LINCANG, China — Deep in the mountains of southwestern China, where tea was likely first discovered, a trail begins. Over the course of a thousand years, it has been carved step-by-step through some of the world’s most diverse and rugged terrain, traversing the lush tropical forests of what is now Yunnan province—a botanist’s veritable playground—and up into the Himalayas, through treacherous river gorges and snowy mountain passes. The carving was done by mabang, trade caravans comprised of humans, horses, mules and yaks that carried daily necessities such as salt, sugar and medicines as well as luxuries like textiles and cigarettes. But most important, they carried tea.

Compressed for easier transport, it was a vital source of nutrition for those living in the harsh climate of the Tibetan plateau. For tea-producing regions, it was a critical means of obtaining Tibetan warhorses that would help distant dynasties administer their borderlands. For both regions, it was the centerpiece of social interaction. Tea begat trust and trust begat trade, the virtuous cycle of which built the route we know today as the Ancient Tea Horse Road.

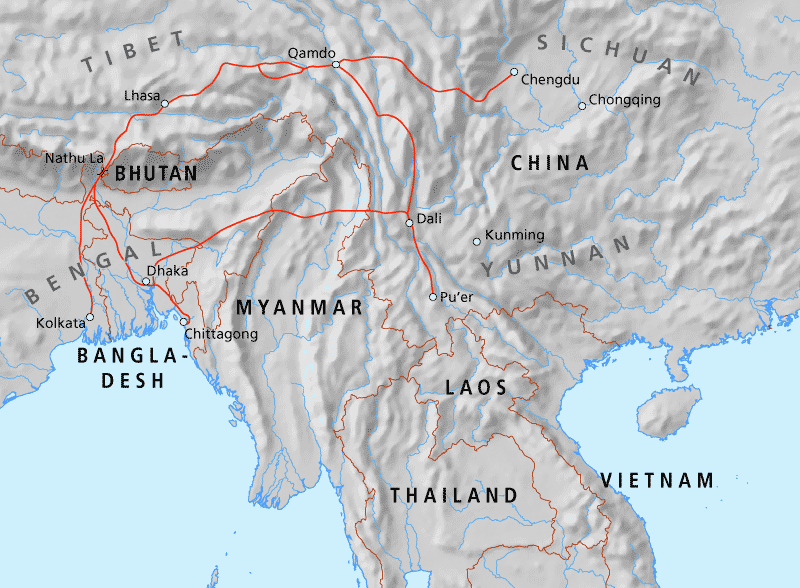

In fact, it was more a network of trails than a single road. Its branches diverged and converged, even extending down to Southeast Asia and west to Nepal and India. It remained a lifeline across the region well into the mid-20th century until the advent of motor vehicles led to its disuse and disrepair.

But in recent decades, it has been revived, no longer for trade but tourism. Any locale remotely connected to the old trade route is trying to cash in. Plaques go up declaring villages part of the Ancient Tea Horse Road. Local governments decorate town plazas with statues of muleteers and pack animals. Even entire cities are renamed. For centuries, puer tea was currency along the route. Today, it would seem, it still is.

In the city of Lincang, along one of these offshoots, is the Ancient Tea Horse Village, a tea-themed development complex with residential apartments and commercial shops. Although it has less name recognition than Puer and Xishuangbanna, Lincang prefecture produces roughly a third of all tea in Yunnan, and the local government is trying to raise its profile with projects like a tea museum and the Ancient Tea Horse Village. Apartment sales have been brisk. All units sold out on the first day of sales before construction was even finished—mostly for property speculation—and prices have doubled in the last four years. Unsurprisingly, I’ve never seen anyone living in the apartments. Similarly, the commercial spaces are all teashops, outfitted with lacquered slabs of tree trunk and girls sitting behind them pouring tea. But I’ve never seen anyone buying tea.

Zhu Xian’e, who goes by Fairy, sits in Eight Points Teashop at just such a tree trunk. She’s the spitting image of her older brother, Zhu Hong, the free-spirited mayor of Bangdong village where I live, but with a fairer complexion and shorter hair. Whenever I pass through Lincang, three hours from Bangdong by car, I stop by Fairy’s shop for a spot of whatever’s brewing. Today, it’s hongcha.

“Come have some tea!” she says when I walk in the door. She’s always in the middle of brewing something, so I sit down to some steaming Yunnan black tea, its liquor deep red in my cup. Black tea in the West is so named for the dark color of its leaves. In China, however, it’s called hongcha, or red tea, because of the hue of its liquor. People in most of the world think of black tea when they think of tea; indeed, about 90 percent of all tea consumed is black. Regrettably, much of the world also thinks of tea bags rather than loose leaf, the former considered an abomination by most Chinese: the instant coffee of the tea world.

Besides black tea, consensus holds, there are five other types: white, yellow, green, oolong and dark teas like puer. Incredibly, all come from the same plant, Camellia sinensis, while their unique flavor profiles are determined by plant variety, terrior including soil and climate, and, most significant, processing method. Simply put, processing determines the level of oxidation in the tealeaf, which turns it dark, like the browning of an apple slice when exposed to air. White and black teas bookend the spectrum with zero and full oxidation, respectively. Yellows have minimal oxidation followed by greens and then oolongs. Dark teas, like puer, are the exception because they actually undergo fermentation.

During the six-months it typically took caravans to travel the Ancient Tea Horse Road, puer tea would continue to ferment and oxidize en route, enhancing its taste upon arrival. If stored properly, older puers are said to taste better, much like wine, and can be worth large amounts of money. That led to widespread speculation in the early 2000s and a tenfold increase in prices, some teas fetching tens of thousands of dollars per kilogram. That is, until the bubble burst in 2007.

“When are you coming back to Bangdong?” I ask Fairy as she refills my cup. I tap the table twice with two fingers in thanks.

“Jiujiu finishes swimming lessons next week,” she tells me. “Then we’ll come back.” Jiujiu is Fairy’s eight-year-old daughter. She sits in the corner of Eight Points Teashop doing homework, surrounded by orchids and strange stones. Under the stairwell, water trickles down a mossy rock into a small coy pool. Jiujiu’s classes have ended for the summer, but in China homework never does. When she started elementary school, Fairy moved with her from Bangdong village to Lincang in order to enroll her in a better school. Jiujiu’s father helps manage the Eight Points plantation in Bangdong village while Fairy tends to the shop in the city. “Is it time for a break yet?” Jiujiu complains to her mother, tired of math problems. “Can I play on your phone?”

Fairy seems to have grown tired of the hongcha and dumps out the leaves into a trashcan. She pushes a button on her water kettle, prompting a spigot to hum around and fill it. It stops automatically and the pot begins to heat to a precise 85 degrees. Meanwhile, she gets out a brick of puer.

Most puer comes in a hard round cake, compact like a discus and exactly 357 grams (13 ounces). When tea was transported on the Ancient Tea Horse Road, cakes were typically stacked in sevens (2,499g) and wrapped with dried bamboo husks as waterproofing. These were packed in groups of twelve (30kg), of which a mule would typically carry two (60kg), making it expedient for caravan leaders to calculate loads. But Eight Points Tea is not carried by mules; rather, Fairy, her husband and brother are trying to build a modern brand, so it comes inside sleek, professionally designed packaging in bricks of 200 grams—the perfect gift. Fairy begins to pry off layers of dried leaves with a tea pick—what appears to me as a glorified screwdriver—and lets me smell them. Suddenly, I’m sixteen again mowing summer lawns.

“This is raw puer,” she tells me as the kettle whirs to a steam. “Raw” puer is processed and left to age naturally whereas “cooked” puer is fermented for over a month to mimic the taste of a slow-aged raw puer. Fairy washes our teacups with the hot water and steeps a first brew of the tea in order to “wash” it as well. This she dumps out, a brew fit only for an enemy. But with the second infusion she fills my small cup, her movement poised and practiced, yet graceful and effortless: wu wei (无为) in action.

I tap twice and take a sip. It tastes like stable hay soaked in spinach juice—in the best of ways—and goes down slightly bitter. My tongue turns hairy and rubs rough on the top of my mouth. But this was only the second infusion. Yunnan’s broadleaf puer can be steeped over and over and over, upward of 20 or 30 times, and Fairy would keep my cup hot and full for the afternoon. “A tea’s taste changes over time,” she tells me sometime between the third and thirteenth infusion. “With each steep I’m trying to bring out its uniqueness in that moment.” She eyes its color and wafts the lid of the teapot under her nose, clues in the quest for a perfect cup. “Tea is a journey.”

* * *

Puer tea from Bangdong was on a journey long before it reached Eight Points Teashop. On the outskirts of the village, hundred-year-old tea trees tower over me, gnarled and unruly, spread across the terraced mountainsides. There are no tidy hedgerows here. The broadleaf variety—Camellia sinensis assamica—thrives in tropical areas like Yunnan and India and has been cultivated for hundreds if not thousands of years. One tree in Lincang prefecture, known as “the Tea Forefather,” is reported to be 3,200 years old.

It’s spring harvest and my 60-something neighbor in Bangdong, Li Wenying, introduces me to the first steps of tea’s journey. She sports a denim baseball cap with canvas camouflage shoes and climbs spryly up a bamboo pole into the branches of a tea tree. Her hands move swiftly, finding a sprout, pinching it between her thumb and index finger—both protected with bandaids—and then rolling the green leaves into her palm. Her work is rhythmic—grab-pinch-roll, grab-pinch-roll, grab-pinch-roll—as her hands waltz down the branches. But it is as much science as it is art. While she picks, she also prunes the tree for next season’s flush, plucking off leaves and discarding them on the ground. She knows exactly where new leaves will sprout. I had asked Grandma Li, as I call her, if she would teach me to pick tea and today my lessons begin.

Admittedly, I am nervous. This is Grandma Li’s livelihood, after all. In Bangdong, money does grow on trees—about 80 percent of residents’ income is from tea—and I’m not keen to waste it for the sake of a learning experience. Moreover, this is the spring crop, the most valuable harvest of Bangdong’s five picking seasons at roughly $50 per kilogram. The tree has been sucking nutrients from the soil all winter so its first flush is chock full of antioxidants that may prevent cancer, and could help you lose weight, and might make you live longer. It also tastes better.

Thankfully, this is not my first time. I once took a group of students to pick tea in the hedgerows of Hangzhou, in eastern China, so I know well the secret to tea picking: one bud, two leaves. I waltz in with confidence. Grab. Pinch. Grab-pinch-pinch. Ro-o-o-o-o-ll. My fingers stumble over the gnarled branches, like two left feet.

“No, no, no!” Grandma Li cries out, when she sees the green leaves I’d strewn on the ground. “These leaves are good!” she says, climbing down from her perch and picking them up one by one. She’s not angry, but clearly my discards were valuable. Evidently the Yunnan broadleaf is different from the small leaf varieties in Hangzhou, so one bud, two leaves does not apply; rather, four or five leaves are included on the stem. “It is now 10 o’clock Beijing time,” a digital voice from her pocket interrupts my profuse apologies. It’s to be a long day.

By afternoon, I find my rhythm but dark clouds have been gathering overhead and shortly after “17 o’clock Beijing time” something between a mist and a rain spills out on the fields below. We scurry home. The hillsides bustle as tea pickers rush to protect their freshly plucked leaves. Men strap bulging feed sacks to overloaded motorcycles and ride precariously on the mountain trails. A group of women, day laborers from another village, heave their loads on their backs and secure them around their foreheads with rope and cloth. A crosswind spits raindrops in their faces and carries their chatter up the hillside.

Back home, Grandma Li places her bloated sack on the scale: 10.55 kilograms (23 lbs). Were she selling to a local processor, she’d earn about 200 yuan, or $30, for her leaves. But her family does all processing in-house—buying fresh leaves from neighbors as well—and then sells all over China to teashops like Eight Points. My leaves weigh in at 1.4 kilograms—a mere $4. All in a day’s work. Thankfully, Grandma Li recognizes it’s not my fault. “Women are just better tea pickers than men,” she consoles.

Despite my poor performance, Grandma Li insists I stay for dinner—it’s only another pair of chopsticks after all—and afterward we sit with her husband and son drinking tea by the fire pit. There’s little ceremony to the blackened teakettle simmering in the coals. The kitchen as a whole is crude—cracked concrete floors and walls of leftover asbestos roofing. There are no dainty teacups or trickling fountains here. Leaves have been steeping in the kettle since before dinner and the brew pours out yellow and thick. Even after I top it off with hot water, it goes down bitter. But there is a sweetness to the moment: a day’s work behind us, full stomachs and a brief respite with family before a long night ahead.

Soon, sweat will be pouring down her son’s face as he constantly turns the leaves in a wood-fired wok, scoop after scoop, batch after batch. Then her husband will knead the leaves, giving them their flavor and shape, before Grandma Li scatters them over bamboo mats to dry overnight. Last night, father and son worked until daybreak, while Grandma Li rested up for the day’s picking. Tea is a family affair, and by morning, the 150 kilograms of leaves they bought today would cook down to about 30 kilograms of loose-leaf tea, ready to be steam-pressed into puer cakes and traded for Tibetan warhorses or served at Eight Points Teashop.

I sip again from my steaming glass and think to myself: “This tea is just right.”

* * *

Freshly picked and withered tea leaves crackle as they are “fixed” over a wood-fired wok to prevent further oxidation

In the coffee industry, assessing quality, or “cupping,” is an objective process. Experts have developed standard criteria and a 400-point scale such that around the world any certified expert, known as a Q grader, will evaluate the same cup of coffee “within five points of one another,” one told me. Tea, however, is subjective. Fairy and any teashop owner will tell you it depends on too many factors and the personal preferences of the tea drinker. Tea, after all, is a journey.

Lacking any consistent methodology for evaluating tea, Yunnan’s $10 billion dollar tea industry runs on trust. Sophisticates and casual tea drinkers alike depend upon trust in their local teashops, which depend upon trust in the wholesale tea bosses. Each year, these bosses on China’s east coast head to the hinterlands to sample tea harvests at origin and restock their inventory of greens, blacks and puers. Eight Points Teashop, in reality, then, isn’t actually a teashop; it is a hospitality space and branding tool to receive and build trust with these tea bosses, the Q graders of the tea industry. They sample tea after tea, visit plantations of local suppliers, and buy wholesale to ship to Beijing or London or Istanbul. That is how Eight Points makes money and why I can sip tea free.

The sophisticated network of shipping logistics and online marketplaces that makes this possible is a modern Ancient Tea Horse Road. Tea farmers, once in the most remote mountain areas, are now connected to the global economy via modern trade caravans like Shunfeng express shipping and Taobao e-commerce. And, as we’ve seen, prosperity from the tea trade extends to a burgeoning domestic tourist industry and even real estate. Tea is money, which means a better life for Grandma Li, Fairy and Jiujiu.

But perhaps more remarkable still than tea’s material benefit is what it can do for the soul. I once stopped at a historic outpost where the original stones still pave the old tea-horse trade route, worn smooth by the steps of man and mule. There, in a small teashop, sat ten teacakes behind a lacquered slab of tree trunk, each scribed with a single character:

At a guest’s arrival, your heart should be warm;

until their departure, their tea should not cool.

Whether sipping at Eight Points Teashop with Fairy or around the fire with Grandma Li, more pleasant than any pour of tea is what overflows from the heart: hospitality, generosity, kindness. Humanity, at its best, in a cup.