May 2, 2016

I am in a Masarati speeding toward the dinner party of an Iranian collector. A publicist invited me an hour ago. The motor hums, gently massaging my back, as the car cruises past strip malls and warehouses that could be on the outskirts of LA.

At the destination, strings of white light bulbs dangle between two rows of garage-like storefronts. This is Al-Serkal Avenue, modeled after Chelsea, where blue chip art galleries have taken over an industrial district. Tonight, the main drag is blocked off for Farad Bakhtiar’s banquet. At two pop-up bars, several barmen are overfilling glasses of imported chardonnay and Chivas. Beyond them are twenty-some tables covered in white, crowned by saran-wrapped mezze and centerpieces of modest white flowers—a wedding party without a bride or groom.

I wander through Space WH2, Block B2, Bakhtiar’s storehouse, which he shows once a year. Hundreds of paintings and a smattering of sculptures and video art from the Middle East and South Asia are filed away here, all numbered and labeled. The collection is opulent, and I wish there were a catalog to guide me along. Afterward, I sit at a table with artists from Paris, writers from London and New York, and a filmmaker from Vancouver. On the dance floor next to us, a singer in a white shirt, collar open, wails Farsi choruses into a microphone, his voice cracking and his hips shaking. Men in suits and women in cocktail dresses join in, mouthing the lyrics and jumping up and down.

The tenth anniversary of Art Dubai, the grandest art fair in the Middle East and Asia, is a twenty-minute drive away. In Madinat Jumierah Hotel, a Venetian-Arabian resort village, 94 galleries from 40 countries exhibit thousands of pieces for international buyers and the Gulf’s wealthy royal families. Under the shadow of the seven-star hotel Burj Al-Arab, I trade business cards with art consultants, buyers, critics, curators, and dealers.

Many tell me that Art Dubai is more focused on the art and the artist than other global fairs, that it more readily engages with politics than Frieze or Art Basil. From my perspective, Art Dubai has more in common with indoor skiing at the Mall of Arabia than the arts communities I have gotten to know in Algiers, Beirut, or Cairo. This is a commercial affair, where a patron’s card assures a free ride in a Masarati.

Still, I am thrilled to see the works of pioneering Arab mid-century modernists, dazzled by the breadth of the new practice emerging from the MENASA region (Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia, a broad coinage that appears in much of the fair’s literature), and placated by free espresso and wine. I attend stylish lectures at the Global Art Forum, visit art spaces in the sleepy, neighboring Emirate of Sharjah, and meet artists from across the Middle East. But upon returning to Cairo, I am left feeling empty, pondering what lay underneath the glitz.

***

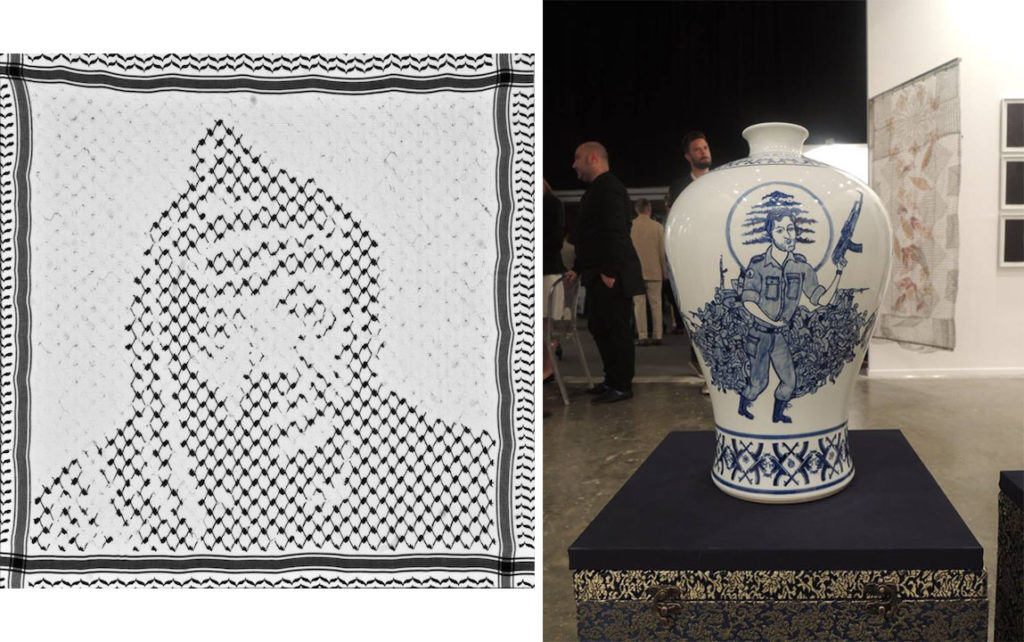

At Art Dubai, it’s difficult to let your eyes wander without stepping on someone’s toes. It takes at least three whirls through the massive exhibition halls before I finally see the art. I spot ceramic vases splattered with paint by Chinese dissident Ai Weiwei and an alabaster sculpture by Anish Kapoor who is famous for the giant silver bean in downtown Chicago, which he recently painted black. I pick up catalogs from Azerbaijan, Greece, Oman, Palestine, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. I drop by outposts of Al-Serkal Avenue’s many galleries. I snap photos of Lebanese civil war scenes adorned on traditional Chinese pottery, of Pac-Man moving through Kufic Arabic script, of Yasser Arafat composed out of a keffiyeh.

But for all of the political commentary embedded in these works, Dubai’s own political issues are avoided. Indeed, the fair is, “Held under the patronage of His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid al Maktoum, Vice-President and Prime Minister of the UAE, Ruler of Dubai.” Whether printed above the entryway or in brochures beside Art Dubai’s Bauhaus logo, these are important words.

In a monarchy, it might be said, art can challenge the status quo. But, throughout my time in the Gulf, I wonder if art simply distracts from the egregious acts occurring below the surface.

“The UAE is living in its darkest ages considering human rights in general,” says Ahmed Mansoor, an Emirati human rights advocate. He details authorities’ systematic use of torture with impunity, notably black sites where Emiratis and foreign nationals are held for long periods incommunicado. The State Department, UN rapporteur, and international NGOs have documented such offenses, and Mansoor suggests that many more cases of extralegal detention and corrupt practices go undocumented. Victims are rightly afraid to speak out, largely because there is no separation of powers; State Security targets whistleblowers and urges the courts to pursue harsh sentencing.

Mansoor himself is one of the victims. In 2011, he was arrested on trumped up charges related to an open online forum he had founded called UAE Dialogue. He was convicted of “publicly insulting” UAE leaders. He served eight months in jail, until the president pardoned him. Due to his criminal record, however, he lost his job. Upon returning to his studies, he was assaulted twice and received many threats, pressures that forced him to drop out of law school. Among the other forms of harassment he has faced: $140,000 disappeared from his bank account, his car was stolen, his communications hacked. Authorities confiscated his passport in 2011, which means he is unable to leave the country.

I asked Mansoor what he would say to Art Dubai attendees. “I would urge these people not to ignore the human rights,” says Mansoor. “It’s a core subject in arts in general, and they should not overlook it for the opportunity to participate in any festivals.”

* * *

Sitting under white umbrellas and palm trees, beside an artificial canal and espresso in hand, I consider Mansoor’s grievances.

In spite of the lack of freedom in the country, it is difficult to not also consider the positive aspects of Art Dubai. For instance, the fair seeks to democratize the global arts market, tipping the scales away from Europe and North America and towards the Middle East and Asia. One way in which Art Dubai counters Western hegemony in the arts is by showing pioneers who are under-appreciated in the Western context. A separate hall dedicated to works from the mid-twentieth century, Art Dubai Modern, is where the region’s forgotten masters are being revived.

The Dubai-based Meem Gallery exhibits two Iraqi artists: Faiq Hassan (1914-1991) and Shaker Hassan Al-Said (1925-2004). Hassan’s colorful portraits veer between cubism and expressionism. In the oil “Bedouin Tent” (1950), two men share a pot of Arabic coffee. Hassan’s brush melds abstract techniques with traditional milieus, suggesting that modernism is not a Western idea or import, but an expression of how people grapple with the self and the other in the face of technological, social, economic and political change. Hassan studied in Paris and was no doubt influenced by Picasso and friends, but the scenes captured by the Iraqi pioneer’s brush are at once Iraqi and Arab, and universally human. And Hassan’s figurative oeuvre neatly contrasts the messy mixed media mélanges of Al-Said, another Iraqi great, who was splashing paint on canvases at the same time as Jackson Pollack.

Beside Meem’s stall is Shirin Gallery’s, featuring the works of Iranian cartoonist and painter Ali Akbar Sadeghi, a self-proclaimed surrealist and expert animator. Late one afternoon I am lucky enough to meet Sadeghi. A language barrier means that we don’t talk too much. But his animations speak for themselves (note to self: learn Farsi).

In “The Rook” (1974) a simple chess match serves as an allegory for transnational squabbles. The game pieces—characters that blend classic Iranian miniatures with Peter Max psychedelia—move unconventionally, pawns piling up and elephant-bishops wobbling diagonally across the board. Stunning and whimsical, I watch it again and again. Likewise, “Flower Storm” (1972) depicts how quickly and capriciously leaders launch battles. In this short, as two kingdoms go to war, the children teach the adults a lesson by replacing the infantry’s cannonballs with flowers and birds. This act of defiance implodes the war and erases the fault lines between the two warring factions. At 79, Sadeghi continues to work ten hours a day. In fact, he seemed a little bored hobnobbing with potential customers at the art fair. Says Sadeghi: “Tomorrow morning, I have to sit and paint.”

* * *

Iranian and Iraqi art beside one another might seem like a small feat, but at a time of sharp conflict across the Gulf, Dubai’s art sphere has allowed Arabs and Iranians to develop relationships. That’s what Sultan Sooud Al-Qassemi wrote in a recent column for CNN. Al-Qassemi, who hails from Sharjah’s royal family, established the Barjeel Art Foundation in 2010 to promote modern and contemporary Arab art through exhibitions and education initiatives. (He tells me that he purchased Hassan’s “Bedouin Tent,” and news reports say the price tag was $250,000.) Al-Qassemi’s frenetic personality thrives on social media, where he often calls for significant policy reforms and shares critical articles about the Emirates. “I am in the minority, and I know this,” he tells me. “And that’s why I am willing to push and be patient, push and wait, push and wait.”

When I visit Barjeel’s two floors of smartly curated contemporary art as part of an Art Dubai press trip, Al-Qassemi is in Jordan for the Global Commission on Internet Governance (he advocates for open and free Internet access as a human right). We catch up on Skype a few weeks later, and I express my qualms about the Emirates, among them: an American charged with a misdemeanor for defaming the country under its vaguely worded 2012 Cybercrime Decree; a Jordanian journalist who disappeared in February and is thought to be imprisoned, incommunicado; the ongoing harassment of Ahmed Mansoor. “There’s ten million people living here, and the fact that you still identify these cases by name means that they are extremely in the exception,” says Al-Qassemi, adding, “There shouldn’t be a single one of those cases.”

Arts gatherings are important spaces for dialogue, he argues, especially “as the other spaces disappeared, this became the only refuge.” At cultural forums across the Gulf, there are conversations about women’s rights, immigrant rights, social issues, and gender issues absent from other arenas: “You might be surprised to hear this: the boldest debates in the UAE take place under an arts umbrella.”

Al-Qassemi mentions Art Dubai’s Global Art Forum, which he calls accessible, edgy and free (in contrast to an arts conference we both attended a week earlier in Doha, where entry cost US$1,995). On the Madinat Jumierah Hotel campus, past two white-table-clothed bars, a manicured patch of grass, and across a wooden footbridge is a white tent where the Global Art Forum is convened, bringing together an elite clique of Middle East and European art practitioners.

The theme of this year’s Global Art Forum is the “The Future Was.” Over three days, 23 presentation or panels fill in the blank: The Future was the Past, The Future was Space, The Future was Dubai, The Future was Smart, The Future was Dichroic, etc. Many of these one-liners are printed on pins that participants clip onto their Art Dubai tote bags. But by focusing on an imagined future and eschewing the nostalgia inadvertently tied to anniversaries, conversations about the present are lacking.

Facing a hundred or more attendees, forum commissioner Shuman Basar sits on a black leather couch with lava lamps on its sides. “Does the future still feel like it could happen?” he asks in his opening remarks. Behind him, a slideshow plays of decade-old advertisements of Dubai as a space-age site for construction, economic growth, and prosperity, imaginations of how Dubai was meant to look in 2016 and beyond. “I have always described [Dubai] as the making of a utopia without any of the pesky political obligations that utopia usually has,” Basar says.

After the conference, I ask Basar what it’s like to host a public forum in an undemocratic context. “We don’t feel hindered by these red lines when we’re planning but I think we probably work around them unconsciously,” he tells me. When I push him on this point, he says, “there’s no such thing as pure freedom of speech anywhere.” But Basar avoids the essence of my query. I am less concerned about the censorship of nude portraits in the art fair (ridiculous, yes, but not surprising), and more concerned about whether deference for the ruling family or avoidance of rights violations occurring in the country influences conversations at the forum. I wonder whether those at Art Dubai are unaware or willfully ignorant of ongoing atrocities.

One such issue whose absence weighed heavy at the Global Art Forum is labor. In the framework of dialogue about technology and futurism, I would think that labor is a sensible topic to address. After all, this futuristic city has been built by thousands of low-wage workers, and their mistreatment is well documented. “We haven’t found either an occasion or a specific format in which we would be able to do something that hasn’t been said or done already,” Basar says. “When you go to Frieze, why are there no conversations about the making of the construction politics of Tate Modern 2, or discussions in Art Basil Hong Kong? Why is this topic limited to the Gulf?”

The reason is perhaps because among the Emirates’ 10 million residents, about 90 percent are foreign workers. A group of artists and academics known as the Gulf Labor Artist Coalition has drawn attention to the need for significant reforms. They’ve focused on Saadiyat Island in Abu Dhabi, where the Guggenheim and the Louvre are building satellite museums. After six years of coordination, the Guggenheim Board of Trustees cut off communication with Gulf Labor on April 16, having “reached the conclusion that these direct discussions are no longer productive.” Gulf Labor has responded by projecting phrases like “Ultra Luxury Art, Ultra Low Wages” on the Guggenheim’s New York building.

Imagine if an artist from Gulf Labor had been invited to present at the Global Art Forum (The Future Was Undocumented Labor?), and a panel of business leaders and government officials had then been engaged in conversation (The Future Was Neoliberalism?). “Labor conditions should be a universal concern, and I wonder why they’re only picked out when it comes to projects in the Gulf,” Basar tells me. That too sounds like a compelling topic for a panel.

* * *

My briefcase is filled with free magazines, handed out by booths advertising Art Forum and Art Newspaper as well as a potpourri of Gulf-based art periodicals—none of which are published in Arabic. Hassan Khan, an artist, writer and musician from Cairo, is trying to change that. He wants to cultivate new arts criticism in Arabic. This year, Khan headed up the Forum Fellows programming, and with Art Dubai’s support invited four writers to participate in workshops. One of those writers, Ahmed Naji, is in prison, and I have been following his case closely (See JG-8 and JG-9 for details).

On Art Dubai’s website there is an asterisk next to Ahmed Naji’s name, and below it reads:

*Ahmed Naji was unfortunately unable to attend the fellowship workshops due to his sentencing by an Egyptian court for ‘violating public decency’ when a chapter of his published novel The Guide for Using Life appeared in an official literary weekly in Cairo. Naji is currently in prison. He is serving the maximum two year sentence he was given by a higher court after the prosecution appealed the decision of a lower court to acquit him of all charges. The vast majority of the Egyptian intelligentisa (including several previous as well as the current Minister of Culture) have expressed public solidarity against what is perceived as a rare and unfortunate assault on literary expression. At this pivotal moment the collective efforts of writers, artists and thinkers is essential in helping to formulate what comes next. A process of legal appeal is underway and we can only hope that Naji’s ordeal will end soon.

It took a lot of pressure to add this blurb to the Art Dubai website.

Shumon Basar tells me that Art Dubai acted in solidarity with Naji. But the only form that the solidarity took was that footnote on a website. I contact Art Dubai’s communications manager, and she replies, “it was decided that as a mark of respect and solidarity his name should continue to be included in all materials and to publish the statement online.” On March 14, Ahmed Naji had already been in prison for three weeks. Art Dubai tweets to its 75,000 followers about its Forum Fellows, including Ahmed Naji, without mentioning that he is in prison.

***

Three weeks later, a white taxi ferries me through Tahrir Square and towards a small Cairo apartment, home to the local art collective known as the Nile Sunset Annex. They are exhibiting seven objects that had been Art Dubai commissioned and shown at the fair. With a price tag of $75, each object is a rebellion against the emirate’s commercialization of art.

I am still grappling with the contradictions of Art Dubai. The fair’s tote bag is swung across my shoulder, and I outline my newsletter in a branded Moleskine notebook—both were in the welcome package waiting in my Dubai hotel room. As a writer, I think that producing straight-up art criticism about the works I saw at the fair is insufficient. (Though one Emirates-based academic told me to be careful even when writing art in the Gulf, as you might criticize the wrong person, perhaps the relative of a royal bigwig.) Yet I am glad that I attended so that I can better comprehend the dissonance between Dubai’s advertised achievements and not-so-hidden shortcomings, something that I tried to elucidate in this newsletter.

Each individual decides whether participating in Art Dubai is a compromise or an opportunity. But when arts practice is sponsored by a state apparatus—one that is perpetuating grievous abuses of power—the artist has a responsibility to ask questions. Should the artist communicate through his or her art, or through other forms of action? Should the artist boycott such events? These are the same questions that I was asking of myself.

At Art Dubai, this topic is addressed by “Plot,” an installation by the New York-based artist Sreshta Rit Premnath. It is six bunk beds, broken and slanted yet sharing a single frame, evoking the small spaces occupied by the workers who have constructed the kingdom in the sand. “Plot,” which was commissioned by Art Dubai itself, sits in the center of it all. It is not far from a flashy stand of The Cultural Office of Her Highness Sheikha Manal Bint Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum and smaller outposts of official and semi-official entities like the National Pavilion of the UAE, Qatar Museums, and Sharjah Art Foundation. Premnath’s installation is at once a subversive act and a concession that to make art in the world today means a reliance on unsavory patrons. The abuse of laborers is simply part of the art ecosystem here. When I first glance at Premnath’s work in the foyer of Art Dubai—between a bookshop, information stands, and an espresso bar—I think it is furniture.

Top photo: Art Dubai 2015 Contemporary Gallery, courtesy of Art Dubai.