked very hard,” he said. “They were not waiting for the government or someone else to save them. They risked their lives, and about 300 seamen lost them, as you saw in Naftosini Square. That’s the price of success for a small place.”

Back on Chios, I visited the statue of the unknown sailor in Vrontados one gray, windy morning. The shipping villages all had monuments honoring their seamen, and now I saw them with new understanding and respect. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the dream of Greek shipping was akin to the American dream: a path to a better future through ingenuity and hard work. The islanders built this industry with their labor and sacrifice, working on dangerous seas, far from home.

I thought of the young cadets I met at the Merchant Shipping Academy, rediscovering the source of Oinousses’s wealth. Where would their careers lead them? Would Margaritis’s son thrive as a captain, or would he come to regret not taking his father’s advice? The unknown sailor stood apart on his rock, separated from me by waves that foamed over shallow rocks. Burrowing into my jacket, I stared out over the rippling sea.

Top photo: The bulk carrier Panamax Nostos, seen from the ferry to Oinousses