Until the summer of 2014, La Paz had lived up to its name, which means ‘the peace.’ The coastal city on the Baja peninsula seemed immune from the drug trafficking violence of the mainland, which is estimated to have claimed 120,000 lives since 2006. But on July 31st, that bloodless exemption vanished. On the side of the road leaving La Paz, an incinerated car was found with three charred bodies inside. This sickening sight, typical of ‘narco violence’, had not been a part of life in the quiet city. The reporters on the scene stood in disbelief — this just didn’t happen in La Paz.

Since that day, 120 homicides have been reported in La Paz. The previous year, there were zero.

Is it all because of a hurricane?

Mexico’s narco violence recently came into focus for me because of an unexpected link to climate change. A resident of La Paz stated matter-of-factly to a friend of mine that Hurricane Odile was the tipping point for the increase in cartel violence in La Paz. The storm created the chaos needed for a disruption in the existing organized crime in Baja California Sur, and now the region was newly plagued by the cartel’s internal war, he said. When I heard this story, I started asking around La Paz to learn more.

I moved to La Paz one year ago with funding to research vulnerability to sea level rise in Baja, and I fell in love with this desert town on an emerald sea. Despite being the second fastest growing city in Mexico, with a population of over 250,000, La Paz feels like a seaside pueblo. A crimson-and-white tile malecón, or boardwalk, stretches for over two miles on the tranquil waterfront. Fishermen, families, rollerbladers, dog walkers, skateboarders and sunbathers share this strip of coast. The people are tied to the rhythms of the desert: everyone emerges from their shady stoops throughout the city to stroll after sunset, enjoying the breeze off the water and the festive twilight scene. No railing separates those on the wide promenade from the glittering sea lapping at the sand only a few feet away. The giggles of kids fill the air. Restaurants line the opposite side of the street, providing music and fresh seafood before or after a stroll. The vibe is relaxed and carefree.

This scene conflicts with news coverage of La Paz. It usually revolves around two topics: drugs and violence. The Mexican papers illuminate the cartel violence, with banners on the front page proclaiming the latest murder in exclamation points. As an ecologist studying climate, I generally ignored the story of crime and violence of Mexico. I didn’t think it had anything to do with my life or my research.

Yet paceños (residents of La Paz) told me that the most powerful hurricane since 1967 had caused an uptick in violence, so I was curious. This hurricane packed more punch because of the impacts of global warming. I wanted to know if this created a perfect storm for violence: was there really an increase in cartel fighting after the storm?

How a Hurricane Stirred the Pot

On September 14th, 2014, Hurricane Odile veered suddenly from its projected course out to the Pacific and stomped ashore in Baja California. That night, 125-mile-per-hour winds slammed into the city. With a population weary from a season of false calls for hurricane preparation, Odile caught La Paz standing outside in its flip flops, unprepared (as my friend Jassiel literally was, standing bewildered and drenched at the onset of the storm outside an OXXO, the ubiquitous Mexican convenience store.) Stick-built structures and homes were destroyed, many gas station canopies collapsed, and roads were flooded and impassably torn apart. The entire city lost power for over 10 days. This included all the city and personal home pumps for water, so people used buckets to pull water out of their cisterns — if they were fortunate enough to have one. All but five of the 50 sailboats anchored in the harbor were washed into the mangroves on the short spit of land across the bay, and three people aboard their boats that night were killed.

According to residents of La Paz, Odile’s deadliest impact came in the two months after the physical damage. Teachers, business owners, and taxi drivers all told me, ‘of course’ the hurricane increased the violence. To those who lived through it, it seemed obvious. Battered infrastructure included destroyed cell phone, radio, and electrical transmission towers, as well as flooded roadways and hospitals full of citizens with immediate needs. Already weak emergency infrastructure and crime enforcement was hobbled by lack of supplies and the sheer number of people taxing the system. With all hands directed toward helping, rebuilding, and repairing, this left an opportunity for nefarious activity with impunity.

Organized crime means the death of young men and women swept into the narco violence, but it also means terror for local citizens, so they pay attention when the violence increases. People in La Paz started to change their habits to avoid potentially dangerous areas. One innocent man was killed in his living room by a stray bullet, and a 2-year-old was very recently caught in crossfire and killed. Residents of the city center now listen to gunfire every night, a new phenomenon since the hurricane. In the beginning of March, a car careened along the malecón at 2:30 a.m. and tossed a grenade onto the street in front of the most popular seaside nightclub. The pin wasn’t pulled, but the people of La Paz were shaken by that one: even their peaceful shore was unpredictably vulnerable.

Finding Proof

To quantify cartel violence and determine if there was an increase after the hurricane, one statistic that reflects this change is homicides. I knew the newspapers wrote about it, but unlike the United States, much of the local reporting is still only in print, not online, and what is online is challenging to search. When I started looking for information about local organized crime, I dove into the websites that describe the sad and gory details of the fighting. I found no statistics, but I read story after story of young men and women killed before the age of thirty because of their involvement in this mafia. The dark eyes of a slain 20-year-old stared back silently from a La Paz story: he looked young and vulnerable, not like a manipulative drug runner. This research was disheartening and getting me nowhere. I reached out to Daniel Peña, a writer from my Fulbright cohort in Mexico, and he suggested that I find a trustworthy journalist. Days later, I met with a cheerful and outgoing young reporter in a café on the malecón.

This journalist was one of the first on the scene at the burned car last July, and he described his fear as he realized that this was the work of a cartel. But he learned quickly that he could keep himself safer by keeping track of statistics instead of names.

He knew the monthly numbers off the top of his head. There were 35 murders in the two months after the hurricane, in comparison with fifteen in the two preceding months. There may have been others that went unreported in the electrical blackout that followed the hurricane.

A doubled murder rate is a significant change.

“After the hurricane, other cartels saw it. They saw the weakness. And they came in,” he told me. Allegedly, in July the local crime ring in La Paz experienced an internal fracture that caused infighting. But after Hurricane Odile, an outside group from Sinaloa exploited this division and the taxed infrastructure, escalating the violence and doubling the murder rate.

So can we say that the hurricane caused the murders? Not really. A scientific study to determine causation between hurricanes and increased cartel violence would require more examples over time. And gathering data in Mexico is notoriously challenging: it was a large task to find the right person who could share numbers with me for one instance in La Paz. More statistics very likely exist, but tracking down data in Mexico requires persistence, patience, and luck. So it would be possible to gather the evidence and create this study, given years of research, but I didn’t have the time.

Yet everyone from taxi drivers to emergency room doctors in La Paz state with confidence that the hurricane provided the disruption, and the storm enabled the ensuing carnage. This is the power of local knowledge and observation. They don’t need a scientific paper to know what happened in their home.

But have scientists been able to pin down this link?

The Science of Climate and Conflict

It turns out they have. In the past 10 years, researchers have sought — and found — evidence that climate change causes conflict. In 2013, Solomon Hsiang at UC Berkeley looked at 54 previous studies on the topic and found that “Climatic anomalies of all temporal durations, from the anomalous hour to the anomalous millennium, have been implicated in some form of conflict.” In other words, climate change can be scientifically shown to have a hand in conflicts ranging from five minutes of personal violence to five years of civil war.

But no one has looked at these kinds of climate impacts relative to drug trafficking — most likely because of the difficulty of collecting data. Once again, indications of the connection of climate and crime can only be found in the newspaper, not in the scientific literature. Stories precede the science.

Frustrated by the apparent lack of research, I tracked down Duncan Wood, director of the Mexico Institute at the Wilson Center in Washington, D.C., to find out if this scholar on Mexican conflict had heard anything about climate change and violence in Mexico.

“The problem is, organized crime is a complex phenomenon as is,” he told me, “without the addition of climate change. It has deep historical roots, as well as more proximate causes. It is interlinked with weak local and state level institutions in Mexico. It’s very difficult to say that climate and organized crime are linked when it’s such an embedded issue.”

He did note the case of climate-induced drought and organized crime in Sonora and Sinaloa. “The drought experienced in the last 10 years in the northern states of Mexico has exacerbated the [organized crime] problem. When there is no longer enough water to farm, you end up with a breakdown of family structure, migration to urban areas, and migration to the U.S. Young men who used to have a place in farming no longer have that opportunity and are moving into organized crime.”

I asked a Mexican friend, colleague, and scholar, Diego Ponce de Leon Barido, about Wood’s reply. Barido studies climate change and renewable energy development in Latin America. I was suspicious that his knowledge of historical climate phenomena and Latin American history made him uniquely positioned to understand the dynamic of the two in Mexico.

Barido replied that, contrary to Wood’s reply, it’s impossible to separate climate from the development of organized crime. “Mexico’s independence, revolution, and the current drug violence are each about one hundred years apart — and each tied to a severe, once-a-century drought that plagued the countryside and the farmers, pushing people past their tipping points. There are obviously other forces, but climate has always played a central role in Mexico’s historical progression.”

He continued, “Mexico has always been an arid agricultural economy – there’s no way for the country to escape its ‘dry years’ fate.”

The standard, textbook definition of the emergence of cartels, as repeated to me by Wood, is weak institutions and governance. However, examining only the failure of institutions ignores how humans, especially those directly dependent on the land and sea for income, are deeply shaped by the natural world. And we all depend on the land and sea for the most basic human need: food. When this is first compromised, it is then that weak institutions are exposed and taxed as humans are forced to survive in new ways.

So how can La Paz, and the rest of Mexico, cope? As Hsiang stated in the climate and conflict study, the findings “suggest that coping or adaptation mechanisms are limited.” Mexico appears vulnerable to the interwoven fate of climate and crime.

Solutions in Surprising Places

Instead of looking at the outcome — cartel violence — I dug deeper into the non-climatic roots of the violence. One of the most powerful global solutions to poverty and conflict is education. Yet Mexico ranks 124th (out of 144 countries) in the world in primary school education.

It’s the poor students who suffer disproportionally in Mexico’s system. For example, there was a three month teacher strike this winter in La Paz because teachers weren’t paid for those 90 days by their employer: the government. Without wages, they were forced to strike. Middle-class parents put their kids in private school, but those who couldn’t afford it were left with kids receiving no formal education for three unexpected months. In a country with an average wage of five dollars per day, where 53 million people — half of the country’s population — live in poverty, I can understand why only 37 percent of adults have completed high school. It’s easy to imagine that these kids, left to the streets for months at a time without money or guidance, find both within organized crime.

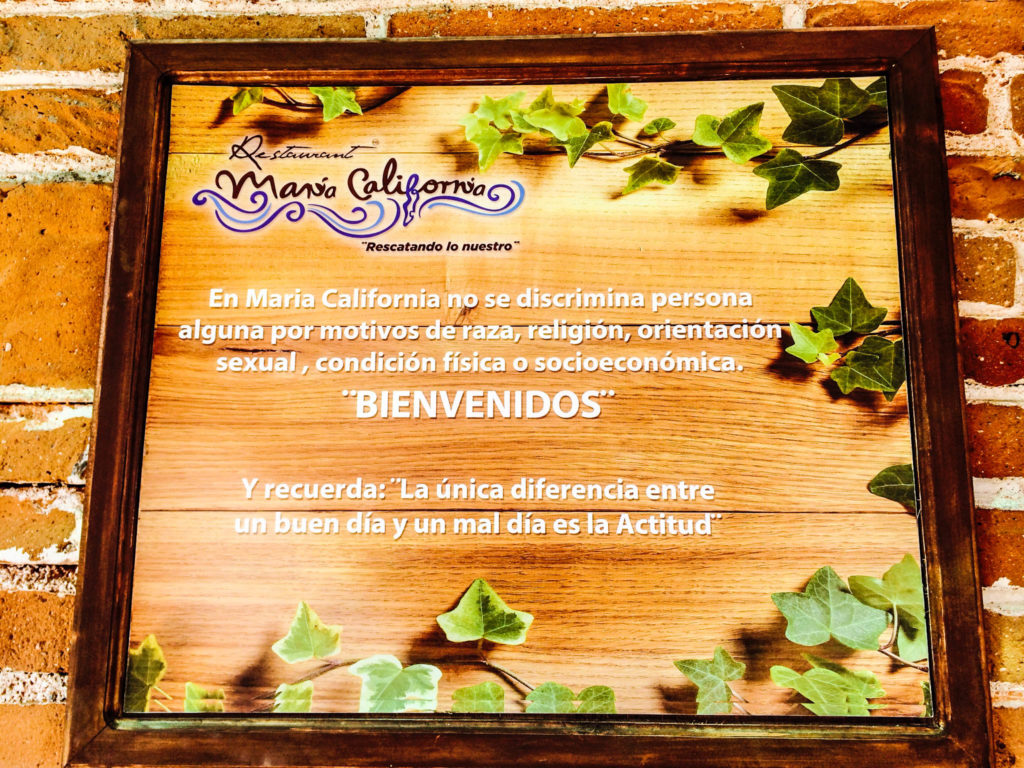

Addressing crime and climate change in one breath can feel like a quagmire of hopelessness. But there are individuals, organizations, and businesses who support the youth of Mexico even as institutions fail. One of these businesses is Restaurante Maria California. This is one of my favorite restaurants in La Paz. There are only young people working here, college-age kids, and their expedience and politeness matches their smiles and industrious hustle as they bring liters of fresh juice and traditional Mexican dishes to every table. Turns out the owner of this restaurant employs college students, from all economic backgrounds, so they can pursue and finish their academic studies.

“Origen no es destino,” Brenda says firmly with a smile. Where you come from is not your destiny. Brenda is the owner of this rustic restaurant wrapped in bougainvillea. Her lips match the magenta flowers, and her positive energy hugs the restaurant in the same way.

Brenda grew up poor in Mexico City. “I was always asking ‘Why?'” she leans forward and laughs. “‘Why are they rich and we’re poor? Why do they have money and we don’t?'” After becoming inspired by a Deepak Chopra self-improvement book, Brenda moved to the U.S. and owned a successful sandwich shop in San Diego until the 2008 economic downturn closed her business. She ended up in La Paz and saw an opportunity to build a new restaurant here based on the values of excellent service for customers, the community, and for Mexico’s heritage.

But she didn’t forget her roots. Most of her young employees come from poor communities. She calls two servers, Jesus and Daniel, over to the table. Jesus smiles shyly and tells me that he studies, works, and has two kids. Daniel grins and chatters so quickly I have to ask him to slow down. He wants to study in Cuba to become a physician. I ask him how Maria California helps him.

He pauses for a moment, then beams. “They’re like my second family, I don’t know where I would be without them,” he says, glowing.

“We are more when we’re together,” Brenda says after they both politely excuse themselves and walk away. She sees herself as a “force of improvement” for Mexico, and she uses this phrase with convincing emphasis.

Brenda and her restaurant, a private business with a social mission, is unusual in La Paz. But where there is one, there is room for others. This woman with roots in poverty has brought success to her restaurant by bringing success to her young employees. If the government can’t help Mexico’s youth, Brenda provides a glimmer of support, both social and financial, for educating the young people who might otherwise not know where to turn.

There are other ways to support Mexico’s youth in La Paz, such as nongovernmental programs that also connect kids with their natural world. Non-profit organizations such as Niparajá, Ecology Project International, and Como Vamos La Paz all have community outreach in La Paz grounded in years of experience in the region. In this way, they fight crime at the source — they give kids and parents knowledge and a voice.

****

The damages from Hurricane Odile continue their indirect impact on La Paz. This winter, La Paz faced an 80 percent decrease in tourism, according to one local newspaper. Many local businesses suspected that tourists stayed away because of the increased violence; others suspected that the hurricane and the following cool weather in the winter — both a result of a powerful El Niño — kept them away. Both of these reasons are tied to our warming climate and its more powerful, disruptive storms such as Odile. This is the insidious impact of climate change — it works in concert with weakened systems.

It’s easy to wallow in this sad tale, or rather this tale of two woes intersecting. But in La Paz, I find myself inspired by the ways in which people help each other amid these changes. It can be easy to forget that it is individuals that make up drug cartels and greenhouse gas emitters — and individuals as well who start and lead research, businesses, and revolutions. Support and education can come in less traditional forms than a classroom. It reminds me of a cartoon of a politician standing on a plank overhanging the edge of cliff. A small group of people stand on the other side of the plank, and one is turning to step off the plank. If the people move, the politician falls. The caption reads “The people don’t know their true power.” Power simmers in the hearts of Brendas in Mexico, and their voices and solutions could illuminate a better path in an irrevocably changing world.

Humidity and summer heat hang heavy over La Paz as the hurricane season looms, and the cartel violence continues. But the tipping point will come. ‘Origen no es destino’ can play out in many different forms, and Mexico has yet to decide which path it will choose.