In developing countries, one in every three girls is married before reaching age 18. One in nine is married under age 15. – [1]

In Africa, Nigeria is expected to have the largest absolute number of child brides. The country has seen a decline in child marriage of about 1 percent per year over the past three decades. At this pace, the total number of child brides is expected to double by 2050. – UNICEF[2]

“I was a slave in my husband’s house,” said 17-year-old Rahma. “My pregnancy had complications and my husband sent me back to my parents when I was diagnosed with fistula,” added 19-year-old Fatima. As I listened to these girls share their experiences as child brides, I struggled to keep the at bay as I wondered why on earth anyone would want to deprive these girls of their childhood and livelihoods. Yet, many men (often much older) in countries like Nigeria choose to marry teenage girls, some pre-teens. Forty-three (43) percent of Nigerian girls are given in marriage before the age of 18,;17% are married before their 15th birthday.[3] As Africa’s largest growing population with over 180 million residents, it is anticipated that Nigeria will have the largest absolute number of child brides by 2050.1 In response to this alarming news, the Nigerian government in November 2016 launched a campaign with a pledge to end child marriage by the year 2030. In line with the African Union’s resolution to eliminate the practice in the African continent; Nigeria joins 15 other African countries that have made this a national commitment. Despite this, achieving an end to child marriage is a long way ahead.

Depending on a person’s geographical location and his/her religious understanding, there are several interpretations of what child/early marriage is and whether it is a good or bad practice. Child/early marriage is officially defined as “any formal marriage or informal union where one or both parties are under 18 years of age.”[4] While child marriage affects boys and girls, it is more prominent among, and disproportionately affects, young girls than their male counterparts. But, why are girls disproportionately impacted by early marriage? The answer to this question lies in gender norms and societal perceptions of the value and role of the girl child. While some people find it unthinkable for a man to choose to marry a girl who has not reached adulthood, others see early/child marriage as a solution to societal and economic problems.

As an ICWA fellow, I am interested in learning about the factors that propel families/parents to give their daughters in marriage at a young age. I am also exploring the topic from the perspectives of adolescent girls themselves as I seek to understand what girls in these situations want for their lives and their ability, or lack thereof, to say “no” to early marriage. Thus far, I have learned that child marriage – where it takes place – is not considered as a matter of age, but rather, about physical maturity, i.e. a girl reaching puberty. Interestingly, in most rural communities where child marriage occurs, girls do not know their age. They are taught to understand that once a girl sees her first menstruation, she is ready for marriage. Poverty plays a big part in propagating early marriage. An impoverished family will give their daughter out in order to gain financially from her husband (via bride price and other gifts to the family) and also to have one less mouth in the family to feed. A young girl may accept marriage in order to improve her social condition. As I was told by a female community worker, “Some girls get very excited about getting married. These are girls who each day have to hawk and do various chores to support their families. Getting married [especially to an older man] ensures that they no longer have to live a difficult life. They feel that by marrying the man they will be taken care of as opposed to being with their parents. So, they look forward to it.”

My perception on child/early marriage was recently challenged during a round table discussion in Abuja, 30 Nigerian youth leaders debated the topic of the HIV/AIDs epidemic in Nigeria and how child marriage contributes to the growing infection rates. A medical doctor said, “If God made a 12-year old girl to be able to get pregnant, I’m sure God is not against early marriage.” Dumbfounded and perplexed, I asked the doctor to explain his remark. “Why can’t a girl get married if there are no other options for her in her community?” he asked and then proceeded to explain that while he would not give his teenage daughter out in marriage, he won’t say that he is against early marriage. “What I am against is forced marriage,” he noted. His remarks highlighted the different perspectives through which the issue of child/early marriage can be viewed. Child/early marriage to many people is a result of a lack of viable alternative options.

In Nigeria, child marriage is largely seen as a cultural and religious custom, predominantly practiced in the northern states of the country. While some religious leaders denounce the practice as irreligious, others claim that the prophet Mohammed had an adolescent bride. In fact, the doctor above asked me, “At what age did Mary give birth to Jesus?” He was, of course, implying that Mary was in her teenage years when she conceived and birthed the son of God. While the Bible is rarely used to defend child marriage, the Koran remains a key source for defending the practice of early marriage as it defines the age of maturity (and marriage eligibility) for a girl as puberty.

Why should we care if a man chooses to marry an adolescent girl? To help me understand how a girl’s life is impacted by early marriage, I sat down with a former child bride who is presently undergoing a tough divorce battle. Below is Aziza’s story, translated from Hausa to English.[5]

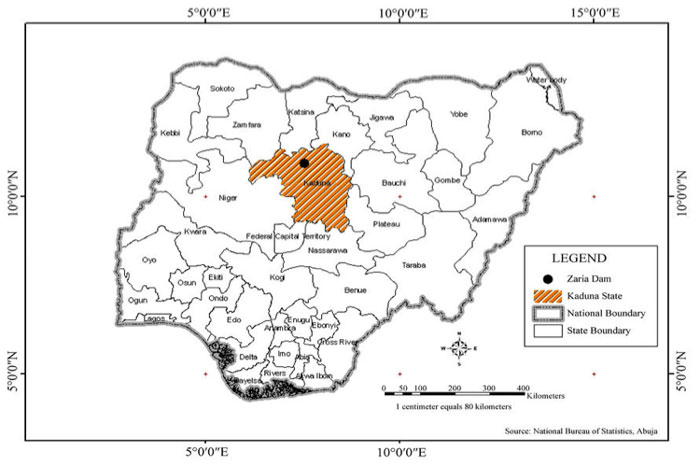

A tall, beautiful, and light-skinned Muslim girl, Aziza was born and raised in Dakashi, Zaria, an “urban-rural” town in Kaduna state in northern Nigeria. She grew up dreaming of one day becoming a nurse or teacher.

Aziza has three younger and two older siblings – one boy and the rest are girls. At the age of 17, while in SS2 (10th grade), Aziza was married off. The marriage was not her choice; it was forced upon her. Her elder sister was also married at the age of 17, got divorced, and re-married again at the age of 21 (though this was not a case of forced marriage). Divorce is a common practice in this community. I first met Aziza during my initial trip to Zaria in September 2016 where I observed her as a participant in a training of adolescent girls as “cascading mentors” for a United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) project. I was opportune to hear Aziza tell her story of being a child bride two months later during the “Launch of the Campaign to End Child Marriage in Nigeria” event hosted by the Federal Minister of Women Affairs and Social Development in Abuja. I was captured by Aziza’s courage and eloquence as she stood on the podium in front of over 50 guests (young and old), dressed in her long hijab, and narrated her ordeal in just a couple of minutes. While the other two girls who shared their stories shed tears as they spoke, Aziza did not cry. I then decided to get in touch with Aziza to hear more about her story.

When Aziza was seven years old, her father divorced her mother and sent her out of the home. Aziza and her siblings remained with their father and his other wife. Aziza became a slave in her father’s home and her stepmother denied her and her siblings the opportunity to continue attending school; none of the children in the house attended school, even the boys. Rather, each day, her stepmother would fry Akara (bean cake) and send Aziza out to hawk and Aziza was conscious of the fact that she was falling behind her former school peers. Her father, the breadwinner of the family, never said anything to stop her maltreatment.

A few years later, Aziza’s father passed away and she went to live with her mother. One day, while on an errand to make her mother’s monthly financial contributions known as “Adashe” (community savings group), Aziza met a man, Mallam Hussein, Hussein told her that he liked her at their first encounter. He looked in his fifties and Aziza was not interested because of his age. However, he followed her home and started visiting occasionally. (Apparently, it is not unusual for potential suitors in this area to follow a girl home). On his third visit, despite knowing that Aziza did not like him, Hussein went to her uncle to propose marriage. Because Hussein was a wealthy man with social influence in the community, Aziza’s family found his offer impossible to turn down. Short after Aziza was informed that she would be a bride. Though Aziza’s mother was not in support of the idea, she could not voice her objection. As a divorcee, she was no longer considered a part of the family. And even if Aziza’s father was alive to object, paternal uncles tend to have more power in marital decisions.

Aziza had no choice but to go with Hussein. It wasn’t until she arrived at his house, that she learned he already had three wives and children. She became his fourth (and preferred) wife. As Aziza narrates her story in the Hausa language, it is evident from the look on my translator’s face that her story is tragic, filled with heart-breaking incidences of abuse. As for Aziza, she looked at ease; like someone who has accepted the fate she has been handed. I believe that my previous interactions, along with the fact that Aziza has chosen to be an advocate for girls, helped her to feel confident to share her story. She was fully aware of the purpose of our conversation and the goal of my research.

She shares that her husband had no respect for women. All he wanted from her was sex and he “sidelined the other wives” (who were older and had children) and chose to only have sexual intercourse with Aziza, day and night, even when she was on her menstrual cycle. “I’m just like a machine to him,” she said. He relegated his other wives to cooking and cleaning while he used Aziza for sex. Aziza started experiencing bleeding. She went to the hospital and conducted several tests and scans, but no diagnosis was ever made. Her husband refused to go to the hospital with her saying that she was wasting his money. All of this happened within seven months of the marriage. Her husband concluded that if Aziza was fine health-wise, she should come back to the house, otherwise, she should go back to her family. She returned to her mother’s house because of her health concerns and her family paid for her medical bills.

Aziza never enjoyed marriage. She complained several times to her family about ill treatment from her husband, including times when there was not enough food at home. Her uncles told her that she had no choice but to stay. “In marriage, you have to be patient and endure,” they told her. Her family felt that if she left her husband her only option would be prostitution. “Here in the north, when it comes to marriage, your father’s relations, they have very strong say. It’s a family thing when it comes to a girl’s marriage in the north,” said the translator. Aziza eventually got tired of speaking out about her problems because no one seemed to want to help. It’s been about five years since Aziza left her husband’s house. Though, she has regained her health, she does not intend to return to Hussein. He has refused to release her from the marriage because he still wants her as his wife. Because Aziza is the one asking for the divorce, Hussein is demanding that her family pay him N1.5 million (approximately $3,300), being the cost of his contributions to her family to have her as his wife. Aziza’s poor mother and maternal family cannot meet that demand. Besides the money, as I am told by a community worker, Hussein’s pride and desire for young and beautiful Aziza influences his refusal. It’s as if he is saying, “how can she decide to leave me? If I can’t have her, no one will.”

When I asked Aziza about her knowledge and thoughts on child/early marriage, Aziza responds, “once a girl reaches ‘Balaga’ (puberty), she can get married. I don’t consider it early marriage because the girl has begun menstruating.” I probe further to know if she thinks a girl who starts menstruating at nine years should get married. She responds, “It is not ok.” Aziza explains that she had first-hand witnessed young girls die in childbirth and/or be returned to her family after pregnancy complications. She claims that a good age to get married is 19 or 20 because at that stage the girl is more matured; “she has developed very well. In the process of giving birth, there might not be much complications as when the girl is 12 or 13.” Aziza’s desire to help girls in her community has motivated her to follow through on her early dream of having a career in nursing or education.

All Aziza wants is to be done with Hussein and gain her life back. She notes that she did not take anything with her when she left her husband’s home, except the clothes she on her back. Aziza would like to remarry , but she cannot remarry until Hussein grants her a divorce. Unlike her sister who was able to get divorced and remarry with comparative ease, Aziza is not as fortunate. Aziza explained that her sister had to get a divorce because “she was possessed with a demon” which was not compatible with her husband. A local Mallam ordered her sister’s divorce after spiritual consultation.

So, what is needed to annul Aziza’s marriage to Mallam Hussein? Because Islam does not give marriage certificates and marriage is initiated based on consent from both parties/families, all Hussein needs to do is give a verbal release granting her request for divorce. “He is an arrogant man,” she says. Her family has called him several times, but he refuses to release her. “You know this people, if they live in the village and have small money, they assume they are on top of the world so they behave abnormal,” added the translator. According to Islam, divorce can be granted if the man oppresses his wife and as such fails to grant her rights which are very important in the religion. In Aziza’s case, many see her as justified in asking for a divorce because of the ongoing health issues sustained as a result of Hussein’s aggressive sexual excounters.

Aziza is currently a first-year university student at a in Zaria studying education. When I asked if she has a role model, she tells me about “Malama Gudiya,” a young mother and wife in her community. Aziza admires Gudiya because she is the person that everyone (especially non-community members) goes through before anything can be done in the community. “She is the only person that understands English; she reads and she writes,” says Aziza. “I would like to be like her because she is educated.” Aziza has never interacted with Gudiya or told her how much she admires her; her admiration has been from afar. I encouraged Aziza to make an effort to let Gudiya know how she has inspires others.

As I wrap up my time with Aziza – we have spoken for over an hour – I ask her about issues facing girls in her community. She responds that life in Dakashi is okay. Kids go to school, but many girls are unable to finish primary school (for some lucky ones, secondary school) before they are given away in marriage. “Girls want to go to school, but their parents don’t have money to send them to school.” When finances get hard for parents, they ask the girl to “wait” and stay at home while they gather resources to keep the boys in school. “When it comes to education,” Aziza says, “parents can be reluctant to send their daughters to school. But when it comes to marriage, they put some effort to get the money.” The belief is that education for boys is “the main thing.” The girl will end up in the house or in the kitchen. Parents believe that when they invest in a boy, they will get something in return at the end of the day. However, investing in a girl is seen as a waste of resources.

Child/early marriage is a form of discrimination towards girls. It exposes girls to violence, exploitation and abuse. The lack of alternatives leaves many girls, particularly those in rural communities, with the choice of marriage, albeit pre-mature. In the quest to end child marriage in Nigeria, it is critical to understand why the practice exists. When parents have jobs and skills to help them take care of their children and girls have opportunities to receive quality and unbiased education, we will eliminate this harmful practice.

“You have to see the way these girls get excited about their marriages,” said a community worker. “It is as if they are happy to be getting married. They see it as an achievement. Many of these girls live very difficult lives; they have to hawk for food and have many responsibilities placed on them even as children.” Still, many girls would rather not get married before they finish secondary school. “Islam does not permit a father to give his daughter in marriage without her consent. However, the problem is that many girls [when a potential husband comes to the house] stay quiet and their quietness is taking as consent,” said the community worker who works in Aziza’s community.

Aziza has recently become an intern with a local non-profit working to promote girls education in Zaria. In her community, she experiences serious stigma as a potential divorcee. “The girls don’t come to me,” she says. “Parents tell their daughters not to talk to me or associate with me because I am a divorced girl.” However, this is improving due to her involvement with the non-profit organization. Her status is changing; her peers and community members now view and speak to her with respect. For my last question, I asked Aziza what she would tell the Governor of her state if she had a chance to speak with him about helping girls in her community. She responds, “If they can help girls go back to school. Most of the girls are idle; moving from one house to another; not really pursuing or achieving anything for their lives. If they can help them to see the importance of going to school and give them the chance and opportunity to go to school, everything will go fine.”

[1] United Nations Population Fund. Child Marriage. http://www.unfpa.org/child-marriage

[2] United Nations Children’s Fund, Ending Child Marriage: Progress and prospects, UNICEF, New York, 2014. https://www.unicef.org/media/files/Child_Marriage_Report_7_17_LR..pdf.

[3] Girls Not Brides. Nigeria. http://www.girlsnotbrides.org/child-marriage/nigeria/

[4] http://www.girlsnotbrides.org/about-child-marriage/

[5] Names have been changed for the sake of confidentiality.