DARRANG, India — We drove three hours and a hundred miles past green hills and acres of rural farmland before finally pulling over into a dusty parking lot by an empty roadside tea stall. We were somewhere along the Gerukbari national highway, a winding road that cuts right through the middle of Bongaigaon and Chirang, two sprawling districts in the northeastern state of Assam. I’d come here from the capital city Guwahati to meet a man named Nanda Ghosh, who works for a non-profit called Citizens for Justice and Peace. In the last few years, the 30-year-old has traveled to every corner of the state, searching for people who have found themselves suddenly mired in a Kafkaesque system of accusations, trials and imprisonment over their citizenship.

Encircled by the gushing waters of the serpentine Brahmaputra River, the state is ordinarily known for its tea and rhino conservation, but, in recent years, Assam has set the stage for an ongoing litmus test for who is considered an Indian citizen. A flow of migrants moving across porous borders shared with Bangladesh, Myanmar and Bhutan have led to a chasm between “native” Assamese people and outsiders from neighboring countries. The divide widened in 2019, when the state government updated a formal registry of citizens and India passed a nationwide citizenship law.

In the last month of my fellowship, I hoped to understand the collateral damage of such legal measures through Ghosh. Arriving at the parking lot in a white Jeep, he quickly stepped out to greet me. He was short and sported a mustache, and his leather jacket contributed to an air of authority that matched his pensive demeanor.

“You can tell your driver to wait here,” he said. “We’ll go in my Jeep.”

We were heading 20 miles east to a small, sleepy village named Ekrabari in the rural district of Darrang. On the road, Ghosh explained the reason he didn’t ask Deepan, my driver, to follow us: He belongs to the dominant Assamese community. “You never know when tensions might flare,” he said.

That would have sounded presumptuous were it not for Assam’s checkered history of communal tensions. The state’s wariness of accepting migrants stems from India’s British colonial era, when farmers and migrant laborers from neighboring West Bengal were encouraged to settle in Assam to work on British tea plantations. To the Assamese community, a mix of Southeast Asian descendants and upper-caste Hindus who migrated to Assam in the 1300s, the Bengalis’ arrival felt like an assault on their culture, particularly when the British imposed Bengali as the official language.

In 1947, another mass exodus of Bengali Hindu refugees from Bangladesh, followed by East Pakistan, occurred when British India split into independent India and Pakistan. It led to the creation of the “Assamese movement,” a popular anti-immigrant uprising that swelled to its biggest size in 1983, when at least 2,000 Bengali Muslim villagers were massacred over six hours in the paddy fields of a town called Nellie. The government subsequently issued the Assam Accord, promising to identify and deport all those who had crossed the Indian border after midnight on March 24, 1971, when Bangladesh became independent.

Today, the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party—which fears that Hindus will become a religious minority because of the growing Muslim presence—sees a convergence between its interests and those of many Assamese speakers in keeping Bengali Muslims out of Assam. In 2018, the government launched a National Register of Citizens (NRC), designed to be a definitive record of citizenship in the state. The official registry excluded close to 1.9 million people—six percent of the state’s population of 30 million—who failed to prove their Indian origin. Before the final list was published in July 2019, tens of thousands had already been declared illegal migrants by Assam’s foreigners’ tribunals—quasi-judicial bodies established in 1964 tasked with ascertaining who is a foreigner—as well as the state’s election commission, which examines old voter records to mark those deemed to be “doubtful” voters and hands them over to border police.

The NRC shifted the burden of proof to those declared foreigners, who must now plead their cases at a foreigners’ tribunal to prove that either they or their parents were born in Assam before 1971. Those who lose their cases face another obstacle: In recent years, Bangladesh has refused to accept Assam’s mass of newly rejected Bengalis as its citizens, rendering them effectively stateless. Unwanted by India and Bangladesh, they are kept in detention indefinitely.

* * *

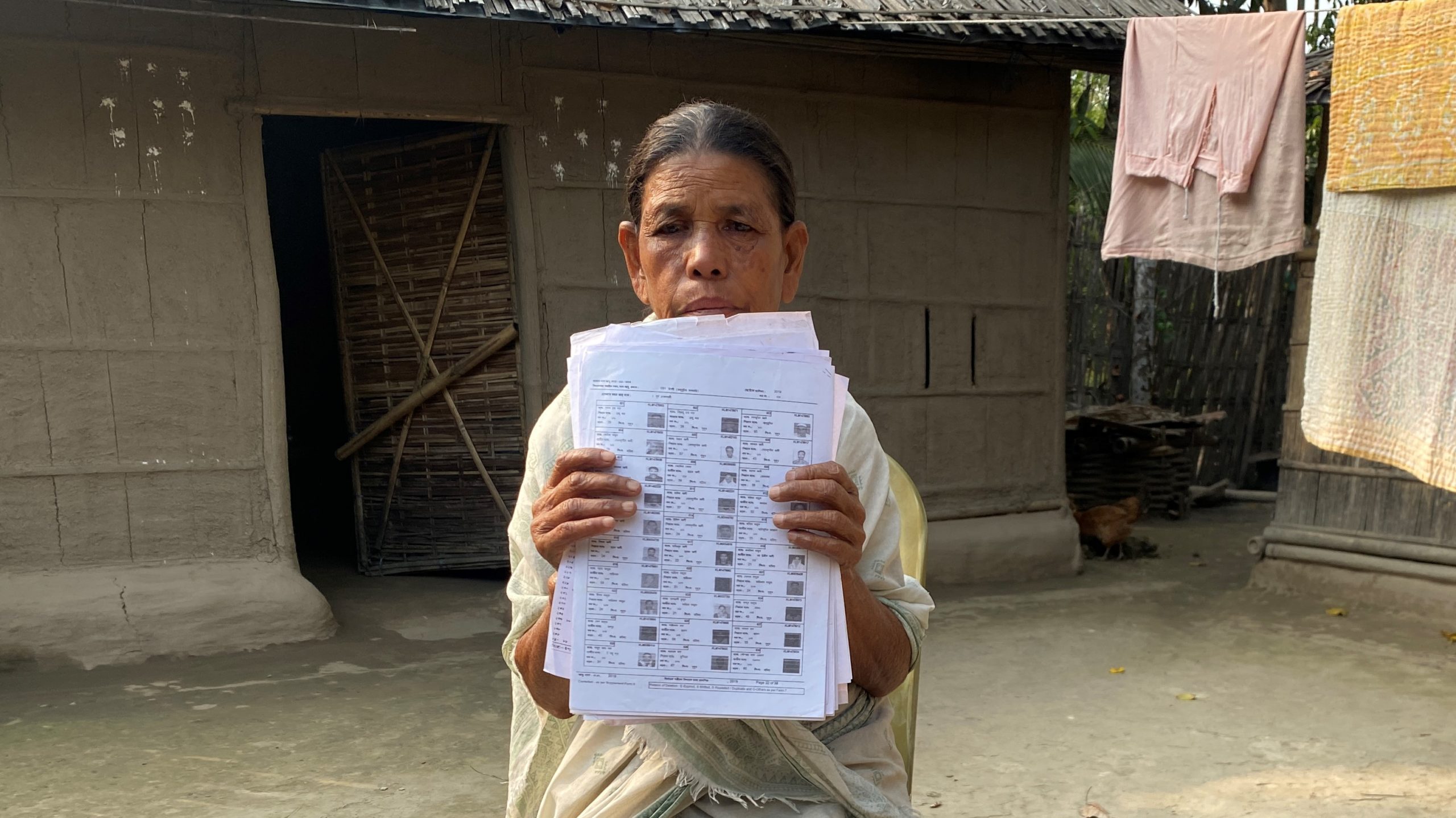

The Jeep pulled into a narrow dirt lane lined with wooden fences and straw huts on either side. We had arrived at the home of Shantibala Ray, a 61-year-old widow who spent three years, seven months and eight days in detention in district jail.

Our arrival caught the attention of Ray’s neighbors, who gathered near a fence. Ray’s daughter-in-law, shyly pulling out plastic chairs for us to sit on, welcomed us into the courtyard of her house. Ghosh hadn’t warned Ray about our visit. “She doesn’t have a phone,” he said. “But she’s always delighted to have visitors.”

Chopped wood lay on one side of the bare courtyard next to a pile of clothes hanging to dry on a long jute clothing line. On the other side, chickens pecked at scattered seed. Behind the hut, I caught a glimpse of an old woman bathing. Her body quivered as she swung mugs full of water from a bucket over her long, gray hair. It was Ray. Her daughter-in-law handed her a towel. “Come, hurry!” she said.

Ray quickly wrapped herself and scurried into the hut. When she reemerged, her hair was still dripping wet over the long, white cotton sari she had draped over her body and twisted in a thick knot at her collarbone.

She was always happy to see Ghosh: Each visit meant he might have an update about her case, which was still contested in court. She hugged him and then, seemingly flummoxed, looked at me. She took my hand into hers. “Thank you for coming,” she said.

Perhaps Ray was always thrilled for visitors to help make up for the long, lonely years she spent in detention. Not a single person had come to visit, and, in the absence of company, she said she often thought about her two cows who were at home when the border police came to take her away in February 2017. She wondered if they were fed and looked after, although she couldn’t be sure if they were even still tied to the rope in her backyard. Ray’s husband, Bhabesh Ray, had died almost a decade ago, and her only son, 21-year-old Dinesh Ray, was some 2,000 miles away, working as a daily wage laborer in the southern state of Kerala.

Ray did not think to call him when she was being taken away: “I couldn’t make sense of what was happening, of anything,” she said, her eyes welling up.

Many people in Assam say being declared a foreigner brings worse punishment than for committing a crime. In the eyes of the law, unless people can furnish a slew of documents to a convoluted legal system to prove otherwise, they are considered trespassers who need to be rounded up and put in detention. Ahead of the most recent state elections, the BJP’s manifesto stated it would undertake a process of “correction and reconciliation of entries” in the NRC, but the party was silent about implementation during the election campaign. When the BJP’s Himanta Biswa Sarma was sworn in as Assam’s current chief minister last May, he said the government would carry out a process of re-verification of the NRC. “If after that, NRC is found to be correct, the state government would accept it and take the process forward,” he said during his inauguration ceremony.

Without any clarity, those rounded up, like Ray, are left in limbo. “I still don’t understand what I did wrong,” she said.

* * *

Kokrajhar jail, where she was taken in 2017, is one of six district jails across Assam that have been converted to detain men, women and children suspected of illegally crossing into India from Bangladesh. They are incarcerated alongside those convicted of crimes including rape, assault and murder.

Such detentions are frequent: In 2019, 1,043 people across Assam were reportedly in custody as suspected illegal migrants, according to a fact-finding report by the University of California, Berkeley.

After I visited with Ghosh of Citizens for Justice and Peace, I found a 2019 Right to Information request—the Indian equivalent of a Freedom of Information Act request—that listed the total number of Assam’s detainees for 2018, the same year that Ray was inside Kokrajhar.

That year, the detention center housed 417 inmates, of which 162 were Declared Foreign Nationals (DFNs), including 13 children. Eleven were Actual Bangladeshis (ABs), including two children.

The list included the names of all detainees by surname, showing the majority belonging to the Bengali Muslim community. Ray, who belongs to the Hindu Rajbongshi community, an indigenous group descended from ancient tribes in India’s northeast, could not comprehend why she was declared a foreigner. She was born in the city of Cooch Behar in West Bengal and moved 100 miles east to the Assam village of Ekbrabari almost 40 years ago when she married her husband at the age of 16. It was here, in Assam, that she brought up her son and cremated her husband’s body after his death.

Ray may have been able to explain that to the judge presiding over her case at the foreigners’ tribunal, the quasi-judicial body tasked with deciding if a person is a foreigner or not, but she didn’t get the chance. She was never served with a subpoena to appear in court. Instead, her case was fought ex-parte, which meant that during her hearing, neither Ray nor a defense attorney was present.

Ex-parte judgments have become common for many accused, who often say they find out about the tribunal’s order only when border police come to detain them. Between 1985 and 2019, as many as 63,000 people were declared foreigners through ex-parte judgments, according to local media reports.

In an official list of all suspected foreigners held in detention, drawn up by jail administrators in response to another 2019 Freedom of Information request, Ray’s name is number 86. Under the columns that list the detainees’ passport numbers and permanent addresses in Bangladesh, her entry simply reads “Nil.”

* * *

The gates at Kokrajhar jail, where Ray was held from 2017 to 2020, are given a fresh coat of red paint every few months. So are the steel grilles behind which detainees are kept. The jail itself is built in the style of an Assam-type bungalow—an elaborate, double-story house with a thatched roof. Perfectly concealing what lies on the other side, coconut trees line a dusty entrance.

Every day, a small crowd gathers during visiting hours, from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., Monday to Saturday, and jostles to meet with inmates. Toddlers swing on the hips of young mothers, while old men bend over their canes. Most visitors haul from home heavy bags filled with fruit, soap, and oil, which they hand over to their loved ones during brief reunions.

But aside from these small rituals, the rules for visits keep changing. Earlier, visitors needed only to sign or stamp a form with their thumbprints; now, they must fill out a lengthy application stating why they have come.

Ray was glad to spare her son all that bureaucracy, but it didn’t take away from the fact that she didn’t see a single visitor in her three years inside. “I could faint, cry or become senseless. It wouldn’t matter because no one was coming to see me,” she said.

During her first few weeks, she was largely in shock and unable to comprehend what was happening. During the two mandated daily meals—a heap of rice served at lunch, along with tea and cookies served at 4 p.m.—she could barely keep any food down. It prompted the jail wardens to threaten her and force her to eat. “The other women tried to cajole me,” she said. “They used to say sweetly ‘Eat, mausi [auntie].’ I felt bad, so I would finally take a bite and hope to swallow.”

Life in detention was barely tolerable, Ray said. For women and children, the struggle took place within 16-square-meter (172-square feet) cells, smaller spaces that were carved out from a large cell area where the men were kept. The few civil society members who have been allowed to visit the detention centers have described their condition as a gross violation of human rights.

In January 2018, the National Human Rights Commission sought an independent report on Assam’s detention centers. A team of monitors, led by the human rights activist Harsh Mander, visited two jails.

Their 39-page report, published in March 2018, described “a situation of grave and extensive human distress and suffering” in the centers. Alleging that the commission had blocked all queries about the lack of official response to the report, Mander later resigned from the team.

But if there was one thing that Ray could appreciate about detention, it was that it was truly indiscriminate and secular: The jailers kept everyone inside, whether they were Bengali Muslim, Hindu or Rajbongshi. “Suddenly, we were all the same, fighting the police on one side and the government on the other,” she said.

Human rights advocates say that the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), which was passed by the Indian parliament in 2019 to allow for fast-track naturalization for non-Muslim religious minorities who arrived in India before 2014 from the three neighboring Muslim-majority countries of Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh, has emerged as a crucial tool weaponized against Muslims. Their clear exclusion has perhaps been the single largest blow to India’s secular character. Critics argue that the act is a clear violation of the Indian constitution that brings into question whether religious and ethnic diversity has a place in India’s future. And so, 73 years on from the enactment of the Indian constitution, a central question continues to vex the country: Who is an Indian citizen?

Seventy-three years after the enactment of the Indian constitution, a central question continues to vex the country: Who is an Indian citizen?

Under India’s Foreigners Act of 1946, a “foreigner” is defined quite plainly as a person “who is not a citizen of India.” But in Assam, linguistic, religious and ethnic divides have papered over the state’s acceptance of minorities, resulting in the formal declaration of foreigners.

Proving that Ray was an Indian citizen would require verification of the many, many documents she had kept all her life, familiar with the whims of an arbitrary legal system. They were neatly folded inside a plastic sleeve, stored in a small box above her cupboard, safe from the destruction of annual floods during the monsoon. The sleeve contained her husband’s land ownership documents from 1971, her father’s name on national voter lists from 1965, her voter ID and unique ID card (also known as Aadhaar), along with signed attestations from a justice of the peace and the local village chief that Ray has been a resident of Ekrabari for most of her life.

Each document traced Ray’s lineage to India, but, ultimately, doubt lingered because she was a woman. She didn’t own the land she lived on; her husband had. She didn’t vote; her father did. She didn’t have a job to show employment; her son did. Worse still, since Ray could never furnish the documents during her ex-parte court hearing, could the foreigners’ tribunal even say with certainty that she was telling the truth?

In her work Gendered Citizenship, the scholar Anupama Roy writes that “feminists of all strands” argue that “citizenship is gender blind.” Focusing on equal application of regulations, “fails to take cognizance of the fact that modern societies are steeped in patriarchal traditions.”

In the context of Assam, and India more broadly, almost all women have been relegated to the domestic sphere in a divide between public and private space, discouraging female public identity outside the home. Manorama Sharma, a professor at the North-Eastern Hill University in Meghalaya, describes a “widespread panic” among women over the requirement to submit forms to the NRC when that body first began including names in its citizens registry. At least two women committed suicide because they could not find the necessary documents to prove their lineage.

The exclusion of women from the citizenship debate also extends to their ability to defend their citizenship. At hearings, the police and court officials often address the men who accompany women. If Ray, who is a widow, had been informed of her hearing, she would have had to leave the house to travel hundreds of miles alone to her court hearing. But she never left her backyard, let alone her village or district, by herself.

The situation is often even more difficult for those outside the institutions of marriage and family: single women, orphans and non-binary gendered people. Members of the transgender community were completely left off the NRC list. So far, the state government hasn’t directly acknowledged any problems addressing gender in the process, but has announced free legal aid to all applicants left off the final list.

Ray languished in detention for three years before India’s laws on detention and bail began to change. In May 2019, the Supreme Court ruled that inmates who have spent more than three years in detention could be set free on conditional bail as long as they provide biometrics, proof of address and a bond of 100,000 rupees ($1,320). In some cases, detainees are asked to register weekly at their local police stations—but that can mean making long commutes often by foot, even by the ailing elderly.

The following April, in the wake of the COVID-19 outbreak, the urgency to decongest prisons and detention centers led the courts to lower the time-in-detention requirement for bail candidates to two years and reduce the bond amount to 5,000 rupees ($65).

That’s when a team of caseworkers from CJP, which is based in Mumbai, began to work on ensuring the bails of detainees like Ray. They first approached her on a field visit to the Kokrajhar detention center sometime in late 2020. CJP representative Nanda Ghosh noticed that Ray had completed the requisite time for detention and had all the documents needed to qualify for bail.

Ghosh approached Ray’s son, Dinesh Ray, about posting bail for his mother. To do that, he had to prove he is a citizen of India, too: His name had to appear in the NRC; he had to establish his lineage to his father to show ownership over his father’s property deeds. He also had to show he was paying land tax, produce his voter ID and voters’ lists with his name on them and provide his birth certificate and Aadhar card as proof of identification.

In the bail applications with which CJP has assisted, a third of the cases contained no proof of permanent land ownership because the applicants were homeless, Ghosh said. And finding a bailor becomes an impossible task when most detainees’ family members and neighbors are poor or rootless, he added.

“Even when CJP was able to find people who met all the criteria and had the necessary documents, they would be unwilling to help because they didn’t want to face harassment or [a] social boycott for helping someone perceived to be a ‘foreigner,’” Ghosh explained.

* * *

It was their next-door neighbor who broke the news of Ray’s arrest to her son over the telephone all those years ago. She urged him not to return home from Kerala, where he was working at the time, because often children of “doubtful” citizens or foreigners end up becoming entangled themselves in the web of doubts over citizenship.

The only time he visited his mother was in 2019, after Ghosh and CJP told him that, given her case history, Shantibala Ray stood a real chance of bail. That day, Ray put on a clean shirt and combed his hair, while his wife donned a pink sari and put red vermillion on her hair part to indicate her newlywed status.

A year after his mother’s detention, Ray had moved back to Ekrabari to look after their home. He married a local girl from their village, but, with neither of his parents around, the wedding was a plain affair with no celebrations.

In Kerala, where Ray was lifting bricks as a manual laborer for eight hours a day, he said he had often pictured his elderly mother trembling in a corner of the jail cell, waiting for his return.

On the day of their visit, his wife told me she packed some cookies, fruit and nuts in a small bag for his mother, while he collected the couple’s documents in case they were called in for questioning at the detention center. He was nervous to see his mother again, ridden with the guilt and helplessness of the previous three years when he had all-but given up hope of seeing her again.

Alongside Ghosh, the couple entered the Kokrajhar detention center with a sense of trepidation—could the police arrest Dinesh Ray, too? In the waiting room, Ray’s wife described observing the chaos of other visits with a nervous stillness. As long as they didn’t move or say anything, they could steer clear of attracting any attention, she believed. An hour later, Shantibala emerged from her cell. Her eyes were filled with tears as her trembling hand reached for her son’s. In that moment, he said, he wanted to curl up into a ball and rest in his mother’s lap. Instead, he remained tightlipped and just smiled. He dragged his wife forward between them, who handed her the bag of fruits and nuts and said, “This is your new daughter-in-law.”

I asked Shantibala Ray to recall April 22, 2020, the day she was released. She told me she woke up that morning, drank a cup of tea and braced herself for what would happen next. “I’d spent so long trying to accept that the cell was my home now, I was scared that [my release] would turn out to be a lie,” she said. But that afternoon, she was handed back her cotton sari, now musty and faded, so she could change out of her jail uniform.

There were many tears as well as envy among her fellow detainees as she hugged them goodbye. All conceded Ray’s case had been particularly tragic, she said. Even now, her son wasn’t there to collect her at the gates because he had to work.

Even after two years on bail, Ray seemed confused. Darkness descended on her wrinkled face whenever I asked questions about her time in detention. Many times, she burst into tears. “Nothing is the same as before,” she told me. She has aged, developed hearing problems and found readjustment to ordinary life difficult, especially around friends, relatives and neighbors who keep their distance to avoid becoming state suspects themselves.

The tag of being a foreigner seems inescapable, sometimes even in her backyard. Neighbors sold her two cows when she was taken away to detention, and they’ve since been replaced with chickens. Most afternoons, Ray sits and sunbathes in the courtyard while her daughter-in-law dries firewood to sell in the market. She and her son barely speak to each other when he returns home from work. They opt to eat their dinner in silence before retreating to bed.

Ghosh, who witnessed the emotionally ridden reunion between mother and son, recognizes the sadness in these interactions. “It’s as if the joy of human freedom has been crushed by the denial of dignity,” he said.

Ray says she thinks about her case endlessly, wondering when Assam’s High Court might finally decide that she is Indian, not a foreigner: “I’m so old now, all I want is to die in peace, knowing that I died an Indian,” she said. “Because I still don’t know where Bangladesh is.”

Top photo: Shantibala with her daughter-in-law in the yard of her hut in the village of Ekrabari