VIENNA — The Czech ambassador to the United Nations, Ivo Šrámek, finished his opening remarks at the opening plenary session of the 68th Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) in March 2025 to cordial applause. The cavernous wood paneled room in which he spoke boasted four screens hanging from the ceiling that showed the live proceedings for those in the back seats. The chair’s table stood on a podium at the front of the room. Above it were multiple floors of windows where a small army translated each speech into English, Arabic, Chinese, French, Spanish and Arabic in real time for the convened delegates of 53 countries.

The ambassador’s statement, reflecting his country’s desire to promote public health and legal regulatory approaches to drugs problems, differed in substance but not in tone to the Deputy Secretary General of China’s National Narcotics Control Commission Shan Yehua, who had spoken before him, promoting greater law enforcement cooperation and prevention efforts. Both were delivered in the kind of monotone expected at such multilateral functions.

Then the commission chair called the American delegate. Recently appointed Senior Bureau Official “Cart” Wealand of the Bureau of International and Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs at the US State Department came to the lectern. But something immediately seemed off.

“I wish I could say the United States is pleased to be here but the truth is less sanguine: This meeting means that, in certain respects, we’ve failed,” he began. It was as if the United States hadn’t been the leading architect of the world’s drug policy regime for the past seven decades.

As he proceeded, it wasn’t clear exactly what the assembled delegates found most offensive. Perhaps it was his display of a photo of a young African American male overdose victim to justify his indignation even as American delegates in negotiations taking place outside the plenary were actively at work objecting to all mention of diversity, equity and inclusion from previously agreed language. Even the term “biodiversity” was not given safe refuge.

Perhaps it was his condemnation of Canada, Mexico and China—breaking diplomatic convention— for America’s overdose deaths while the administration on whose behalf he spoke was busy slashing its participation in and funding of the multilateral bodies in which engagement for solving such problems take place.

Perhaps it was the fact that after walking off to scattered applause, he boarded a plane back to Washington that night, leaving a skeleton staff of career civil servants to manage the turmoil he’d left behind. Only to then tie their hands by micro-managing their negotiating positions from Washington.

I came to the CND to better understand the role the Vienna-based United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) plays in global and local drug policy. What I walked into was America’s unilateral retreat from multilateralism leaving in its wake a more chaotic—but potentially more democratic—global rulemaking body.

The UNODC is the administrative body that supports the legislative Commission on Narcotic Drugs representing 53 countries. The CND’s mandate is to analyze the global drug situation through consideration of supply and demand reduction efforts and take action accordingly. While its resolutions are not legally binding, they are meant to guide countries developing their own national laws and inform UNODC’s priorities.

Thanks to powers bestowed on the commission by the 1961, 1971 and 1988 drug control conventions of the United Nations, the CND can also decide to schedule certain substances based on their risk level. Such decisions are legally binding for all UN member states.

Schedule IV is for highly addictive substances that are rarely used for medical reasons. Schedule I is for substances that are highly addictive or liable to be abused but may have some medical use. Any substance that is schedule IV is also automatically put under schedule I. Schedule II is for those that are less so. Finally, schedule III is for preparation substances intended for medical use with a low likelihood of abuse.

Cannabis was a schedule IV substance until 2020, when it was removed from schedule IV but remained on the schedule I list. Cocaine is also placed under schedule I. Buprenorphine, used to treat opioid use disorder, is a schedule III substance. Ketamine, which is growing in popularity for its medical and recreational effects, is not scheduled after pushback from the WHO. The International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) is tasked with monitoring implementation of the CND’s scheduling decisions around the world.

It’s worth mentioning that unlike other UN bodies that try to establish coordinated positions across the UN system, UNODC has maintained independence in its ideology and operations thanks to strong backing from the United States, China and Russia, which for most of its history have all agreed on a prohibitionist approach to drug policy at home and abroad.

Under President Bill Clinton’s administration in the 1990s, the “tough on crime” mentality ruled the day at the CND. Efforts by the World Health Organization (WHO) to introduce a public health approach to solving problems arising from drug use were actively suppressed.

A breakthrough came in 2016 under President Barack Obama, when the United Nations held a special session on the world drug problem and the UN General Assembly unanimously adopted its outcome document that set forth a new baseline for international drug policy. For UNODC, that meant meaningfully collaborating with the WHO, UN Human Rights Council, UN HIV/AIDS and other programs to bring health, human rights and sustainable development goals into the international drug policy discussion.

The first Trump administration built on those efforts. The United States supported a 2018 UN Human Rights Council resolution asserting that “human rights are an indispensable part of the international legal framework for the design and implementation of drug policy.” The White House also backed the role of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (including eliminating world poverty and hunger, improving access to health and education) in the context of international drug policy.

Those policies mirrored President Donald Trump’s efforts at home. In 2018, his administration signed into law the bipartisan SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act, which acknowledged the need for greater access to treatment for people suffering from opioid use disorder because of a growing realization that traditional indicators of drug policy effectiveness—such as drug seizures and arrests—did not tell the full story. Cannabis was also becoming legal in many US states, softening America’s stance.

Russia, China and others primarily in the Middle East and Asia fiercely opposed the pivot toward a health and human rights approach. Promoters of the new line included primarily the United States, Canada, Europe and Latin American countries such as Colombia, Mexico, Brazil and Uruguay.

The growing divergence came to a head in 2024, when Secretary of State Anthony Blinken attended the 67th CND in 2024, declaring UNODC’s importance as an institution for combatting the spread of synthetic drugs ravaging Americans and people around the world. That year, the United States introduced a resolution that for the first time included the term “harm reduction.” Opposition to the terminology by Russia and China prompted the first vote on a resolution at the CND in decades, which until then had worked exclusively by consensus. A majority of voting members adopted the resolution, marking a pivotal turning point for the acceptance of public health approaches to international drug policy.

It is with that historical context that delegates from around the world came to Vienna this year. However, a better indicator of what was to come were the headlines that dominated the news that week: the US president’s threat to annex Canada and Greenland, his Oval Office dressing down of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, his equivocation on America’s commitment to the mutual defense clause of the NATO treaty. All while warming to Russia’s Vladimir Putin and promising tariffs on allies and rivals alike.

In addition to the opening plenary speech, the new administration’s approach was apparent from day one during the Committee of the Whole (COW), where countries agree language. The United States objected to all mentions of the terms diversity and gender. It also objected to other previously agreed terms such as “stimulant use disorder” as well as listing evidence-based treatments such as contingency management.

The objections represented such a reversal that Russia—whose official government drug policy is “social intolerance,” which encourages people and institutions to mistreat those who use drugs—stepped in to support Western countries rebuking the US-proposed deletion of evidence-based psychosocial treatment for stimulant-use disorder, explaining that it was the CND’s role to specify what interventions the commission supports to promote their use as best practice internationally.

After the United States held up adoption of a paragraph because of the term “alternative development”—which refers to creating other economic opportunities for people in the drug economy—Thailand, a longtime American ally and leader in this space, reminded the US delegation that the language had been developed jointly for over a decade. How could it now be unclear, Thai representatives asked?

When countries are unable to agree on language in the COW, the chair typically requests that delegates negotiate their disputes during “informals,” where they convene behind closed doors to hash out their differences and come back to the COW with agreed language.

While it is common for countries to disagree on text language, the fact that the US delegation was objecting to almost every paragraph this time, including approved language from previous years, was unprecedented.

What was going on?

Unlike Senior Bureau Official Weiland, who had only months of experience serving as a diplomat, the other American delegates he left behind to take part in the talks are seasoned career diplomats. The American chargé d’affaires at the Embassy in Vienna, Howard Solomon, has over 25 years of State Department experience including many tours at UN agencies. The other primary US representative, Virgina Prugh, served as a Judge Advocate in the US Army for 24 years before spending more than a decade in the State Department’s office responsible for engaging with the CND.

However, what became clear to all is that while the career diplomats were the ones forced to raise their hands and face the bewilderment of the world’s delegates, their directions came directly from Washington.

That doesn’t mean that direction from Washington was consistent. One European delegate, who asked to speak off-record, complained that the Americans often reneged on language they’d agreed upon earlier in the day when they’d get contradicting marching orders from Washington as they woke up and started working five hours behind.

In addition to the ideological fanaticism around language, delegates were also confused by a lack of apparent cohesive US strategy or delegates to explain it to them. The American delegation, which usually numbers up to 50, this year was officially 11 but I encountered only five, including a local intern. That’s only one more delegate than in Zimbabwe’s group and 15 less than South Korea’s.

As part of its role as a forum for international discussion, the CND is also a place for countries and civil society to showcase their work through side events. China sponsored multiple presentations on improving precursor detection and law enforcement effectiveness. Brazil sponsored several discussions about the environmental impact of drug production and trafficking on local ecosystems and indigenous populations. Switzerland and Amsterdam sponsored side events on proposed regulations of cocaine. Drug Free World advocates sponsored events on prevention and abstinence-based recovery.

Given State Department official Weiland’s call for action to reduce the 86,882 American overdose deaths last year, and President Trump’s citing of the fentanyl crises to justify imposing tariffs on Canada, Mexico, China and other countries, many hoped for insights into the new administration’s approach at the US’s only sponsored presentation, impressively titled “Synthetic Drugs and Law Enforcement.”

As dozens filled the seats of the largest side-event room, we were met by an empty speaker’s panel. Eventually, the lights were dimmed and a tall man in a suit announced that we would be watching the PBS documentary “7 Days: A Film About the Opioid Crisis in Arkansas.” The irony that the White House was threatening to defund PBS was not lost on participants.

The film is an emotional account of parents losing children and children losing friends. Near the end, an FBI regional director remarks that America can’t arrest its way out of the crisis. After the film concludes, another man came to the microphone to thank people for participating and left as the lights turned off.

Many American civil society delegates expressed embarrassment at their delegation’s lack of effort. The episode reminded me of when my substitute teachers would put on films in school because they were too uninterested to teach.

While it may not be obvious to Americans, many people outside the United States are very aware of the opioid crises crippling our country. Especially those who work in the field of drug policy. The subject is the topic of hundreds of YouTube videos and multiple streaming series on Netflix and other platforms. The US has also been talking about the opioid crisis at the CND for close to two decades.

What remained unclear throughout the conference and after it was the impact of the Washington’s freeze on its contributions to UNODC, INCB and the WHO on international drug policy. UN staff spoke evasively of “funding shortfalls” as rumors swirled.

The United States traditionally provides a fourth of the UN’s total budget and 28 percent of funding for CND and its secretariats. A person familiar with internal conversations, who agreed to speak only off-record, noted that the US had frozen around $80 million—about 80 percent of its annual contribution. Of 50 projects US funding supports, only seven had been assured continuation at that time.

The United States was not alone in scaling back contributions. Germany was also reported to have cut part of its funding as its newly elected national government refocused spending on national industrial policy and defense.

How the freezes and expected cuts will impact the UN’s agency efforts are yet to be fully understood as programs promoting drug prevention, countering human trafficking related to drug smuggling, chemical precursor flows monitoring and more face the chopping block. What is clear is that as the US backs out of the WHO, it will complicate the schedule of new dangerous substances and the rescheduling of less dangerous ones which the WHO plays a critical role in vetting.

The financial machinations helped me realize what I perhaps should have known already: that the American administration’s position appeared to be driven by ideological beliefs that prioritize the upending of institutions rather than any strategic problem-solving. Combined with proposed 50 percent cuts to the US Substance Abuse and Mental health Services Administration that same week (which were later carried out), the developments indicated Trump’s use of combatting fentanyl as an excuse for a tariff war was simply that. Were the White House to want to solve the opioid crisis, it would not be defunding local treatment access and international cooperation simultaneously.

While the new reality took a few days to sink in, by the end of the week, delegates understood they were dealing with not only a different America but a different Trump administration. The fact that Washington had blocked funding prior to the CND also meant it had already lost any potential leverage threatening such cuts could have provided in negotiations.

A European delegate captured the mood saying, “the difficulty is not that America is no longer an ally, it’s that it has become an enemy.” When I asked another European delegate about the change in America’s position, he responded simply “painful.”

Others were more sanguine. A delegate from east Africa told me his country always had to deal with changing US approaches and Washington’s ambivalent approach to his region. His delegation would weather this administration until the next one comes, he said. On the other side of the spectrum, the delegations from Argentina and Russia seemed almost ecstatic to be voting with the US against the others. Members of the Iranian delegation—known for its unwilling to talk to women but boasting pioneering national harm reduction programs at home—for their part were likely bemused to suddenly find themselves voting on the same side as the Europeans after years of antipathy.

But by the end of the week, all delegations appeared to be exasperated by the US’s continued objections. For the Americans were objecting to not only wording in resolutions but also to agenda items and seemingly anything else that happened to include established terms like diversity, gender and sustainable development goals. That meant procedural motions in the plenary session that usually took a few seconds now took several minutes as everything was put to a vote.

On Thursday afternoon, France called off final negotiations on its resolution during the Committee of the Whole, forgoing any other attempt to reach consensus. For the first time in its modern history, the CND delegates went to bed unsure what the final morning would bring.

As the sun rose on Vienna, all delegates from the 53 countries met in the plenary hall. The first item of business was approving Resolution L.3 “Promoting comprehensive, scientific evidence-based and multisectoral national systems of drug use prevention for children and adolescents,” sponsored by Norway. The plenary meeting chair asked for unanimous consent to approve the proposal, which the United States promptly blocked by requesting a vote. The final tally came to all in favor with the exceptions of the US opposing and Argentina abstaining. Why did America vote no? Because the resolution mentioned the Sustainable Development Goals. Argentina blamed the use of the term “gender.”

The morning proceeded in this fashion, with Argentina usually joining the United States against the rest in opposing all resolutions and Iran occasionally abstaining. The resolutions America voted against were: L.3 “Promoting research on scientific evidence-based interventions for the treatment and care of stimulant use disorders,” sponsored by Chile; L.4 “Complementing the United Nations Guiding Principles on Alternative Development,” sponsored by Thailand; L.5 “Safety of officers in dismantling illicit synthetic drug laboratories, in particular those involving synthetic opioids,” sponsored by Poland; and L.7 “Addressing the impacts of illicit drug-related activities on the environment,” sponsored by France.

It was all a preamble to the real show, the Colombia-sponsored resolution L.6 “Strengthening the global drug control system: a path to effective implementation.” The bland name obscured a bold proposal to create an independent panel of 19 experts from around the world and the UN system to review and recommend changes to the entire machinery of international drug policy.

The prohibitionist system that has dominated the past 60 years of international drug policy had failed, Colombia argued. Global drug use is up 20 percent from a decade ago, cocaine production is at record highs, synthetic drugs are flooding global markets, profits from drug trafficking are increasing corruption around the world, and hundreds of thousands of preventable deaths occur every year from overdose and drug use-related diseases like HIV and Hepatitis C.

Besides America’s surprise behavior, the resolution had been the talk of the conference all week as Colombian diplomats negotiated every angle with skeptical member countries. Just last year, such a proposal would have stood no chance of passing. But as the US isolated itself, Colombia and other countries took on leadership roles, and still others became more willing break from conventional alliances. An unofficial estimate shared with me by a civil society group supporting the resolution found the Colombians were short a mere four votes.

In its effort to block the resolution, the US delegation offered an amendment that would have effectively rendered it null. Colombia tried to procedurally block the new amendment, to no avail. As the chair called the votes, tension filled the air. After a few minutes, the chair called out: 12 votes in favor, 25 against, 17 abstentions. Perhaps for the first time ever at the CND, the Americans had been defeated.

Colombia then called on a vote to amend its resolution with negotiated language on which it had worked all week. The room fell quiet as delegates lifted their country placards first in favor, then against, then to abstain. The chair’s voice resonated across the room: 31 votes in favor, eight against, 13 abstentions. The plenary room erupted in applause.

The chair closed the meeting without a final vote on the resolution itself. As delegates grabbed their lunches, some feared the US would use the additional two hours to whip votes.

At 3:15 p.m., delegates returned to their seats and the US representatives called for a vote on the amended Colombian resolution. Country placards went up then down as the secretary called out the names of each in turn. The chair read out the final tally: 30 votes in favor, 3 against, 18 abstentions. The resolution was adopted. The room exploded again in applause that lasted several minutes. The United States had actually lost votes over lunch with only Russia and Argentina standing with it.

As the plenary session came to a close, the American delegates furtively left the room while the Colombian group posed for a victory photo. Even countries opposing the resolution came to offer congratulations. As I sat in a chair taking in the scene, I couldn’t help but feel that I was an unwilling witness to the end of the American-led global order.

In the end, Norway, Brazil, Côte D’Ivoire, the United Kingdom, Belgium, Uruguay, Honduras and the Netherlands cosponsored the Colombian resolution. The intrigue over who will be appointed to the independent panel will no doubt be worthy of an Agatha Christie novel as countries jockey for position. It is far from clear on which side this once-in-a-generation opportunity to either redesign or re-enforce the global drug policy regime will fall. Many countries face surges in far-right parties whose potential impacts on drug policy are unclear at best.

Some, perhaps even many, will not miss America’s leading global role. While Russia sides with the US today, an end of American dominance would advance its long-term strategic longing for more global influence. China, too, is certainly taking note and biding its time. But on that Friday, the winners were none of the big three but a developing coalition of medium-sized countries who see a need for their own strategic autonomy and opportunities for global leadership when collaborating with each other.

The 68th CND tore apart the Vienna consensus and it doesn’t seem like it will be returning anytime soon. That will surely mean a more chaotic process and more divisive debate but, with luck, more democratic outcomes.

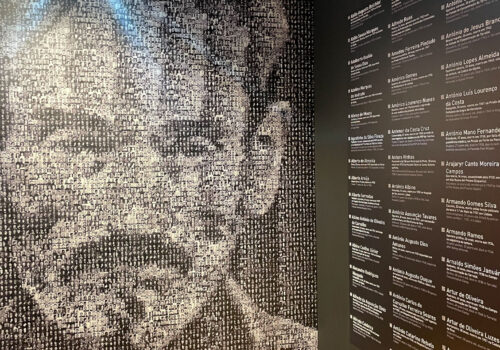

Top photo: Empty Committee of the Whole on Thursday afternoon after final negotiations are called off