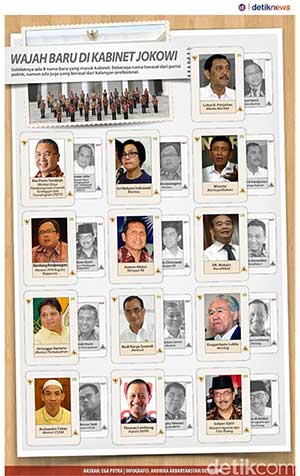

“Every reshuffle brings about better results.” Thus spoke Indonesia’s Vice President, Jusuf Kalla, who may very well find himself being shuffled out of his position in three years’ time. For now, though, he has come up trumps, having just overseen the replacement of twelve (of thirty-six) ministers and the secretary of Indonesia’s Working Cabinet.

If every reshuffle brings about better results, Indonesia’s future is in good hands: President Jokowi and Kalla have reinvented their cabinet twice in less than two years. Nine months after the initial swearing-in ceremony in October 2014, five ministers and the secretary were lost in the shuffle, and now, twenty-one months into their first term, there’s a bunch more swearing (in) going on.

There is ample precedent for this in Indonesia. Former President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY) reshuffled his cabinet five times[1] in his two-term, ten-year stint as the first directly elected representative of Indonesia’s people. (Coincidentally, Kalla was his vice president as well.) But Jokowi-Kalla have doubled the pace of change, leaving us to wonder why things need to be shaken up so frequently, and to what extent this annual reshuffling is disrupting the machinations of the State. Sure, every reshuffle brings about better results…but for whom?

Playing His Cards Right

“The spirit of the Working Cabinet reshuffle is to strengthen the government’s work performance, in which all Cabinet members can work in a team that is solid and unified,” President Jokowi explained. Strength does seem to be what he is after, though perhaps not only for the cabinet. Three changes in particular warrant consideration.

First, a three-way trade was made. In order for SBY’s Finance Minister, Sri Mulyani Indrawati, to resign her position as Managing Director of the World Bank and return to her former position, Bambang Brodjonegoro had to move over to Minister of National Development Planning, which necessitated that Sofyan Djalil uproot and replant himself as Minister of Land and Spatial Planning. Sri Mulyani was ranked by Forbes magazine as the 38th-most powerful woman in the world, and she is quite popular among Indonesians, so this change has been chalked up as a win by most of my Indonesian friends.

People have looked less favorably, however, upon the appointment of Wiranto as Coordinating Minister for Political, Legal, and Security Affairs. In 1999, he oversaw the military incursion into the area now known as East Timor. As detailed by ICWA Fellow Curt Gabrielson (CG-1), two decades of occupation by Indonesia’s military resulted in the death of over 800,000 people on that island, half of which is still controlled by Indonesia. The United Nations and human rights groups contend that more than 2,000 East Timorese were killed and 500,000 more were forced into displacement under Wiranto’s watchful eye.[2] Indonesia’s own Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) considered Wiranto’s appointment to this position back in 2014 to be “problematic,” but the “spirit of the Working Coalition” is not as concerned with the spirits of the East Timorese these days. There are grave implications to the notion that Wiranto is again helping “strengthen the government’s work performance,” as ha has a tendency to overplay his hand.

Surprisingly, the skeletons in Wiranto’s closet have gone mostly unmentioned amid the outcry over the appointment of Archandra Tahar as Minister of Energy and Mineral Resources. His sin? After twenty days on the job, it was discovered that the former president of American company Petroneering, who left behind a six-figure salary to serve his country, holds an American passport.[3] A vocal contingent of Indonesians made no bones about their belief that his citizenship status should disqualify him from serving, which makes the silence about Wiranto’s human rights record that much more deafening. (Ignasius Jonan was selected as Minister instead, and Tahar was named as his Vice Minister. Curiously enough, this did not prove problematic.) It bears noting that only ten months prior, President Jokowi had encouraged the adoption of dual citizenship.[4] Had he played that differently, this whole kerfuffle might have been rendered moot.

As my focus is on education, I’ll briefly note one other change that came as a surprise to many, and which I intend to expound upon in my next Newsletter.

After only twenty months on the job, Anies Baswedan was abruptly reshuffled out of his position as Minister of Education and Culture in July of this year. Just after being sworn in, the man who Forbes magazine listed as one of the world’s top 100 public intellectuals published thirty-four specific short-, medium-, and long-range goals[5] for Indonesian education. Twenty months is not enough time to achieve thirty-four goals, but most would agree that progress was evident.

According to Ali Munhanif, the head of the Center for Public Policy Studies at the National Islamic University of Jakarta, Baswedan’s removal was necessary because his “vision deviated slightly from the vision and the mission of the President.” Conversely, Baswedan’s replacement, Muhadjir Effendy, told reporters he “has no ministerial mission or vision,” because “there is only the vision and mission of the President.”[6]

If President Jokowi stacked the deck by intentionally selecting an educational minister who would take no initiative and simply do as told, this would amount to a hypercentralization of political power, in which a single person – Jokowi himself – will set education policy for 250 million people. And it sure doesn’t seem like he’d have much trouble forcing Effendy’s hand.

Since rising to his new position, the new minister has only exacerbated these concerns. On the day he was sworn in, Effendy said in an interview that he had never imagined he might become a minister until the day before. In that same interview, he recounted that he originally wanted to be a middle school teacher, but had been rejected; headlines the next day read, “Muhadjir becomes Minister of Education even though he failed to become a teacher.”[7] ‡ It is not hard to believe that he really doesn’t have any mission or vision whatsoever. Was this, along with Effendy’s affiliation with Muhammadiyah (one of Indonesia’s two largest Islamic groups), what President Jokowi was seeking? For the sake of Indonesian education, I wish he’d lay his cards on the table.

‡ In truth, that newspaper headline was a bit misleading – Effendy actually passed the test, but was not selected because he had no previous teaching experience. A graduate of one of Indonesia’s most renowned teacher preparation programs at the National University of Malang. Effendy returned to academia after this setback, obtained his Master’s degree in Public Administration from another of Indonesia’s highest-ranked universities, Gadjah Mada, then continued on to a doctoral program at Airlangga University. Only after obtaining his Ph.D. in Military Sociology did he get his first teaching job – as a professor back at his undergraduate university. Over the next few years, while teaching pre-service teachers at the University of Malang, he also lectured at another nearby university. It was this side job that has paved the path to his ministerial position – in 2000, he became the Rector of Muhammadiyah University of Malang, plugging him in to one of the most extensive politico-religious networks in the country. Still, for all of these accolades, he was relatively unknown as of July 25th, 2016. To date, Muhadjir Effendy remains something of a wild card.

[1] https://m.tempo.co/read/news/2013/04/11/078472712/sby-5-kali-reshuffle-kabinet-indonesia-bersatu

[2] http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2016/07/27/wiranto-replaces-luhut-as-security-minister.html

[3] https://news.detik.com/berita/3274572/isu-menteri-esdm-archandra-tahar-pegang-paspor-amerika-serikat-ramai-dibahas

[4] http://news.okezone.com/read/2015/10/26/337/1238055/di-as-jokowi-janji-dorong-penerapan-kewarganegaraan-ganda

[5] https://www.quora.com/How-successful-was-Anies-Baswedans-term-as-Minister-of-Education-What-are-the-key-programs-and-succeses

[6] http://nasional.kompas.com/read/2016/08/06/19320281/diganti-anies-baswedan-dinilai-sedikit-melenceng-dari-visi-presiden

[7] https://m.tempo.co/read/news/2016/07/28/058791321/kisah-muhadjir-gagal-jadi-guru-malah-jadi-menteri-pendidikan