DUTSE, Nigeria — On a hot Saturday morning, I visited a government girls’ secondary school in this town on the outskirts of Abuja. There is not much to see except for the market and people selling food and goods along the unpaved, bumpy roads. I traveled there with Bella Ndubuisi, the founder of a leadership development program—Girl Lead Hub—that would be taking place there. During the drive, we discuss Bella’s motivations and activities. Girl Lead Hub provides a support network for girls aged 13-21 aimed at enabling them to grow to their fullest potential. The sessions take place once a week for six weeks with the goal of helping girls “rediscover themselves, form strong bonds of sisterhood and take bold and steady steps toward realizing their goals for the future.”

I came here to observe how girls are being taught to stand up for themselves in school. I’m learning that although empowerment means different things to different people, it is mainly about equipping girls with the knowledge and skills they need to live better and more productive lives. In this case, that means teaching girls about self-esteem and giving them opportunities to reflect on their activities and the happenings around them (through keeping journals and taking part in discussions). Most notably, engaging girls in role-play activities—as was done during the session—helps them visualize the challenges they experience, and practice their communication and negotiation skills.

In Nigeria, girls are not taught to speak up for themselves. Therefore, they go through childhood and adolescence with several issues bottled up inside. The lack of basic needs, including food and sanitary supplies, makes them vulnerable to sexual abuse and assault. Programs like Girl Lead Hub already show evidence of positive impact. But because it operates on private funds, it risks reaching only a select group of girls and even leaving out the most marginalized ones who are not in school.

Leadership programs must also incorporate comprehensive sexual and reproductive health education and life skills to address the health and economic challenges girls face. There is a need for structured mentorship programs to provide girls with mentors who can help them transition from adolescence into adulthood. The government (specifically, the ministries of education, women affairs and social development) complains it does not have adequate funds to provide the amenities girls need, even clean toilets and WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene) facilities, safe classrooms and scholarships. That’s why there’s a need for public-private sector partnerships, including with groups such as Girl Lead Hub, to advance girls’ wellbeing by instituting programs at school and community levels.

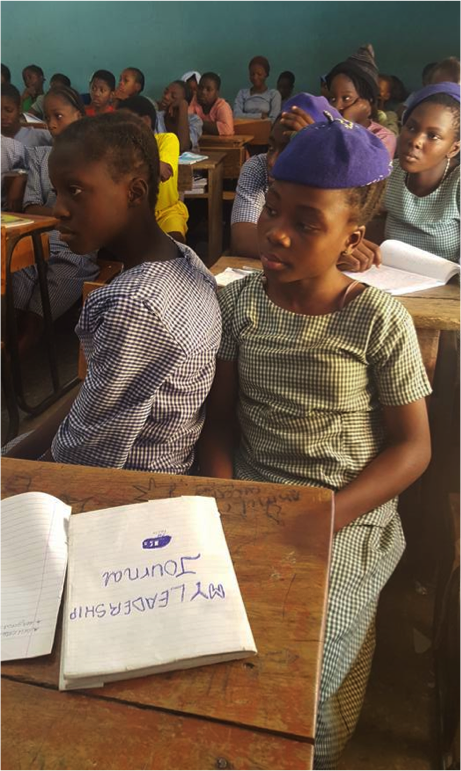

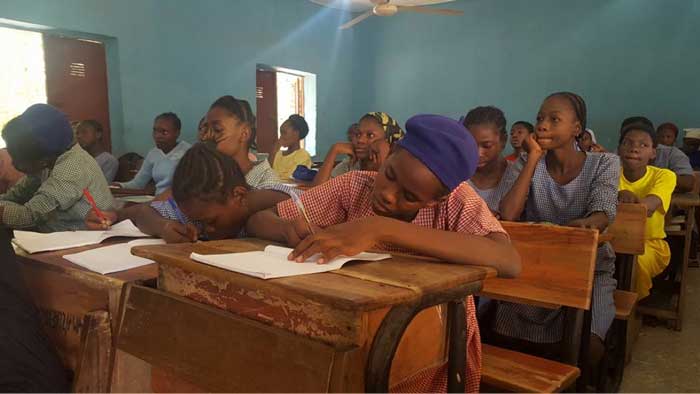

Classroom exercises

Bella’s classes began with 45 girls during her first visit to the school earlier this year. By the end of the six-week program, the group had grown to 130 girls as participants invited their friends to join. The curriculum focuses on public speaking, communication, writing, self-awareness and service. Bella also provides tutorial sessions to the girls as needed, especially focused on STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) subjects. Outside the in-school leadership program, she also mentors a group of about 10 adolescent girls and teaches them how to share their stories through her #WhenGirlsWrite initiative. The girls work together to raise funds for university scholarships, and Bella connects them to internship opportunities.

A tall Igbo woman, Bella is in her early thirties. She is one of four girls from a middle-class family of six children. She grew up in a big city in eastern Nigeria known as Aba in Abia state, an economically vibrant place often referred to as the Japan or China of Nigeria because of its booming manufacturing industry. Bella, who wanted to become a United Nations ambassador as a child, remembers attending a public elementary school and how competitive it was, a stark contrast to the present state of public education in Nigeria. “I’m meeting a lot of young girls who are having this sort of dream that I had as a kid, even bigger,” Bella says. “But I just worry that maybe it’s just words to them and that perhaps they don’t understand what it literally means to be in that field. And, they will benefit from having somebody who’s walked through [the process] to help shape them up. That’s why I started [Girl Lead Hub].”

For the next academic year starting in September, Bella plans to create a more structured program. The formal course will require an interview to ensure that selected girls have strong academic backgrounds and interest in leadership. She is also expanding the network to include about 15 girls from Rwanda whom she met during a recent trip to the country and who would interact with Nigerian Girl Lead Hub mentees via a Facebook group to share trans-national and trans-cultural experiences.

Watching Bella in class in her knee-length yellow-and-brown African print dress with her natural hair in tiny twists, I could sense excitement and a sense of belonging among the students. The first thing Bella asks them to do is bring out their journals. Some moaning erupts, and it soon becomes evident that many of the girls had not written in their journals. Bella had assigned them to describe their daily experiences and interactions in an exercise book in order to help them pay better attention to the events around them. Bella proceeds to hand out a survey on self-esteem with questions asking the girls to rank how they feel about their bodies and what they would change if they could. Then Bella begins her lecture, asking the girls, “Why do we care what people think about us?” A student in a yellow-checkered shirt and skirt uniform—the uniform colors represent the residence hall each girl belongs to—responds, “It bothers me a lot because I think what they’re saying is true.”

I’m moved by the story of another girl in a green uniform and camouflage headscarf who, with dejection clear on her face, describes how she had wanted to go to a “gifted school” but had to attend the “normal” government school because her parents could not afford the fees. She felt bad that people had thought it was because she did not pass the entrance exam. One of her classmates encourages her by saying, “It’s not great schools that make great people. It’s the people in those schools that make the school great.” Before the end of the three-hour class, the girls act out a role-playing exercise addressing perceptions of beauty. They conclude by reciting: “I am a strong-enough girl. I can achieve anything. I am intelligent and I dominate my sphere.”

Controversial topic

The topic of girls’ empowerment prompts mixed sentiments in Nigeria. A woman I spoke with during her visit to Abuja from Lagos told me that when we talk about empowerment, we must define what it means. “What are we empowering the girls to do?” she said. I once sat down with 12 junior secondary school students (aged 12-15) during a drop-by visit to their schools in Lagos and Abuja and asked them to tell me their understanding of the term “empowerment.” It is providing free education, free vocational training, not sending children to hawk goods during school hours or after school, and no pre-marital sex and early marriage, they answered. When I asked the students what makes them feel empowered, they told me it happens when they have someone to advise and talk to them. They particularly emphasized their desire for mothers to speak with their daughters, something they feel doesn’t happen often enough. The challenges they and their adolescent peers face include lack of menstrual pads and other personal items, and protection from harassment and molestation by boys and men, including their own teachers. “A girl can be forced to do what she does not want to do,” one girl wrote. “Especially when she is staying with her uncle or auntie. Sometimes, it may be our teachers in school forcing a girl to sleep with him just because of marks to pass a class or subject. Or a boy who is asking you for friendship and you did not agree. He can gang up and beat you.”

Sexual violence and abuse occur at very high rates around Nigeria. A 2015 country survey on violence against children showed that one in four girls and one in 10 boys have experienced sexual violence before the age of 18.[1] An organization called Girl Pride Circle recently hosted a program called “Safe Kicks Initiative: Adolescent Girls Against Sexual Violence” in which adolescent girls were educated about sexual abuse and taught Taekwondo skills for self-defense. A six-month program partly funded by a seed grant from the women’s rights advocacy organization Women Deliver, the Safe Kicks Initiative helped 250 adolescent girls in five secondary schools in Lagos state tackle sexual violence with support from key community stakeholders. At the end of the project, participants developed action plans that were presented to community leaders.

The founder of Girl Pride Circle said that 592 of 845 female patients seen at a leading sexual assault referral center in Lagos state between 2013 and 2015 were adolescents. The biggest challenge many Nigerian girls face is enduring abuse in their homes and communities, often without anyone willing to listen to and help them. Girls are also often blamed for being victims. “What were you wearing?” “You should not have gone there by yourself!” “Are you the first person to be touched?” “I won’t allow you break up my marriage [with your allegation].” Those are the kinds of responses girls get when they try to speak out about abuse. Unfortunately, women are often the ones who attack the victims. A teacher at a remote public school in Abuja I visited in February told me about the girls in her school, many of whom work as domestic helpers. The caretakers of these girls (particularly women) often do not buy underwear for them, with the explanation that they do not have money, leaving them vulnerable to abuse as they walk to and from school and even in school. The teacher, who serves as a counselor at the school and coordinator of extracurricular activities, engages non-profit organizations to provide these basic items for the girls. But she tells me that several parents who want to maltreat the girls and/or feel she is interfering in their private lives have rebuked her.

Taekwondo skills (Photo courtesy: Girl Pride Circle)

The girls I met at the two schools in Lagos and Abuja re-emphasized the teachers’ point about maltreatment. The “aunties” many girls live with (usually relatives, but in some cases family friends) task them with strenuous chores that cause physical pain and often cause the girls to go to school late and tired. The girls are also beaten for their actions and their general wellbeing is neglected. “They don’t have time for us,” one girl says. Such demeaning treatment surely affects girls’ ability to learn in the classroom. In my experience, girls are often open to speaking about abuse. But very little to nothing seems to be done to protect them. As another girl states, “The girl child does not get enough backing up. So even though [we] want to be great, lack of support makes girls to be inferior and does not enable growth due to the community and surrounding around the girls.”

While some people see the need for empowering girls, others find it threatening. One male principal of a private Christian school in central Abuja told me during a visit to his office that he is scared of the idea of making girls strong. I had gone to the school to request an opportunity to meet and chat with the female students. As we spoke, I mentioned my interest in girls’ empowerment and that led to his comment. He sarcastically asked me if empowerment meant that women would start beating up men. I left his office wondering if he was being serious. But I could sense his uneasiness with the subject.

Bella tells me that while most of her students’ parents have supported her work with the girls, many of them “don’t understand what this could potentially mean for their kids.” One father told her not to call his daughter again. I ask why and she shrugs her shoulders, saying, “I don’t know!” Although the girl’s parents have asked her to leave the program, she insists she still wants to be part of Girl Lead Hub. Even the girls, Bella says, sometimes show apathy. “Girls think it’s too early [to be engaged in leadership and public service].” They ask, “Do we have to? Do I have to write that piece?”

So what exactly can girls’ empowerment do for them in Nigeria? Recently, one of Bella’s 18-year old mentees joined about 2,000 Nigerian youths in a peaceful protest advocating for the passage of a #NotTooYoungToRun bill. The legislation would reduce the minimum age for Nigerians to be able to run for political office— for president from 40 to 35 years, governor from 35 to 30, member of the House of Representatives from 30 to 25, and State House of Assembly from 30 to 25 years.[2] Both the National Senate and House of Representatives passed the bill a few days after the protest. In an opinion piece submitted to a local newspaper, the 18-year-old states, “Having witnessed the positive outcome of the #NotTooYoungToRun campaign, I will begin to prepare and build myself, knowing that in a few years, I, too, will be eligible to run. I will also raise awareness of the age-reduction amendment, and support other politically aspiring youth who are now #NotTooYoungToRun.”

peaceful protest (Photo courtesy: Premium Times)

Bella wants to prepare girls for leadership roles. But as she notes, it is one thing to aspire to a leadership position and another to actually possess the skills for leading. I ask Bella how she would describe the characteristics of a typical Nigerian girl. She tells me there are differences based on the cultural and social norms in various parts of the country. “A girl in the southeast is more self-conscious, independent-minded, and more assertive than a girl in the northern part of the country. A northern girl is smart but she is not open-minded. They won’t give you details unless you pull the details out of them.” These differences are a result of the diverse cultural ways in which girls are brought up. While some are nurtured for lives of domestic servitude and home-making, other girls are encouraged to pursue academic and career success. The religious and social culture in northern Nigeria helps produce girls who are conservative. There are some rare examples of girls who have broken out of those molds. But it usually takes leaving their home environment for them to take up leadership roles. Bella’s work is contributing to taking girls steps closer to not just having a seat at the table but also having a voice there.

As we drive out of the school premises, we pass rows of clothes spread out across the green lawn. That is how students dry their laundry after washing. A large crowd proceeded from the residence halls heading toward the dining hall. It was lunchtime.

[1] http://www.togetherforgirls.org/country-partners/nigeria/. Accessed: 02/08/2017

[2] http://yiaga.org/nottooyoungtorun/the-not-too-young-to-run-movement-commend-the-nigerian-senate-for-the-passage-of-age-reduction-bill/. Accessed: 02/08/2017