AMSTERDAM — I first met Has Cornelissen on a beautiful sunny day at Sarphatipark park in the hip De Pijp neighborhood. He is a veteran drug legalization advocate with a ready smile and a youthful appetite for life. In the 1990s, he organized street demonstrations for the regulation of recreational drug use. Last year, he helped found the Netherlands’ own Law Enforcement Action Partnership (LEAP). First conceived in the United States, LEAP brings together current and former police officers to push for policies that treat problematic substance use as a public health rather than law enforcement issue. The 6’4” devoted father of two has been my gracious and indispensable guide on my journey through his country.

Within a few steps of entering the verdant park, we ducked behind some undergrowth, leaving the gravel path for a hidden hangout for local hard drug users littered with trash and soiled tissues. No one home. Within 30 seconds, we were back among families and chic young people sprawled across perfectly kept grass catching the sun.

I came to the Netherlands because the US model for responding to substance use and abuse is resulting in the death of one American every five minutes. That’s more sons, daughters, fathers and mothers who die annually than from firearms and motor vehicle crashes combined. And for every fatal overdose, there are 15 non-fatal overdoses that cause physical and mental trauma. They not only affect the victims but also tear at the fabric of our families, communities and society.

It does not have to be this way. The Dutch overdose rate is 19 times lower than in the United States. The availability of intoxicating substances is not the issue: the Netherlands is flooded with them. It is Europe’s largest entry point for heroin and cocaine, and the continent’s largest producer and exporter of beer, amphetamines and ecstasy. More cocaine is confiscated at the port of Rotterdam than all US ports of entry combined. Still, the prevalence of cocaine use was lower in the Netherlands than in America as of 2019. Moreover, the Netherlands is routinely ranked one of the happiest, safest, most productive and child-friendly places in the world. How is that possible?

While problematic use of drugs and alcohol is prevalent across socio-economic classes, the most visible kind of addiction is the one most Americans see going to work or the grocery store every day. Destitute panhandlers at busy intersections and collapsed figures sleeping on cardboard boxes under unsuspecting stoops.

But substance use does not necessarily lead to homelessness. According to the US National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 46.8 million (16.7 percent) of Americans struggle with a substance use disorder, yet the Department of Housing and Urban Development estimates that only 653,100 (0.2 percent) of Americans experience homelessness on any given night. Rises in homelessness in an area are driven primarily by housing costs affecting poorer communities, the Pew Research Center found.

In the Netherlands, the number of people experiencing homelessness almost doubled to 0.17 percent of the population over the past 15 years. Not too dissimilar to the United States. Yet in a month of living in Amsterdam, where rents have seen recent double-digit increases year-over-year, I’ve counted the number of homeless people I’ve seen on one hand.

How does the Dutch public health care approach effectively prevent individuals with problematic substance use at-risk of homelessness from ending up on the street? Ruud Rutten, chairman of the Tactus addiction rehab center in eastern Netherlands estimates that while 90 percent to 95 percent of people with substance addiction can recover through a combination of outpatient individual or group cognitive behavioral therapy, medication-assisted treatment, and steady employment, there will always a be few whose chronic substance use requires full-time social subsidization.

In search of the Dutch solution to this small but care-intensive group, I accompanied Has to a one-story brick building housing chronic users an hour-and-a-half drive south of the capital near the Belgian border. Operated by the Dutch Salvation Army, the facility is tucked away on a leafy campus that includes a rehab center situated a short bike ride away from the town of Bergen op Zoom.

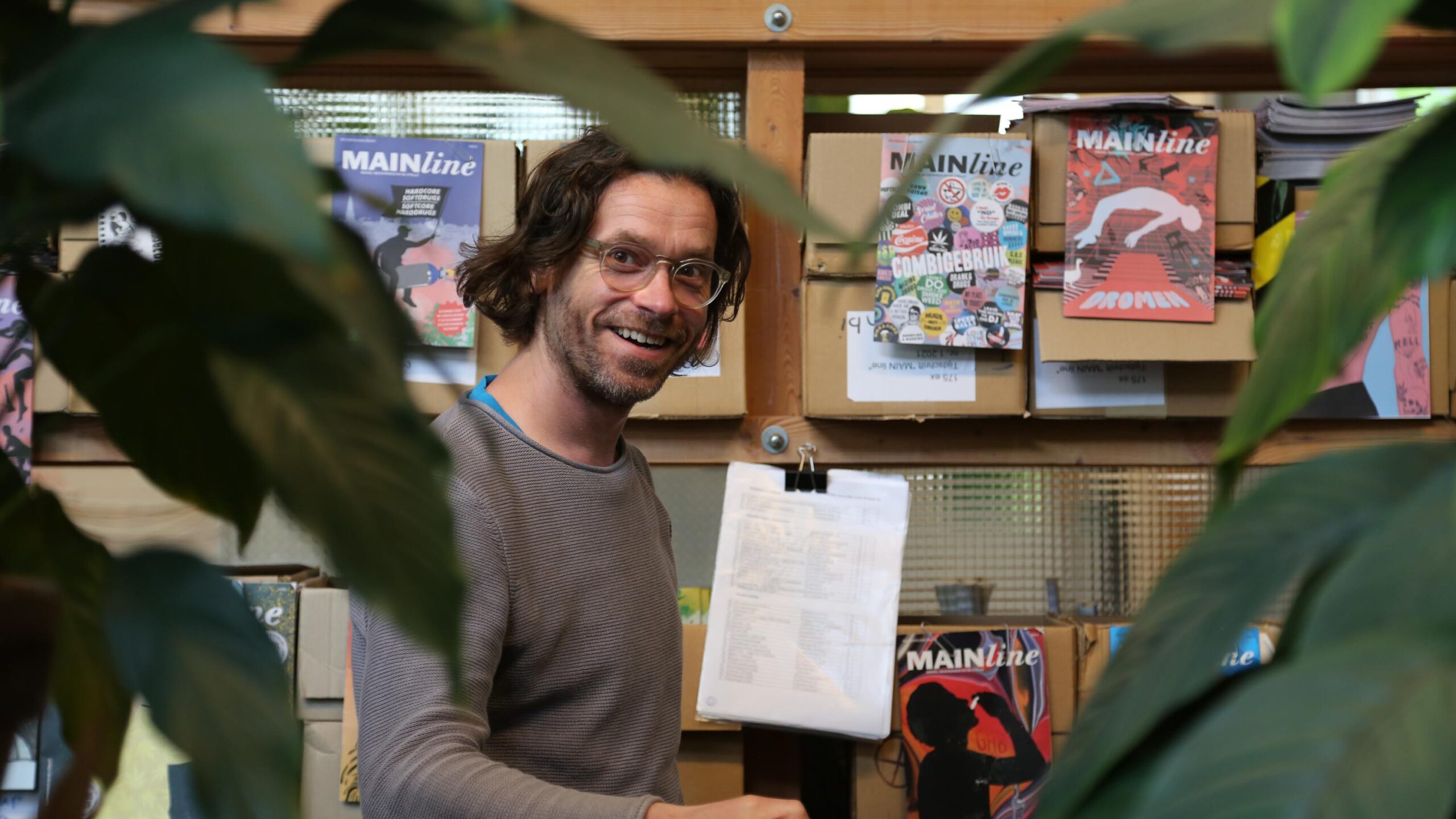

Staff appeared relaxed and the halls were clean if somewhat bare. On the wall hung a “drugs overview” of 13 substances including alcohol, cocaine, heroin and MDMA together with their modes of use, effects and risks. Has and I installed ourselves in the communal kitchen with brochures for Mainline, a leading harm reduction and drug monitoring non-profit based in Amsterdam for which Has works.

It was lunchtime and residents ranging from their 30s to 60s came through to make sandwiches. Although addiction had hardened their features, residents appeared recently showered, well dressed and amiable. As he cleaned their drug pipes, Has questioned curious residents about the quality of the street supply. While fentanyl has not yet been seen in the Netherlands, such fieldwork monitoring helps ensure the use of dangerous new drugs is quickly addressed if it appears.

Alcohol and cocaine seem to be the primary substances of choice with a few new synthetic stimulant “designer drugs” rounding out the supply. Residents are allowed to use alcohol and drugs while they are provided housing at facilities like this one across the Netherlands. It is a last resort for those whose addictions have taken everything else from them.

The two dozen residents get a private room with a bathroom. They share kitchen, living room and dining room spaces. During the day, they are free to bike into town and otherwise go about their business as they see fit. Staff teach residents life skills such as proper sleep schedules, cooking and cleaning. There is no pressure to stop using, but if they ask, residents are quickly referred to rehab, employment and other services.

The back-of-the-napkin explanation for how such facilities are financed includes that each Dutch citizen who breaches the poverty line receives around 900 euros per month from the state. Of that, 150 euros goes to paying for mandatory private health insurance coverage, 350 euros to the housing non-profit, and the rest can be spent at will provided recipients have no outstanding debts. Local and national government funds also subsidize housing non-profits to ensure their financial viability.

This facility is a prime example of the effectiveness of the so-called housing-first model. Initially pioneered in New York City in the 1990s by a doctor named Sam Tsemberis, it contends that giving people experiencing chronic homelessness long-term stable housing without preconditions and with voluntary support services is key to achieving improved lives. While the model has faced pushback in the US, it has been fully embraced in the Netherlands.

In the United States, poor and middle-class people suffering from problematic substance use are essentially left to hit “rock bottom,” forced onto the street or into jail with limited viable paths to sustainable recovery. Homelessness negatively exacerbates mental and physical health while undermining the public social fabric.

In the Dutch model, by contrast, residents of housing-first models maintain their individual freedoms and dignity, the public sphere preserves its order and peacefulness, and taxpayers benefit from the lower administrative burdens required to operate the scheme than the cost of emergency shelters, recurring incarceration and emergency hospital care seen in America.

As I was processing the implications of what I’d witnessed in Bergen op Zoom, Has brought me to another type of center in the east of the country. We drove through a gated entrance with no outward signage into a small courtyard flanked by two elegant buildings. The complex is in an affluent neighborhood near the train station in the city of Enschede. The city sits on the border with Germany an hour-and-a-half by car from Amsterdam with a population of about 160,000.

The first building we entered was three stories high, homey, full of handmade art, and prompted the feeling of being in a day care. It turned out that’s exactly what it is, but instead of children, it caters to problematic substance users who would otherwise loiter on the streets and public parks.

In the backyard garden, a staff member led an arts and craft workshop. Inside, a group of mostly men were helping with chores or talking among themselves or with staff. Those participating in activities get three free meals a day, those who don’t must pay a token one euro per meal.

As Has questioned users and staff about the local street-drug market, I found myself talking in conversational English with one of the local drug dealers. In his late 50s, he was cocaine skinny with a five o’clock shadow, sporting jeans and a weather-beaten suit jacket. He regaled me with stories of his youthful crime escapades involving stolen cars and moonlit rendezvous. Now, he said, he fills his times with fanciful dreams of moving someplace warm and dry. Before long another individual joined us, and together they walked away toward a less observable part of the garden. The atmosphere was relaxed. I enjoyed a cup of tea.

Once Has felt he got the information he needed, we walked across the courtyard to the second building. Two men disassembled old bikes as we passed. The one-story structure felt more clinical. As I took a seat with Has to chat with a staff member, two gentlemen in their 60s smiled brightly as they smoked cocaine from customized pipes in an adjacent room separated from us by a large glass window. One of them gave us an enthusiastic thumbs up that we heartily returned.

The building houses three separate safe consumption rooms: one for smoking, another for injecting and the third for drinking alcohol. The injection room was empty except for two metal chairs in front of a spare metal table attached to the wall. Thanks to a massive public health campaign started in the 1970s and ’80s, very few people inject drugs in the Netherlands. Heroin is primarily smoked. However, newly arrived migrants from eastern Europe are slowly bringing with them the intravenous drug habits more prevalent in their countries.

In the room where we were all sitting, the staff member supervised the entire process through fishbowl windows with views on the outdoor entrance and two consumption rooms. He checks people in, writes down what drugs they are using and how much, and monitors usage in case something goes wrong. Overdoses are rare because the heroin is pure with few adulterants. To use the rooms, participants must be registered with the facility, a relatively easy process.

The drinking room is through a separate outdoor entrance. Unlike the medical atmosphere of the injection and smoking rooms, it feels more like a cross between a bar and a living room. Sports team merch hangs on the walls, there’s a comfy-looking couch and American soft rock played in the background.

Sitting at a long dining room table, half a dozen men enjoyed tallboys of a local brew, supervised by a staff member. If participants help with chores around the facility, they are allowed a few beers on top of their hot meals. There is some crossover between those who use the drinking and smoking rooms, but it was unclear to what extent. Has cracked some jokes in Dutch before we made our way to the final section of the facility.

The building’s third segment holds methadone and heroin clinics. Unlike in the US, methadone is routinely prescribed as take-home medication to chronic patients for multiple weeks at a time. But the heroin clinic’s rules are much stricter. Patients must have failed methadone treatment numerous times and meet other stringent requirements. Mental health counseling is required as part of the program, and patients must come daily to the clinic for their doses. That explains why some continue to utilize the smoke room using street heroin.

The integrated addiction day care and treatment center is open every day from 9:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. All the men and women taking part have some form of housing when the center is closed not provided by the organization. By giving a place for the chronically addicted to go during the day with warm meals and proper treatment, the center effectively promotes individual dignity and public safety.

On returning to Amsterdam, I contemplated why the Netherlands of all countries had come to pioneer the implementation of an integrated public health approach to substance use. Has summed up the prevailing attitude: “People have a right to make decisions about their own lives, and the government has a responsibility to ensure that they have accurate information to make the best decisions for themselves.”

The Dutch believe citizens should be able to love whom they want, use the drugs they want, be assisted in suicide, engage in prostitution, gamble and otherwise live private lives without interference from the government. They are also ruthless about their desire to bring a sense of peace to the public sphere. The streets are clean of trash, there are almost no wandering homeless people and lawns are always mowed. Unlike in the United States, where public order is primarily associated with law enforcement action, in the Netherlands, it is achieved through robust social housing, mandatory private health care and modest welfare programs. Law enforcement is utilized as a last resort.

To harmonize those sometimes competing forces, the Dutch “polder model” of governance prioritizes consensus-building among stakeholders with a focus on evidence-based practices and long-term thinking. It stems from the country’s very fight for existence.

Over 10 percent of the Netherlands is reclaimed land, 26 percent of the country is under sea-level, and 55 percent is flood prone. Since its founding, Dutch communities have had to painstakingly work together to build, fortify and maintain a world-renown system of dykes to ensure their country thrives. All residents are expected to do their part to build and sustain the common prosperity the Dutch enjoy.

These three dominant cultural foundations of respect for individual freedom, public order and the polder model of government can be recognized by any tourist familiar with Amsterdam’s bustling streets, where bikes, electric bikes, cargo bikes, trams, mopeds, motorcycles, cars, trucks and pedestrians fight for space. To bring order to the chaos, the authorities have clearly separated bike lanes, sidewalks and streets with stop/go lights for each form of transportation. The clear guardrails and their strict enforcement reduce potential conflicts to a minimum while enabling everyone to travel in the way that best suits each.

It is hard to overstate how peaceful this bustling city of 822,000 inhabitants appears after coming from Washington D.C. with its 671,000 inhabitants. Living in the US capital’s center in the affluent Logan Circle neighborhood, I could on any given day be greeted outside with police lights, ambulance sirens, panhandlers, gun shots and an ever-present risk of aggression. In the months leading to my departure, two friends were robbed at gunpoint. After a month in Amsterdam, the greatest disturbance I expect to hear is a bike bell. Thanks to their integrated public health approach, the Dutch go about their day nonchalantly without fear of the unexpected or the unpleasant.

By the time you finish reading this dispatch, 30 Americans will have overdosed, two of them will be dead. Fathers leave behind grieving children and wives. Sons and daughters leave distraught sisters and brothers. While economists estimate the public cost of the US opioid epidemic at $1.5 trillion a year, its real toll is far greater. The empty chair at Thanksgiving dinner, the uneaten burger at the July 4th cookout, the guilt we suppress hurriedly walking by another homeless encampment.

It is my hope that investigating public health approaches and their cultural underpinnings in the Netherlands, Portugal and Brazil over the next two years will inspire fellow Americans to implement policies that promote individual dignity, public peace and most of all, compassion.

Top photo: A local marching band prepares to perform for the Tulip Flower Parade outside the town of Lisse