RIGA, Latvia — Elena Trifonova brought with her only one bag packed with summer clothes when she left Russia for what could be the remainder of her life. The 47-year-old Irkutsk-born journalist had been planning to visit the Georgian capital, Tbilisi, for just two weeks, for a media-management workshop, in September 2022. Boarding her flight, she had no idea she would be leaving behind her husband and 18-year-old daughter indefinitely.

That day, security service officers in Irkutsk raided the office of her online magazine Liudi Baikala, or People of Baikal. Upon arriving in Tbilisi, the journalist—Elena Trifonova is her pen name—said she and her colleagues realized their options were to either “return and go to prison or remain abroad where [they] could continue their work.”

Without enough money to rent an apartment in a city where newly arrived Russian draft-dodgers were inflating the housing market, they found a cheaper place in the nearby Armenian capital Yerevan. Trifonova stayed there two weeks before a Latvian organization named Media Hub—which helps international journalists at risk seek refuge in Riga—contacted her with an invitation to the Baltic capital.

Several hundred Russian journalists were already there, most working for US-funded Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL), the BBC’s Russian Service or popular independent Russian media such as the Meduza website and Dozhd TV.

Shortly after Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, their employers had rented evacuation buses that the fleeing journalists packed with belongings to last several years. Many even brought their pets.

At the time, Trifonova had felt compelled to remain in Russia to report on “how the wheel of history was actively turning” in her country, she told me in the kitchen of Media Hub’s office in Riga, with long highlighted bangs hanging over her right eye.

The war had changed her beat, she said; instead of reporting on “how the state was draining people’s resources,” she was now covering how Russia’s rural population is “paying the state with its lives.”

It’s a major topic into which few Russian journalists, especially those living abroad, have insight.

The war is devastating society and economies in the country’s far-flung regions, where extremely low salaries continue to compel men to join the army voluntarily, and mobilized conscripts lack resources to dodge the call-up. As a native of her Siberian region, Trifonova possesses local contacts that enable her to continue covering Irkutsk in ways few journalists from Russia’s biggest cities could.

Trifonova and her colleagues were the first to report on burials of Russian soldiers the authorities had kept hidden. But coming from Siberia also means she lacks the connections that support many of her peers. People of Baikal was a bare-bones operation funded by grants and donations, so money was always scarce. She was unaware of Western organizations that could have helped her find safe passage to Europe.

“I had never been to Europe before,” she told me. Irkutsk, near the world’s largest and deepest freshwater lake, Baikal, is almost 4,000 miles away. Moscow and St. Petersburg, by comparison, are each just under 600 miles from Riga.

Even in exile, Trifonova’s work remains important to her audience, which has grown since the start of Russia’s invasion. Before the war, People of Baikal circulated primarily among local readers, but since the invasion, major independent Russian media outlets cite its reports almost daily.

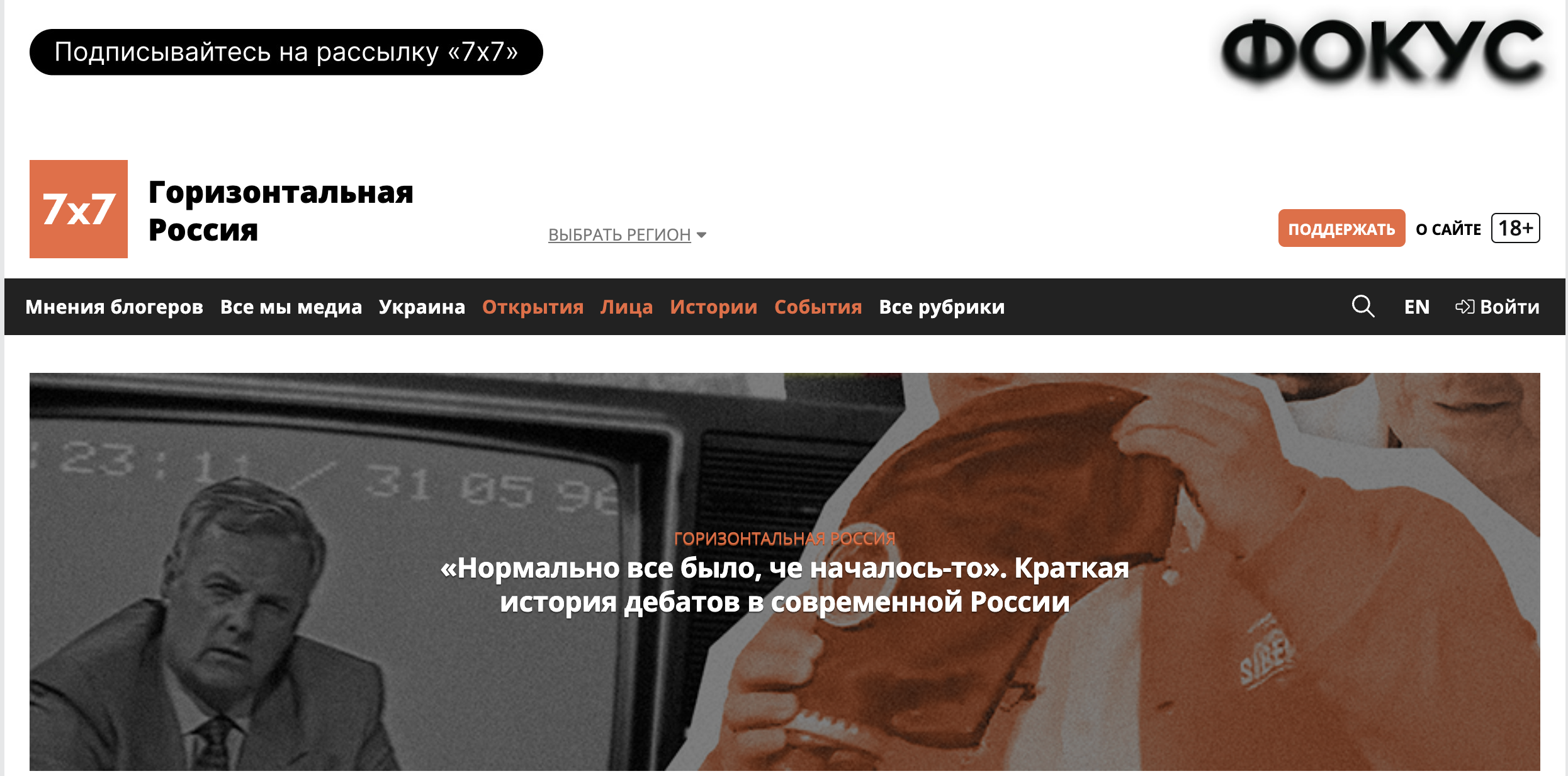

The war has spiked demand for regional news, says Oleg Grigorenko, another exiled journalist who runs the digital publication 7×7 Gorizontalnaia Rossiia (7×7 Horizontal Russia), founded in Russia’s northern Komi Republic and now based in the Lithuanian capital, Vilnius.

“Now in emigration, I’m seeing a ferocious interest in the regions,” he told me at a café in Vilnius’s old town. “Our expertise is very much in demand by larger independent outlets.”

Both People of Baikal and 7×7 Horizontal Russia rely on tight-knit network of anonymous correspondents and volunteers inside Russia and occasional leaks from local officials to continue reporting on the country’s remote corners that are off the radar of major independent Russian outlets.

And both Grigorenko and Trifonova say the invasion of Ukraine has raised questions among residents of and exiles from Russia’s western urban centers about how the war is affecting the rest of the country and why so many people from rural areas apparently support it.

Regional journalism before the war

The Kremlin has steadily has tightened its control over Russian media since Vladimir Putin assumed power in the year 2000. Just a year into his presidency, the state forced full control over the flagship channel NTV, transforming the leading independent television network that aired political satire into a blatant propaganda channel.

The murder of journalists such as Anna Politkovskaya—who rose to prominence for her coverage of the second Chechen War and was shot outside of her Moscow apartment—has been another hallmark of Putin’s rule.

In the years leading up to and following Putin’s 2012 re-election to a third term, repression of the free press ramped up. Major holding companies owned by Russian oligarchs swallowed up non-state news outlets such as Lenta.ru, Gazeta.ru, RBC and the Kommersant newspaper.

That prompted the creation of robust independent media outlets like Moscow’s TV Dozhd (Rain), and the Riga-based news outlet Meduza, which—thanks to paid subscriptions, Western grants and advertising—had the resources to employ journalists defecting from other publications.

Simultanoeusly, Western-backed surrogate media like the BBC’s Russian Service and RFE/RL, were also opening up more vacancies for independent journalists.

“Before the anti-Putin protests of 2011-2012, there was still some life in [the Russian independent] media landscape,” Ilya Barabanov, now a special correspondent at BBC’s Russian service, told me, smoking a cigarette at an outdoor café in Riga. “But once censorship grew and commercial contracts were interrupted, it became much more attractive to work for Western corporations.”

The ever-worsening environment was especially difficult for honest journalists based in the country’s regions, where resources were already scarcer than in Moscow. Many regional newspapers were compelled to rely on government grants or subsidies for survival. Pressure often kept them from writing critically about the local authorities, effectively transforming them into government public-relations services.

That dynamic also created a niche for independent coverage of the regions.

“Many good journalists [who did not want to work for state-funded news outlets] were now out of work and looking to collaborate with civil society activists to create a new independent media outlet,” Sofia Kropotkina, who joined 7×7 Horizontal Russia a year after its 2010 founding, told me over coffee in Vilnius.

The publication was founded in the city of Syktyvkar, in the vast northern republic of Komi “to report on how civil society operates in small regions,” she said.

A province where the Soviet authorities had sent many prison laborers, Komi possesses a strong civic spirit, she says. The stories 7×7 published cast light on the many small victories local civil society activists achieved battling the state bureaucracy—from pressuring officials to build paved roads between villages to improving conditions in orphanages.

Over the years, 7×7 formed teams in various regions across the country, employing correspondents in 30 cities by the start of the war. 7×7 also hosted annual festivals where activists from many regions for causes from animal rights to the environment could meet and exchange stories. The publication survived on small grants and commercial contracts. Not having to pay high Moscow salaries eased financial strains.

“We basically cover all the regions west of the Ural Mountains and north of Rostov,” said Grigorenko, who became chief editor in 2020, two years after joining the publication as a correspondent in his hometown, Voronezh.

“When I worked at Kommersant [prior to joining 7×7], I began to realize how Moscow would look at the regions from the top down—‘we make all the decisions here, and you live there how we allow you to live.’”

“7×7 looks at the country from the bottom up, at how federal decisions affect people in the regions and how people in the regions are trying to assert their rights.”

While 7×7 was never expressly oppositional, it would still often face pressure from the local authorities. Once, the publication was fined for an article published in the indigenous Finno-Ugric Komi language, still spoken by roughly 150,000-200,000 people. Russian law requires media outlets to obtain a license for publishing an article in a language other than Russian, which Kropotkina believes is a way of suppressing indigenous languages.

While 7×7 was never expressly oppositional, it would still often face pressure from the local authorities. Once, the publication was fined for an article published in the indigenous Finno-Ugric Komi language, still spoken by roughly 150,000-200,000 people. Russian law requires media outlets to obtain a license for publishing an article in a language other than Russian, which Kropotkina believes is a way of suppressing indigenous languages.

A much smaller operation but built on similar principles, People of Baikal was founded by Trifonova and her colleagues in 2020 to cover grassroots initiatives and local politics in Siberia.

“We wrote stories about how people lived in the depths of the country for an audience of people who lived in major cities,” she said.

Residents of Russia’s regions are often angered by the obliviousness of Muscovites, she says. Residents of Moscow and St. Petersburg often call Russia’s far-flung provinces glubinka, which literally translates to “the depths.”

“The budget for Moscow’s lawns is larger than the public-services budget for entire cities [in the regions]—and that is unfair because Siberia has vast natural resources,” she told me. “But villages still don’t have natural gas and people heat their homes with firewood.”

“The regions pump out the resources, and the center gives nothing in return, so people live very poorly,” she added. “There has always been a feeling that Moscow looks at the regions like we’re a barbaric colony.”

Grigorenko of 7×7 shares the same sentiment.

“It’s a strong metaphor but at times it feels like people in the regions perceive the state government as an occupying force,” he said.

For Trifonova, the war felt like “a logical conclusion of all of these processes.”

She described the absurdity of how Muscovites continued to go “to their coffee shops and restaurants in Patriarch’s Pond [an affluent neighborhood of Moscow]” while mass graves pullulated across Siberia. “You begin to feel these are two separate nations, two separate realities.”

Decision to leave

Shortly after Russia invaded Ukraine, the entire 7×7 editorial team flew from all corners of the country to Istanbul to take part in their planned retreat. Within two days, the Russian government blocked domestic access to their website, prompting conversations about to how the publication would exist in the context of the war. Some journalists, like Kropotkina and Grigorenko, decided to apply for visas to Europe. Others chose to return to Russia despite the risks and continue to work anonymously.

“Because we all worked remotely already, the idea of having our colleagues spread across several countries did not seem as daunting,” Grigorenko said.

Perhaps due to its small size and remote location, People of Baikal did not immediately catch the Kremlin’s attention, allowing Trifonova and her colleagues to remain in the country and continue their work. In the wake of the mass exodus of journalists, the importance of independent coverage in Russia grew daily.

“It was certainly scary,” she said, “but from a professional standpoint, it was a great opportunity.”

Trifonova and her colleagues became the first Russian journalists to write about hidden graves and cover funerals for Russian soldiers serving as volunteers. The first funeral—held at a children’s archery range in the Buryatia Republic’s capital city Ulan Ude—was a “shocking sight.” Buryatia, where archery is a popular sport and Tibetan Buddhism is practiced, is home to the Buryat Mongolic ethnic group.

After the funeral, parents complained that the smell of corpses lingered over their children’s archery training.

Even prior to Russia’s 2022 mass invasion of Ukraine, journalists chronicled how the state would discreetly send Buryat soldiers to fight alongside pro-Russian militias in Ukraine’s Donbas, where Moscow had been fomenting a separatist conflict since 2014. Some observers have accused Moscow of conducting “double genocide” by sending indigenous ethnic minorities to the front lines in Ukraine.

“We see this as a colonial war that hurts all of Russia’s ‘colonies,’ not just Ukraine,” Trifonova said. “Ukraine is also a colony, but one that resists, whereas [Irkutsk and Buratiya] are colonies that continue to obey.”

Buryatia is second only to the impoverished North Caucasus region of Dagestan in terms of the number of its men killed in Ukraine.

“Poverty enables the Russian army to exploit [the regions],” Trifonova said. “There are villages where over half the men are jobless, and unlike poorly paid temporary construction gigs, the military promises attractive benefits.” Since the start of the war, there has been a noticeable absence of men in many Russian villages.

It’s likely the publication of a verified list of men from the Baikal Region killed in Ukraine prompted the authorities to crack down on People of Baikal.

“We began this list because it was obvious that the Defense Ministry was deflating the official numbers,” Trifonova told me. “All too often, we would hear locals speaking about losing their loved ones and we knew there was more to the story than the government was revealing.”

Cross-referencing local reports with information relayed by relatives of soldiers, Trifonova and her colleagues confirmed nearly 2,000 unreported deaths from the Baikal Region before they were forced to leave Russia. Names, ages and occupations were listed underneath photographs of the fallen soldiers. Many are very young, between the ages of 18 and 22.

The work was grueling and often depressing, but positive feedback and support from locals kept motivating Trifonova and her colleagues to continue reporting on how the war was devastating their home region. Grandmothers would show up to their office to donate pension money, she said.

“You’re on the verge of tears, and you don’t want to accept the money, but [then the women] tell us, ‘I need this, please keep writing,’” Trifonova said. “Our readers feel less lonely when they realize they aren’t the only ones against the war.”

Trifonova felt especially helpless when she was forced to reckon with the idea that she would not be able to return after the Federal Security Service (FSB) raided her office. “Even before the war, we were so used to helping people; I could write a story about a mother who had no access to the right medication for her son, and then a local official would call me and tell me that he would take care of it,” she said. “Now I was suddenly in a position where I was the one who needed help, and it was difficult for me to wrap my head around this.”

Riga’s Media Hub

I first saw Trifonova sitting alone in a podcast recording studio in Vilnius’s Media Hub. Seeing her caught me off guard as I recognized her from a 2022 PBS documentary about journalists and activists who remained in Russia despite the obstacles.

In Riga, Trifonova lives alone in a “small but livable studio” and is in the process of obtaining a residence permit with Media Hub’s help.

“It’s difficult to describe in words how grateful you are to people who help you when you end up in a foreign country, with absolutely nothing, feeling paralyzed without a future,” she said.

Media Hub was conceived to protect journalists from around the world at a time when the profession was becoming increasingly risky, Sabina Sile, a Latvian activist who cofounded the organization in 2019, told me. Initially, it sought to support up to seven journalists per year but the war in Ukraine forced it to dramatically expand operations.

It now supports 270 journalists and their families in Latvia, the majority from Russia. Although younger than many of the journalists at the hub, Sile waltzes around the coworking space like a community matriarch, checking in on the journalists and greeting them in Russian.

The hub assists the Latvian government vetting journalists seeking humanitarian visas. Media Hub checks their professional qualifications and the government completes security checks. While a humanitarian visa enables journalists to enter the country, they must still obtain a residence permit to be able to work and pay taxes in Latvia.

Sometimes they receive pushback from various Latvian political factions. Events in Ukraine often prompt the government to change its position, Sile says. Compelling evidence that Russian soldiers committed brutal war crimes in the Ukrainian cities of Bucha and Irpin, for example, compelled the government to issue a new restriction for journalists seeking residence permits.

According to the new law, two Latvian government ministers must agree that a journalist will be doing work “in the interest of the Latvian state,” Sile said. That means sports or culture journalists who fled Russia because their lives were at risk either due to mobilization or because of their political position may now be unable to obtain residence permits.

But those who do receive permits “can breathe,” Sile added, as the ability to pay taxes and access medical support eases the psychological stress that comes with arriving in a new country. “The lack of certainty is very psychologically damaging for the journalists, especially those with families,” she said. “They need to plan ahead.”

Media Hub also offers psychological care programs.

“Journalists fleeing Russia arrive in a fight-or-flight mode,” she said, pointing to a photograph of a wellness retreat, where journalists have hiked through a forest together near the Baltic Sea. “It’s hard for them to absorb new information about media management when they are thinking about survival.”

Both Ukrainian and Russian journalists have exhibited high levels of PTSD. “We offer them a comfortable office so they can recover before symptoms worsen,” Sile said.

The working area is free of separating walls,and the windows on either side of the space provide plenty of natural light and a sense of transparency. Sile made it a point to take me to the women’s bathroom to show me the feminine products.

But it remains a major challenge that the Latvian authorities have had little precedent for dealing with such a specific humanitarian crisis of this scale.

“Ideally, we should have already developed a special mechanism for helping journalists from Belarus, Russia and Ukraine, but due to a lack of time and political will, [the authorities] keep trying to fit this phenomenon into an existing mechanism,” Sile said.

In neighboring Lithuania, where both Kropotkina and Grigorenko were able to swiftly secure journalist visas, the situation is different.

“Lithuania already had accepted thousands of refugees from Belarus in 2020,” Grigorenko told me about the mass exodus of Belarusians following authoritarian leader Aleksandr Lukashenko’s brutal crackdown on civil society.

In Latvia, Media Hub helps the authorities by explaining to officials the backgrounds of aid recipients. When the government sought to restrict access to humanitarian visas for those who applied in the summer of 2022, the reasoning was that all those who needed to flee Russia had already done so.

“We needed to explain to them that there are many reasons journalists couldn’t leave immediately—like people who had sick relatives or children,” Sile said. “Money is also an issue: it’s one thing if you live in Moscow and can find a cheap flight to Europe, but it’s another if you’re a regional journalist who needs to scrape together 1,000 euros for a flight from Siberia.”

Proportionally, Latvia already had one of the largest Russian-speaking populations outside Russia, second only to Belarus. Soviet-style canteens serving pelmeni (meat dumplings) and all the other greasy delights of Russian cuisine can be found in many corners of the city.

The ornate Art Nouveau buildings in the Riga’s 19th-century Centrs neighborhood resemble their counterparts in St. Petersburg. The seaside town of Jurmala, where pine trees surround triangular-roofed wooden cottages, continues its Soviet-era tradition of housing intellectuals from Russia’s capitals. The Soviet-born Russian pop singer Alla Pugacheva, whose popularity in Russia eclipses that of Madonna’s in the United States, is one of the many prominent Russian anti-war figures who spends time there.

Many journalists from Moscow and St. Petersburg told me that Riga offers them many comforts of home in addition to the free air of Europe. But for Trifonova, for whom the western part of Russia already feels like a separate country from her native Siberia, Riga seems alien.

“For us, it was always quicker and cheaper to fly to China than Moscow,” she told me.

“I just want to go home and continue my work,” she said, pausing as if to hold back tears. “I fall into depression when I think that this can drag on for another ten years or longer.”

I have heard many Russian émigrés express longing for their homes, but never with such conviction and sincerity. Back in Siberia, Trifonova’s husband—who is taking care of his own sick mother—and 18-year-old daughter remain. Their future, too, is still unclear.

Reporting on Russia from abroad

Although access to the websites of 7×7 Horizontal Russia and People of Baikal are now blocked in Russia, both outlets have experienced a major growth in readership.

Across the board, Grigorenko says that 7×7’s audience has grown seven times over during the past year, and like People of Baikal, the publication has diversified by expanding to the platforms Telegram and YouTube and occasionally using mirror websites.

“Demand grew because ‘enlightened’ news readers [from Moscow and St. Petersburg] suddenly began to realize how large the gap is with the rest of the country that lives in a ‘grey zone,’” Grigorenko said. Many Russian émigrés wonder why people in the regions “don’t perceive the war as a tragedy.”

7×7 now relies on anonymous contributors for its reporting. Some are journalists, others activists. “The war has made it difficult to separate journalism from activism because speaking the truth is now a form of protest,” Grigorenko said.

One example of recent work is an investigative long read about institutional racism in Russia titled “The Non-Russian World.” The name derives from the “Russian World,” denoting the perceived Russian cultural sphere of influence Vladimir Putin has pledged to protect. Critics of the concept—now widely debated in the context of the war—claim it does not factor in non-ethnic-Russian nationals, who constitute roughly 20 percent of the country’s population.

In one example in the report, a Russian production company shared a casting call for an actor with an “ethnically Slavic look” to play the famous cosmonaut Andriyan Nikolaev, who was an ethnic Turkic Chuvash.

The report also notes that instead of addressing issues that concern ethnic minority communities in Russia, such as the demise of their languages, the government engages in the “festivalization of national politics,” financing monthly cultural festivals that superficially portray Russia as a pluralistic society.

Like People of Baikal, 7×7 has been tallying military deaths, including publishing the first investigative report that confirmed Russian military conscripts had been killed in Ukraine despite claims by Putin and the military that only contract soldiers—and later mobilized men—were fighting there.

Conscripts are the youngest and least experienced category of servicemen, typically young men between the ages of 18 and 22 who are drafted right out of school. “We published such a report not because we sympathize with our soldiers but because we want to expose the government’s lies to the Russian people,” Grigorenko said.

Trifonova and her colleagues continue to rely on their local readers to send them news from Siberia. In one recent incident, readers from a town in the Irkutsk Region described how a school administration erected a public “board of fallen heroes” from the war in Ukraine, featuring the slain fathers of local schoolchildren.

“Some kids fainted from grief,” she said.

Other readers send photographs of gymnasiums converted into military training sites where children are taught to assemble rifles. Teachers are in shock, she says, but school administrations continue to enforce such policies. “Math and literature teachers are forced, at the expense of their own lessons, to send these kids to military training, where kids learn how to wear gas masks.”

With the help of local volunteers, typically men between the ages of 40 and 60, People of Baikal continues to keep tallies of military burials and clandestine gravesites. Like 7×7, it preserves the anonymity of local subjects and correspondents to protect them.

That’s often a problem for for journalists who want to see their bylines. “Anonymizing is psychologically difficult because at the end of the day, all journalists want to be published,” Grigorenko said. “But we will never denanonymize them because we do not want to put them at risk.”

“Now you have to put your ambitions to the side because it’s imperative for us to gather information from Russia, so the country isn’t just whited out,” Trifonova said. “Otherwise, here in emigration, we will totally sever ties with our country.”

The wealth of contacts both People of Baikal and 7×7 have in the regions also gives them an upper hand over bigger outlets. With virtually no on-the-ground correspondents, covering events within Russia has become increasingly difficult for everyone.

In late June, when Evgeny Prigozhin—the recently deceased head of the Wagner paramilitary organization—attempted to stage a mutiny, Ilya Barabanov of BBC Russia said, he and his colleagues were scratching their heads over how to cover the historic moment. “We just had no one in Rostov [the southern city Wagner troops breifly occupied] to report to us what was happening.”

However, both People of Baikal and 7×7 were able to swiftly file firsthand accounts that conveyed on-the-ground reactions to the attempted rebellion in various cities across the country.

A day after purported Ukrainian drone strikes caused a major explosion in the Russian border city of Pskov in August, Dozhd TV quoted a firsthand account by an anonymous People of Baikal correspondent.

But in an increasingly totalitarian and mistrustful society, the dangers for correspondents on the ground are growing daily. On several occasions, relatives of killed soldiers to whom Trifonova’s colleagues spoke would denounce the journalists to the authorities the next day for “discrediting the army,” a charge that carries a prison sentence of up to 15 years.

Sometimes, People of Baikal receives offers from people posing as potential volunteers who ask questions about anonymous contributors or local opposition. “We immediately understand that these are guys from the Federal Security Service (FSB). Comrade major [an FSB rank] is sniffing around,” she said chuckling.

But despite the risks to their contributors, both Grigorenko and Trifonova believe it is vitally important their publications continue to cover the country.

“We are working dispel to our readers the notion that if a revolution happens in Moscow, the rest of the country will adapt,” Grigorenko said. “No, they won’t adapt—if people in Voronezh or Tyumen don’t learn how to make decisions for themselves, we’ll be cursed to endure this vicious cycle of [militaristic dictatorships].”

For People of Baikal, Trifonova says, the goal is to raise awareness of anti-war sentiments, and explain to people still living in Russia how they can be useful. “We need to show our readers that claims that the majority support the war are not true, that there are people who are willing to do something to resist,” she said.

“It’s not true Russia is a country filled with orcs [a derogatory term for Russian soldiers] and monsters,” she says. “People are just afraid to speak the truth and disoriented about whether they can do anything.”

Top photo: A mocking depiction of Vladimir Putin hung by Latvian activists across from the Russian Embassy in Riga