OLYMPOI, Greece — On a sunny afternoon toward the end of September, my neighbor Maria Tsetseri and I jogged through the narrow, winding streets of our medieval village with a burning torch as part of an island-wide relay race to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the Chios massacre. In 1822, a year into Greece’s war of independence, Sultan Mahmud II sent a fleet of 46 Ottoman ships and 7,000 armed troops to crush a revolt on the island and punish its inhabitants. From April to August, they slaughtered some 42,000 islanders, over a third of the population, and captured another 52,000 women and children, whom they sold into slavery.

The violence marked a watershed in Chian history. Never again was the island so prosperous, and many survivors fled westward, never to return. Shock at the atrocities reverberated across Europe, generating support for the Greek cause. Artists like the French painter Eugene Delacroix, who had never visited Chios, immortalized the killings in his 1824 Massacre at Chios, which hangs in the Louvre. In the foreground of his painting, victims’ exposed bodies are stacked in two pyramids of pain. A wounded man lies naked on the ground, his dark eyes vacant, dead or near death. A woman tied to a soldier’s horse writhes against her bonds, and a child seeks comfort from its mother’s blued corpse.

Delacroix’s painting is steeped in Western constructs of Romanticism and Orientalism, depicting the East as barbarous and backward, of course, although according to the British historian Roderick Beaton, the war was a “descent into savagery” with both sides routinely resorting to “the most extreme violence imaginable.”

Copies of the painting are ubiquitous on the island. The image greets visitors at the entrance to the Byzantine Museum of Chios, housed in a former Ottoman mosque, and at the Massacre of Chios Museum at the Monastery of Agios Minas. In 2021, when Greece celebrated its bicentennial, Delacroix’s suffering figures were projected on buildings across the country. It is reprinted in Chios guidebooks and the brochure “Memories of Centuries Past,” a municipal campaign to commemorate both the 1822 massacre and the 1922 Asia Minor catastrophe and burning of Smyrna, a second tragic Greek anniversary I will discuss in my next dispatch.

As Olympoi’s participants in the relay, four other young people and I wore white jerseys with Delacroix’s painting printed on the back. We gathered along the road at the village entrance to welcome runners carrying the torch from the neighboring settlement of Pyrgi. The cultural association had set up a small table offering water, melomakárona cookies and soumáda, a sweet drink made from almond syrup. The president and vice president wore traditional costumes to mark the occasion. Over three days, the torch would pass through every village on the island, from the mountainous north to the dry, mastic-producing south.

As we ran along the route Maria and I had practiced twice that morning, I wondered, what other event could inspire such island-wide participation? In the face of escalating tensions with Turkey, a relay honoring victims of the massacre seems to have struck a communal chord.

At its nearest point, Chios sits only 3.5 nautical miles from Turkey’s western coast. Day or night, the opposite coast, with its wind turbines and blinking red lights, remains present on the horizon. The author Giannis Makridakis described in a blog post the special term Chians use for the land across the strait. “For those of us who grew up on the island, when we say or hear or read the word apénanti, [meaning ‘across, opposite,’] our mind automatically goes to the Turkish coast,” he wrote. “It’s more than a synonym. Apénanti means Turkey and [the town of] Cesme.”

Apénanti is a relational term, changing depending upon the speaker. It can mean “opposite” but also “opposing,” and it seems to capture how Chios’s neighbors are simultaneously close and just out of reach. For many Chians, the word has an additional resonance: It is the homeland lost 100 years ago when Turkey gained its independence in the Greco-Turkish War and expelled their ancestors from Asia Minor. Some, like tour guide Thomas Karamouslis, see the current borders as “artificial.” Gazing across the water, he told me, “these coasts have been held together much longer than they’ve been held apart.”

After nearly four centuries of Ottoman occupation, what Greeks call Tourkokratía or “Turkish rule,” relations between Greece and Turkey have been acrimonious and at times bloody. Although they are NATO allies, the two countries have long argued over maritime and airspace boundaries, hydrocarbon exploration rights and Turkey’s occupation of northern Cyprus.

Chios has often found itself in the center of these disputes. Tensions between the two countries flared again this past summer, when Turkish politicians depicted Chios and other Greek islands as Turkish territory. Ankara accused Greece of landing military vehicles on Chios and Lesvos in violation of the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, claiming Greek sovereignty over the islands is contingent on their demilitarized status.

Greece, for its part, insists its sovereignty over the islands is unconditional and maintains a right to self-defense since President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has intensified his rhetoric in the lead-up to Turkish elections, threatening Athens with missiles and repeatedly warning that Turkey can “come suddenly one night,” a call-back to its 1974 invasion of Cyprus. At the end of January, a pair of Turkish F-16 fighter jets flew over Chios and nearby Oinousses. Violations of Greek airspace have risen dramatically since 2021.

Greece’s foreign policy has long been affected by what Foreign Minister Nikos Dendias calls Turkey’s “Ottoman expansionism.” In 2021, Greece inked bilateral defense agreements with France and the United States partly as a bulwark against Anakara’s threats to its sovereignty. “The aggression we face from our neighbor does not allow the luxury of voting against this agreement,” Dendias said ahead of a parliamentary vote on the French pact. Some Greek and US analysts attribute Erdogan’s recent anti-Greek rhetoric to nationalist electioneering in the face of Greece’s growing transatlantic ties. Others, like commentator and former US naval officer Demetries Grimes, see it as a “clear and present danger” from a “rogue ally.”

But after the devastating February 6 earthquake that claimed over 50,000 lives in southern Turkey and Syria, political calculations are now up in the air, with “earthquake diplomacy” helping to normalize Greek-Turkish relations at least in the short term. Greece immediately dispatched a disaster response unit, and Foreign Minister Nikos Dendias visited the stricken areas with his Turkish counterpart Mevlut Cavusoglu. Meanwhile, Chios shipped eight pallets of basic necessities to victims, and various island organizations also collected aid.

Like the residents of Evros, Chians take seriously their role as akrítes, “frontier dwellers and guardians of the border.” The word, often used by officials who visit Chios, encapsulates islanders’ anxiety, defiance and pride over being on Greece’s front line. After Turkish media claimed in 2021 that Athens was conducting military exercises on the “occupied island” of Oinousses, locals unveiled a huge Greek flag. “May the akrítes sleep peacefully,” said General Konstantinos Floros, chief of the Hellenic National Defense General Staff on Chios last October.

Following the Chios Massacre Memorial Route, I decided to visit the island’s memorial sites to see how the island remembers the massacre and commemorates its victims. By seeking out these somber monuments and speaking with locals involved in the development of the new Massacre of Chios Museum at the Monastery of Agios Minas, I learned that the event is central to the history and identity of the island. The inherited trauma of 1822 lives on in local memory, adding to the discomfort Chians feel when faced with continued provocations from Ankara.

A pilgrimage to sites of the massacre

Chios’s ruling classes hesitated to join Greece’s struggle, knowing they had much to lose by aiding the rebels. The island enjoyed immense privileges due to its commercial prowess, including relative political autonomy, religious freedom and relaxed taxation. The pre-revolutionary years were a period of unrivaled growth and prosperity.

Chian merchants sold silk, wine, citrus fruits and other luxury items, and formed business communities across the empire, Europe and the Black Sea. They sent their children to study in Turkey and supplied Constantinople with the rare, aromatic mastic resin much desired by women in the sultan’s harem. The island’s proximity to Asia Minor meant that any uprising would face swift retribution, and it was not prepared for war. According to one account, there were hardly enough guns even for hunting partridge.

At the outbreak of the revolution in 1821, an Hydriot squadron arrived at Chios to urge residents to join the revolution. Chian participation would secure resources and an important naval base for the Greek cause. Island leaders managed to rebuff the request, but afterward, the Turks held Metropolitan Platon, his archdeacon and about 40 elders hostage in the prison of Chios castle.

The following year, Chian glory-seeker Antonios Bournias convinced Lykourgos Logothetis, the chief of neighboring island Samos, to lead a second ill-conceived attempt to liberate Chios. Samian insurgents roused locals from the countryside and attacked the castle and Muslim establishments. When news of the raid reached Constantinople, the sultan ordered Admiral Kara-Ali and his forces to lay waste to “ungrateful” Chios, killing all infants, women over 40 and men over 12 unless they converted to Islam. The hostages in the castle were hanged from trees in Vounaki Square, the central square of Chios town, where last September, runners lit the torch that would be carried around the island. Those trees still stand today, and after learning of the executions, it felt unsettling to see them decked in holiday lights.

At the edge of Vounaki Square stands the monument of the hanged, a marble obelisk engraved with a sphinx, the symbol of the city, and the names of the metropolitan, archdeacon and 56 island leaders who were executed within an hour and a half. They were Chios’s most influential citizens. I’d learned about many of those families—Argenti, Mavrocordato, Ralli, Schilizzi—from researching the neighborhood of Kampos, where country estates still bear their names. The memorial, erected at the expense of Alexandra Philip Argenti, a descendant of the Schilizzi and Ralli families who married Philip Argenti, commemorates the “noble Chians” who were “killed for their faith and their fatherland.” When I spoke with Kampos residents, several proudly referred me to the monument, evidence of their families’ long history on the island.

The massacre began on March 30, 1822, the Thursday of Holy Week, just days before Easter Sunday. Ottoman ships fired on the town, reducing it to rubble. Chians fled to the countryside, hiding in caves, basements and tombs while the weak and elderly were slaughtered in their homes. Richard Calvocoressi, the descendant of a prominent Kampos family, wrote in The New Statesman that the bloodbath was “essentially a holy war.” His three-times-great-grandfather Ioannis Kalvokoresis “had his fingers chopped off one by one for refusing to hand over gold to his captors and for resisting conversion to Islam.” Ioannis’s “90-year-old mother, her arms outstretched in the form of a cross, was walled up alive for refusing to renounce her faith.”

Brutality raged across the island. Troops brought severed heads and ears to the Ottoman governor, seeking rewards for their effectiveness. Escaping ravaged villages, 3,000 women and children sought refuge in the monastery of Agios Minas, not far from Kampos, while others went to Nea Moni, the 11th-century monastery now recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

The high walls of Agios Minas offered a measure of protection, but on Easter Sunday, Turkish forces surrounded the monastery, blasting its walls with cannons. After six hours, they breached the structure, killing all in their path. They set fire to the temple, slaughtering those barricaded within, and threw burning mattresses down into the cistern, where the last survivors hid. Nea Moni fared no better: the monastery was pillaged and hundreds of monks were murdered.

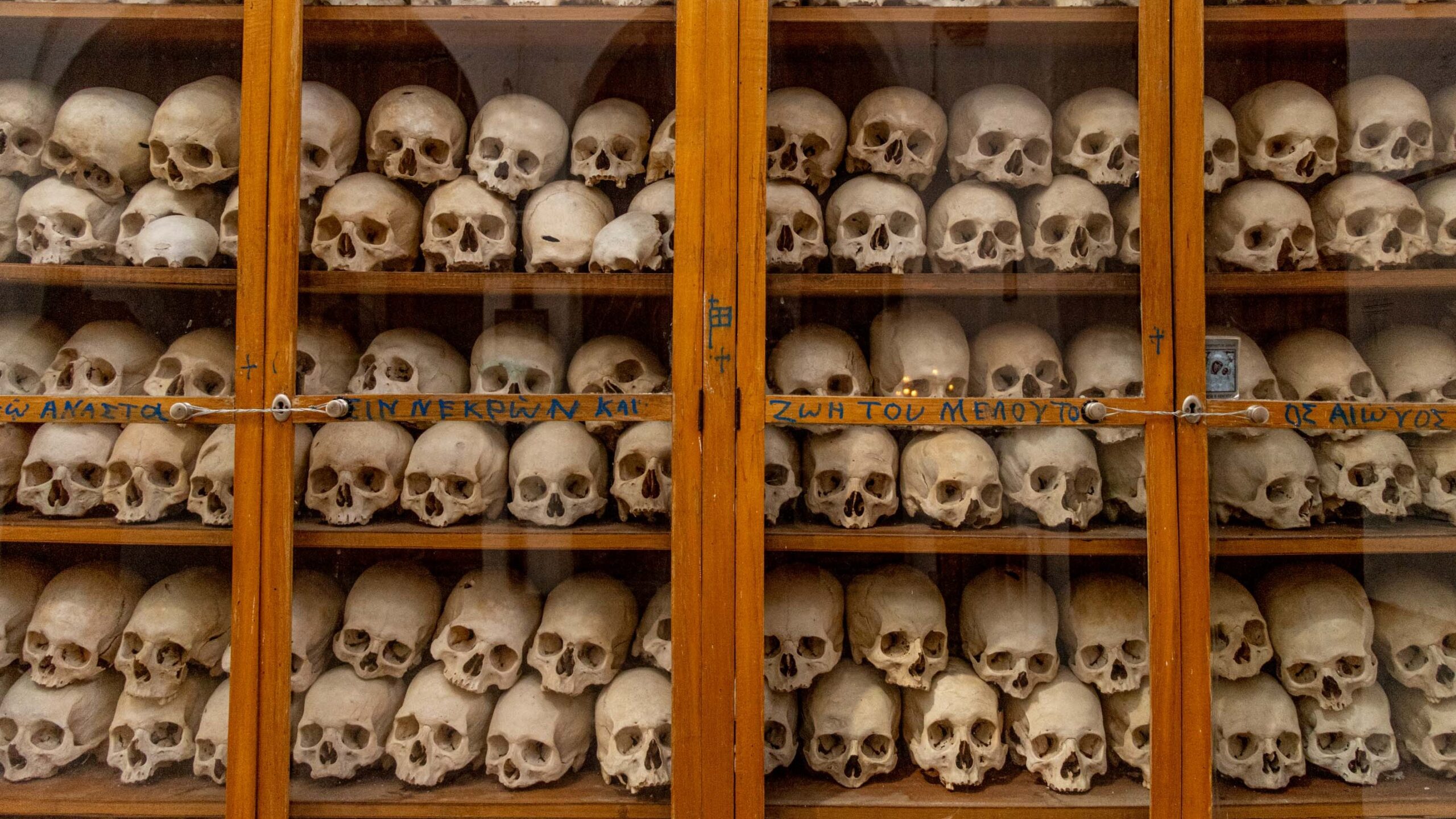

Today, both monasteries display victims’ bones neatly stacked in glass cabinets. It was a chilling sight, shelves of hollow-eyed skulls staring back at me through the glass. Each represented a life cut short, testifying to the horror of those days. It reminded me of memorial sites to other mass atrocities, like the Killing Fields in Cambodia, where human remains help visitors appreciate the scale of violence inflicted upon the civilian population. In the reconstructed temple of Agios Minas, one can also see brown and reddish discolorations on the original marble floor, which, as a framed sign informed me, is “from the burnt flesh and blood of the faithful.”

The monastery’s Massacre of Chios Museum opened in November 2021 as part of the Orthodox Church of Greece’s program to celebrate the Greek bicentennial. The brainchild of Metropolitan Markos of Chios, Psara and Oinousses, the project was funded by the Athanasios and Marina Martinos Foundation and realized by Manoliadi and Vournous Architects and a team of local collaborators. With its eye-catching, bilingual display boards, well-curated artifacts and atmospheric videos, the museum serves as a launching point for those wanting to learn about the massacre. By detailing the events of the slaughter at Agios Minas, it contextualizes the human remains and links the monastery to other memorial sites around the island.

According to former Mayor Manolis Vournous, half the architectural team responsible for the project, the museum aims to communicate in an effective and engaging way what happened during the massacre, thus filling an important gap in the island’s presentation of its history both for visitors and locals. “The bishop wanted to stress two things,” he told me. “First, the sacrifice of so many people, and second, the impact this sacrifice had in shifting international public opinion in favor of Greece’s struggle for independence.”

Vournous worked with Chios historian Athina Zacharou-Loutrari to condense her extensive research into “a well-structured narrative,” using “representative information” and primary sources so that people who wanted to spend 10 minutes in the museum could leave with two or three key points in mind.

The museum’s main artifact is a door from the monastery’s outer wall that was bombarded during the Turks’ siege. Previously located in the small chapel with the bones of the massacre victims, it is now the focal point of an entire room, where it lies at a 45-degree angle so visitors can lean over it and see the battery and bullet holes it absorbed before it fell. “The Turks exercised all their power on that very leaf,” Vournous told me. “And behind it were all the people inside the monastery and their hopes for salvation. When you study that door, you begin to understand the strength and magnitude of the assault.”

Another highlight are four historical videos produced for the museum by filmmaker and former Fulbright fellow Eirini Steirou. Each about five minutes in length, they chronicle the massacre across the island, its contribution to Greek independence, the siege of Agios Minas and the modern history of the monastery. For Steirou, the videos—especially the two dealing with the events of the massacre—presented a unique challenge. “You want to engage [visitors], you want to give them a cinematic experience, but you don’t want to trick them and make them feel like they’re going to be in the shoes of the people who suffered,” she told me. Reenactments were out of the question for her unless she could guarantee every last detail was accurate. “You want to show the trauma but without perpetuating hatred and intolerance between people,” she said. “So no way, we didn’t want to say the ‘good’ Greeks and the ‘bad’ Turks.”

While preparing for this project, Steirou was influenced by films about the Holocaust, especially Claude Lanzmann’s 9½-hour Holocaust documentary Shoah, which she called a “milestone.” The film didn’t use any archival footage, instead relying on witness testimonies interspersed with modern footage of Holocaust sites and extermination camps.

In a similar vein, Steirou layered narration and first-person accounts over evocative images of Chian landscapes and memorial sites. She adopted “the point of view of a contemporary observer” visiting Chios castle, Agios Minas, Nea Moni and other epicenters of the island’s history. She and her team shot at the abandoned village of Anavatos, where women threw themselves from the steep cliff to avoid being captured and disgraced, and at the lonely northwestern cape of Melanios, across from the island of Psara, where over 10,000 Christians desperately awaiting rescue were slaughtered, dyeing the sea red.

Steirou was also inspired by the Nobel Prize-winning poet Wisława Szymborska’s poem “Hatred,” which she excerpted at the end of the video chronicling the massacre: “Hatred is a master of contrast, / between explosions and dead quiet, / red blood and white snow. / Above all, it never tires.” The video’s poetic use of contrasting images, light and shadow insinuates much of the violence described in the narration without showing a single drop of blood. Instead, the viewer sees waves crashing against castle walls, smoke rising from the ruins of stone buildings, clouds racing over gnarled, barren trees. Like a refugee, the camera peeks out at the blue sky from deep inside a cave. A drone shot tracks over the vertiginous drop at Anavatos, mimicking the women who leapt to their deaths. Doom is implied by a closing door or snuffed out candles.

“I wanted viewers to have a feeling in their gut,” Steirou told me. “I wanted them to feel that human life is important. Hatred finds ways to feed itself, but above all, we are humans. These people suffered for a reason, but now, let’s respect human life and not tolerate more suffering.”

In retaliation for the massacre, the Greeks attacked the much larger Ottoman fleet with bourlóta or “fire ships.” These were old boats filled with explosives, straw and dry branches, soaked in tar and oil. On the moonless night of June 6, 1822, while the Turkish admiral celebrated victory and the end of Ramadan aboard his 84-cannon flagship, Psarian Konstantinos Kanaris and his crew stealthily fastened a fire ship to the enemy stern. The fire spread to the powder keg, killing the admiral and 2,000 Turks, as well as about 700 prisoners in the ship’s hold.

The blow to the Sultan’s fleet made it impossible to resupply the Peloponnese by sea and stifle the revolution. Kanaris’s brave defense of his community made him a war hero, inspiring philhellenes around the world. Artists like the Greek painter Nikiforos Lytras and French writer Victor Hugo commemorated his daring feat. He went on to become an admiral in the Greek navy and served five terms as prime minister. Today, statues honoring Kanaris can be found throughout Greece, in the public garden of Chios and in his birthplace of Psara.

Admiral Kara-Ali was buried in the Ottoman graveyard in Chios castle. Kanaris’s attack brought another wave of destruction to Chios, including mastic villages like Olympoi, which had until then been exempted from the massacre. By the end of the summer, the island was reduced to rubble and ash. From a population of 117,000 Christian inhabitants, only 1,800 remained.

“Human life in the 19th century had literally zero value,” Steirou said. “People were so expendable, we cannot even imagine today.” In addition, she said that by focusing on those killed, the official history often understates the plight of some 52,000 women and children who glutted the slave markets of Constantinople and Smyrna.

Three years later, in the summer of 1824, the island of Psara was also invaded and destroyed by Ottoman forces, which sought to cripple the Greek fleet and avenge Kanaris’s exploit. Dionysios Solomos, author of the Greek national anthem, commemorated the massacre in a moving poem still taught to Greek school children:

On the all-black ridge of Psara

Glory walks by herself taking in

the bright young men on the war field

the crown of her hair wound

from the last few grasses left

on the desolate earth[1]

The legacy of the massacre

The Chios massacre is widely acknowledged as a defining rupture in the island’s history. It wiped out entire families, entire industries, and much of the island’s wealth and cultural heritage, contributing to the spread of Chians across the world. For many, an air of tragedy pervades the island to this day. “There are no Chians who haven’t heard of the massacre or don’t have in the corner of their mind what happened then to Chios,” Athina Zacharou-Loutrari told me.

Virtually all the material I saw framed the massacre as a great sacrifice for the creation of a free Greek state. “The massacre was a key event in the revolution, the only one in which Chians find themselves,” Vournous said. “It’s how we connect ourselves with Greece’s liberation.”

Because Chios was a known island with a trading network spanning Europe and the Black Sea, the European press reported extensively on the massacre, and influential Chians living abroad mobilized their contacts and organized fundraisers to buy back captive women and children. The atrocities on Chios and the David-and-Goliath story of Kanaris sinking the Turkish flagship reinvigorated the philhellene movement, inspiring notable writers, poets, painters and sculptors to express solidarity with the likely birthplace of Homer.

In fact, cultural affinity decisively impacted Europe’s identification with the Chian victims. European elites studied classical art and philosophy and viewed the ancient Greeks as their cultural forebearers. The massacre of so many Christians provoked feverish rhetoric across Europe reminiscent of the Crusades. The scholar Yianni Cartledge describes the massacre as a pivotal event that “humanized” Greeks in the eyes of the West. As Europe saw Greece as more Christian, they simultaneously portrayed the Ottomans more as the Muslim “other.” Ultimately, the martyrdom of Chios tilted the great powers in favor of Greece’s revolutionary struggle.

The closing celebration of the three-day torch relay was held at sunset in Vounaki Square. I stood by the circular fountain, wearing the white jersey with Delacroix’s painting I’d earned running through Olympoi. A crowd had gathered around the stage, and participants held lit torches. I thought about everyone who had participated in the relay over the past three days. Not just the 150 registered runners and cyclists but also the hundreds who had gathered to greet the athletes at each stop along the way.

“You should ask yourself, why was the island so receptive to this relay?” Vournous said. “It’s not just because of the magnitude of the original event.” Many peoples have inflicted pain on Chios in the past. Persians subjected it in antiquity, Algerian pirates assaulted it, the Genoese heavily exploited the island for centuries, and Germans occupied it during World War II. But for him, those tragedies “belong to history.”

But throughout the 20th century, Chios’s closest neighbor has repeatedly shown animosity toward Greece with the “genocide” of 1922, the expulsion of the Greek community from Constantinople in the 1950s, and the 1974 invasion of Cyprus. Those events have compounded the islanders’ sense that successive Turkish governments, like their Ottoman ancestors, have wanted to do Greeks real harm. “Every few decades, Turkey comes back and says, ‘I am your enemy. I have you in my sights,’” Vournous told me.

Greece declared independence from the Turks two centuries ago, and although they share many cultural similarities, it has largely defined itself in contrast to its neighbor. The perception of a communal threat from apénanti has contributed to the formation of a Greek national identity steadfastly aligned with the West and—since the fall of the military dictatorship in 1974—committed to democracy and international law.

As Erdogan embraces neo-Ottoman policies, disputing Greek sovereignty over the eastern Aegean islands, Chian akrítes once more find themselves in Ankara’s crosshairs. By collectively reviewing lessons from the past, they seek to better understand the present and prepare for the future. “We were massacred,” Vournous said. “‘We’—and I include myself in that. Because this tension still exists, we still identify—maybe in the back of our heads, unintentionally but automatically— with our ancestors from 200 years ago.”

Endnotes

[1] Translation from Greek by Eleni Sikelianos and Karen Van Dyck

Top photo: The Glory of Psara, also funded by the Martinos Foundation, stands at the foot of Mavri Rahi, the “Black Ridge” where Psarians held their last stand. Nikos Georgiou’s statue, completed in 2021, is inspired by Solomos’s poem and a painting by Nikolaos Gyzis