TAIPEI — Under a moonlit canopy of bare tree branches, two men in black leather jackets lean against a brick wall. Their exchange is wordless, with only slow movements forward: A lingering gaze, twice over the right shoulder. A hand, stretching over the tense distance between them. One’s fingertips meet the other’s thigh, gradually wrapping around as a claim over the other’s body for the night. But just as a breeze rustles the canopy above, the other clicks his tongue almost inaudibly. He pushes himself off the wall and away from the grips of this dark park corner, emerging into the streetlamp-lit expanse of Taipei’s streets.

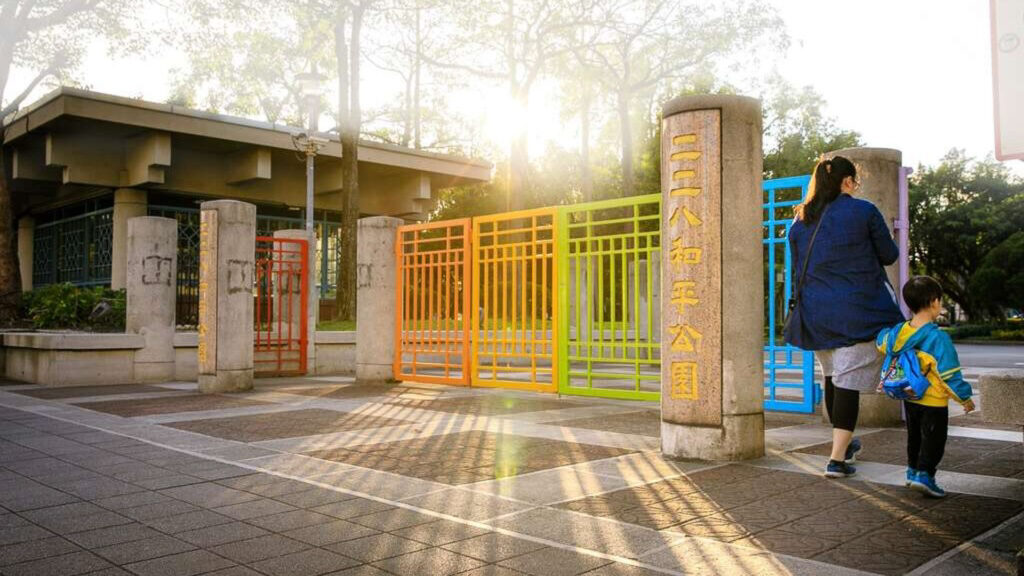

I think of this scene, from the 1995 Taiwanese film “Where is the Love?” by the lesbian director Chen Jo-fei, whenever I walk through 228 Peace Park, formerly known as New Park, in central Taipei. In the latter half of the 20th century, it was one of the city’s most well-known gay cruising districts, where men picked up other men through a social code of gazes and grazes.

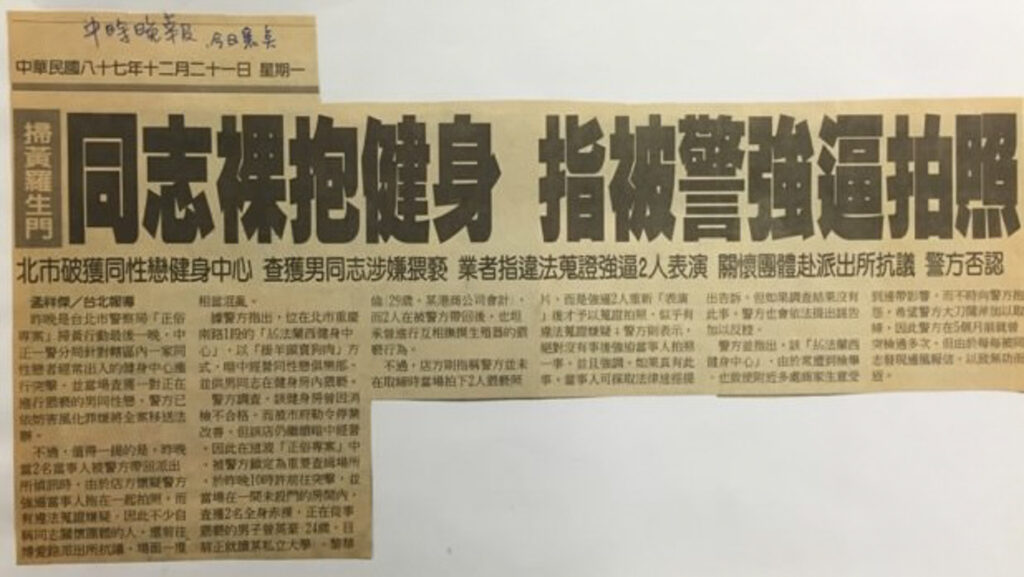

The news media painted the park as a den of iniquity. As early as 1959, United Daily News published exposés of a “homosexual culture of prostitution” in New Park, calling for more streetlamps and police crackdowns in the name of public decency and morality. Through the 1990s, the literary scholar Ting Chih-chi writes, these gay men, whether prostitutes or not, were often singled out by “an unnamable Nationalist operation of shame, backed by the Police Offense Law and by a series of insulting descriptions… in journalistic discourse” that cemented a lasting association between gay sex and AIDS.

Despite the risk of often violent police harassment, along the silent banks of its lily pond and patchwork of shady outgrowths, New Park was one of the few public spaces where gay men could find kinship, sexual or social, and realize they were not alone in their identity. In the classic Taiwanese novel Crystal Boys, set in 1980s Taipei, a group of young gay men form a chosen family there after their biological families disown them. In his 2005 ethnographic monograph titled Going to the Company to Work: New Park as a Gay Male Erotic Space, the LGBTQ+ activist Lai Zheng-zhe recounts the experiences of men “excited to the point of fainting” when lurking around New Park for the first time. He describes the park’s geographical order, with certain age groups or sexual preferences gathering around different landmarks. Here, hidden from society’s judgmental gaze, gay men held one another’s desires and bodies with care and hunger that could not be fulfilled elsewhere.

Less than a mere 30 years ago, darkness felt like a necessary precondition for members of Taipei’s gay community to be themselves.

But in today’s Taipei, not only is a rainbow painted over the eastern gate of 228 Peace Park—now redeveloped and mostly well-lit—but just a 15-minute walk away, pink fairy lights illuminate a rainbow flag hanging over a two-story complex of open-air bars and gay lifestyle shops. Most weekends at night, diva pop and electronic remixes overlap and scaffold the tipsy shouts of gay men across an open-air plaza.

In 2006, over a decade before same-sex marriage was legalized in Taiwan in 2019, gay men (and other members of the LGBTQ+ community, albeit with less frequency) were already beginning to gather in the Ximen Red House Plaza—known today as the epicenter of gay life in western Taipei and an (albeit imperfect) symbol of inclusion for LGBTQ+ people into the cityscape.

Curious about how gay men emerged from the dark park corners of the 20th century into the bright reverie of the Ximen Red House Plaza, equipped with a public space some can call their own, I wanted to find out where and how much further the LGBTQ+ movement has since gone.

In closets and basements: going out before the Red House

Before the Red House, when the lights turned on, the gays dispersed.

But ask a gay man about nightlife during this era, and a mischievous glint will likely shine from his eyes. Besides park corners, I’ve heard stories of train station restroom stalls with flickering bulbs and saunas in gym complexes—cruising hotspots propagated by word of mouth and, later, online bulletin boards. Even picking up a men’s magazine in the stacks of the 24-hour Eslite Dunnan bookstore was a signal to other lurkers, all reading the room for late-night company. Some would even clip photos or tear pages from unpurchased magazines.

The urban planning scholar Wu Chia-yuan described Taipei’s earliest gay bars and clubs—TAKE in the ’70s, Ming Jun in the ’80s, FUNKY and teXound of the ’90s—as “oases in an urban desert.” Here, past nondescript iron gates and down steep staircases, into the tobacco haze of neon lights in basement dancefloors, gay men could see and be seen by one another, temporarily freed from the self-loathing and discrimination they faced aboveground.

“Each performance was an indulgence in our wildest dreams and desires,” a long-time bar owner, DJ nightlife event organizer named Alvin Chang told me, his face brightening as he recalled his early career in the mid-1990s. Chang was inspired by his travels to the United Kingdom to organize “Gay Nights” at a club near his home called The Source, which did not explicitly cater to a gay clientele at first. But one night, Chang covered The Source’s dancefloor with paper-mâché rainbow flags he taped together himself, unable to purchase a readymade one anywhere in Taiwan. Thanks to just word-of-mouth and postcard-sized black-and-white street flyers he distributed outside FUNKY, Chang’s first event was an explosive success.

These events—which later transitioned to FRESH, a gay bar he opened with two of his friends in 2001—became the stage for a generation of female impersonators and drag performers: a bartender renowned for his impersonations of the actress Tsai Chin; a Taiwanese pop and folk diva popular in the 1970s through 1990s; a performing arts student who performed Beijing Opera in full theatrical makeup. Many appeared free, because of friendship and the desire to stage what they could not elsewhere.

The duality of their lives was never lost on anyone in the scene. “One time, a customer’s mother barged into FRESH to drag him home and he immediately jumped behind the bar to hide,” Chang told me. “And just like that, we were always hiding.” With a persistent stigma placed on LGBTQ+ identities in the 1990s, this story is relatively tame.

Even as the LGBTQ+ movement gained momentum, newspapers published voyeuristic articles that gawked at objectified gays and lesbians in these bars. Between 1997 and 2001, a police raid of a well-known gay cruising hotspot or bar made front-page news at least once a year: the 1997 Changde Street Incident, the 1998 AG Club Incident, the 1999 Gongguan Corners Bar Incident, the 2000 Beitou 24 Hall Sauna Incident, the 2001 FUNKY Bar Incident.

With each incident—a word that sterilizes the ways gay men were insulted, photographed and shoved into police cars without rights or recourse—the state continued to encroach on the community’s scarce sense of safety. It’s no wonder that even as the Taipei city government began funding public outdoor events like the first Taipei Pride in 2003, some LGBTQ+ people “criticized the organizers for bringing unwarranted attention,” Hsiao Chiang-ming, the owner of the Red House Plaza bar Mudan, said. “Some of us just wanted to be left alone in our basements, where we were relatively free of trouble.”

But in 2006, quietly, the gay community moved above ground.

Video footage of Paradise Party, a monthly party series focused on drag and ballroom performances organized by DJ Victor Cheng in the 1990s. Chang, who considered DJ Victor a mentor, was inspired by Paradise Party to bring drag into his own venues

From ‘ghost temple’ to the open sky: The Red House in 2006-2007

When Chang opened the drag bar Café Dalida in late 2006 as the second business to enter the Ximen Red House Plaza, he said, it evoked Lanruo Temple, an abandoned ghost temple in the popular Hong Kong fantasy romance movie “A Chinese Ghost Story” (1997). With the exception of Little Bear Village—the plaza’s first gay business, which once occupied the space where Café Dalida’s restrooms are today—most of the storefronts had been boarded up for years.

The Ximen Red House Plaza is a two-story complex on the south side of the Red House, one of Taiwan’s most well-known and well-preserved historic landmarks constructed by Japanese colonizers in 1908. As Taiwan transitioned through periods of change, so did the buildings’ functions. Originally a dry and wet goods market under the Japanese, the Red House later became a playhouse and movie theater, reaching the peak of its popularity in the 1950s and early 1960s. However, in the 1970s, as movie theaters with newer technology and shopping districts opened just a few blocks north in the modern-day Ximending Shopping District, the Red House began to fall out of public favor.

It consequently began to show second-run movies and pornographic films, beginning the building’s history as a gay cruising spot. “In the dark cinema,” a 1996 United Daily News article recounted, “male homosexuals would touch, kiss and even engage in indecent acts, turning the cinema into a meeting place for homosexuals, scaring away the real moviegoers. Over time, everyone knew the Red House as a gathering space for the gays.”

But after decades of disrepair and gradual decay, when rain would seep into the cinemas, even the gays scattered and the Red House officially closed in 1998. A fire in 2000 destroyed half the plaza’s stalls as well as the Cross Building behind the Red House, and near-complete silence fell on the entire plaza. Despite the Taipei city market administration’s attempts to reinvent the space as a youth-centered shopping complex reminiscent of Boston’s Quincy Market, vendors would close as quickly as they opened, fading in the race for urban growth and shifting of commercial centers in Taipei.

Part of the plaza’s lack of commercial viability was a result of its physical setup. Although it has three separate entrances, the Ximen Red House Plaza is almost entirely enclosed and hidden behind the Red House. Standing on one side of the complex, there is no sense of what might be on the other. But in 2006, the hidden nature of the space is exactly what appealed to the first gay businesses to open here, nested deep in the plaza’s palms with the Red House and the two-story plaza towering over and shielding them from the world.

I met Chang for a mid-afternoon interview at Café Dalida, just as some of the other stalls began to set up outdoor tables and chairs. Disco balls and Edison lightbulbs peep out between a canopy of hanging ferns and spider plants at different levels. On Chang’s Facebook profile, he lists his occupation as gardener, and indeed, some afternoons he can be seen caressing and watering his plants—all real, he is proud to let me know. Wind chimes, also stowed away in the canopy, rattle like applause whenever a breeze carries through the plaza. All the bars in the plaza are outdoors but Café Dalida’s dense, jungle-like appearance stands out.

Chang and other early entrepreneurs found the low-rent spaces by pure coincidence or from friends. “The conditions were too perfect at that time,” he explained. The upstart costs were minimal due to the area’s longstanding under-utilization. Moreover, the Red House was conveniently located next to a Mass Rapid Transit (MRT). “Since we still harbored a fear of being outed, the location was just close and far enough from the rest of society,” Chang said. “This was our own hidden kingdom.”

Following in the footsteps of Little Bear Village—the first business to open in the plaza in February 2006, which catered to larger, heavier-set men—Café Dalida opened in fall 2006, frequented at first by many of Chang’s loyal customers and friends from FRESH. By the end of 2006 and 2007, the entire first and most of the second floor of the commercial strip, respectively, were occupied by gay bars, men’s clothing stores and other businesses operated by or aimed at LGBTQ+ people. News of the Red House Plaza spread across the gay community like wildfire.

For Rob Yuchia Lo—a financial reporter, poet, vice president at the Taiwan Association for Human Rights and longtime friend of the Red House Plaza bars—the emergence of the Red House coincided with his personal history. “I had come out in high school, and when the Red House emerged a few years later, it felt as though Taipei’s spatial evolution as an LGBTQ-friendly city coincided with me growing into my own skin,” he told me. Lo went on to write his Master’s thesis at National Taiwan University’s Graduate Institute of Journalism, titled “Living Dreams in Ximen Red House Square: Toward a Civic Space of Gay Community in Taipei,” on this very topic.

Indeed, many of the interviewees in Lo’s thesis emphasized the ways in which the Red House expanded the possibility of life for the gay community at that time.

“It’s not just about having a drink. It’s about exchanging life experiences and gossip, venting frustrations, seeking emotional comfort or even flirting with the next table,” one interviewee said. Unlike the unmarked entrances to gay bars of the past or the temporary nature of cruising hotspots, rainbow flags drape down the inside and outside of the plaza at all times, demarcating this space as safe to discuss everything from your most recent sauna encounter to your frustrations with workplace discrimination without having to look over your shoulder.

“Most other places will say they are LGBTQ-friendly,” Chang said, chuckling. “Here, we say that we are straight-friendly.” In addition to providing a sense of ease for gay men to socialize freely, he emphasized that the plaza has also been able to dispel demonizing myths and stereotypes. Initially, some landlords and existing businesses were hesitant to interact with gay business owners. But with the commercial revitalization brought about by the plaza’s gay bars and lifestyle shops, attitudes slowly began to shift.

When I chatted with street food vendors along the plaza’s street-facing exterior, most of whose stalls share a back wall with the first-floor bars, they were gracious in their praise. One vendor told me how the gay bars encouraged customers to purchase food from the stalls during the pandemic, which enabled them to stay in business.

Gay bar owners like Chang and Hsiao turned the Red House Plaza’s commercial disadvantage—its hidden, out-of-the-way location—into its greatest asset. Here, gay men gradually learned how to become themselves around one another and society writ large.

Twenty years of reverie later

At the end of his thesis, published in 2010, Lo posed a question: Is the Red House Plaza a space of resistance and social liberation for the gay community or just the illusion of liberation? Is the plaza any more than a row of bars where gay men get drunk and meet friends?

I met Lo in The Garden, a bar in the Red House Plaza where he not only comes to drink but which he sometimes treats as an office and meeting room. I fired the question back at him, curious how he’s reflected on the last 15 years since his research. When I think of Lo, “effervescence” comes to mind. A self-proclaimed “auntie”—a term used within the gay community to refer to older gays—he cracked jokes and laughed with his entire body within the first few minutes of our conversation. From a distance, in his circular, thick-rimmed glasses and tucked-in collared shirt, he looks like a buttoned-up professor, but in conversation, he leans back in his chair, rolls up his sleeves and openly declares that gay men will always look for sex.

“I used to think that the Red House Plaza was just a social performance, that people were here to make a claim about one’s social status or how mainstream you were,” Lo said, referring to a thesis chapter on the rituals of belonging and bodily performance he observed in the plaza. I thought back to my first times speeding through the Red House myself—in the name of research—and feeling the heat of glances and gazes in my direction, eyeballs scanning me up and down.

Indeed, the Red House Plaza Lo described in 2010 feels reminiscent of today’s. During his fieldwork, he noted how men would often refer to it as the “Animal Planet channel,” with each bar serving a different gay subculture: bears, wolves, pigs, monkeys. A friend who has been a patron for the last 10 years corroborates the idea; different bars serve different socioeconomic classes (“Check the prices and how large the drink glasses are”), identities (migrant workers at Mudan, Indigenous peoples at Casa) and subcultures. Across the plaza, crowds of friends nestled into deep-bellied laughter, with each discrete crowd appearing homogenous in more than just their sexual orientation.

Look in any direction, and you will likely encounter a group of gay men sporting a “mainstream gay aesthetic” that many associate with the Red House Plaza: neutral-toned tight-fitting clothes, a tight fade or buzzcut, the ridges of an athletic or muscular build toned under the lights, long white socks pulled up just under the quads. A friend once told me that they avoid the Red House Plaza because they “do not want to feel worse about their body image,” judged by the prowling eyes around them.

To me, these glance-overs have never felt as carnivorous as they may be in a club; rather, we seem to scan for evidence of ourselves: body shapes and clothes and affectations that indicate how “gay” someone else (and in turn, we ourselves) might be, how much someone blends in or stands out. Once at the Red House, I tied up the bottom of my thrifted, oversized button-down shirt into a bow, creating a crop-top to relieve myself from the humidity. “No one wears their shirts like that here,” someone said in passing, before a friend corralled me toward another table.

Some have found belonging, others have felt ostracized. Businesses have opened and folded, parties have been come and gone. With the Red House Plaza as its nucleus, the number of gay businesses in Ximending have expanded, with BDSM-themed bars, karaoke bars, ever-popular shower shows and gay saunas. Bars across the city have begun to incorporate drag shows, owing largely to the precedent Chang set at Café Dalida. With more bars offering similar programming and events, however, competition has stiffened and business has noticeably dispersed from the Red House Plaza to eastern Taipei and other sites.

I wondered if this was it then. Gay men, no longer hiding in basements, will replicate these social performances of belonging and cackling across the reverie of gay nightlife. Businesses will mimic each other’s themed nights and music choices in the name of more options. In the throes of late-stage capitalism, we’ll find our way to new bars once old favorites close. A few interviewees told me about Yanji Street, once a row of popular gay bars that by 2021 had all closed down as a result of noise complaints. New restaurants and broken-down construction sites have left no physical markers of these bars, memorialized in the drunken memories of those who frequented them.

So does the Red House Plaza still matter?

The invisible hands of the government

If you search the Red House’s official website, managed by Taipei’s Department of Cultural Affairs, for the word tongzhi—the term typically used to refer to gay men today—only two results return. One is from the centennial anniversary special exhibition site: “Today, [the Red House] is a social magnet and destination for overseas tourists, where stars hold concerts, dance troupes give performances, and gay pride parades are held.” Another is from the “Area Guide,” which includes a small blurb about each of the major Red House venues. Here, the plaza is described as a gay cultural area well-known across Asia.

The Red House Plaza is under the jurisdiction of the department and another government agency, the Market Administration Office (MAO), which wield the power to decide the longevity of the plaza as a gay space. The MAO leases stall space as publicly-owned land to the market vendors housed in the building prior to the 2001 fire. The bar owners and businesses do not have an official lease. Rather, they work in “partnership” (hezuo) with the former market vendors, who have full agency over the rental price paid by the bar owners. Indeed, I heard about some rents that stayed the same for 10 years and others that doubled.

Many bar and business owners, who wished to speak anonymously on this subject, recognized both their privilege to continue operating in Ximen—one of the most expensive real estate markets in Taipei—due to the public ownership of land as well as their invisible status, their businesses at the mercy of their “partners.”

To this day, the MAO maintains a cautious distance from the plaza’s LGBTQ+ identity. Once, when the Department of Tourism—one of the most queer-friendly and supportive government agencies—arrived to record a video introducing important LGBTQ+ communities and spaces in Taiwan, the MAO obstructed the process, fearful that defining the plaza as a gay space would make it more difficult to attract future vendors—presuming that one day, these gay bars will cease to exist.

Meanwhile, the Department of Cultural Affairs’ Taipei Cultural Foundation (TCF) owns the outdoor space in the plaza. Every month, it collects 55,000 New Taiwan Dollars (NTD, approximately $1,550), from the Ximen Market Autonomous Association, comprised of the vendors who lease to the gay bars, in exchange for allowing all the bars to set up outdoor tables and chairs. Various bar owners have mentioned that while the rental amount has not risen much over the years—Lo and Wu both wrote in 2010 that the monthly rental fee was 50,000 NTD—other management fees and costs have emerged, and it isn’t always clear to them which entity collects these fees.

“When there were hardly any people here, [the Department of Cultural Affairs] didn’t bother you, but once business picked up, they started charging rent,” a bar owner mentioned, expressing frustration when recalling the agency’s eagerness to take a share of the profits from a New Year’s Eve Party many years ago.

Lee Chih-yung, the director of TCF’s operations in the west of Taipei, expressed enthusiasm for supporting the LGBTQ+ community as a part of the Red House’s Environmental, Social, Governmental (ESG) initiatives. “In providing cultural nourishment and enrichment, our goal is for people to realize how important it is to protect the different cultures and social groups that influence what Ximending, Taipei and even Taiwan have become today,” he said. “Gender diversity is an important part of this mission.”

When I first arrived in Taiwan last fall, I was struck that the Red House hosted two back-to-back exhibitions to coincide with Taipei Pride and Transgender Awareness Week, in partnership with several LGBTQ+ NGOs: one on the legalization of transnational marriage, another on transgender photography and visual arts. The Red House regularly designs its own exhibitions, including an anniversary celebration each December, and when I asked if the Red House would endogenously create one on LGBTQ+ issues, Lee was quick to respond:

“Of course!”

As he gave me a personal tour of the Red House, Lee pointed out the history behind each architectural feature and the intentionality behind each vendor housed within the building. All are small, up-and-coming Taiwanese brands that do not have physical storefronts elsewhere and make some cultural or social contribution: repurposing recycling electronics, uplifting indigenous weaving arts, supporting small factories. TCF also co-sponsors and provides space for the annual Taipei International Rainbow Cultural Festival with TAIWANIZE, an LGBT-owned clothing brand that has long had a stall in the Red House’s Cross Building. The festival takes place during Taipei Pride weekend, with DJs and go-go boys taking over the stage and LGBT-owned small businesses setting up shop all over the plaza.

Caught between governmental agencies that seemingly preclude and respect its status as a gay public space, the Red House is a live barometer of how widely LGBTQ-friendly policy and sentiment extend: Does the government simply see the LGBTQ+ community for its spending power and tourism appeal or is the government truly willing to support LGBTQ+ culture as part of Taipei’s geography and social history?

“We do want to be recognized,” Chang said, “not be overlooked as we have been for decades.” Since he opened Café Dalida in 2006, only two of 20 candidates over four mayoral elections visited the Red House Plaza as a part of their campaign trail, he said: Su Tseng-chang of the liberal Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in 2010 and Huang Shan-shan, an independent candidate, in 2022. Neither won election.

In the more conservative Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT)-led Taipei city government, Chang and other bar owners often feel as though they have no one to turn to for meaningful political support. Recently, Café Dalida has been forced to stop hosting drag shows due to noise complaints from nearby residents—which, to me, eerily hearkened back to the legacy of the Yanji Street bars.

Chang has two wishes: to be able to see and perform drag until he’s 70 years old and “for the Taipei city government to proclaim, with honor and glory, to the rest of the world that this is a sacred place for the LGBTQ+ community.”

Futures of care

Taiwan AIDS Foundation’s outpost on the second floor of the Red House, affectionately called Gisneyland, is not a government-subsidized tongzhi health center. “But out of a conviction that a gender-diverse space like the Red House needed a health center, we rely entirely on donations to maintain our outpost,” Don Lin, a marketing manager and social worker at the organization, told me.

Founded in 2005, the foundation is one of a wide network of NGOs that provide HIV testing services, public education, social work and care for HIV+ patients and drug abuse workshops as a means of driving Taiwan toward an AIDS-free future. In line with the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), the Foundation is working toward the “95-95-95 Target,” according to which 95 percent of all HIV-positive individuals are diagnosed, 95 percent receive antiretroviral therapy (ART) and 95 percent of those treated achieve viral suppression by 2030. The Gisneyland Red House outpost is one of three brick-and-mortar health centers the foundation manages across Taiwan—the other two are in Hsinchu and Chiayi cities. Each year, it conducts 3000 to 4000 tests, with a current positive rate of 1.8 percent. In addition to HIV and other STD testing as well as the care work that follows, the Red House outpost is beginning to offer psychological support and counseling.

When Little Bear Village opened in 2006, the foundation quietly occupied a table at the bar every Wednesday for about three hours, rain or shine, to offer free, anonymous rapid HIV testing services. The HIV/AIDS infection rate was at one of its peaks at that time, largely as a result of intravenous drug use. In 2012, the owner of Little Bear Village encouraged the foundation to take over the space upstairs. After Little Bear Village closed, the outpost moved in 2018 to its current location above The Garden: a cozy room decorated in light pastels, siphoned off by curtains for the anonymous services, with the word GISNEYLAND in Disney-esque font faintly glowing over the crowded bars below.

“No matter how arduous or expensive it may be to maintain that space, we feel the need to persist,” Lin Yin-han, a vice secretary general at Taiwan AIDS Foundation, said. Part of the persistence has to do with the lasting stigma of AIDS in and outside the LGBTQ+ community. When I asked if attitudes have changed significantly in the 20 years of the foundation’s operations, Chief Operating Officer Sandy King sighed.

“In terms of generations, yes,” she said, describing ways in which campus outreach and school-based events have gradually shifted younger generations’ perceptions of HIV-positive people. “But as a whole, there has been little change. The public still tends to believe in gossip and negative media.”

And although the LGBTQ+ community as a whole has gained more social acceptance over the years, AIDS patients have yet to catch up even after four decades. King described a recent incident involving DCard, a Taiwanese anonymous bulletin board where someone posted about a colleague’s HIV-positive status. When the subject spat at work, “everyone got scared and wanted to get him fired from the company, thinking it would spread.”

The Taiwan AIDS Foundation places equal importance on its educational campaigns to destigmatize HIV/AIDS, aimed at society writ large, and its testing centers. The Red House is not only its most-utilized testing center across Taiwan but also normalizes HIV/AIDS testing and services as an everyday aspect of LGBTQ+ life. Inside the outpost, trained social workers gently ease visitors’ anxieties using the 15 to 20 minutes between test and result to patiently provide information and chat. Just outside, people drink, play games on their phones and get their nails done at the salon next door. With HIV/AIDS having gradually become destigmatized in the minds of LGBTQ+ people, getting tested feels as routine as grabbing a pint.

The question in Lo’s thesis hides behind a layer of facetiousness. For the Red House to exist and be frequented by thousands every week is significant. After all, here is Café Dalida, the “birthplace of drag,” where Nymphia Wind—the most recent winner of RuPaul’s Drag Race Season 16—and so many of Taiwan’s most well-known drag queens started to perform. Here is where Tim Lu, a hospitality professional and former bar manager in the plaza, found a community when he first moved to Taiwan from the United States as a young adult in the mid-2010s. “It was my safe place,” he said. “Here, I found guidance from people across generations, who encouraged me to experiment to find myself.”

In his cultural memoir Gay Bar: Why We Went Out, the writer Jeremy Atherton Lin writes that “a gay bar can be a repository for all the extra that doesn’t fit into other spaces.” Of course, there is no perfect, all-inclusive repository, and the Red House may be far from a perfect symbol for the gay, let alone LGBTQ+, community in Taipei. But as a meeting ground for gay men with one another and the rest of society, the Red House Plaza continues to be an entry point for some gay men to realize that their “extra”—whether baggage or flamboyance—need not feel estranged.

At first, when I asked Lo the question from his thesis—whether the Red House Plaza represents social liberation or is merely a façade—he took a moment to think. He looked outside the window onto the plaza just as it began to open at dusk, the evening’s first customers pulling out metal chairs that screech against the pavement. We were two bottles of beer deep each, having spent most of our conversation laughing at the social dynamics of the plaza and recounting stories of various gay bars we’d been to.

“I’m not as cynical anymore,” he finally said. “Now, I think the question presents a false choice. Rather than expect society to liberate us, we have to liberate our mindsets and realize we have nothing to be sorry or guilty for.”

In a society in which 50 percent of the population looks down on public displays of affection between gay men, as a recent survey conducted by the Taiwan Equality Campaigns reports, gay men’s chain jewelry and sweat catch the glow of fairy lights gleaming above, pitching glints of pink afterglow and desire across the plaza to men they may or may not kiss later that evening. Where EDM circuit remixes collide with Kylie Minogue, gay men find safety as much as the thrill of new possibilities. When I walk through the Red House now, I am not dodging the eyes from the closest tables, rather scanning the rows for friends or just enjoying the breeze on my way to the noodle shop I enjoy around the corner. Like so many other gay men, I’ve gradually learned to become (if only a little less self-conscious) in the space.

“That’s why we gather here at the Red House,” Lo said. “To bear witness to how we’re liberating ourselves and becoming those people we always imagined ourselves to be.”

Top photo: Lee Chih-yung stands in front of the Red House, the programming and continued development of which he has managed since 2021