September 17, 2015

Painter Adel El-Siwi leads me through his workspace on the fourth floor of a downtown Cairo apartment building. His hands, cargo shorts, pink T-shirt, and Crocs are splattered with paint. Shelves of art, literature, and philosophy books reach the high ceiling. Across the corridor, massive canvases face the wall like unopened presents. Tubes of paint are meticulously ordered on a shelf near the kitchenette. We walk toward the salon, where two of his framed paintings hang, between more books and alongside the work of Egyptian artists, the late modernist Mounir Canaan and the young innovator Hany Rashed. Is it okay that I’m already sitting, I ask Siwi, wondering if I had broken decorum by getting comfortable. “I am standing because I am excited,” he says.

I’m not here to discuss his luminous career—exhibitions across the Middle East, Europe, and South America, paintings that critically integrate pharaonic and surrealist imagery in effervescently colored figures. No, today I want to ask him about the role of the intellectual in contemporary Egypt, in a political scene contracted by state policies anathematic to free expression.[1] Over the past half-century, how have intellectuals interacted with the state? What is the relationship between intellectuals and the state today?

I meet with Siwi toward the end of August, weeks after the government had urged Egyptians to celebrate the widening of the Suez Canal in a massive ceremony on August 6. “State of Optimism Among Intellectuals after the Opening of the New Suez Canal,” read one news headline.[2] A private gallery hosted an art exhibition themed “Long Live Egypt.” The majority of cartoonists conveyed their national pride in broadsheets. The cover of Egyptian Arts, the Ministry of Culture’s periodical, depicted the silhouettes of a crane and a worker, an everyman, standing alongside the canal. Suez Canal banners were draped on museums and theaters, hotels and office buildings. When I ask Siwi about the nationalist wave, he tells me, “The whole orchestra is going with the main melody. There is no other melody.”

On that score, Siwi published a defiant polemic in the state’s flagship newspaper Al-Ahram, entitled “The Legitimate Intellectual” on August 9. The painter used his twice-monthly column to deconstruct a debate that had emerged in articles and broadcast reports between Minister of Culture Abdel Wahed El-Nabawi and prominent Egyptian artists, filmmakers, novels, and poets. Nabawi had sacked two senior officials. In angry columns, numerous intellectuals condemned the dismissals, criticized Nabawi’s five-month tenure, called for his removal, and threatened to protest before his offices. To calm nerves, Prime Minister Ibrahim Mehleb intervened and met with top intellectuals on July 27.

“I followed with interest the confrontations between the intellectuals and the Minister of Culture,” Siwi wrote in his column. By posing several rhetorical questions, the painter transcended the minutia of the highbrow quarrel and probed the role intellectuals should play in the face of an incompetent state. “Did the intellectuals demand that the Prime Minister clarify his position toward the growing autocracy, the censorship and obstruction of freedoms?” he wrote in Arabic. “Did [the Prime Minister] offer convincing answers to [the intellectuals], to questions such as: Why is censorship expanding; the spaces for disagreement shrinking; and the opposition and the competent ignored in order to support the half-talented?”[3]

Siwi argues that the debates percolating around the Ministry of Culture are at best petty, at worst a dereliction of duty. A handful of intellectuals had face-time with the Prime Minister at a moment of terrorism and state repression. Yet Egypt’s men of letters (yes, they are mostly men) focused narrowly on the incompetence of a single ministry, as if a better minister might revive a rotten apple. “I am astonished that the intellectuals do not stand in protest of the continued detention of innocents in prison, which the president himself has admitted,” Siwi wrote. “Do the intellectuals close their eyes to these injustices and then eagerly open them—and become revolutionary—when demanding the minister’s resignation?”[4] Siwi’s questions shed light on the conflicted role of the intellectual in Egypt and their truncated voices against the backdrop of present injustices.

The State’s Intellectuals

Candidate Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi met with a group of intellectual elites for a photo op in May 2014, at the height of his presidential campaign. “Thinkers and writers constitute the conscience and consciousness of Egypt, and they have a vital role to play in leading public opinion along with the help of the media,” he told the gathering, according to local reports.[5] The candidate’s official Twitter account added, “Egypt needs intellectuals, thinkers, and men of letters to play a very big role during the next phase, guided by national responsibility, and submitting to the interests of the country.”[6] Indeed Sisi’s rise to power depended on their support.

In early June 2013, intellectuals staged a sit-in outside the Ministry of Culture, which presaged a national protest movement against the Islamist President Mohammed Morsi. Artists and writers felt threatened by religious censorship and intolerance for dissent, which they dubbed the “Brotherhoodization” of culture. So when the Armed Forces took over the country a month later, throwing Morsi in jail, leftist and independent intellectuals cheered. Many cultural elites even signed an open letter that August calling the Muslim Brotherhood terrorists, ten days in advance of the authorities’ lethal crackdown on the Muslim Brotherhood protest encampments in Cairo.[7]

Painter Mohamed Abla signed the letter. He told AP in September 2013: “I’m still against a military regime, but we need the power of the army to save us from the Muslim Brotherhood.”[8] Abla had participated in the 2011 uprising against Mubarak and the Culture Ministry protest in June 2013. That fall, he sat on the committee that drafted a new constitution after Morsi’s overthrow.

A wide swath of intellectuals has continued to back authorities in spite of an ongoing clampdown on oppositions, media, and much more. President Sisi sat at a long wooden table chatting with intellectuals for over four hours in December 2014. “There was no red lines or green lines or lines of any color [defining] what we discussed. Every person talked about what they wanted, about any topic that they wanted,” one writer said on national TV shortly thereafter.[9] A handful of television spots and newspaper articles about the meeting conveyed the intellectuals’ solidarity with the president.

Of course such solidarity might not be surprising given Egypt’s ongoing battle against terrorism on multiple fronts. Support for the presidency is deeply tied to an anti-Islamist position and indeed secular intellectuals were under threat from the Brotherhood’s policies. Still, Western observers might expect intellectuals to offer detached reflections on the current regime’s authoritarian policies, especially as two years have passed since Morsi’s ouster and the Brotherhood is now decidedly enfeebled.

Ursula Lindsey, a reporter on culture in the Middle East, has explored why writers who were dissidents under Mubarak have today changed their tune. “Most intellectuals here continue to see themselves as guardians and spokesmen for an idealized strong state which they may criticize and oppose but which they cannot imagine life without and which they will rally to if persuaded that it is under threat,” wrote Lindsey in 2014.[10] Though a strongman runs the country, the state remains weak—ineffectual in battles against terrorists in the Sinai, unable to cope with a deteriorating economy. From afar, the Egyptian state does not seem under threat. But for artists and authors who faced threats from the Brotherhood, the fight against Islamism is ongoing.

Intellectuals in Egypt occupy an ambiguous role. Even the President, who praises them as the light of the nation, also derides them as out of touch. “I am departing from the [prepared] text so that I can talk to all of the Egyptian people not just the intellectuals,” said Sisi, switching to Egyptian colloquial dialect at the televised ceremony marking the Suez Canal’s expansion, in early August. “Some may differ with me, but I say to them that these simple people are the most important to me,” he continued.[11] In military uniform, he floated in a “Presidential Convoy and Naval Parade” as fighter jets rumbled above.[12] His populist appeal inadvertently drew out an important dichotomy between ordinary Egyptians and intellectuals.

The Arabic word for intellectual (muthaqaf) is derived from the root meaning, “culture.” Intellectuals are thus, “cultured ones,” implying refinement and education, members of the intelligentsia. Muthaqaf pertains to a social class as much as individual creators—usually artists, critics, musicians, playwrights, poets, theorists, and writers, sometimes actors and filmmakers. (Islamic scholars fall into a different category.) In Egypt, the archetype of the intellectual is secular and learned, old and typically male. There’s a generational implication to the word, too. When the president or newscasters refer to intellectuals, they seldom are discussing young, dissident creators, graffiti artists, or untenured professors, but rather writers of heft and national prominence. “The state chooses specific people to speak in the name of the intellectuals,” Siwi told me.

Of course there are cultural players who oppose official policies and the state itself, but these are not the ones who are elevated to the level of muthaqafin by the state or the media. What came out of the 2011 uprising in Tahrir Square was a new conception of public art and culture. For example, the 2012 documentary The Noise of Cairo captures the burst of expression connected to Mubarak’s overthrow and features numerous young artists—a choreographer, a graffiti artist, a musician, and so forth. The opportunity of self-publishing, online expression, and public performance allowed a new generation of intellectuals to experiment as they gained international prominence.[13] Yet the truism oft-repeated by interviewees in The Noise of Cairo—that everything had changed since the 2011 revolution—is now stale. Since the 2013 ouster of Morsi, authorities—through censorship and crackdowns on public gatherings, among other tactics—have vaporized much of the ad-hoc artistic expression that emerged from the revolution. As the choreographer Karima Mansour said in the film, “[Artists] are feared by the government and the army… because artists are loud and they make a lot of noise.”

In contrast to the emergence of artist-activists documented in The Noise of Cairo, many Egyptian artists remain supportive of the regime. The historical role of intellectuals in Egypt has frequently veered toward the status quo. In her seminal study of the Egyptian art world, Creative Reckonings, anthropologist Jessica Winegar explains the “values (and tensions)” of cultural producers, which are rather different from a Eurocentric conception. She writes:

[T]he idea of the modern artist as translated in Egypt was one of a freethinking individual, but also a member of mainstream society—not an oppositional or critical malcontent. Thus, Egyptian artists have not emphasized the “rebel artist” strand in Euro-American ideologies of the artists, which is related to concepts of individualist personhood… Artists in Egypt did cast themselves as especially inquisitive, cultured, and productive. For them, art was a means of individual expression, but it was also a way to become respectable elite members of their society and contributors to their nation.[14]

Winegar’s observation is fitting of other members of the creative sector, many of whom historically have depended on the state’s support for their activities. This is one reason why the Ministry of Culture has become a site of conflict for the intellectuals.

The Intellectuals’ Ministry

The Egyptian state has been the primary benefactor of the arts since President Gamal Abdul Nasser established the Ministry of Culture in 1958 as part of his socialist reformation of the country.[15] The ministry has played a political role since its origins.

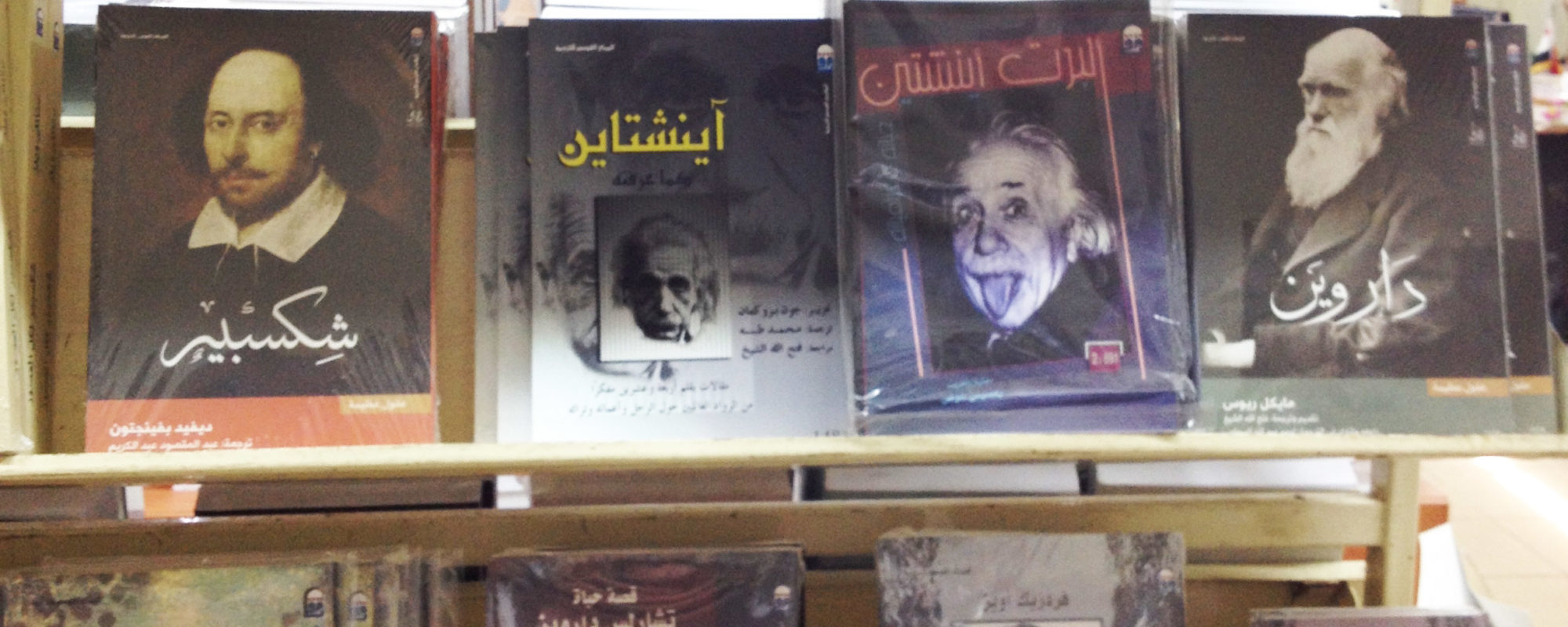

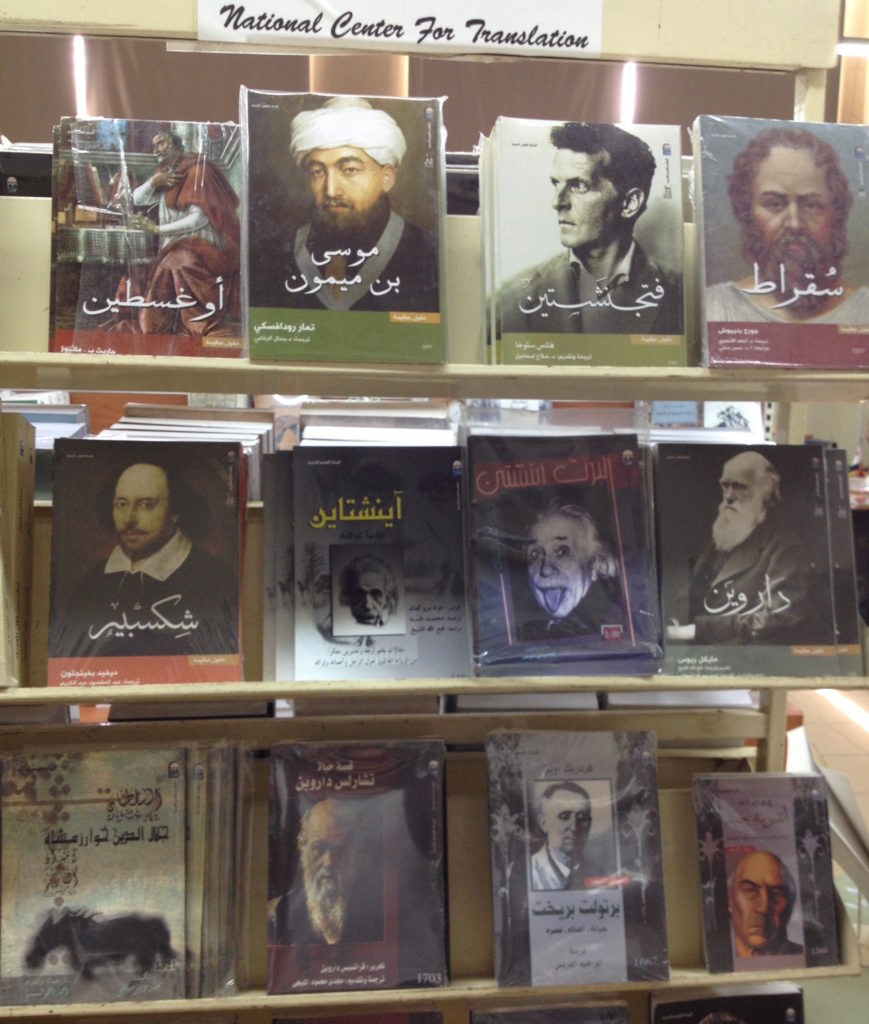

Today, the Ministry of Culture employs between 34,000 to 40,000 individuals and manages a USD190 million budget, 85 percent of which goes toward salaries. The ministry runs dozens of museums and 575 cultural palaces throughout the country (only about 300 are operational). There is also the Egyptian General Book Organization, a publisher which hosts the Cairo International Book Fair and prints several cultural magazines; the National Center for Translation, which has translated thousands of books to Arabic—from Jacques Derrida to an illustrated Adventures of Tom Sawyer. The ministry also oversees the National Library and Archives, Cairo Opera House, the Egyptian Academy of Arts in Rome, a number of galleries and theaters, and many high-profile events widely covered in the local media, including the Egyptian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale.

Nasser recognized the importance of crafting a new state-supported culture that was anti-colonial and anti-imperial, a break from the monarchy’s Eurocentric approach to fine arts, in order to complement socialist policies in other realms. Investing heavily in a new cultural infrastructure, Nasser worked closely with a coterie of talented artists, musicians and thinkers who remains the country’s most beloved to date. “Egypt was the first to make a concerted effort to co-opt its intellectual class,” critic Robyn Creswell has written. “Following the Free Officers’ Revolt of 1952, Nasser’s regime nationalized the press, the cinema and most publishing houses, establishing what one historian has termed ‘a virtual state monopoly on culture.’”[16] Even though Nasser jailed some opponents and intellectuals, their contemporary colleagues cherish his cultural legacy.

In the 1970’s, Nasser’s successor Anwar Sadat implemented neoliberal policies and gutted much of the Ministry of Culture.[17] Further, his signing of the Camp David Accords with Israel in 1979 angered many intellectuals, though Adel El-Siwi pointed out that intellectuals had parted ways with Sadat long before the peace treaty in part because he defunded cultural programming from film to theater. In contrast, Hosni Mubarak reinvested in cultural programs with an emphasis on youth production and modern art, raising the profile of the local scene globally.

From 1989 to 2011, the abstract painter Farouk Hosny served as Culture Minister. When chin-wagging with artists and curators, I heard many tales of corruption in the ministry during his two decades at the helm, including large commissions for Hosny’s inner circle and the unsolved theft of Van Gogh’s “Poppy Flowers” from the Mahmoud Khalil Museum. While in office, intellectuals wrote open letters calling for Hosny’s resignation.[18] Tens of millions of dollars passed through the minister’s account unaudited.[19] His bid to serve as UNESCO chief faltered due to instances of censorship and allegedly anti-Semitic remarks.[20] His closeness to President Mubarak’s wife Suzanne meant that he remains associated with the overthrown regime.

Managing a centralized and relatively efficient ministry, Hosny got a lot done. He established 42 museums and 125 libraries. He launched ongoing megaprojects, including a new antiquities museum near the Giza pyramids and a museum of Egyptian civilization in Fustat. He initiated the annual Youth Salon to support emerging artists. “Under Farouk Hosny, you could say the Ministry of Culture thrived,” the visual artist Huda Lutfi told me—a surprising bit of praise from an artist who is critical of the ministry and avoids interaction with official circles.

Hosny, 77, keeps an office in a villa in the upscale island of Zamalek. Inside are scores of sculptures and framed paintings. The prize of the lot: two small paintings by the early twentieth century Alexandrian painter Mahmoud Said, whose works sell for millions at auction. Hair dyed dark, Hosny wore a textured sport coat, blue button-down, tortoise aviator-style glasses, and suede loafers with no socks. Speaking in Arabic sprinkled with French, he explained the importance of ministries of culture, citing examples in France, Spain, and China. He quickly acknowledged the Egyptian ministry’s mistakes, especially the decision in January 2011 to carve out a distinct Ministry of Antiquities to manage Egypt’s vast archeological wealth, thereby siphoning off crucial funding for cultural activities.

Since the 2011 uprising, seven men have attempted to govern the ministry, and none of them can claim success. When I asked Hosny about the motley crew of ministers who succeeded him since 2011, he laughed. “The Ministry of Culture needs to develop a productive vision and to find a new identity,” he told me while sipping green tea. “How can Egypt change its point of view? In the end, we are talking about the scope of imagination.” His implication: none of his successors have had grand visions for the country. Who is the right person to lead the ministry? “I want someone who knows heritage, who knows fine art, who knows music, who knows literature, who knows theater. This makes you shine at life. Does that person exist? There is a chance that there is such a person. But he must be cultivated. Right now I will tell you that there are youths who are 30 years old or so, who are approaching this,” he said.

In March 2011, the Ministry of Culture’s monthly periodical The New Culture printed a special edition commemorating the revolution, headlined “The People Wanted Life,” riffing off the chant The People Want the Downfall of the Regime. On the cover, multitudes of protesters wave flags. Inside are 128 pages of articles, photos and poems describing the 18-Day revolt in Tahrir Square. On one page, there is a placard with President Mubarak and Culture Ministry Hosny’s faces crossed out. What role would the ministry play now that the despot had fallen?

The 2011 revolution brought political art to a vanguard position at the grassroots level and in the global art market. In Tahrir Square, impromptu installations and tent museums served as a corrective to the top-down art of the Mubarak years. Graffiti transformed the city’s most contested spaces into open-air galleries of dissent. Art was everywhere, yet talk of dismantling the ministry was quickly dismissed. Artists still needed the support of the ministry.[21]

Gaber Asfour, a literary critic who served as Minister of Culture during Mubarak’s twilight in January 2011 as well as another stint in 2014, has described the ministry as a “flabby administrative structure” that is “tied down by fossilised laws.”[22] Four ministers served short tenures in 2011 alone. Is the ministry simply ungovernable? Or are Egypt’s intellectuals too pesky and paltry a bunch to be managed under an antiquated socialist umbrella? These questions go to the heart of what role culture could play given Egypt’s post-colonial and post-revolutionary circumstances.

I requested interviews with the Minister of Culture and the head of the ministry’s Fine Arts Sector without reply. Surprisingly, for a ministry with tens of thousands of employees, the phone numbers listed on their website elicited no answer. To get an insider’s view, I met with Mohammad Talaat, a programmer for the ministry, whose most recent position was director of the Palace of Fine Arts in the Cairo Opera House complex. In 2011, he founded the private Misr Art Gallery and this year served as curator of the ministry’s annual General Exhibition.

Talaat, wearing thick plastic glasses and distressed jeans, described unfolding crises in the ministry. Speaking in Arabic and often raising his voice to make a point, he censured the jury charged with selecting artists for the Venice Biennale’s Egypt Pavilion as ignorant about art history. He complained about art forgery and nepotism. The state “is immersed in corruption and is not fulfilling its duty of stopping the forgery market,” said Talaat. “With everything, there is corruption. Ignorance. Corruption is emerging from the [special] interest relationships and networks.” Corruption in the Ministry of Culture “is very big,” he said. But none of these questionable activities are likely to be addressed. With terrorism rising and the economy tanking, “Culture is number one-hundred on the state’s agenda,” said Talaat.

He noted that the country’s leading Islamic institution, Al-Azhar, “involves itself in everything,” serving as the religious authority on art and culture. “Do we want Al-Azhar’s culture!?” he asked. There has always been a tension between the secular culture of Egypt’s intellectual elite and religion, which came to a head nearly a year into the presidency of Mohammed Morsi.

Intellectuals accused Morsi of highjacking the Ministry of Culture when he appointed an Islamist apparatchik to the top posting. In early June 2012, prominent intellectuals staged a month-long sit-in at ministry’s headquarters. That demonstration—narrowly protesting the firing of a number of qualified officials and replacing them with Brotherhood political operatives—was a precursor to the national revolt later that month. When the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces ousted Morsi in early July, many of the intellectuals stood behind General Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi. Even the harshest critics of Mubarak’s regime supported Sisi. For the most part, opposition voices were drowned out in a sea of enthusiasm for Egypt’s new Nasser.

The questions surrounding the Ministry of Culture’s activities since Sisi’s takeover have escalated of late, mostly focusing on cosmetic or operational issues rather than the big picture of Egyptian art and culture. If artists are indeed the conscience of the nation, as Sisi said in his 2014 campaign, then what role can intellectuals play now?

Culture in the Face of Terror

Before being appointed as Minister of Culture in March 2015, no one had heard of Abdel Wahed El-Nabawi. As minister, he has exemplified the shortcomings of the state’s cultural activities. Nabawi, with short hair and a dark suit, is a bureaucrat, not an intellectual. Since 2010, he served as the head of the National Library and Archives, where he rallied against the unauthorized disposal of official documents.[23] He spearheaded efforts to digitize 2 million documents and cull metadata from many millions more.[24] He was among the ministry officials who were dismissed during Morsi’s tenure and was reinstated after Morsi’s overthrow.

Nabawi is also a professor of history at Al-Azhar University, the preeminent Islamic institution in the Sunni world. Detractors gossip that the Sheikh of Al-Azhar himself advocated for his appointment to the post.[25] One recent report cited fears of the prospective “religionisation of culture,” given Nabawi’s ties with Al-Azhar and close coordination with the Ministry of Religious Affairs.[26] Nabawi maintains that he has no personal relationship with the top cleric, yet has felt the need to clarify, “Not everyone in Al-Azhar is Brotherhood.”[27]

In an interview with Ahram Weekly, the state newspaper’s English edition, he sought to dispel such rumors and bolster his credentials: “I am not just an archivist, as some are trying to suggest… I am a cultured person who enjoys good relations with many intellectuals and with the ministry’s officials.”[28] Secular intellectuals found the Minister’s closeness with the religious leadership to be unsettling.[29]

Nabawi’s approach to the creative elite mirrors Sisi’s comments on the campaign trail. In March, shortly after taking office, Nabawi spoke at Arab Poetry Day. “The creative people, intellectuals and poets, from all nations and in all languages, should spearhead the combat against terrorists who pose a threat to our existence,” he said.[30] According to critics, no new programming followed. His signature initiative, Summer of Our Children, was described to me as a continuation of previous ministry activities.

Controversy arose during an unarranged visit to the Mahmoud Said Museum in Alexandria. Nabawi told curator Azza Abdul Moneim, “If you have any problem with government centralism, I have a problem with fat employees [like you].”[31] The story went viral. Cairo tabloids covered the intricacies of the exchange, as the ministry’s spokesperson issued a statement saying the comments were taken out of context. To clear the air, Prime Minister Ibrahim Mehleb personally called the curator to ask her to forgive Nabawi.[32]

In June, Nabawi launched the “Culture in the Face of Terror” initiative in response to the assassination of General Prosecutor Hisham Barakat. Though 120 intellectuals, thinkers, and university professors are apparently signed on to the initiative, the programming still lacks in details. “Just talk,” said poet Zein Abdein Fouad in criticizing Nabawai’s initiative.[33] So far, the ministry organized an operetta against terror in Alexandria (contributing musicians received about US$255 each), gave gold medals to event participants, and co-hosted a Writer’s Union seminar. For all his efforts, there are no innovative approaches here, just inertia.

It is worth emphasizing that, in the 1950s, Nasser got top artists and thinkers on board as he revamped the country. The literary luminary Taha Hussein served as Minister of Education and revolutionized the ethos of the Egyptian schools. Nasser would frequently broadcast his radio addresses after the beloved pop singer Oum Kolsoum’s live concerts. Under Nasser, the state sought out the best cultural figures and took advantage of their cachet. Under Sisi, the state is alienating leading intellectuals over minor policies.

In July, Nabawi fired two old hands, the head of the National Book Organization and the secretary general of the Supreme Organization of Culture. Nabawi said he was “pumping new blood” into the ministry. The grievances swelled.

Mohamed Abla is a prolific painter who has exhibited two solo exhibitions in the past three months. He is among the elite group of intellectuals that has met with Nabawi to complain about the ministry’s trajectory. Denouncing Nabawi’s initiatives as “failed,” Abla made headlines in August. “The Egyptian Ministry of Culture… must be aware that Egypt is now at war with terrorism, so it is necessary to have a clear laid-out plan, not just statements or changes in administrative posts,” he told the local news outlet Veto Gate. “The Ministry of Culture has failed in the face of terrorism, as it alienates youth…” and in turn pushes youth toward terrorist organizations, according to Abla.[34] The painter wants the Ministry to live up to its role by creating innovative initiatives that raise the spirits of young people.

Incensed intellectuals have threatened to hold a sit-in before Nabawi’s offices, much like they did under Morsi. The crisis between the intellectuals and ministry deepened, and in the last week of July Prime Minister Mehleb met with Abla and others.

Even after meeting the Prime Minister, the intellectuals remain dissatisfied. Their concerns, however, remain tied to the Ministry of Culture’s operations and seem wholly disconnected from the circumstances facing artists and writers in Egypt. This coterie of intellectuals, for example, has not protested the new counter-terrorism law, which President Sisi passed one August night. The legislation, which Human Rights Watch sees as a “permanent state of emergency as the law of the land,” imposes the death penalty on many violations related to terrorism.[35] Gravely, the definition of terrorism is so vague that nonviolent dissent might fall into the category of illicit speech. Instead of griping about the authoritarian state of affairs in Egypt, the intellectuals who have the state’s ear are using their perches to address the smallest of problems, like the Minister of Culture’s ignorance. Egypt’s leading intellectuals are providing the perfect distraction.

With competing opinion articles in the local press about cultural affairs, top writers are still batting off arguments against the “Culture in the Face of Terror” initiative. “The minister… reflects the direction of the new state that wants to be relieved of the headaches and hullaballoo caused by the intellectuals,” wrote Mahmoud El-Wardany in the literary weekly Akhbar Al-Adb. The real nuisance, however, is figuring out how culture can endure in the face of terror, a subject that neither the state nor the intellectuals have addressed.

Let us now return to Siwi’s column in Al-Ahram, which reacted to this tiff between the intellectuals and the state. For Siwi, the personage of the minister himself is irrelevant. “Is he not a rural, academic, conservative governor with limited capacities, just like any other official?” he wrote.[36] Instead, Siwi has focused on the lack of political expression in the country. Siwi told me, “Everything is pharaonic right now.”

The Legitimate Intellectual

In Al-Ahram, Siwi lucidly described the state’s interest in culture as purely instrumental:

The state is the state—it has inured us to [that role]. It alone defines its shape and the shape of its opponents, too, inside the scene [the state] has conditioned us to—like the photo of a big family assembled. [The state] determines the position of all the elements: The Sheikh of Al-Azhar here and the head of the church there; then the great leaders of the military and the police, the ministers, the role models of the judiciary, and the big men of the old regime. Then some businessmen and public figures. It doesn’t mind some young faces or women or rural folk or Bedouins, and maybe someone with special needs, in order for the picture to be completed. It’s the image of a seemingly coherent entity. The state determines the elements precisely but it is not satisfied with it. So [the state] similarly selects its opponents: this author or that artist, this actor or that director, etc.[37]

Of note is that the state chooses its opponents just as it chooses its supporters (every hero needs a nemesis). For Siwi, what the intellectuals are arguing over is where they fit into this big family photo, which itself is a construction of the state. Seeing the forest for the trees, the intellectuals are jockeying for more recognition from the state without interrogating the state’s repressive policies.

Siwi’s conclusion is so damning that it is worth reading in full, as it is a meditation on how the state has sucked politics from the country and forced them into daily life.

What is always absent is politics. We have no politics and this is why it is difficult to talk about freedom. Yet freedom is the essence of political action; it is necessary to advance cultural or creative production for any human society. It seems that the intellectuals have voluntarily waived all demands [for freedom] taking into consideration these circumstances, as I understand it. The way authoritarian regimes abrogate politics is by politicizing life entirely. Thus, we have a fully politicized reality—which has nothing to do with the make-up or rotation of authority, but rather mobilizing the public, whereby political speech replaces never-ending propaganda, which citizens breath every morning and evening. Hence, culture, action, and everyday life itself become politicized. Every entity, every situation, and every idea put forward is either pro or con—as Dubya boldly summarized the issue, “You’re either with us or against us.” It is not possible to separate the state’s performance in the cultural field from its general approach and its taking of sides.[38]

The painter concluded his column by calling on his colleagues to fight for basic rights rather than minor adjustments in ministry policy. “Finally, we all must remember that the defense of creative freedom now—after the regime chose for us this minister—has become a test for the entire coterie of intellectuals,” wrote Siwi.[39]

Siwi and I sat for nearly three hours discussing the history of the Ministry of Culture, definitions of the intellectual, the generation gap that has emerged since the revolution, and the role of politics and art. As I thanked him for his generosity, Siwi was humble. He inquired about my research and writing, and handed me a volume of Giuseppe Ungaretti’s poetry he had translated from Italian to Arabic. Then he asked me, “What didn’t you like about my article?”

Unlike Siwi’s humble request, the spirit of debate and discussion was absent three weeks later, when Prime Minister Mehleb submitted his entire cabinet’s resignation to President Sisi, on a Saturday. No uproar followed because, as Siwi noted in his article, there is no politics. No reason was given publicly for the cabinet’s dissolution, though it seemed related to the public perception of corruption. Earlier in the week, the Minister of Agriculture had been arrested for receiving bribes. Oil Minister Sherif Ismail is now tasked with forming a new cabinet in the next two weeks, and it is rumored that Minister of Culture Nabawi will not retain his post.

Nabawi told the privately owned newspaper Al-Masry Al-Youm a week prior that he was “eager to communicate with all intellectuals in Egypt.” He bluntly acknowledged the storm gathering against him and sought to use it to his advantage. “There are those among the intellectuals who stand with me and others do not agree with me. This is under the protection of the freedom of opinions and expression. It is the right of everyone to express and defend their ideas, even if they disagree with a minister or an official,” said Nabawi.[40] Indeed there is freedom of speech when it comes to criticizing the Ministry of Culture, but one scarcely finds articles critical of the government’s security or economic policies in the mainstream media.

Intellectuals continue to lambast the Ministry rather than consider their own responsibilities. In mid-September, poet Girgis Shoukry published a full-page essay disparaging Nabawi in the literary weekly Akhbar Al-Adb. Shoukry compared Nabawi’s initiatives for the Ministry’s cultural palaces to a popular potato chip brand: “Culture is becoming like a bag of Chipsy, nothing but artificial flavors and additives, harmful to intellectuals and non-intellectuals.”[41] That may indeed be the case. The Ministry of Culture is hawking products that have passed their sell-by date. But if Egyptian culture feels artificial, it is tied to a larger crisis of expression, including the stifling of artistic interventions that emerged from the 2011 uprising. A state-centered culture cannot sweeten the bad taste.

[1] Throughout this Newsletter, the word “intellectual” neither refers to the cerebral nature of an individual nor the so-called “public intellectual,” though sometimes those definitions will also fit. Rather, in the Egyptian context, the word “intellectual” pertains to the assortment of creative producers of national renown, who dabble in political activities and engage in varied relations with the state and, in particular, the Ministry of Culture.

[2] “State of Optimism Among Intellectuals after the Opening of the New Suez Canal,” Al-Bawaba News, 10 August 2015. Available at: http://www.albawabhnews.com/1438480

[3] My translation of the Arabic article used throughout this Newsletter. Adel El Siwi. “The Legitimate Intellectual,” Al-Ahram, 8 August 2015. Available at: http://www.ahram.org.eg/WriterArticles/2236/2015/0.aspx

[4] Ibid.

[5] Dandawry Hawary. “Sisi during a Meeting with Men of Letters and Writers: Intellectuals Constitute the Conscience and Consciousness of Egypt…” Youm7, 12 May 2014. Available at: http://www.youm7.com/story/2014/5/12/السيسى_خلال_لقائه_بالأدباء_والكتّاب__المفكرون_يشكلون_الضمير_/1661454#.Ve8PpiQxE0p

[6] Jonathan Guyer. “Picturing Egypt’s Next President.” The New Yorker, 22 May 2014. Available at: http://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/picturing-egypts-next-president

[7] Scholar Elliott Colla notes, “In the context of lead-up to the Rabaa massacres, it is difficult to read the document as anything but a permission slip to commit atrocities against Islamists.” See: Elliott Colla. “Revolution on Ice,” Jadaliyya, 6 January 2014. Available at: http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/15874/revolution-on-ice

[8] Kim Gamel. “Rights Activists Split Over Egyptian Politics,” AP/ Times of Israel. 29 September 2013. http://www.timesofisrael.com/rights-advocates-split-over-egyptian-politics/

[9] Writer Youssef Al-Qaid’s comments to the television network Al-Hayat, posted online at: “Video: [What] They Said About Sisi’s Meeting with Intellectuals: A Meeting Without Red Lines,” Dot Misr, 21 December 2014. Available at:

http://www.dotmsr.com/details/فيديو-قالوا-عن-لقاء-السيسي-بالمثقفين-لقاء-بلا-خطوط-حمراء

[10] Ursula Lindsey. “Egyptian Intellectuals, Revolution, and the State,” The Arabist, 9 January 2014. http://arabist.net/blog/2014/1/7/revolution-on-ice

[11] Guirgis Milad. “Sisi: Regular Egyptians are More Important to Me Than Intellectuals,” Al-Wafd. 6 August 2015. Available at:

http://alwafd.org/ميـديا/889581-السيسي-المصريون-العاديون-أهم-عندي-من-المثقفين

[12] See for instance: Sarah Carr. “President Sisi’s Canal Extravaganza,” Foreign Policy, 7 August 2015. Available at: http://foreignpolicy.com/2015/08/07/sisi-dredges-the-depth-egypt-suez-canal-boondoggle/

[13] Cairo University Professor Randa Abou Bakr recently delivered a lecture on this topic at the University of Sydney: “The Intellectual and the Revolution: On Egypt’s New Strand of Intellectuals.” I hope to obtain a copy of her paper and explore this new “strand of intellectuals” in a future Newsletter.

[14] Jessica Winegar. Creative Reckonings: The Politics of Art and Culture in Contemporary Egypt. Stanford University Press, 2006. Page 47.

[15] Winegar and Sonali Pahwa write, “The major goals at the time [of Nasser] remain central to the Ministry’s mission today: to define the nation and national identity; to protect cultural patrimony; and to uplift the so-called masses by exposing them to the arts.” See: Sonali Pahwa and Jessica Winegar. “Culture, State, Revolution.” Middle East Report, Summer 2012. Available at: http://www.merip.org/mer/mer263/culture-state-revolution

[16] Robyn Creswell. “Egypt: The Cultural Revolution,” New York Times, 20 February 2011. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/20/books/review/Creswell-t.html

[17] Winegar, 2006. Page 150.

[18] Marcia Lynx Qualey. “Who’s Afraid of Farouk Hosni?” Arab Literature (in English), 13 September 2010. Available at: http://arablit.org/2010/09/13/whos-afraid-of-farouk-hosni/

[19] Nizar Manek and Jeremy Hodge. “Sisi’s Secret Gardens,” London Review of Books Blog, 20 July 2015. Available at: http://www.lrb.co.uk/blog/2015/07/20/nizar-manek/sisis-secret-gardens/

[20] Ursula Lindsey. “Bad Minister,” The Arabist, 10 July 2009. Available at: http://arabist.net/blog/2009/6/10/the-bad-minister.html

[21] For further discussion, see: Pahwa et al, 2012.

[22] Nervine El-Aref. “Renewing Discourse,” Ahram Weekly, 25 February 2015. Available at: http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/News/10567/23/Renewing-discourse.aspx

[23]Archives, of course, are political in nature, especially in how they are managed. Egypt’s National Archives are renowned for their inaccessibility and poor upkeep, though Egyptian intellectuals have not rallied around this cause. As historian Khaled Fahmy notes: “The National Archives holds approximately one hundred million documents, while it is visited by less than 10 researchers daily. Where are the intellectuals? Have they not been concerned with this situation? A visit to the reading room at the National Library is a true insult to any individual…” Khaled Fahmy, “Ministry of Culture or Ministry of Intellectuals?” Ahram Online, 8 June 2013. Available at: http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContentP/4/73416/Opinion/Ministry-of-culture-or-ministry-of-intellectuals.aspx

[24] Mohammed Saad. “Head of Egypt National Archives: State institutions illegally dispose of documents,” Ahram Online, 29 October 2013. Available at: http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/18/0/84935/Books/Head-of-Egypt-National-Archives-State-institutions.aspx

[25] Nervine El-Aref. “Eye on the Future,” Ahram Weekly, 16 April 2015. Available at: http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/News/11025/17/Eye-on-the-future.aspx

[26] Mohammed Saad. “Minister of Culture Stirs Fears of ‘Religionisation of Culture.’” Ahram Online, 29 July 2015. Available at: http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContentP/18/136376/Books/Minister-of-culture-stirs-fears-of-religionisation.aspx

[27] Saher El-Miligi. “Abdel Wahed El-Nabawi: The Cultural Dispute is evidence of ‘intellectual diversity’… And Not Everyone at Al-Azhar is ‘Brotherhood.’” Al-Masry Al-Youm, 4 September 2015. Available at http://www.almasryalyoum.com/news/details/804534

[28] Ibid.

[29] When I spoke with Nervine El-Aref, the assistant managing editor of Al-Ahram weekly who conducted the aforementioned interview, she told me that Nabawi “never ever answered my questions.”

[30] “Egypt’s Minister of Culture Seeks Intellectuals’ Support in Anti-Terror Fight,” International Islamic News Agency, 22 March 2015. Available at: http://iinanews.org/page/public/news_details.aspx?id=81454&NL=True

[31] Nada Deyaa. “Minister of Culture Does Not Approve of ‘Fat Employees,’” Daily News Egypt, 15 April 2015. Available at: http://www.dailynewsegypt.com/2015/04/15/minister-of-culture-does-not-approve-of-fat-employees/

[32] Nada Deyaa. “Mehleb Apologises to Museum Curator Mocked by Culture Minister,” Daily News Egypt, 21 April 2015. Available at: https://www.dailynewsegypt.com/2015/04/21/mehleb-apologises-to-museum-curator-mocked-by-culture-minister/

[33] Menna Allah-Abiyad. “Creators: Culture in the Face of Terror Initiative has Failed, is Limited, and Suffers Mismanagement,” Ahram Gate, 21 July 2015. Available at: http://gate.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/25/111/704709/المقهى-الثقافى/متابعات/مبدعون-مبادرة-الثقافة-في-مواجهة-الإرهاب-فاشلة-ومحد.aspx

[34] Merna Abu-Nady. “Abla: Them Ministry of Culture’s Laws and Regulations Encourage Corruption,” Veto Gate, 27 July 2015. Available at: http://www.vetogate.com/1741184

[35] “Egypt: Counterterrorism Law Erodes Basic Rights,” Human Rights Watch, 19 August 2015. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2015/08/19/egypt-counterterrorism-law-erodes-basic-rights?mc_cid=dd63880f40&mc_eid=c81700eaa3

[36] Siwi, 2015.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Siwi, 2015.

[39] Ibid.

[40] El-Miligi, 2015.

[41] Girgis Shoukry. “Cultural Palaces to “Flavor” Culture!” Akhbar Al-Adb, 13 September 2015. Available at: http://www.dar.akhbarelyom.com/issuse/detailze.asp?mag=a&field=news&id=10456