HERAKLION, Greece — On July 10, four days before this city’s self-organized Pride festival, Anna Ivankova, a Black transgender woman who had immigrated to Greece from Cuba, was murdered in her Athens apartment. She died of hemorrhagic shock after being repeatedly stabbed; the police arrested a Bangladeshi man in connection with the murder.

I was pained and enraged by news of yet another queer person brutally murdered in Greece. In the seven years I’ve lived here, there have been at least two others. Zak Kostopoulos, a Greek-American LGBTQIA+ activist, was killed in broad daylight, beaten by civilians and police on a busy street in central Athens in 2018. Another transgender woman, Dimitris or Dimitra Kalogiannis of Lesvos, was struck by a hit-and-run driver in 2021.

News of Anna’s death spread quickly over social media, shared and reposted by gay friends in Athens, queer-friendly Greek organizations like the Onassis Stegi and then by the Heraklion Initiative for a Self-Organized Pride, the assembly responsible for planning the Cretan capital’s three-day festival of gender, body and sexuality. The organizers, mostly leftist and anarchist LGBTQIA+ university students and young people, called for a rally in Heraklion’s central Lion Square the next day. “We were all shocked at the news of her murder,” the group wrote in a Facebook post, “not because we believe that femicide, homotransphobia and racism are not everyday life in Greece, but because we categorically refuse to get used to it.”

Anna performed regularly at Koukles, a popular drag venue in Athens. The 46-year-old dancer came to Heraklion Pride in 2018 to represent her group “LGBTQIA+ Refugees Welcome.” She was a “pleasant person, always smiling and quite helpful,” one of the organizers told me. “During a show with local drag queens, Anna got on stage and started dancing completely spontaneously.”

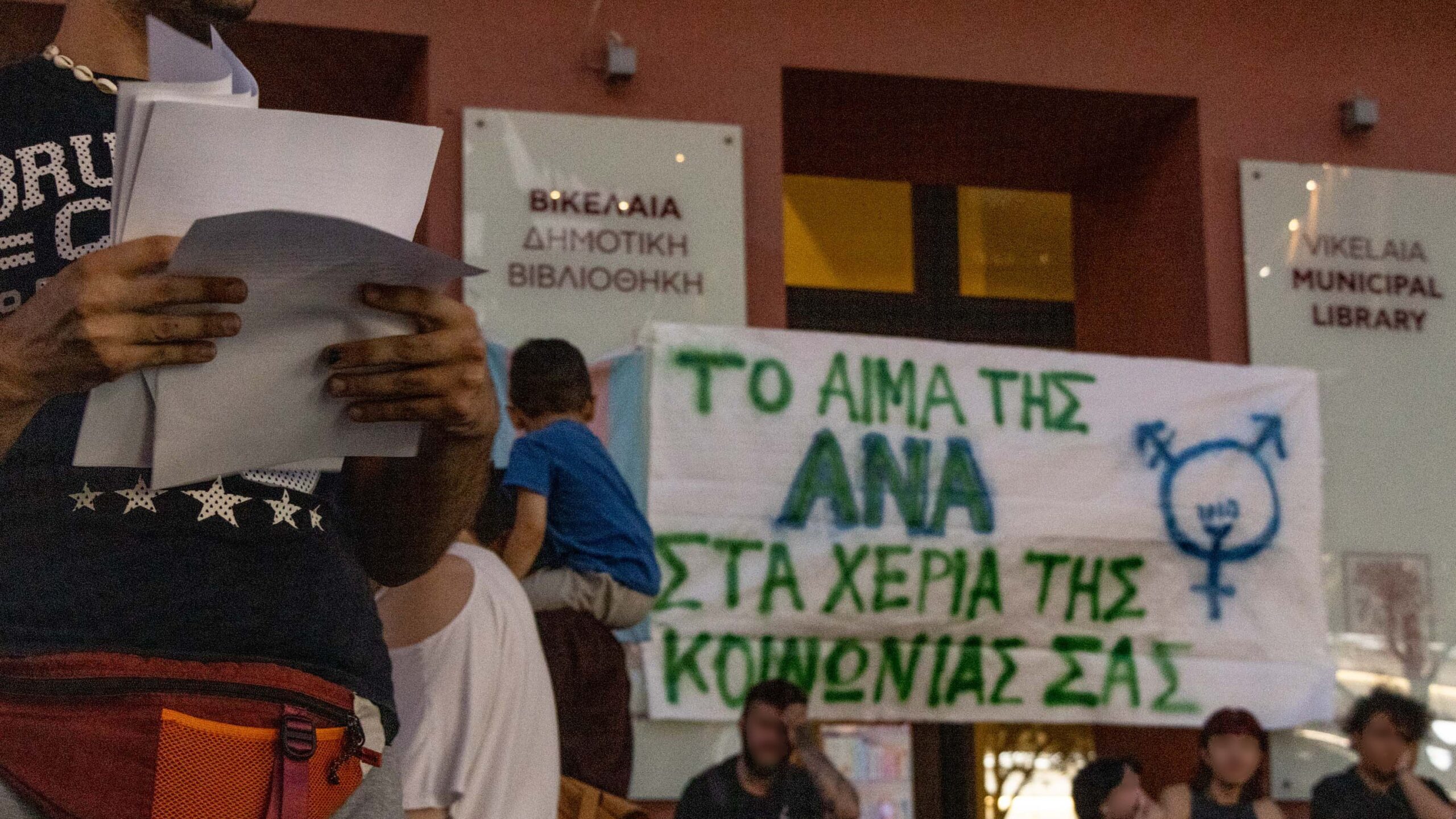

When I arrived at Lion Square the following evening, the Pride assembly and its supporters were sitting on the steps of the municipal library, handing out fliers to passersby. Many of them were dressed in black with tattoos or piercings, their hair partly shaved or bleached. Across the library entrance, they had taped a baby-blue, pink and white trans flag and a poster that read, “Anna’s blood is on our society’s hands.”

Members read a statement over a portable PA system that charged Greek news outlets of misgendering Anna as a man in their initial reports, “not respecting her gender even in death.” When the speaker’s battery died after the first reading, the group chanted slogans like “Orgí kai thlípsi, i Anna tha mas leípsei,” which translates to “Anger and grief, we will miss Anna.” The demonstration seemed to be working: Out in the crowded square, I heard tourists ask, “Who’s Anna?” Men sitting at nearby cafes waved for copies of the flier.

Although the situation in Heraklion has improved in recent years and there are spaces where queer people feel they can be themselves, harassment is not uncommon. Later that evening, at the end of an impromptu march through the city center, the organizers reported that they were verbally and then physically attacked by six young men on a pedestrian street.

“When we talk about homophobia and toxic masculinity, I feel greater danger in Crete,” said Nefeli, who asked me not to use her last name. She and her partner Danai Gouniaroudi came to Heraklion for their studies and met during a pre-Pride event this year. Τhey both helped coordinate the festival, and Nefeli was responsible for the live shows. Walking home late at night holding hands, she said they’re often yelled at by “wankers.” Danai agreed. “When I arrived in Crete, I didn’t have this fear, this unease,” she said. “It was created completely from experience.”

Vasilia, a local who joined the organizers’ assembly this year, told me that in smaller cities like Heraklion, participating in Pride entails a greater personal risk. “The people who march and wear the Pride flag risk a bit,” she said, and for that reason, she considers the annual festival all the more necessary. “Despite our assembly’s flaws and difficulties, in the end, we’re some 10 people and we created space for people who have a need. We created conditions for discussions, exchange of experiences. It’s very important.”

In the weeks leading up to Heraklion Pride, I embedded myself within the organizing assembly, following its debates, dramas and discussions as it planned and executed the three-day festival. The experience offered me a unique glimpse of queer life in the Greek province, and the young planners’ commitment to organizing a diverse, inclusive festival on their own terms left me feeling optimistic about the future of Greece’s LGBTQIA+ movement. Their efforts are a lifeline for queer people in Crete, part of a larger movement that is slowly shifting Greek society and creating political consensus about the need for equal rights.

‘We have a long road ahead of us’

Greece is a largely conservative country where roughly 90 percent of the population identifies as Orthodox Christian and priests regularly inveigh against the queer community. In March 2021, Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis, the leader of Greece’s center-right New Democracy Party, formed a committee to prepare the country’s first national strategy for LGBTQIA+ equality.

The government has since banned conversion therapy for minors and abolished a prohibition on blood donations by gay men. Perhaps even more important, the Hellenic Police has undergone training programs to raise awareness about issues relating to sexual identity and gender expression. The Education Ministry will also train teachers to address homophobia and transphobia in schools, according to a government source.

As a result of those reforms, ILGA-Europe, an independent, non-governmental umbrella organization that tracks LGBTQIA+ rights and equality, raised Greece’s score on its Rainbow Map from 47 percent in 2021 to 57 percent in 2023. Greece now ranks 13th among 49 European countries, above Germany and the United Kingdom. After winning reelection in June, Mitsotakis announced plans to legalize same-sex marriage during his second term. “Now the LGBTQIA+ agenda is no longer exclusively a leftist agenda,” my source told me. “Accepting equal rights for queer people is slowly but steadily becoming a part of New Democracy’s political ideology.”

When I asked members of the assembly how they felt about Mitsotakis’ announcement, they responded skeptically. “I think it’s simply something they say they’ll do to keep people close to them,” said Nefeli, who describes herself as an anarcho-feminist. “And even if they do legalize same-sex marriage, it would be to obtain economic profit from the European Union.”

There was a consensus among those I spoke with that much work remained in the struggle for even basic rights, especially health benefits for trans and nonbinary people, combating discrimination in the workplace and bullying in schools, and raising public awareness so queer people can express themselves freely. Vasilia, Nefeli and Danai felt that issues related to health and survival deserve more immediate attention from the government than marriage equality. “When you don’t know day by day whether you’ll live or not,” Nefeli said, “you don’t give a shit whether or not you can get married.”

While I’ve seen the country make progress in LGBTQIA+ laws and representation over the past seven years, I’ve also observed a wide discrepancy between queer life in Greece’s biggest cities and its provinces.

The few queer people I got to know in the northeastern prefecture of Evros were not out to their families or workplaces, for example. One gay man told me that the guys he spoke with on dating and hook-up apps like Grindr often asked to meet by the river instead of going out for coffee so they wouldn’t be seen together. Or, if he told them he was a local, they would stop chatting with him all together in case their social circles overlapped.

He also told me that while it was much easier to meet guys in Athens, he felt many there, too, were still partly in the closet or had internalized homophobia. While working the summer on Mykonos, he said he met gay couples from abroad who were at a totally different level, out and proud.

Joining the Heraklion Pride assembly

A month before Anna’s murder, I showed up at the queer hang-out Queen of Hearts to introduce myself to members of the Heraklion Pride initiative and ask to participate in their weekly meetings. I’d met few LGBTQIA+ people since I left Athens to begin my fellowship almost two years ago, and I felt an immediate sense of ease within the group that I didn’t realize I’d been missing.

Its members were committed to “horizontal and anti-hierarchical” decision-making, and this was clear in the way they communicated, raising their hands to speak and taking care not to talk over each other—practices that seemed decidedly un-Greek to me. They also used a vocabulary I was familiar with from the United States, referencing the influential gender theorist Judith Butler and terms like safe space, victim blaming, pinkwashing and microaggression, some so freshly imported they don’t yet have Greek equivalents.

The assembly’s processes, while creating a supportive, inclusive environment and enabling members to share opposing opinions freely, also resulted in meetings that dragged on late into the night and discussions that veered from the practical to the theoretical, making it difficult to reach decisions, especially when unexpected issues arοse. Evanthia Xanthaki Chauliac, a local who has helped organize the festival on and off since the city’s first Pride in 2015, told me the meetings could be quite tiring, and groups from previous years had disbanded after the festival due to infighting, explaining the redundant social media accounts.

When I asked why she continued to participate, she said, “In the past, I would have answered, ‘Because I have to! Because of our rights!’ But it’s become a way to socialize, to meet people. It creates a bubble, a safety that’s incredibly strong, where you can discuss gender, neurodivergency, fatphobia. And when you grow up, live and work with exactly the opposite, that in itself is a huge draw.”

Another element to which I had to adjust was the self-organized nature of Heraklion Pride. The coordinators were determined to mount the festival without help from local institutions, political parties or businesses that, according to their statement, “use our struggles as a washing machine for the oppression they themselves (re)produce.”

In this way, the festival distinguishes itself from more institutionalized celebrations in Athens and Thessaloniki. Nefeli described Athens Pride as “glitter and froufrou and aromas and cops everywhere, which surely doesn’t express the origin of Pride, starting from Stonewall.” There have been disagreements in the assembly about how political Pride should be. Some believe the political element should be emphasized more while others don’t feel such a need.

Although the assembly isn’t tied to a political party, it is linked to the city’s Evagelismos anarchist and antiauthoritarian squat, mainly through the squat’s feminist group. Participating in the weekly meetings introduced me to another side of Heraklion, a passionate and outspoken youth culture with a vibrant network of like-minded groups that railed against fascism, sexism, racism and patriarchy while supporting workers, migrants and refugees and other oppressed groups. Its members all know the same slogans and pass around motorcycle helmets to collect funds to support comrades in other parts of the country. However, their anti-institutional mindset sometimes conflicts with organizers’ efforts to promote and fundraise for Pride.

In order to maintain financial independence and creative control, the assembly runs various pre-Pride events to raise money for the three-day festival, which by conservative estimates costs some 2,500 euros. The organizers hosted an outdoor fundraising party in May, but due to the increased cost of alcohol and inclement weather, the party didn’t bring in as much income as they’d hoped. The group’s decision to do live rap and punk shows on the second night instead of the usual DJ set resulted in additional expenses they had not anticipated.

Vasilia, who works in a ceramics shop, proposed selling multi-colored mugs with rainbow paint splatters and phrases like proud, queer, born this way and ask my pronouns emblazoned on them. “For such an assembly, to say the words shop, store or business is a red alert,” she told me. Though it was easier to proceed with the mugs since Vasilia worked for the store in question, there was greater disagreement when two other local shops offered to make products to support Pride. Some worried the group’s reputation would be jeopardized if people thought they were accepting sponsors. Others wondered if the businesses were participating to promote themselves.

“I think there should be a place for people who want to support us, who have built their businesses with their own labor and sweat,” Vasilia said. “It’s different from approaching Zara or McDonald’s.” The first run of 31 mugs sold out in two days, and a second run of 20 mugs sold out as well. The assembly asked for voluntary contributions, suggesting 10 euros each, though people could give as much as they wished. “Knowing the funds we had, the mugs and the prints, shirts and bags we sold at Pride were a salvation,” she said.

Safety during Pride was a foremost concern for the organizers, many of whom felt an obligation to protect those they had invited, especially vulnerable groups like kids attending for the first time or mothers trying to understand what their queer children were going through. That is one reason the group worked with the municipality to obtain permits to use Georgiadis Park for the festival rather than simply squatting.

On June 29, Vuziballs, a group in western Crete’s capital of Chania, planned the city’s first LGBTQIA+ visibility march. That week, three far-right parties entered the Greek parliament during a second round of elections, accounting for 34 of the 300 seats. Fresh off their victory, local candidates from the Spartans Party, which is backed by the jailed leader of the neo-Nazi group Golden Dawn, called for a counter-protest on the day of the march to “defend values and the innocent souls of our children from the perverted filth of the LGBTQIA+ community!”

The Spartans’ call drew such a massive anti-fascist response that the organizers canceled the counter-protest and deleted their social media posts. Members from the Heraklion assembly traveled two hours to Chania to support the march even though it was held during the workweek. “The fascists never appeared,” Evanthia reported when I messaged her to ask how it was going. “Because of them, quite a lot of people came to support the march. Lots of straight people, children, families. And tourists passing by greeted us and raised their fists.” Chania Mayor Panagiotis Simandirakis also attended the march and posted videos on his Instagram account.

The evening of Anna’s murder, I took part in a large meeting at the Evagelismos squat to discuss safety measures for the upcoming Pride. Although I felt a bit out of place among the pierced and tattooed comrades, I was also honored to be included in such sensitive discussions and impressed by how many had come out to ensure the safety of this year’s festival. I realized then how privileged I’d been to be able to take my own safety for granted. As Nefeli told me later, taking precautions to guarantee the events would be as safe as possible was the biggest challenge in her mind during this very frightening time.

Photographing Pride

On Friday July 14, the first afternoon of Pride, I arrived at Georgiadis Park with my camera and a chilled, two-liter water bottle, my shirt already sticking to my chest. The organizers and I greeted each other by complaining about the heat—it was all anyone could talk about. Greece was suffering through heatwave “Kleon,” with temperatures set to rise above 40 degrees Celsius on Friday and Saturday. I was thankful we’d chosen to hold the festival in the newly renovated park, one of the few shaded public spaces in the city.

I’d volunteered to photograph the festival, and in the days leading up to it, I had several conversations with the organizers about how I should take pictures in order to respect participants’ privacy. The assembly wanted to create a safe space where people could relax and be themselves even if they weren’t out to friends and family. Indeed, those on security duty were instructed to stop onlookers and media from taking photos or videos. We agreed that I would avoid photographing participants’ faces unless they gave me their explicit consent, and also that I would upload my photos for the assembly’s review and not post anything directly to social media. On the first day, they gave me a glittery pink badge to show I was with the assembly.

So I was a bit shy at first, unsure if anyone besides the organizers and performers would want me to take their picture. I started browsing the tables where queer artists, makers and designers were selling their work, and I was intrigued by the playful, irreverent and ecstatic nature of the zines, pins and clothing on display. I struck up conversations with the creators, and most let me take their photos. Photography became a way to introduce myself, a job that gave me exclusive access and a service I rendered. Many of the coordinators were happy I could document the festival since they rarely had time to take pictures, and several of the performers and participants asked if I could send them photos I’d taken.

At a neon-pink table, I met Stella and Than, a team from Athens that 3D-prints multi-colored self-defense toys in the shape of cute cat faces with pointed ears. Stella told me she’d wanted to experience Pride in the provinces, especially since a self-organized festival was closer to her political beliefs. “Athens Pride is drowning in corporations, and it doesn’t offer something to me personally,” she said. Here, on the other hand, she felt moved and strengthened by people who visited the booth who were not yet out or whose parents forbade them to attend.

As the park filled with people dressed in their Pride finest—hair dyed pink, bejeweled and painted faces, revealing outfits, bold colors—I felt the exhilaration of our for once being the majority. In Crete, so many LGBTQIA+ people felt like outsiders, constantly under threat. Seeing the park awash in exuberant, joyful colors, protected by patrols from the squat, it seemed they could finally breathe a sigh of relief and revel in their visibility.

My favorite moments of the weekend included reading a Richie Hofmann poem I had translated into Greek during the open mic on the first night; watching people with rainbow wings, umbrellas and flags flood the streets of Heraklion during the midday march; and the live shows on the second night, which featured queer rappers, lesbian punk bands and a raucous drag show.

I especially enjoyed the performer Chloe Media, whose rap lyrics were sharp, clever and often ribald, and whose drag act involved playing a drag robot to narrations recorded on an artificial intelligence text-to-voice website. Chloe later told me the coordinators seemed like a “family” because “they really had each other’s backs.” She added, “They were very conscious of the performers’ needs and safety as well, and they told us there would be people looking out for us.”

For Vasilia, the talk on queer safe sex and vaginal health with an inclusive gynecologist named Amalia Savvidi was a high-impact event that attracted a huge response. Following Amalia’s presentation, the audience asked questions for nearly two hours. “She created a safe environment for everyone, including people who don’t go to a gynecologist because they have dysphoria or are ashamed or have had bad experiences in the past,” Vasilia said.

Of course, there were a few uncomfortable moments. During the march, I heard an onlooker say, “Keep it in the bedroom.” Another commented that it was impossible to “walk through the park in peace.” And I felt a bit conflicted when the punk group Les Viaies sang, “Tourists go home! Tourists go home!” and when I saw people with bandanas over their faces spray-paint slogans onto public buildings during the march. While such actions may have been expected, I was also disappointed that no one from the municipality attended Pride nor mentioned Pride on the city’s social media.

Stella, who has a sun allergy, told me that the delayed start of the march, around 12:30 p.m. during the heatwave, was very difficult for her to manage physically and was “close to the boundary of being ableist,” discriminating in favor of able-bodied people.

But all considered, queer joy and power suffused the weekend program. From the political opener and the intersectional conversation about queer immigration to the craft workshops and inclusive soccer game, the events also captured the diversity of LGBTQIA+ experience and tried to offer something for everyone.

The success of Pride and the large turnout was ultimately a testament to months of careful planning and to the skills, dedication and ingenuity of each member of the assembly. “There were a few bumps, but the whole Pride was organized with such good intentions that you can’t fault them for anything,” Stella said. “Other than the heat, which was horrible, I had a very positive experience.”

For coordinators like Nefeli, planning Pride enlarges her community and gives her a rare feeling of belonging. “Every year, I’m shocked by the network this process creates,” she said. “Now I know that if I need anything as a queer person, I have a circle to turn to for solidarity.”

Returning to my car late at night after the drag show, still wearing the Pride t-shirt with the pink and purple seahorse I’d worn to the march, I held my breath, quickly passing packs of young men roaming dark stretches of Georgiadis Park. Had I internalized some of the organizers’ caution? I remembered a slogan we’d chanted during the march: “Gay, trans, lesbians, priestesses of shame, we are proudly the disgrace of the nation!” I hoped my new friends would continue fighting because Greece needed their passion, creativity, bravery and rage.

Top photo: The first LGBTQIA+ visibility march in Chania drew thousands who came to support the queer community after the far-right Spartans Party planned a counter-protest (Giannis Angelakis)