PARIS — I pass the Bataclan theater almost every day on my way to and from my apartment. It’s on the next block, sandwiched between the post office and a cocktail bar. It’s also the site of the bloodiest massacre France has experienced in recent memory, when gunmen stormed the theater on November 13, 2015, killing 89. Nearly three years on, young people crowd in front of the establishment on a near-weekly basis, and spill out of the recently renovated bar next door. The Bataclan remains open not as an official memorial but the music venue it has been since the early 1970s.

In March, the French rapper Médine, who is Muslim, released a new track, “Bataclan”—an ode to his longstanding dream of playing at the theater. And in October, he’ll do just that—with two scheduled shows that quickly sold out. That is, if all goes as planned: over 30,000 people have signed a petition launched by the far right to demand the concert’s cancellation. The signatories denounce the rapper’s controversial lyrics that they allege would violate the memories of those who lost their lives that night in 2015. Médine’s detractors cite his songs that take issue with France—one, “Don’t Laïk,” has received particular attention. The title of the song—released a week before the January 2015 shooting at the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo—is a play on “don’t like”—as in social media—and laïcité, or French secularism.

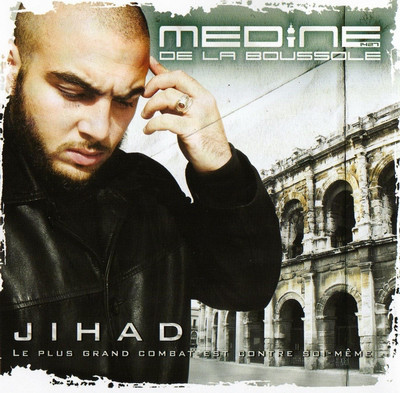

Yes, in France, rappers rail about secularism. To the consternation of his far-right critics—but also the so-called Republican Left, notably a movement called the Printemps Républicain, which I’ve explored in several newsletters—“Don’t Laïk” calls on listeners to “crucify laïcards like in Golgotha.” That’s a reference to hardline secularists; while laïcité as a principal is widely accepted, those considered laïcard defend a strict, expansive interpretation of the term (the mayors who attempted to ban burkinis on beaches in the summer of 2016, for example). The title of one of Médine’s albums, Jihad, has understandably raised eyebrows—although the subhead on the cover says “the greatest combat is against oneself,” echoing the notion of internal struggle that many Muslims use to define the term.

Those calling for the show’s cancelation cite those lyrics and others as evidence of his complicity with radicalism, despite the fact that the rapper has routinely condemned Islamist violence. He considers his lyrics a satirical jab at what he described in a 2015 interview as the French refusal to hear Muslims’ criticisms of laïcité: “I absolutely wanted to talk about the way a Republican value like laïcité is manipulated today, even though, in its spirit and letter, it is designed to unite people,” he told the magazine Les Inrockuptibles.

The Bataclan’s organizers have repeatedly insisted that Médine will perform, while his supporters decry an attack on free expression. And although his detractors on the right are demanding the show’s cancelation, their counterparts on the left have argued that censorship would only make him a martyr—while also questioning the Bataclan’s judgment in booking the show, calling the theater a “place of memory.” The government, for its part, hasn’t excluded the possibility of calling off the show; Interior Minister Gérard Collomb said that “anything that could trouble public order can, within the limits of the law, find itself banned.”

The Médine controversy is the latest case study in the ongoing and intensifying debate over the fate of Republican ideals, from laïcité to a certain vision of free speech, since 2015. And while similar incidents before it—from Mennel Ibtissim, a singing contestant on TV show “The Voice” who was pressured to leave the show, to Maryam Pougetoux, a student-union representative who wears a hijab—have taken place in the media sphere, they feature prominently in the conversation about young Muslims, and how the public education system can ensure that students adhere to and actively defend French values.

Living side by side

In past newsletters, I’ve addressed the previous government’s attempts to double down on the promotion of Republican values, and particularly laïcité, in the aftermath of the 2015 attacks at Charlie Hebdo. That was largely in response to the several hundred students nationwide who refused to participate in a moment of silence honoring the magazine and the victims of the attack—or, as certain policymakers, observers and teachers recall with particular vitriol, the students who said they weren’t Charlie. More than three years later, those marginal incidents are etched onto the national consciousness, and continue to inform policy. The Education Ministry, for one, has multiplied the number of entities and advisory councils tasked with promoting and enforcing laïcité, built on a zero-tolerance approach for what the education minister, Jean-Michel Blanquer, has described as “challenges to laïcité.”

A series of recent prominent studies paints a complex picture of student attitudes toward laïcité; the interviews I’ve conducted since September with students and teachers further complicate the story. Together, they reveal a disconnect between the media and government’s portrayals of laïcité as in crisis and the reality on the ground.

In June, IFOP, a major polling organization, surveyed 650 middle and high school teachers, in collaboration with the National Committee for Laïque Action, or CNAL, an umbrella organization of various associations that focus on laïcité and education. The survey was accompanied by in-depth interviews with 999 middle and high school teachers, based on the survey questions. The project aimed to determine the extent to which French teachers are confronted with the challenges or contestations Blanquer implied were rampant across the country.

The findings, while nuanced, show a disparity between teachers’ sense that laïcité is “in danger”—59 percent of those surveyed worry it is, compared to 72 percent of the general public—and a relatively tempered day-to-day in the classroom. Although 38 percent reported incidents of students contesting the law banning “ostensible religious signs” in schools, for example, 97 percent said those instances are resolved through dialogue. In terms of general contestations of laïcité—from violating the ban to refusing a history or science class on religious grounds—only one in 10 reported regular protests. Seventy-one percent said that tensions around laïcité were linked to national and international news events; 52 percent said “cultural and religious communities mix less and less in France,” compared to 30 percent of the general population.

That last finding is critical, according to Remy-Charles Sirvent, a teacher and the national secretary of the CNAL. “Fifty-nine percent of teachers are worried, but the principal subject of their concern is that communities increasingly don’t mix anymore,” he told me in a Skype interview. “The teachers are worried about laïcité because there’s no intermingling, and different segments of French youth don’t know each other. Instead of living side by side, the goal should be to face-to-face.”

The numbers reflect the overall response rates; nearly all indicators are magnified in low-income, priority-education areas typically home to large non-white populations. For Sirvent, that finding attests to the growing class segregation wracking the school system, with a steady spike in private school enrollment over the past several decades.

The survey’s most glaring finding, he told me, is the 74 percent of teachers who reported to have never been trained to better understand laïcité, even though such training was billed as a significant aspect of the post-2015 response. Teachers who did receive training said they were dissatisfied with the quality and still felt unprepared. That could explain why some of them have trouble distinguishing between typical teenage provocations and a genuine rejection of Republican values and laïcité, he said, which could fuel the perception that those ideals are endangered.

‘Radical temptation’

The blurred line between youthful contestation and an aggressive, anti-system posture—which some contend could be a warning sign for potential radicalization—underscored criticism of an April study conducted by Olivier Galland and Anne Muxel. The sociologists aimed to better understand “the radical temptation” among high school students—with the goal, as they put it, “to address radicalism through the prism of how it might tempt young French.” The study boasts an impressive sample of nearly 7,000 students across France aged 15 to 17, and while it was immediately cited by a myriad of media, others in the field criticized its methodology.

The authors sought to assess which students are most prone to radical views based on their stated religion. They define “radicalité”—best translated here as “radicalism”—as “a series of attitudes or acts that marks a desire for rupture with the political, economic or cultural system, and more broadly with the norms and values in society.” Galland and Muxel described an “Islam effect” based on the finding that 32 percent of Muslim students surveyed are “absolutist” in their faith, which they define as “viewing religion as the only holder of truth.” That contrasts with 6 percent of Christians surveyed and 1 percent among students with no religion. The survey also determined that 20 percent of Muslims said it would be “acceptable in certain cases in modern society” to “fight with weapons in hand for one’s religion,” as opposed to 9 percent of Christians and 6.5 percent of non-believers.

For Jean Baubérot, a prominent historian and sociologist of laïcité, the authors’ very definition of “radicalism” allowed for bias. “What are the characteristics of this ‘system?’” he asked in an analysis of the study for the progressive news site Médiapart, criticizing the portrayal of society’s dominant values as a given that must be accepted at face value, rather than assumptions to be deconstructed. Any criticism of that system, he argued, is “considered an indicator of radicalism.”

Magazine covers and posters honoring Charlie Hebdo at a middle school in Toulouse

Olivier Roy, a professor at the European University Institute in Florence and an expert on Islam and extremism, was among the scholars who criticized the study as biased. Young people of Muslim origin more readily reclaim Islam in all of its forms, and tend to highlight their beliefs faced with the school institution,” he pointed out. French Christians tend to be far more secularized than their Muslim counterparts, he explained, making it difficult to compare the two populations’ attachment to their faith on a level playing field.

Others lambasted the authors’ criteria for determining “religious absolutism,” arguing they were biased against Muslims and failed to consider the social underpinnings of religious identity in France—the way that a sentiment of discrimination, for example, could influence a student’s embrace of religion. Any defense of religion, critics argued, became a qualifier for radicalism.

Whether or not Galland and Muxel’s study is ideologically driven or methodologically flawed, it at least attests to the complexity of objectively assessing attitudes. If a teenager says it’s justified to kill in the name of religion—or that the cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo “had it coming” for caricaturing the Prophet Mohamed—is it ideology, provocation or some combination of the two? Teenagers don’t necessarily engage in nuance, Baubérot added in his response. They like to rebel. Students responded to the survey “within the framework of the institution—they filled out the questionnaire in class, under the eyes of the administration,” which could incite them to be even more provocative. “The study totally ignores this psychological dimension of adolescents, faced with adults,” he concluded.

Is the Bataclan a concert hall, or is it a physical shrine to reinforce the glorification of Republican values? Have certain ideas become so sacred that those who take issue with them are inherently a threat?

Reading the analysis of Galland and Muxel’s investigation made me think of a conversation I had with Nohra Aitu, a teacher I met in Le Havre. She recalled asking her students, the majority of whom are Muslim, where they would go on vacation if they could travel anywhere in the world. “So many of the boys in the class said Syria, to fight with the Islamic State,” she told me, rolling her eyes. “I knew they were just doing it to get a rise out of me.” I asked whether she feared at least one of them might be in earnest. She shook her head. “They like to provoke, and to a certain extent, they feel like the school administration expects that answer from them.”

‘No one cared who she was’

I haven’t encountered any Muslim students who have joked about going to Syria, although many have mocked the idea that, because they’re Muslim, they’re a potential risk. Still, many describe laïcité or the government’s narrative about Islam with hostility.

I don’t consider such statements to be either purely provocative, on the one hand, or explicitly dangerous on the other. Those grievances—about laïcité, the national conversation about Islam or Charlie Hebdo—carry a certain degree of legitimacy. And while teenage narratives must be taken with a grain of salt, high school students are old enough to absorb the world around them. Many are fundamentally fed up with a drone of media coverage and government rhetoric that seems to demonize them, their families and their religion.

That sentiment was on full display during a recent interview I held with high school students in Drancy, in Seine-Saint-Dénis, the low-income department northeast of Paris that’s home to a large Muslim population and has gained notoriety in government and media discourse over the past two decades. “Nobody understands Islam,” Inès, 17, told me. “All we hear about is terrorism, young girls who convert and marry jihadists, and flee to Syria,” she said. “And so France is afraid, and instead of talking about the people themselves, they talk about the fact that they’re Muslim.”

Although Inès, who is Muslim, doesn’t wear a headscarf, she was enraged by the controversy around Maryam Pougetoux. “No one cared about who she was, or that she was engaged for students, even though that’s the most important part of who she is.”

She and her classmate, Sherine, 17—she is also Muslim, and both were fasting for Ramadan—believe that attitude is a product of the law on religious signs. They described the law as “racist,” “Islamophobic” and “humiliating.”

Sherine and Ines at their high school in Drancy, Seine-Saint-Denis

Sherine is feisty and articulate. She is clearly proud of how closely she follows the national conversation about laïcité, which she said is animated by “invented controversies.” Like others her age I’ve met, she expressed a certain reverence for the language that dominates the US conversation about identity politics—intersectionality, white privilege—but remains fringe in France. The national attitude toward headscarves, she told me, is “a degrading and humiliating effort to force Muslim women to undress, to be stripped of their identity.” She denounced the political manipulation of laïcité, arguing it had shifted from its original objective to become an “excuse for Islamophobia.”

I wondered if Muxel and Galland’s rubric would have deemed her responses “radical.”

“Charlie Hebdo is now the national pride, and can say whatever it wants about Muslims, but Dieudonné gets censored,” she said. That was a reference to the controversial comedian Dieudonné M’bala M’bala, whose performances were banned after he was charged with hate speech for his use the “quenelle,” a gesture resembling a Nazi salute. “Either we need to censor everything or censor nothing—free expression needs to be coherent.” She is among many students who cite the comedian, who is a Muslim of Malian origin, as a martyr of French double standards on free speech—not explicitly defending his anti-Semitic gesture, although certainly implying that Jews receive more state protections than other minorities.

Both described a strange memorialization of Charlie Hebdo—with clear parallels to those who see the Bataclan as a sanctuary protesting Médine—in the aftermath of attacks. Elevating the magazine to the pinnacle of French freedom of expression, Sherine and Inès argued, has given mocking Islam—or outwardly discriminating against Muslims—a new form of legitimacy.

“If I say I’m not Charlie—and I don’t feel like I am,” Inès said, “am I suddenly an extremist? When I see their covers, I feel attacked,” she went on. “They’re talking about something important, about my religion.”

I asked if she considers it acceptable to laugh at religion, picking up on a fear I’ve heard from teachers—that some students think religion is too sacred to be mocked. She hesitated first, but responded firmly. “Religion is one of those things we can’t laugh about.”

Rym, 17, a student in Vitry-sur-Seine, echoed that sentiment. “I laugh about everything, really about everything—you can even make fun of me, and I’ll laugh about it,” she told me during an interview at her high school. “But religion, it’s so personal, it’s a subject that you just can’t laugh about.” I asked if that meant free speech should have limits. “I don’t want to say that Charlie Hebdo took advantage of free speech,” she said. “But they’re in the position of power, and that gives them the right to attack and insult Islam. If they have the freedom to attack our values, so should we to attack theirs.”

The outcry over Médine, the deification of Charlie Hebdo, and the rhetoric of an internal threat inherent to Galland and Muxel’s study all help explain why a majority of teachers worry laïcité is in danger despite a relatively manageable situation on the ground. The Bataclan is still a theater and Charlie Hebdo is still a magazine. But they have also become sacred memorials, at least in the national imagination—living reminders of France’s experience with terrorism. It’s worth asking whether or not they can be both of those things simultaneously. Is the Bataclan a concert hall, or is it a physical shrine to reinforce the glorification of Republican values? Have certain ideas become so sacred that those who take issue with them are inherently a threat?

Those questions constantly underscore my research. The climate is one of increasingly radical views that mutually reinforce one another: Elevating Je Suis Charlie has made rejecting the publication—and the set of values it implies—a compelling form of contestation for many French Muslims. That deepens the desire—among the political establishment, the right, and the Republican left—to reinforce those values and pit them against the young people calling them into question. Rinse, repeat, in a shouting match that makes the middle ground seem like more a distant utopia than a feasible goal.