I presented this paper, originally entitled “Alterative Origins of Arab Comics,” at the second annual Cairo Comix Festival on October 4, 2016, hosted at the American University in Cairo. It was part of a seminar day devoted to comics scholarship, including presentations from the British critic Paul Gravett and the French critic Jean-Pierre Mercier. The festival also featured three evening salons, which convened discussions among comic artists from Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Iraq, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia, and more.

In Arabic, we call them rasam komiks or fanan komiks—which literally translates into English as the one who draws comics or comic artists. Of course they are artists, too.

American and European scholarship and criticism has explored the rich, complex, and sometimes conflicted relationship between art and comics. In Egypt, state institutions and publishing houses have profoundly separated these two fields—fine art and graphic narratives exist in separate orbits, separate sections of the bookstore, separate frames of mind. Today, I want to begin a discussion that looks at what connects art and comics in Egypt and the Middle East.

This is not an attempt to redeem comics from its position as a low or pulp art—I like that it’s a low art!—but rather to offer a provocation for us as artists, scholars, critics, and students of comics to think beyond strict definitions. I think that opening the door to modern and cotemporary art in this seminar on Arab comic art will be beneficial for the practitioners among us—that is, the comic artists—and it will also show the continuity between underground artists today and yesterday.

First, I’ll quickly review the conventional history of Egyptian and Arab comic art; then I’ll explain where the idea for this paper stemmed from, after which I’ll review three prominent artists whose practice blurs the boundaries of comics and art. Here, I want to be clear, that I am not arguing that these artists are comic artists, but rather that a study of their work can deeper our own understanding of comic art.

Upfront, let’s review some history. At this point, the origin story of Arab comics is relatively well known. A version of that origin story consists of karikatur—political cartoons, a precursor to comics—and it begins with Yaacub Sannu in Cairo in the 1880’s, where his periodical Abu Naddara (which translates roughly as “The Man with the Glasses”) and later spin-offs lambasted the khedive in drawings and satirical texts, as well as short plays. Meanwhile, across the sea, Ottoman publications, influenced by French and British caricature, took off in Istanbul and traveled with the waves of people in the empire, taking aim at those in power. The art of Sannu’s caricatures, Ottoman works, and contemporaneous drawings in Europe are strikingly similar.

In the 1920’s in Cairo—with the emergence of a string of popular glossy magazines, some in color, most with photographs—cartoons, comics, and caricature began to fill the pages of the elite reading list. (It seems similar trends were happening in Beirut—we would have to cross check with Baghdad and Damascus). Caricatures were on covers of magazines every week, inside the pages, and whole new humor publications sprouted up, following the humor style of the New Yorker, mocking the upper echelon of society and so forth. By the 50’s and 60’s, these forms were adapted for children, taking a cue from Western comics and also local storytelling traditions.

It isn’t until five decades later, at the beginning of the 21st century, that artists began re-appropriating the art of caricature for adults. Or is it? I would like to propose an alternative origin of Arabic comics.

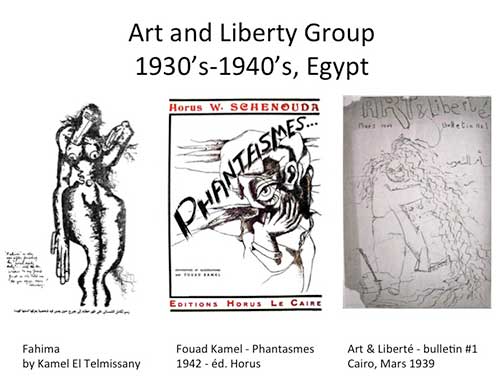

Last November, at a conference hosted by American University in Cairo and Cornell University entitled “Egyptian Surrealists in Global Perspective,” I was struck by the similarities between today’s comic art and a group of artists from the 1930s and 40’s known as the Art and Liberty Group. Some of you might have attended the opening earlier this week at the Palace Des Arts of some of this group’s work—they are often called Egyptian surrealists—a group of radical and experimental writers and painters who sparked new approaches to modern art in the country.

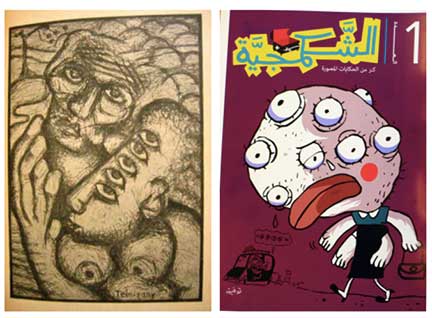

That there are shared motifs and imagery between the Art and Liberty group and the contemporary Egyptian comic zine Tok Tok, between artists from a long time back and those of today, made me wonder more broadly about the relationship between comics and art. The rough pen strokes of Kamel El-Telmissany (1915-1972) and the raw stories contained within the drawings of his surrealist colleagues represent predecessors to the long-form comics currently being published in Egypt, Lebanon, Morocco, and Tunisia. We see similar grittiness in illustrations from his colleagues, notably Fouad Kamel (1919-1973), in the Arabic-language publication Al-Tatawur and in exhibition catalogs from 1938-1948.

Comics, as you all know, are a hybrid form—borrowing from other media, of course satire and storytelling and art, but also further afield. Comic artists sometimes act as social critics, other times as journalists, and often strictly as artists.

After spending years researching the history of comic art in newspaper archives, booksellers’ stalls, and in interviews with cartoonists, I realized that perhaps I needed to widen my purview to include, for example, the pamphlets and bulletins of Art and Liberty Group. Their lines are often simple yet communicate irreverence and playfulness that paved the way for the distorted visions of reality, seen in the works of the prominent Egyptian cartoonist Ahmed Hegazi (1936-2011) in the 70’s and of some of Tok Tok’s artists today.

Modern art and caricature have always had a rich and dynamic relationship in Egypt, since both forms took off in the early 20th century. At times it seems that the cultural gatekeepers of Cairo have taken great pains to separate the realm of art from that of cartoons and comics—the latter sequential or satirical forms derided as low art. And yet caricature has always been a fundamental quotient of modern art, something even seen in the work of Mohamed Mokhtar (1891-1934), the great sculptor who shaped the trajectory of Egyptian modern art, yet performed the same task as the caricaturist in simplifying the likeness of his subjects.

Many pivotal, pioneering “comic artists” were actually fine artists, too. Husein Bicar (1913-2002), a painter who founded the seminal Egyptian children’s magazine Sindibad in 1952, comes to mind. Or consider Adham Wanly (1908-1959), a renowned Alexandrian who also drew caricatures for the popular magazine Roz El-Yusef. Many other fine artists have tried their hand at caricature, and today I want to reflect on not just how fine art affects comics, but how comic strips have affected fine art.

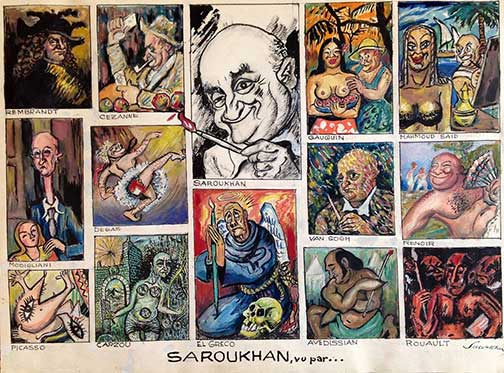

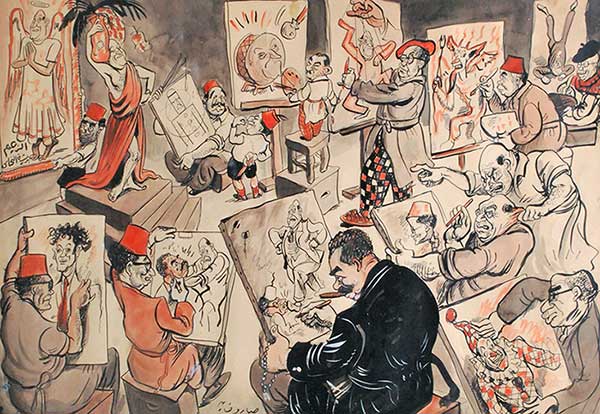

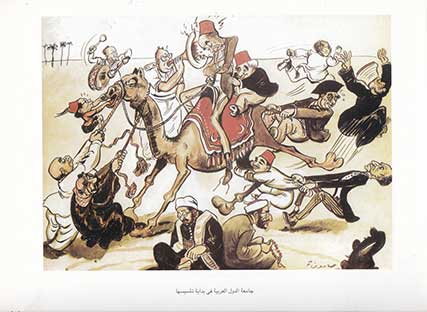

Let’s consider a recent show at a gallery of cartoon canvases by a classically trained artist who went to into caricature: Alexander Saroukhan (1898-1977). His cartoons appeared in the top newspapers and magazines, from the 1930’s onwards. His work has many of the hallmarks of that era: the pashas, the loaded symbolic meanings, the gag jokes, the recurring characters—some of that he even invented, like Egypt’s famous everyman “Al-Masri Effendi.” But, unlike many of the cartoonists at the time, Saroukhan uses each frame to tell a long, windy and sometimes complete story. His cartoon entitled “The Founding of the Arab League,” for instance, is more comic—that is sequential—than other cartoons of that time. In his single frame works, we see him anticipating the sequential narratives of later generations. Each of his illustrations feature whole worlds of politics, filled with casts of significant characters, fodder for students of modern Egyptian history and eye-candy for art critics and casual observers alike.

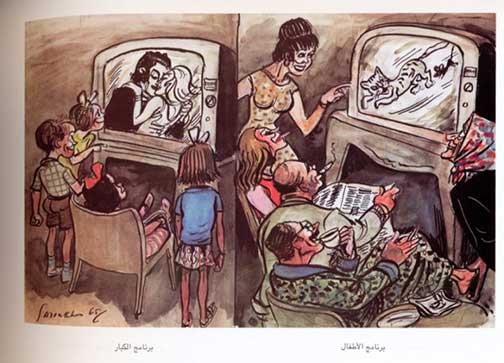

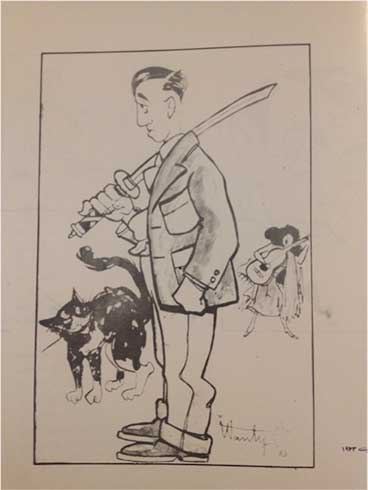

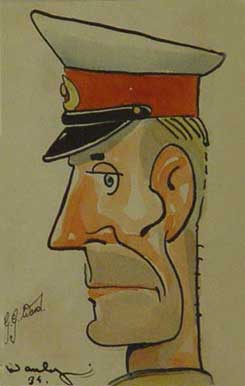

Now if Saroukhan is better known for his caricature than his art, we might say the opposite about Adham Wanly (1908-1959), half of the famous Wanly brothers from Alexandria who were of a piece with the emergence of modern art in Egypt. Indeed both Seif and Adham painted scenes of modernity: the ballet and ball, musicians, nudes, writers, the circus, and many more exuberant colorful milieus.

Walking through a small museum dedicated to the Brothers Wanly in Alexandria, I wondered: What did Adham Wanly’s caricatures do differently from his paintings? How did caricature affect his painting? Unfortunately little research has been done on Wanly’s caricatures. The books about Adham and his brother only mention in passing that the former drew caricatures. The Egyptian Ministry of Culture has hundreds of his drawings in storerooms and only a handful of them on display. And yet the more I look at his work, I see that there is a very thin line that separates his caricature and his paintings: both types of practice contain exaggeration, humor, and movement.

If Adham Wanly’s relationship to illustrations is relatively straightforward—after all, he was a newspaperman at the beginning of his career—the work of another artist challenges our presuppositions about comics and gives us cause to rethink the origin of Arabic comics. I am speaking of Abdel Hadi Al-Gazzar (1925-1965), another one of Egypt’s great painters and modern artists.

Gazzar is known for his colorful expressions of social realism and dystopian visions of anti-social surrealism; his depiction of folk life and mysticism inspired from his upbringing in the Cairo neighborhood of Sayeda Zeinab. (Gazzar is also associated with the Art and Liberty Group.)

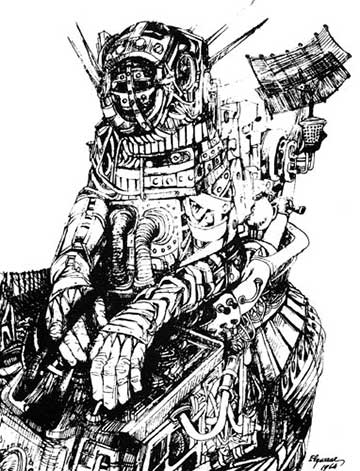

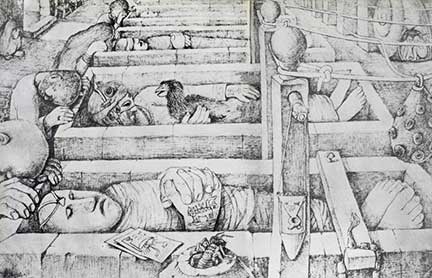

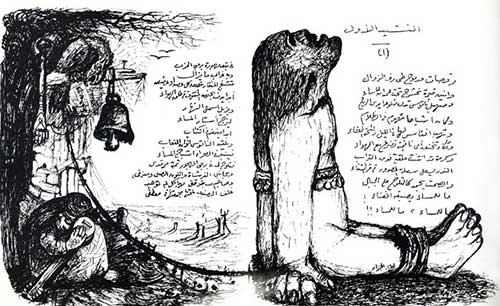

What if I were to tell you that his work also has some of the trappings of comic art? At a small gallery on display at Cairo’s Modern Art Museum in January, I was taken by Gazzar’s pencil and ink drawings, an aspect of his practice that has not received as much attention as his canvases. Gazzar’s pen strokes project intense movement and stillness, techniques sometimes seen in comic art. Indeed some of Gazzar’s grotesques would not be out of place in contemporary zines or graphic novels. His characters are fantastical expressions of anxiety regarding technological advancement that would work well in a Philip K. Dick novel. In other more mystical works, Gazzar incorporates cryptic lyrics of poetry, or sometimes uses his pen to draw over a finished painting, adding jagged characters in the margins.

Also of note: Gazzar illustrated a series of poems, including many by Ahmed Morsi. The result is a turbulent page that, for this reader, can be neatly described as the proto-alt-comic or a graphic poem. These are not comics, of course, but they contain many of the elements of comics: the mixing of words and images (as well as the dissonance between words and images), recurring characters, and the aesthetic qualities of a sketchbook. For Gazzar, his ink drawings were some of his strongest works. To my mind, these ink drawings have more in common with some of the alternative comics emerging from the Middle East today than the silly children’s magazines that appeared in the 1950s.

* * * *

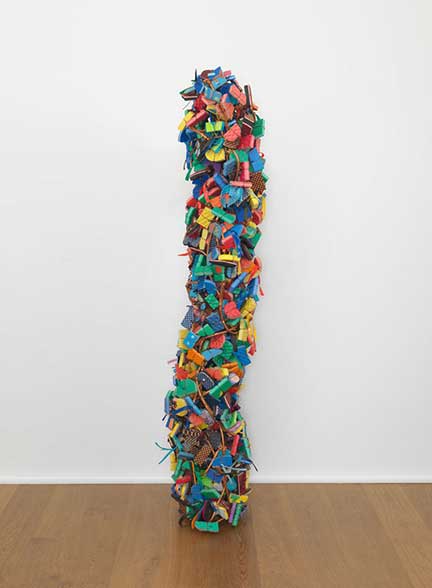

That brings us to a more contemporary example. Earlier this month, the pioneering Emirati artist Hassan Sharif passed away. Sharif (1951-2016) is best known for conceptual works, which have been acquired by museums such as the Guggenheim and Pompidou. From afar, some of his installations look like heaps of rubbish; others look strangely natural, like bright coral reefs trapped in the white cube. Up close, they are intricate arrangements of flip-flops or cotton, wood or wool—to name a few. His works comment on consumer culture and whimsically express how mass-produced objects are at once ephemeral and essential components of our everyday life.

Should we be surprised that the abstractionist began his career as a political cartoonist?

Prior to studying and experimenting with fine art, Sharif drew one-panel cartoons for the weekly newspaper Akhbar Dubai. From 1970 to 1979, he produced thousands of such illustrations, tackling events of the moment, whether sporting news or the Camp David Accords. (Unfortunately, only a few of them are available online.)

At first glance, these two aspects of his practice—abstract installations and gag cartoons—appear to be irreconcilable. Yet there is, as he noted in an interview, “a strong bond” between these two approaches; he said that “traces of caricature” are present in his objects. “Traces of Caricature,” is an apt starting point for thinking through Sharif’s work, as well as that of Gazzar and Wanly.

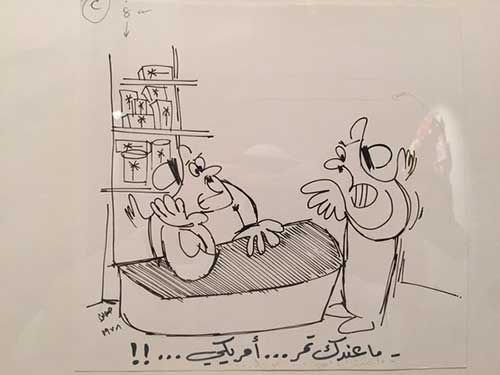

Looking at Sharif’s varied works, we can begin to consider what the conceptual and the cartoon have in common. Through his simple cartoon lines, we experience the rumblings of irreversible change. And with that comes anxiety. Consider the cartoon, in which a man walks into a shop to purchase dates. But not any old dates. He seeks American dates. Is the local product not good enough? Or will dried fruit from California evoke a higher status? Whatever the reason, the look on the shopper’s face is anxious, teeth grinding together: acquiring the correct product is the imperative.

This small sample of caricatures offers a stinging indictment of consumerism, a perspective also articulated in his installations and objects. Sharif, in a 2014 interview, described his objects “as more ironic than any caricature that I did in the ‘70s.” In this way, he extracted the essence of gag humor and injected it into another media.

Sharif never returned to cartooning, but his writings from recent years illustrate enduring concern about consumerism and technology. “How can today’s human verify his existence without at least sending one SMS a day?” he asked in the essay “The Age of Consumerism.”

Importantly, his cartoons document the origins of the Emirates. Skyscrapers rise, and islands appear out of the blue. The only thing grinding the city to a halt is bumper-to-bumper traffic.

With prescient views of commercialization, Sharif’s editorial cartoons would not seem out of place in today’s papers. “I am not inspired to draw any new ones, as the ones drawn decades ago still apply today,” he told The National in 2011. “The same tyrants are refusing to leave their thrones, and the youth are still dreaming of a nation they can be proud of and have a say in.” In Sharif’s case, cartoons and conceptual art are deeply intertwined.

* * * *

So what is the relationship between art and comics, between comics and art? Why have so many fine artists experimented with caricature and cartooning?

It’s not just Roy Lichtenstein or Jeff Koons who have re-appropriated comic imagery—Arab fine artists are doing the same, which forces us to reevaluate these boundaries. Perhaps there is a something more fundamental about the relationship between comics and art—the fact that so often sketches and sketchbooks have strong connections to comics, the fact that all canvases tell stories, and comics in a way unwind and open up these stories.

This is not to say that we need to start treating Arab comic art as a highfalutin field — that we want the comic strips and caricatures of the past and present to be hung up in stuffy museums. Rather, we need to conceptualize a symbiotic relationship between art and comics, one that allows for the sharing and interchange of ideas apparent in many of the works I have shown you today.

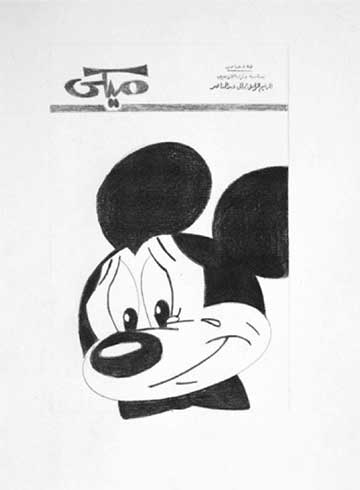

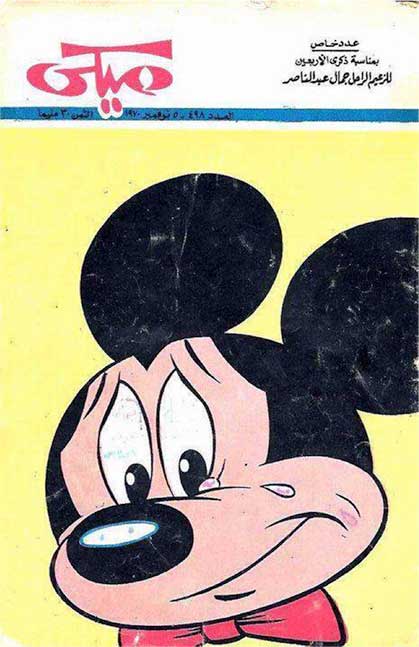

This drawing by the Amman-based artist Ala Younis, which was exhibited at Gypsum Gallery in Garden City, offers a new way of considering the relationship between comics and art. Younis took a famous cover of the children’s comic magazine Mickey—one of Mickey mourning Nasser’s death—and re-drew it in pencil. As a graphite depiction of a mass-media publication, it’s no longer a straightforward comic cover. When a Mickey comic is reproduced in pencil, his meaning changes, he becomes something different. But wait, is this portrait of Mickey art? Does that mean that the original cover was art too? To see a Mickey cover, drawn impeccably by hand and hanging in a top art gallery—this experience pushes the reader to think through the very definitions of art and comic art. This drawing was part of Younis’s project, UAR or the United Arab Republic, in which she explored the history and cult of personality surrounding Nasser and other Arab nationalists. It’s worth noting, too, that artists are increasingly conducting intense research into their subjects—archival work, interviews, etc.—operating much in the same way that caricaturists or comic journalists, do. Again, the lines converge.

Something similar is happening in the work of the contemporary Egyptian artist Mohamed Abla: his series of collage-like paintings incorporates famous Egyptian caricatures as well as images from newspapers. (It is no coincidence that Abla has established the Caricature Museum in Fayoum, Egypt.) Abla is mindful of his borrowing from pop culture imagery, yet his work is notable in the way it integrates of these forms directly into the work, a sort of pre-photoshop photoshop.

These are very clear examples of literal comic imagery entering the canvas, but of course the relationship between art and comics is more complex than borrowing and sharing.

We can think of dozens more examples locally and regionally—the contemporary gallery Townhouse often hosting Tok Tok openings, the Lebanese artist Mazen Kerbaj showing his work at contemporary galleries in Beirut and beyond, the Iranian animator Ali Akbar Sadeghi exhibiting at Art Dubai Modern, etc.

I could go on and on, finding links between recent comic publications and fine art—but for now I wanted to pose a bigger question: should we look beyond the pages of comics and caricature to better understand the emergence of comic art in Egypt and across the Middle East?

Rather than rescue comics from their current stature as a low art, let’s do something else entirely. Let’s rescue the artists Gazzar, Sharif, and Wanly from the museum and use them to celebrate the power of the pen.