Andrew Tabler’s ICWA fellowship in Bashar al-Assad’s Syria (2005-2007) focused on the country’s reform and Lebanon policy, leading to his next role as a consultant on US-Syria relations for the International Crisis Group. As a fellow, he achieved unparalleled access to Syria’s elites. He also co-founded its first private English-language magazine and, during his 14 years in the region, interviewed Shimon Peres, Yasser Arafat, Rafiq Hariri and other leaders.

Andrew Tabler’s ICWA fellowship in Bashar al-Assad’s Syria (2005-2007) focused on the country’s reform and Lebanon policy, leading to his next role as a consultant on US-Syria relations for the International Crisis Group. As a fellow, he achieved unparalleled access to Syria’s elites. He also co-founded its first private English-language magazine and, during his 14 years in the region, interviewed Shimon Peres, Yasser Arafat, Rafiq Hariri and other leaders.

Andrew is now senior fellow at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. He has served as senior adviser to the State Department’s Special Envoy for Syria Engagement (2020-2021) and director for Syria at the National Security Council’s Middle East Affairs Directorate (2019). His writing on US foreign policy appears widely in major news outlets.

During his fellowship, Andrew explored a kaleidoscope of political activity beneath the surface of the totalitarian regime, and interviewed many of its players. In this 2006 report six years into Assad’s 24-year rule, he addresses coalitions and movements striving for democracy. Attending an opposition sit-in, he narrowly escaped being beaten.

Andrew recently said of this dispatch, written five years before the Arab Spring, “Researching that story changed my perspective completely and ultimately led me to getting kicked out of Syria a few years later.”

DAMASCUS (March 2006) — It was March 9, the 43rd anniversary of the declaration of “emergency law” in Syria. For the second year in a row, members of the Syrian Students’ National Union were busy beating up and chasing off opposition figures staging a sit-in in front of the old Ministry of Justice.

A man with grey hair broke from the crowd of demonstrators, arms waving overhead. Scores of student-union protestors were on him like a swarm of bees, shouting “traitor” while beating him with wooden sticks adorned with Syrian flags.

As I took a photo of the melee, colleagues Hugh Macleod, an eager British journalist, and Obaida Hamad, a Syrian reporter, sized up the situation, notebooks in hand. “Come on, let’s go talk to that guy!” Hugh said.

Obaida and I looked at each other. Without saying a word, we understood that the worst thing that could happen to this brave man at that moment would be for two foreigners to ask him how he felt about being abused and beaten up. We probably knew the answer anyway. “That’s the story!” Hugh shouted, eyes wide.

In an ideal sense, he was right, of course. But in a country where nationalist sentiments are high [due to US and UN pressure], it is often hard to know what to do. If the man wanted to talk to foreigners—and put his neck on the line—that was his choice. But if we approached him, it could be seen as the very treasonous activity of which he was being accused, leading to possible dire circumstances that could prevent him from enjoying the very freedom he seeks—permanently. We did not have time to mull it over, however, since the students quickly converged on another target—me.

…

Suddenly, a young man appeared wearing a white baseball cap on which was printed “I love Syria” in English. “It’s OK,” he said, smiling at me. “Please, this way.” He gave a single hand-motion that Moses might have used to part the Red Sea, and the crowd quickly obeyed. We were escorted to the side, and the mob turned its attention toward its next victim.

…

This ramshackle bunch of Marxists, Communists, Socialists, Arab Nationalists, Liberals, Islamists, Assyrians and Kurds have finally agreed on something—the Damascus Declaration for Democratic National Change. Announced on October 16, 2005, the Damascus Declaration calls for peaceful and gradual change toward a democratic regime in Syria.

With over a thousand signatures to date, the Declaration has united Syria’s domestic and exiled opposition groups for the first time in the country’s recent history.

What is behind such rare accord? Strong external pressures, growing nationalist and Islamic sentiments, and a pervasive sense that the regime is simply unable to carry out political reforms promised by President Bashar al-Assad nearly six years ago, has the opposition prescribing democracy as the cure for Syria’s ills.

While the Declaration’s leadership has its act together, they now have competition from an old adversary, former-Vice President Abdel Halim Khaddam, who formed a rival opposition front including the Muslim Brotherhood on March 17. Just who will join which group remains to be seen. Perhaps the biggest question now, however, is how Syria’s opposition can avoid becoming a casualty of the escalating cold war between Damascus and Washington that neither capital can afford to lose.

…

Both the Syrian government and Washington have responded to the Damascus Declaration selectively. The regime seems to be giving Abdel Azim [spokesperson for the National Democratic Rally and the Damascus Declaration] considerable leeway in carrying out the accord’s activities, despite the fact that the regime’s nemesis, the Muslim Brotherhood, is one of the Declaration’s primary supporters. Drafts of a new parties’ law currently making their way around Damascus indicate that the regime is not making much space for opposition parties. Parties that are “chaotic, terrorist, fascist, theocratic, religious, ethnic, sectarian, tribal, etc.” will be denied license—leaving little room for many of Syria’s opposition parties, including the Muslim Brotherhood and the Kurds, to formally join political life.

…

Making things more complicated, the Muslim Brotherhood’s [chief Ali Sadreddin al-] Bayanouni announced the formation of a “National Salvation Front,” a group of 17 exiled opposition parties that call for “democracy” to replace the regime of Bashar al-Assad. How the front’s formation will affect the Damascus Declaration—especially in light of the Muslim Brotherhood’s inclusion in both groups—remains to be seen.

“The Damascus Declaration has no value without the Muslim Brotherhood,” said Nashar [Samir Nashar, leader of the nascent Free National Party], who was arrested and then released three weeks after my interview. “They have a democratic awareness—perhaps more than the Syrian intelligentsia.”

Riad al-Turk, a member of the Syrian Democratic People’s Party, one of the five parties included in Abdel Azim’s National Democratic Rally, said in an interview with the pan-Arab daily Al-Hayat, “The basic conflict is now between external opposition representing America and the domestic opposition representing the regime. The hope is that there is a liberation front that will support a general political line calling for democratic change and preserving national independence while not falling into a severe crisis like in Iraq.”

So for the moment, as Syria’s opposition sorts things out, perhaps the best way for the US to help democracy in Syria is to leave well enough alone, but lend a helping hand at the right moment.

“We want the world to know that there is an opposition in Syria, that we have a position, and that they can help us,” Abdel Azim said after the sit-in. “But do me a favor,” he said, handing me a copy of the Declaration’s latest statement. “Remind me to get this thing translated into English.”

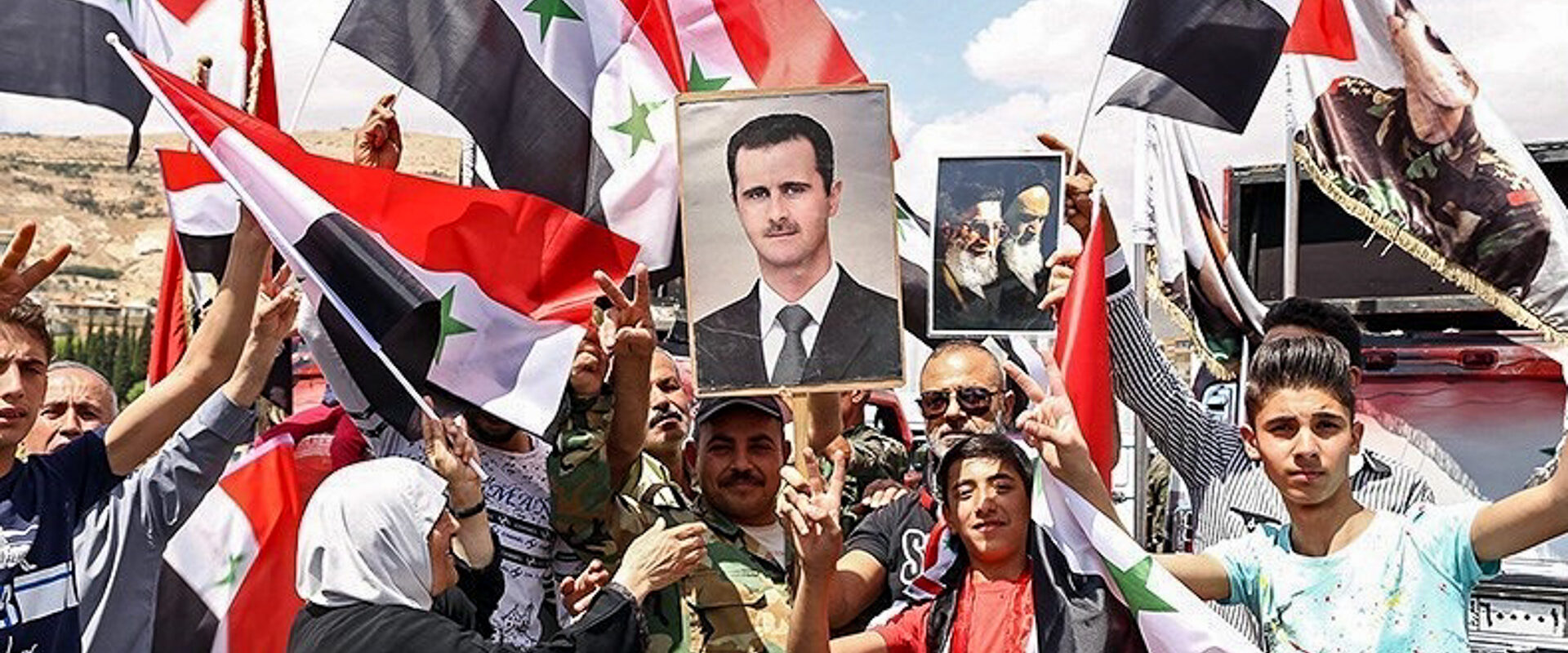

Top photo: Pro-government Syrians demonstrate in Damascus after US missile strike in 2018 (Fathi Nizam, Wikimedia Commons)