BEIRUT — Rana Dirani used to run one of the largest Arabic language schools in the Middle East. The Saifi Institute, which she founded in 2008, hosted roughly 200 students for every five-week term. Dirani devoted herself to building a community for the young people from outside the Arab world who flocked to her school: As the program expanded, she opened a hostel and a café in the same cluster of pastel-colored buildings overlooking the Mediterranean.

Today, the Saifi Institute lies in rubble. All that remains is a piece of artwork carrying an inscription: “I speak Arabic like a nightingale.” One teacher had been standing in front of a window when the Aug. 4 port explosion tore the building apart—he suffered over 60 cuts and injuries across his body, and lost partial sight in one eye.

But the destruction was only the beginning of Dirani’s struggles. Still reeling from a head injury and with her apartment and business in ruins, she was treated like a criminal by the same state whose negligence led to the blast in the first place.

In the days following the explosion, she and her father hired workers to help dig through the rubble to salvage whatever they could—with the lira currency having lost over five times its value against the dollar in less than a year, importing new equipment for the institute from abroad was impossible. As they prepared to begin their work, the police came and started to arrest the workers. They would later release a statement saying the action was due to a government regulation prohibiting entry into buildings in danger of collapse, although Dirani’s team had planned to enter a building where the damage was less severe.

When Dirani’s 75-year old father protested, the police twisted his arm behind his back and prepared to arrest him as well. In a video of the incident that went viral on social media, Dirani is frantic, screaming that her father’s shoulder had already been dislocated in the blast. “You have no right!” she yells.

That was only the beginning. Dirani herself was later hauled into the police station herself by officers furious that her video had gone viral. “Their second question was: ‘How many followers on Facebook do you have?’” she told me. “‘We have been trying to clean up the image of the police in the area, and you came and fucked it up.’”

“I said, ‘I fucked up your image in front of the people? It’s known how bad you are.”

As the situation escalated, Dirani’s father, brother and ex-husband were all arrested. Eager to salvage their reputation, the police first demanded that Dirani film a video apology as a condition for dropping the charges against them. When she refused, they settled for a written statement, which they drafted themselves. In the text, Dirani apologizes for a “misunderstanding” and any negative statements toward the security forces, “which stood by our side from the very first moment of the explosion.”

Meanwhile, two months after the Aug. 4 port explosion, the deterioration of affected Beirut neighborhoods is only accelerating. The blast killed over 200 people, injured thousands more and caused up to $15 billion in economic damage. Those wounds are bad enough but have also been accompanied by a further collapse in trust in the state to protect residents’ lives and livelihoods.

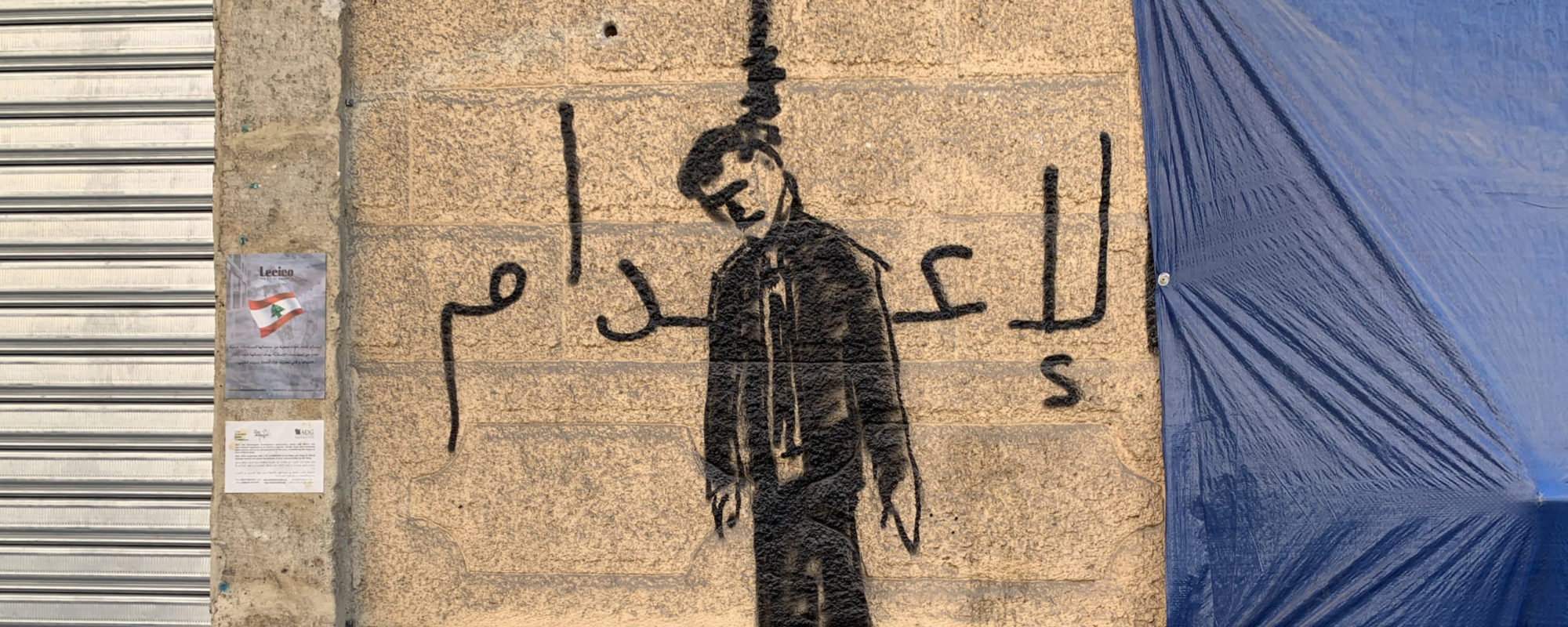

These are also the parts of Beirut that I call home. My wife and I live in Mar Mikhail, a predominantly Armenian neighborhood on the eastern edge of the city. The anger here is palpable: “Execution,” reads one piece of graffiti beside a picture of a man hanging by a noose. The death notice of one young man, wearing a tuxedo and smiling in the poster, rails against the narrative that his sacrifice somehow served a larger cause: “He is a victim and not a martyr.”

Residents are also growing further impoverished. A survey of the affected areas by a Lebanese NGO found that less than a third of residents are earning more than the minimum wage of 675,000 Lebanese lira per month, now equivalent to roughly $80. More than half of residents described security in the area as “bad”—a finding borne out by soaring country-wide crime rates. Murders have doubled and car thefts have jumped 50 percent since last year as people have grown increasingly desperate.

The pace of reconstruction has been glacial. Shards of glass remain embedded like tiny pieces of shrapnel in the walls of our apartment, and broken wooden chairs and a dining table are piled in a corner of the living room. But we are the lucky ones: The Syrian refugee family living in a dilapidated building across the street and the nearby Armenian car mechanic have not yet been able to repair the windows of their homes even as Beirut nears its rainy season.

Shards of glass remain embedded like tiny pieces of shrapnel in the walls of our apartment, and broken wooden chairs and a dining table are piled in a corner of the living room. But we are the lucky ones.

Besides its large Armenian community, our bustling neighborhood is home to Syrians and other transplants who arrived looking for work or refuge, as well as Lebanese and American yuppies drawn to the bohemian bar and café scene. But truth be told, it suffered from tensions that long predate the current crisis. One Muslim friend seethed that her Christian neighbors still treat her like an unwanted intruder decades after she moved here. At one point, a Syrian man was caught puncturing the tires of cars in the area—he was being paid by a nearby mechanic who hoped to profit from the repairs. The Syrian family across the street, which had nothing to do with the incident, was nevertheless forced to temporarily leave home until tempers in the area cooled.

It would be a mistake to assume that the current crisis will lead the area’s residents to unite around their shared anger at the state’s failures. The opposite is more likely: As the state collapses, people are increasingly liable to retreat to their ethnic or religious communities and rely on the dominant political parties that pose as their protectors. “Impoverishment typically throws people in the hands of particular sectarian groups who can support them,” said Mona Fawaz, a professor of Urban Studies and Planning at the American University of Beirut.

She sees the seeds of this dynamic in legislation passed by parliament on Sept. 30 that placed a freeze on the sale of property in the area. While advocates for the law describe the provision as a way to prevent property speculators from preying on residents in their moment of weakness, Fawaz believes it echoes previous attempts by Christian lawmakers to prevent the sale of land to Muslims.

Nicolas Sehnaoui, a parliamentarian from Beirut who helped draft the legislation, readily admits that he’s interested in protecting the area’s Christian identity. He describes Christians as the “weak link” in Lebanon’s social fabric, more liable than others to respond to the country’s economic and political crises by escaping abroad. Freezing property sales, he said, was a step to prevent “this Christian part of the city suddenly changing demographically.”

But as the state focuses on the demographic makeup of the area, it has done precious little to help residents rebuild. Sehnaoui sounded pessimistic about the capacity of the state, and didn’t even pretend to present a comprehensive reconstruction strategy: The most the government could do, he said, was conduct repairs on homes with minor damage. Buildings that were completely destroyed—along with schools, hospitals and the port itself—would have to wait for international aid, and it is unclear when or if that will arrive. In a sign of the state’s inability to meet the magnitude of the moment, the new law also allocated a mere 1.5 billion lira, the equivalent of less than $200,000, to reconstruction. But that still didn’t mean even this meager sum would be disbursed, Sehnaoui said, “because the treasury has no funds.”

The truth is that the prospect of returning my neighborhood to what it had been prior to the explosion is a pipe dream. The old status quo was already untenable: “We know that displacement preceded the blast,” Fawaz said, as residents fled the area’s high prices. Even before Aug. 4, many of the high-end residential buildings in the area sat empty. Those buildings were built when the dollar was at 1,500 lira, and the price of repairing them is now prohibitively high. “Now that we realize, all of us, that we were living in la-la land, we can’t fix them,” Fawaz said.

Not everyone is ready to give in to despair, however. A café named Kalei remains nestled in a quiet corner of Mar Mikhail, a bit of green amid the construction and broken glass outside. It has struggled to stay open: The prices of coffee imports have skyrocketed even as customers’ salaries remain the same, making it impossible to raise prices. The blast caused tens of thousands of dollars in damages, and led many of the core staff to leave the country. “The thought of just not getting the shop fixed crossed my mind, I would be lying if I didn’t say that,” co-owner Dalia Jaffal, a young Lebanese who previously worked in agricultural consulting in Kenya, said. “It’s natural after such a big thing, to just not want to invest any more—personally, emotionally, financially.”

The café is not really about making money for Jaffal. She considers her 25 employees like a family, and speaks with pride about how they have built a place where both staff and patrons feel welcome. What would happen to all those people if she were to shut down? Staying open enables her to keep a more optimistic vision of the country alive despite the powerful forces arrayed against her.

“In a country like Lebanon, where your vote means nothing, this business is my way of voting for the things I want to see happen.”

A version of this dispatch also appeared in Slate: Read here