YILAN, Taiwan — Although other villagers refer to her as Yaba Ayi, or “mute auntie,” Aunt Ah-suan does not lack for expression. When the Land Dyke member and rice farmer Yen-ling offers her a pomelo, she throws up her arms, sun-toned from decades of laboring and collecting recyclables on the open alluvial plains, and lets out a high-pitched squeal with hints of Taiwanese Hokkien: “You eat first!” Underneath her conical straw hat, fortified with red-and-white-striped woven burlap, she squints through an open-mouthed smile, one upper molar protruding from each side of her mouth.

Amid the back-and-forth over who should eat the pomelo, Aunt Ah-suan taps my shoulder. She directs my gaze to a pile of bricks beside a bamboo grove that shelters her home, tracing imagined bamboo shoots from the ground up before furiously sweeping her hands over the plot of scattered brick and dry grass. “This big—the bamboo grove used to be this big, this tall,” she seems to suggest, repeating the movements indicating height and expanse.

Then, abruptly, a melodic groan discharges from deep within her chest. Wrinkles deepen across her face like cracks in dry mud, and the imagined grove collapses in our minds.

I learned from Yen-ling, a rice farmer who has tilled the land next to Aunt Ah-suan’s home for over 10 years, that what remains of the bamboo grove—a thick cluster of shoots and branches protruding over the adjoining roads—occupies less than half of its original area. At its peak, more than 50 family members lived with Aunt Ah-suan in the earthen homes hidden within, alternately plowing the rice paddies spliced and irrigated by rivers around them. But since the late 1990s, as family members followed a wave of rural-to-urban migration in search of more lucrative and sustainable work, she has lived alone. By the end of 2023, Aunt Ah-suan’s family decided to sell the entire grove to developers.

“The only reason the entire bamboo grove isn’t razed yet is because of Aunt Ah-suan,” Yen-ling said. Even as a construction company arrived to level the ground earlier this year, Aunt Ah-suan refused to leave, her body and bed the final fortifications against the developers and a new luxury farmhouse.

As Yen-ling explained the situation, Aunt Ah-suan interjected with strained groans and scrunched glares, piercingly searching for validation. Eyeing the patch of bricks and the garishly sterile farmhouses jutting above the landscape, her brows furrowed as she shook her head and hands in frantic disapproval.

“Her future is unknown to us,” Yen-ling told me as we walked away after our break under Aunt Ah-suan’s bamboo grove to return to the rice paddies. “Her family says they will build a new home for her once the developers sweep away the rest of the grove. But no one is asking her why she has decided to stay in place. To us, she is our dear neighbor.”

For the Land Dyke farmers, Aunt Ah-suan’s bamboo grove is not only one of their few sources of shade in the Lanyang Plains but also a symbol of the social, economic and political forces that influence their livelihoods as a small collective of women farmers in Tshim-Kau Village. “Not only as LGBTQ+ people but as small farmers in Taiwan, we are always existing in an unstable space,” Yen-ling said. “Our situations may be without hope to start but we are trying to articulate an alternative to these norms.”

I visited Land Dyke to learn how a gender-inclusive farm collective, now over a decade since its founding, has continued to “use the land to welcome people”—a direct translation of the farm’s Mandarin name—particularly invisible minorities in Taiwan’s countryside like women and queer people. However, traditional farmers themselves are being displaced, no longer as welcomed or valued in an economy where land is increasingly scarce in the face of land speculation and development.

There’s something precious, then, in the Land Dyke women’s choice to quietly plant a stake in the ground—to still welcome neighbors like Aunt Ah-suan and me and rewrite how to cooperate in an economic system that is splicing and bulldozing the land.

* * *

In 2019, former Agriculture Minister Chen Chi-chung publicly admitted that “Taiwan’s farmland is now the world’s most expensive. This is indisputable.” At that time, the average price of Taiwanese farmland had reached 48 million New Taiwan Dollars (NTD) per hectare, about $1.5 million, which cost 157 times more than agricultural land in the United States the same year. Based on analyses of transaction records during the 2010s, farmland prices across the island increased exponentially, as much as 117 percent in New Taipei City between 2010 and 2018.

Scholars trace the trigger for the trend to 2000, when the Agriculture Ministry amended the country’s Agricultural Development Act (ADA) in a last-ditch attempt to win votes for the ruling Kuomintang (or Chinese Nationalist Party) ahead of a general election. Overnight, the landholding system in Taiwan shifted from a “farmland owned by farmers” (nongdi nongyou) policy to “farmland for farm use” (nongdi nongyong), allowing non-farmers to buy farmland provided that they keep it for agricultural use. However, the enforcement and definition of “agricultural use” was loose and often unregulated, leaving a loophole that encouraged land speculation.

In 2006, the completion of the Hsuehshan Tunnel cut the journey from Taipei to Yilan County to half an hour from the previous two hours. Very soon, “farmhouses” began to emerge at exponential rates across the county’s agricultural land. Comparing data from the Interior Ministry’s Building and Construction Administration—which approves licenses to construct farmhouses—with violations noted by Yilan’s agricultural committee, it appears that at least 60 percent of the farmhouses were used for anything but agricultural use, including as second homes for Taipei residents, bed and breakfast hotels, restaurants and factories. Controversially, to circumvent the “farm use” regulation, non-farmer developers often made informal agreements with farmers to build outside the law’s purview—and then quickly transfer ownership. In 2015, the Yilan taxation bureau discovered that 60 percent of farmhouses built at that point had transferred ownership within three years of construction, in contravention of the five-year minimum stipulated by law.

Former Agriculture Minister Peng Tso-kwei, who resigned after refusing to amend the ADA in 2000, pointed out that agricultural land is being lost across the island at a rate of more than 3000 hectares every year. In Yilan alone, official statistics from the Interior Ministry’s construction administration note that more than 10,000 farmhouse licenses were issued between 2000 and 2022, and the number of farmhouses continued to rise even as the number of rural households decreased. Some estimate that the real number is likely much higher, with local governments lacking the capacity or incentive to inspect, and passively allowing the situation to worsen.

“Since 2016, the county government has been staunchly pro-development,” Yen-ling said during a car ride to the rice processing plant. I’m told that in addition to the emergence of three-story farmhouses that break up the patchwork of rice paddies and bamboo groves, construction sites and “For Sale” signs have become regular features of the landscape, irreversibly damaging Yilan’s biodiversity and national resources. Concrete pillars pollute groundwater and irrigation channels with heavy metals and other waste for years after a building’s construction and scatter the natural fauna for kilometers beyond a building’s foundation. Environmental groups including the Yilan Irrigation Association have long called attention to nitrogen and phosphorus from human waste, food and soaps polluting waterways and compromising crop quality. Another unintended yet dangerous consequence of farmland development is the risk of flooding as surfaces such as asphalt and concrete seal the soil’s surface, reducing rainwater absorption.

A strong coalition of real estate developers and landowning farmers have supported such construction over the years. I wanted to know why farmers would also be in favor of the new luxury farmhouses.

Over 80 percent of Taiwan’s agricultural sector is comprised of small-scale family farms, each owning at most one hectare of land. It was the result of land redistribution efforts in the 1950s that sought to reverse a fiefdom system under Japanese occupation. However, farmers operating small farms can’t achieve economies of scale or easily adopt new technologies, limiting profits. Moreover, due to the nature of Yilan’s natural conditions—a lot of rainfall and minimal sun year-round—most farmers only have one, at most two, planting seasons. In an interview with the Taiwanese data journalism platform READR, an old farmer named Ye Tshing-wen lamented that one hectare of rice may yield only 200,000 NTD in profit per year.

As Taiwan’s industrial growth spurred greater productivity in cities and higher incomes, most families began to see their futures away from the rice paddies and fruit orchards. By 1980, most Taiwanese farming families were already receiving 70.4 percent of their income from non-farm activities. “Land has lost the sacred character it used to have,” the agricultural economist Huang Chun-chieh wrote of farmers’ attitudes in the 1980s, as they pursued joint management and other strategies to combine land and prioritize profit.

Land Dyke utilizes organic farming methods to preserve the natural fauna and water channels around their paddies

The statistics were further exacerbated in 2002 when Taiwan joined the World Trade Organization and now had to adhere to rules eliminating bans and lowering tariffs on foreign goods. The global trade body added new elements of international competition. That year, the country’s domestic agriculture suffered losses of 6.5 billion NTD ($1.56 billion), largely due to the inability of Taiwan’s small farms to compete on an international stage. Agriculture now comprises less than 2 percent of Taiwan’s total gross domestic product (GDP). The promises of an export-driven economy have yet to arrive in Taiwan’s countryside; instead, rural communities are left with empty luxury farmhouses, utilized for a few weeks a year (if at all) as vacation homes.

One reason for farmers’ regard for selling land as a pragmatic way forward is the dwindling tradition of passing down one’s farm to one’s heirs.

By 2015, farmers under the age of 45 represented less than 6 percent of the country’s total number, compared to 46 percent for those over the age of 65, according to the Digital Museum of Rural Taiwan. While most farmers say they would support their children if they chose to take over the land, some 70 percent said they would not directly or actively arrange it. Aunt Ah-suan’s family is unexceptional in that regard; their bamboo groves and fields hold neither productive use nor sentimental value to anyone beyond Aunt Ah-suan.

“For many landlords, farming is a hopeless occupation, both in the present and future,” Yen-ling said.

The government has tried to selectively intervene in this scenario, mostly in the name of its food self-sufficiency rate—a measure of how much of a country’s food consumption is produced domestically. Taiwan’s rate currently hovers just above 30 percent, which would place the island nation at high risk of starvation in the event of a naval blockade—a likely low-cost, low-risk scenario of Chinese aggression. Indeed, Taiwan is currently heavily dependent not just on food imports but also deliveries of agricultural inputs, such as livestock feed, fertilizer and raw materials. The government has encouraged farmers to switch from rice to in-demand staples such as soy, peanuts, sweet potatoes, corn and Chinese pearl barley.

In order to address the aging of the agricultural population, the government has increasingly subsidized training programs and initial startup loans for urban-to-rural migrants while also increasing investments in vertical farming and other forms of agricultural technology.

But due to a lack of government regulation of non-agricultural land use, many new small farmers have no pathway to owning land. Farmland is often sacrificed for others’ economic realities or even geopolitical concerns. The environmental advocate Chia-shen Tsai of Citizen of the Earth’s Taiwan chapter reported that some farmers have also started to lease their land to solar energy firms as a profitable investment in light of Taiwan’s campaign for energy security.

Another problem for most small farmers is that they don’t have official leases with their landlords. Because Taiwan legally defines a farmer based on farmland ownership, in the absence of such paperwork, farmers such as those in Land Dyke (who neither own land nor lease it under written contract) are invisible in the eyes of the state. When I asked Yen-ling and Kai-lun if they had access to government subsidies for climate change or other governmental support, the answer was a weary “No.”

To be a small farmer is to diligently return to the field, year after year, even as the agricultural sector loses favor in the face of developers and real estate moguls.

In 2016, former county magistrate Lin Tsung-hsien attempted to levy a land value tax as a way to curb the development of “farmhouses” and the rampant land speculation in Yilan, which at that point had the highest concentration of farmhouse construction and licensing in the country. He immediately faced backlash. Coalitions of real estate developers and farmers’ committees took the issue to the central government and Lin resigned from his position, confirming that to oppose development is to face political death.

Land Dyke’s former member Wu Shao-wen also lost to pro-development candidates in her own electoral race to represent Yilan in Taiwan’s parliament that same year. While grassroots movements have persisted—such as the citizens’ watch group Protect Yilan Workshop and the distributive land trust and farmers’ education center Island Time—Yen-ling said that the new farmers’ movement has quieted down a lot since then.

As we chatted, Yen-ling seemed to indicate she had come to terms with the futility of her chosen path. While not yet defeated, she is not optimistic about a solution. Indeed, there is no guarantee that the land beneath Yen-ling and Kai-lun’s rice paddies will be there next year. At the end of a recently-released Taiwanese documentary called “Soul of the Soil” (Zhong Tu, directed by Yen Lan-chuan), the construction of the high-tech, industrial Ciaotou Science Park in Taiwan’s southern city Kaohsiung catalyzes the sunset of many farmers’ agricultural careers. The children of an organic farmer named An-ho, one of the documentary’s primary subjects, leave their family farm on facing the risk of displacement. At the beginning of the documentary, a values-driven and jovial composter called Ah-jen aspires to take Taiwan’s soil “out of the intensive care unit,” ravaged by chemical fertilizer. But even he falls into despondency when faced with economic pressures and the realities of Taiwan’s trash, eventually returning to a job in the high-tech industry.

There are layers to the crisis that folks like Yen-ling, Kai-lun and An-ho face: environmental destruction, the lack of recognition for organic farming, economic and geopolitical pressures and developmental displacement, among others. Rural advocacy groups across Taiwan have proposed a range of solutions from legislative reform that would protect and directly subsidize agricultural land to the creation of a nationwide land trust akin to the United Kingdom’s National Trust, or simply stricter enforcement of farmhouse regulations.

Within these crises, Land Dyke imagines a different way to farm beyond the existing “family farm” model, in which land, knowledge and resources are doomed to be lost as younger family members migrate to cities. Rather than kinship, Land Dyke relies on pooling resources and creating connections with other local villagers—their contractors and processors are all local—as well as with their consumers. Land Dyke’s customers often pay for produce in advance to help subsidize the farm’s needs during the harvest season. While that does not provide a solution to the overarching market and developmental pressures, it has prolonged Land Dyke’s longevity in the paddies as many other farmers continue to walk away, head bowed down, dirt-stained pants tossed in with rusted shears.

* * *

Aunt Ah-suan beckons me to the shaded bench where she is seated, just adjacent to Land Dyke’s fields. After scything through the last rice stalk in my assigned corner of the paddies, I wave back and start wading through the half-flattened rows of crop stubble between us. The rice harvester’s engine continues to groan in the background, the machine moving around the field in concentric squares.

As I approach her, Aunt Ah-suan repeatedly pats the bench space right next to her. When I finally sit down and take off my sun hat, she points out some of the acne on my forehead and, amid utterances, punches me gently on my arm.

“I think she’s saying that you are handsome even with the acne,” Kai-lun—another Land Dyke member and fellow rice farmer, dressed in neutral tones—says as she and Yen-ling join us. We all laugh as I thank Aunt Ah-suan for the compliment in my minimal Taiwanese Hokkien.

As the Land Dyke farmers and I silently take in the landscape during our break, Aunt Ah-suan begins to point toward some of the farmhouses in the east. We believe she is sharing more history of the farmlands around us—the passage of land rights, the migration of families—and Yen-ling interjects intermittently to confirm if the history she has gleaned from their neighbors aligns with Aunt Ah-suan’s memory. At one point, Aunt Ah-suan uses her right pointer to outline a portion of a Chinese character on the palm of her left hand:卩. After a few guesses, we deduce the name of one of her landowning relatives.

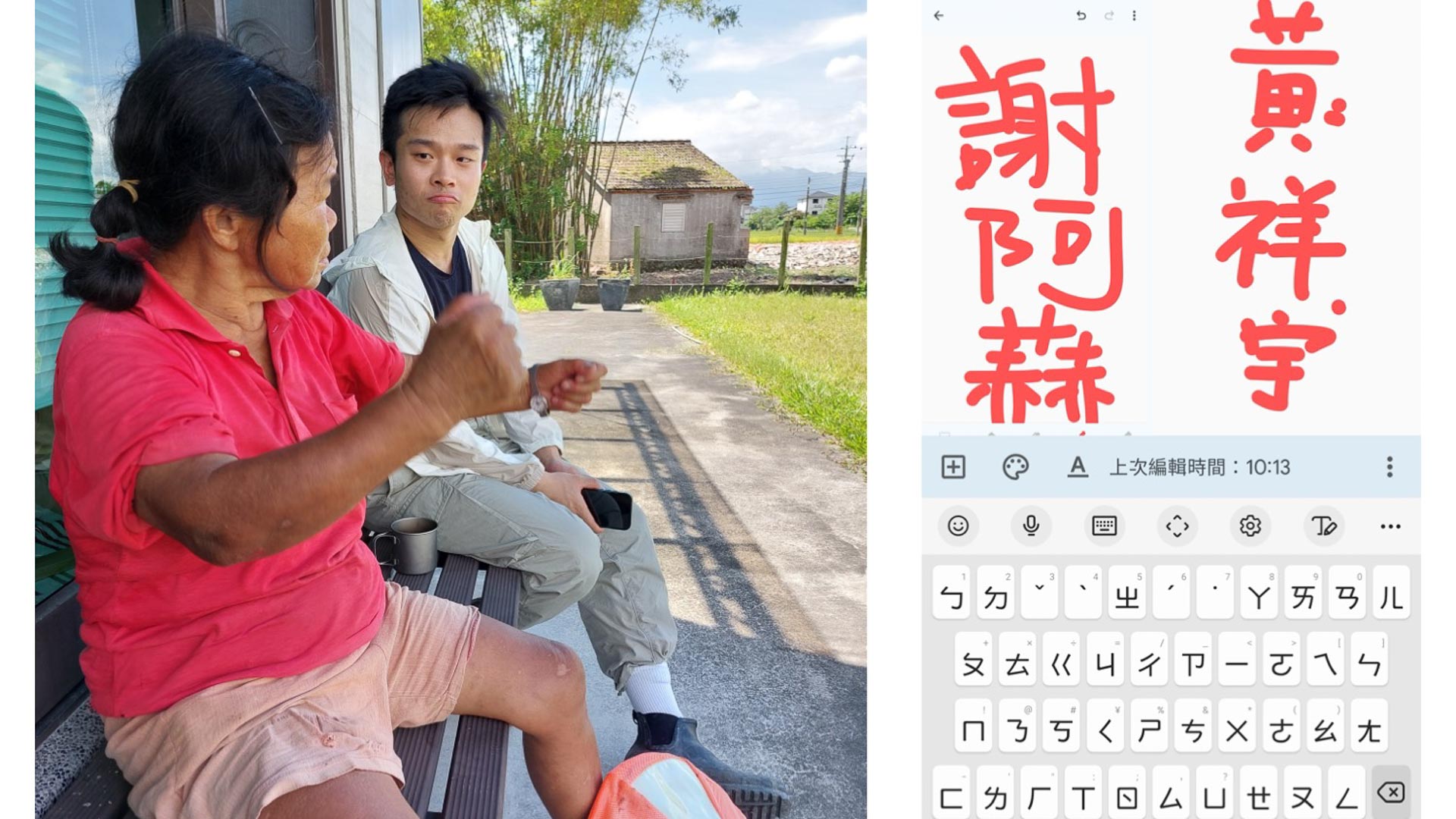

“We had no idea that Aunt Ah-suan can read and write!” Yen-ling exclaims. She opens a note-taking app on her smartphone and we take turns writing our Chinese names for Aunt Ah-suan. Each time, she squints at the screen for a few seconds, her finger passing over each character, and once she reaches the end, she points at the respective person and laughs in recognition. Her tightly wound ponytail bobs behind her with each wide-mouthed chortle.

I think back to the agricultural economist’s observation of Taiwan’s shifting farmlands in the 1980s: “Land has lost the sacred character it used to have.” Today, land is most often viewed as an input for generational wealth, national security, technological innovation. For these women and queer folks, whose knees ache from weeding and picking invasive snails off rice paddies, the lands are not sacred either. But here, in this collage of bamboo groves and rice paddies and orchards, they are experimenting, gradually finding new ways to survive, and finding refuge in each other’s laughter.

Top photo: Kai-lun and Yen-ling spread green manure over their rice paddies after the harvest