CHANIA, Greece — Stepping off a plane at the airport here, the capital of western Crete, the first thing I noticed were the snow-capped peaks of Lefka Ori, the White Mountains, towering to the south. At 2,453 meters tall, the limestone range is covered in snow most of the year. From my apartment in the city, I could see the range from one direction and brilliant blue Aegean Sea from the other. Over millennia, snowmelt from the mountains carved caves and gorges into Crete’s rugged terrain, seeking outlets in the Cretan and Libyan seas. The 16-kilometer Samaria gorge south of Chania attracts thousands of visitors a year.

During my first weeks on Crete, I hiked lesser-known gorges like the Sarakina between the villages of Meskla and Zourva, whose smooth gray walls curved around me like two cupped palms parting to let water drain. North of the airport, I explored the Gouverneto gorge, a two-hour hike from the beach of Stavros, where the famous final scene of the 1964 movie “Zorba the Greek” was filmed, to a complex of monasteries by the sea. After meeting only shaggy, grazing goats, I turned a corner to find the 11th-century Katholiko monastery rising out of gray-orange rock, its shrub-laced stone bridge arching across the gorge.

Stumbling across one of the island’s oldest monasteries at the bottom of the gorge seemed to emphasize how well Cretans have adapted to their craggy homeland. Vice Governor for Tourism and e-Governance Kyriakos Kotsoglou, a Chania native, affirmed the mountains’ unique role in shaping Cretan character. “Crete draws its history from the mountains,” he told me when we met in Heraklion, the island’s capital and largest city. “It’s where its songs were written, where its battles started. We may be an island with 1,100 kilometers of coastline, but we’re actually mountain people surrounded by sea.”

Crete’s mountains have an honored role even in Greek mythology as the birthplace of the thunder god Zeus. While visiting Crete during my Fulbright fellowship in 2017, I descended into the stalagmite-filled cave of Dikteon Andron and peeked into the black mouth of Ideon Andron, two caves claimed to be the cradle where Zeus was raised in secret until he was old enough to overthrow his father Kronos. The mountains were also home to peak sanctuaries of the Bronze Age Minoan civilization where ancient religious rites were performed.

Influenced by daily contact with the harsh mountains, Cretans are a hardy, self-sufficient people. According to Kotsoglou, Crete is considered one of the few “autonomous” regions of the world, meaning it can survive on what it produces and is one of a handful of Greek islands, like Chios, whose economy doesn’t depend solely on tourism.

It is home to over 600,000 people who have a reputation for extremes. “They are either the best, kindest people or the worst,” says my friend Stefanos, whose partner is from Chania. Indeed, the recent Greek television series Sasmós (“reconciliation” in the Cretan dialect) dramatizes the bloody vendettas and penchant for firearms that have made the island infamous.

Anna Markoulidaki, one of my Greek language instructors, an artistic, well-read woman with a severe black bob, expanded on that paradox. “In general, Cretans are warm, lively, dynamic, full of humor and wit, inventive, honest, generous and uniquely hospitable,” she wrote me in a pages-long email when I told her I was headed to her home island. “On the other hand, they are proud and sensitive in matters of honor, so they are very fierce, friends of fighting, fearless, daring and reckless. They love their friends to the point of self-sacrifice and hate their enemies without mercy.”

With a surface area of nearly 8,500 square kilometers, Crete is Greece’s largest island, the fifth largest in the Mediterranean. It is double the size of the northeastern Evros region and ten times the size of Chios, my other two bases. Crete is also the southernmost point in Europe, and while Greeks don’t often consider it a border region, its strategic position between Europe and Africa has made it a prized possession and cultural crossroads since the Minoan civilization flourished there around 1900 BCE.

I plan to stay on Crete until early September, slowly working my way east and writing about how the island’s strategic geographic position has influenced its history, the makeup of its population and its attractiveness to tourism, while creating opportunities for new energy projects linking Europe and Africa and aiding in the projection of NATO military power in the region.

Nikos Kazantzakis, author of Zorba the Greek and arguably the greatest Greek novelist of the 20th century, wrote, “Crete doesn’t want homemakers, she wants madmen. These madmen make her immortal.” I’m eager to spend time with the island’s madmen, absorbing Crete’s wild spirit.

From Minoans to Mitsotakis

Crete has been inhabited since at least the Neolithic Period (6500 to 3000 BCE) and is best known as home to the Minoans, an advanced civilization that flourished from approximately 3000 to 1100 BCE, trading from Egypt to Asia Minor and building the palaces of Knossos, Phaistos and Malia. In Greek mythology, the hero Theseus sails to the island to slay the minotaur, a man-bull hybrid who devours human sacrifices in its labyrinth beneath Knossos. Archaeologists have also discovered a Minoan settlement beneath the town of Chania, and there is evidence to suggest it, too, was a palatial center. It is believed that the Minoan civilization declined due to an explosive volcanic eruption on Santorini around 1500 BCE, internal strife or violent invasion from the mainland.

Since then, Crete has been occupied by Myceneans, Dorians, Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, Venetians, Ottoman Turks and Germans, all of whom sought control over the island’s valuable sea routes. In Chania’s old town, you can walk along the circular Byzantine fortification walls as well as the more extensive, roughly trapezoidal walls and bastions built by the Venetians in the 16th century in response to a growing threat from the Ottoman Empire.

As I learned at the Historical Museum of Crete, the Ottomans invaded in 1645 and finally gained control of the island in 1669 after a 20-year siege of Heraklion. The victory cut Crete off from the West and established a strong Muslim minority on the island. Like on Chios, several minarets, hammams and fountains remain in Chania, attesting to the Ottoman presence.

After Greece declared independence in 1821, the Orthodox Christian majority in Crete fought enthusiastically for union with Greece, trying seven times to throw off the Ottoman yoke, often to violent reprisals. Gikas Michailos, a young lawyer from Heraklion, told me that Cretans understood the meaning of patrída or “country, fatherland,” because they fought heroically for that idea, something bigger than themselves. The European great powers intervened after a final uprising in 1897, declaring Crete an autonomous state with Chania as its capital.

During this period, Eleftherios Venizelos, a lawyer from Chania, entered the political spotlight. He sought to hasten Crete’s union with Greece, breaking with Prince George, the island’s high commissioner. Venizelos led a 1905 revolt that resulted in the prince’s resignation. He went on to serve as Greece’s prime minister seven times from 1910 to 1933. A skilled statesman, he doubled Greece’s territory through his diplomacy, expanding the state to include lands Greeks had inhabited since antiquity.

He was also a divisive figure, a political outsider whose rivalry with King Constantine over whether the country should enter World War I polarized Greek politics for decades. As the historian Roderick Beaton wrote, the “National Schism” between the royalists and Venizelists was essentially one between “Old Greece,” the territory before 1912, and “New Greece,” the lands of Epirus, Macedonia, Thrace, Crete and the northeastern Aegean islands gained after the Balkan Wars.

Venizelos’s residence in the suburb of Chalepa, his birthplace in the village of Mournies and the headquarters from which he led the 1905 revolt now operate as museums. In Chalepa, you can walk through rooms where Venizelos lived with his second wife, Elena Schilizzi, whose family came from Chios. You can see the gold fountain pen he used to sign the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres, which granted Greece territory in Thrace and Anatolia as well as a mandate to occupy Smyrna.

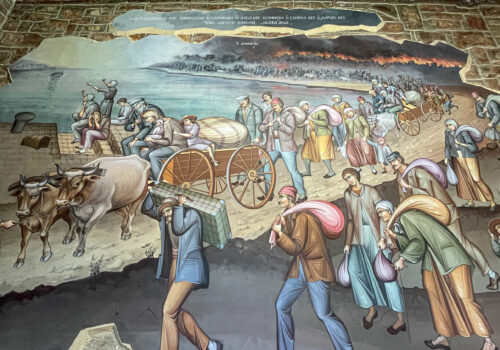

Following the 1922 Asia Minor Catastrophe, Venizelos also negotiated the Treaty of Lausanne, which set the current border between Greece and Turkey and stipulated a mandatory exchange of populations that displaced 1.3 million Orthodox Christians from Turkey and 400,000 Muslims from Greece. The population exchange links all three regions where I’ve been based.

Last November, I traveled across the strait from Chios to Izmir (formerly Smyrna) to research the history of Hellenism in Anatolia and meet Cretan Muslims who had resettled in the neighborhoods of Bornova and Eşrefpaşa. I’ve also run into Anatolian Greeks across Crete including Vice Governor Kotsoglou, whose father is from Smyrna and who retains a Smyrniot eloquence and disheveled charm. I will share their stories in my next dispatch.

The Germans occupied Crete during World War II and used Venizelos’s residence as a headquarters. For Crete, those were years of deprivation, curfews and forced labor. Civilians resisted from the first days, helping a British major named Patrick Leigh Fermor abduct a German general, for example, and sabotaging airfields and munitions depots. German reprisals were harsh: They burned entire villages to the ground and executed Cretan males en masse.

That’s one reason why, at the height of Greece’s recent debt crisis, an overwhelming majority of Cretans voted “No” in a June 2015 referendum asking whether Greece should accept the EU’s bailout conditions. Chania recorded 73.27 percent opposed—the highest in the country.

Although the incumbent Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis hails from Chania, part of a political dynasty descending from the Venizelos family, Crete has historically been a leftist bastion, and the island backed the left-wing Syriza Party in elections in 2019. The Mitsotakis family is not highly esteemed in Crete partly because Kyriakos’s father Konstantinos defected from the center-left government of Georgios Papandreou in 1965, heralding a period of political instability that paved the way for Greece’s military dictatorship two years later. However, Mitsotakis’s conservative New Democracy party took Crete for the first time in decades in the first round of parliamentary elections this May. With a landslide victory in round two, he won a second four-year term.

First impressions of Chania

Crete is by far the most touristic of the three regions in which I’ve lived. When I arrived in Chania in January, the city was in hibernation mode: most shops and restaurants in the old town were closed as locals traveled, renovated and recuperated from a frenetic summer season. Storms rolled over the island. Once, during a nine-hour hike from the village of Theriso to the monastery of Agia Kyriaki, I was caught in a two-hour downpour that soaked me to the bone. The sun came out and dried me off, and luckily I made it to my bus before a second storm hit just after sunset.

The quiet period gave me a chance to connect with a vibrant and diverse community catching its breath. I met local architects and archaeologists, Greek-American artists and restaurateurs, a Dutch walking guide who lived on the island year-round and wrote the guidebook series Discover… on Foot and a Fulbright fellow collaborating with the Etz Hayyim synagogue.

A number of Greeks who had moved to Crete shared the opinion that while people in Chania were warm and friendly to tourists, the society itself could be insular and conservative. One told me that locals called foreigners living on Crete xenobátes, a word that implies “intruder,” and kaltsounádes, meaning “Athenians who come to eat and take home Crete’s iconic hand pies.” She believed this snobbish attitude grew out of a mix of pride and insecurity, especially for those who had never left the island. Several locals also bemoaned that wealth from tourism and the desire to profit from visitors had changed their compatriots for the worse.

As summer approached, Chania became a flurry of activity. One morning in March, I went for a walk in the old town, and at every restaurant and cafe, the staff was out repainting tables. The bountiful island is one of Greece’s most popular tourist destinations. Last year, it hosted some 6 million visitors. But with popularity have come rent hikes and overcrowding, which threatens the island’s sensitive ecosystems. I will write about tourism on Crete and efforts to create a more sustainable, environmentally friendly product. I also plan to report on the LGBTQI+ community in Heraklion as it prepares a self-organized Pride festival in July.

Finally, I will investigate how Crete has retained its geopolitical significance to this day. The island is home to US Naval Support Activity Souda Bay, a unique military installation used by European, Central and Africa Command to project power in the eastern Mediterranean. I visited Souda Bay in 2020 with then-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, and I want to see how it has changed with the 2021 update to the bilateral Mutual Defense Cooperation Agreement.

Like Thrace, Crete is also emerging as a hub for projects meant to enhance European energy security. I look forward to reporting on new electricity interconnectors between Greece and Egypt that will link the grids of Europe and Africa, carrying renewable energy from north Africa’s wind and solar farms to Greece and its neighbors. Greece’s hydrocarbon exploration off the coast of Crete has also elicited strong reactions from Ankara.

The mask makers of Sivas

For me, the greatest joys on Crete so far have come from leaving the city and exploring the hinterland or endochóra, where you can hike through awe-inspiring landscapes without seeing a soul, and where Cretans devote themselves to preserving traditional handicrafts and customs.

In February, I drove to the village of Sivas near Phaistos, where Odysseus Messaritakis and Titos Tagarakis, two white-haired men from the Cultural Association of Sivas “Themos Kornaros,” took me to see the carnival masks that Messaritakis has been carving from the roots of agave plants since he was 13 years old. Painted black and white with ghoulish red tongues and red-rimmed eyeholes, eight horned and mustachioed masks sat on shelves in the association warehouse, grinning at me in the dark. They were enormous, each about 70 centimeters tall, and heavy, too. To wear them, you have to hold the bottom of the mask and stick your face through a hole cut in the back.

Unfortunately, there weren’t enough young people in the village this year to participate in the carnival custom. Tagarakis, the president of the association, told me they wanted to make a mask museum and host workshops. The men treated me to coffee, and then Messaritakis gave me a tour of the village. He had lived in Germany for many years and often switched from Greek to German in mid-sentence. “You’re staying for lunch, right?” he asked me. We enjoyed a traditional bean soup in the square to celebrate the start of Lent, and he and his wife made sure my plate was full and I wanted for nothing.

When I think about all the contradictions Crete embodies, I remember my eager hosts in Sivas and the demonic masks they made. Kotsoglou emphasized that “hospitality from the heart” is a defining feature of Cretan culture, linked to Zeus and the altar where Minoans placed their offerings. It’s rooted in Cretans’ deep pride in their homeland and their desire for strangers to share that pride. The love of strangers, even at one’s own expense, Kotsoglou said, operates with a “completely different logic compared to Western standards.” It creates a powerful bond of friendship between guest and host, just as whenever I think of Sivas, a smile crosses my face and I look forward to return.

Top photo: Chania’s Venetian harbor in January 2023