TROMSØ, Norway — “We are living in a reversed 1989 era,” said the State Secretary to the Norwegian Minister of Foreign Affairs Maria Varteressian, standing on a stage in the Clarion Hotel in late January. “All of the trends and arrows that were pointing in the right direction—democracy, trust and optimism—are going down.”

It was day two of “Arctic Frontiers”: the annual international gathering of researchers, politicians, Indigenous representatives and business leaders to discuss “economic, social and environmental sustainable growth in the North.” This year, more than 1,300 people arrived from more than 35 countries for four days of panels, debates and presentations at this stately fjordside hotel.

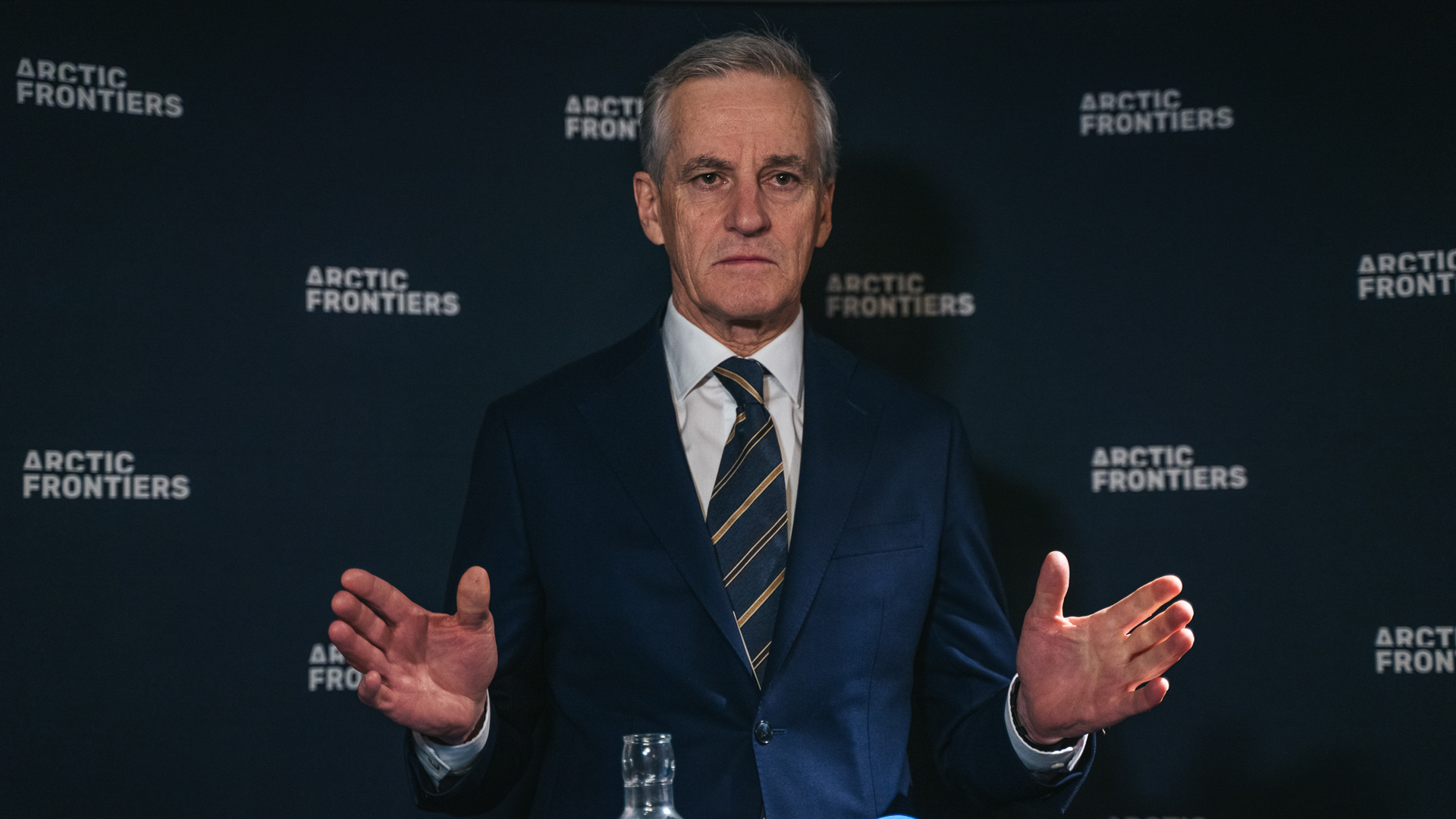

Since its inception in 2007, Frontiers has been billed as a science conference. But this year’s event, beginning with a welcome from Norwegian Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre, felt palpably political. In the Arctic, it’s often impossible to separate the two: After the Cold War, new border-crossing scientific partnerships helped power an era of polar peace.

But since Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, as Varteressian noted, that era has been coming to a close. Shortly after the invasion, Western countries sanctioned science collaborations with Russian partners, cutting off data from half of the geographical Arctic. Three years later, most circumpolar collaborations remain on ice, and military and economic tensions are rising. Last year, Finland and Sweden joined NATO, and Russia has steadily been strengthening ties with China.

I’m not a frequent conference-goer. But the week’s events—ranging from high-level defense debates to marine biologists presenting whale migration data—felt like a curiously motley arrangement of diverse, and often conflicting, agendas. The hotel’s enclosed lobby heightened the effect: Standing under blue and white conference banners, officials snacked on cookies with industry executives, Indigenous leaders, graduate students and activists. In the best cases, you could call it a rare space for cross-disciplinary connection. In other moments, it was a stage for a collision of interests.

As it turns out, I was observing what may be an Arctic-specific phenomenon. In 2021, the Arctic Review of Law and Politics published a paper by University of Tromsø political scientist Beate Steinveg on the “Arctic Conference Sphere,” focusing on Frontiers and the other major annual high North conference, the Arctic Circle Assembly held in Reykjavik every October.

In the Arctic, she argued, “the necessity for hybrid policy-science-business conferences arose from a more complex governance system and challenges requiring cross-sectoral, interdisciplinary, and international collaboration.”

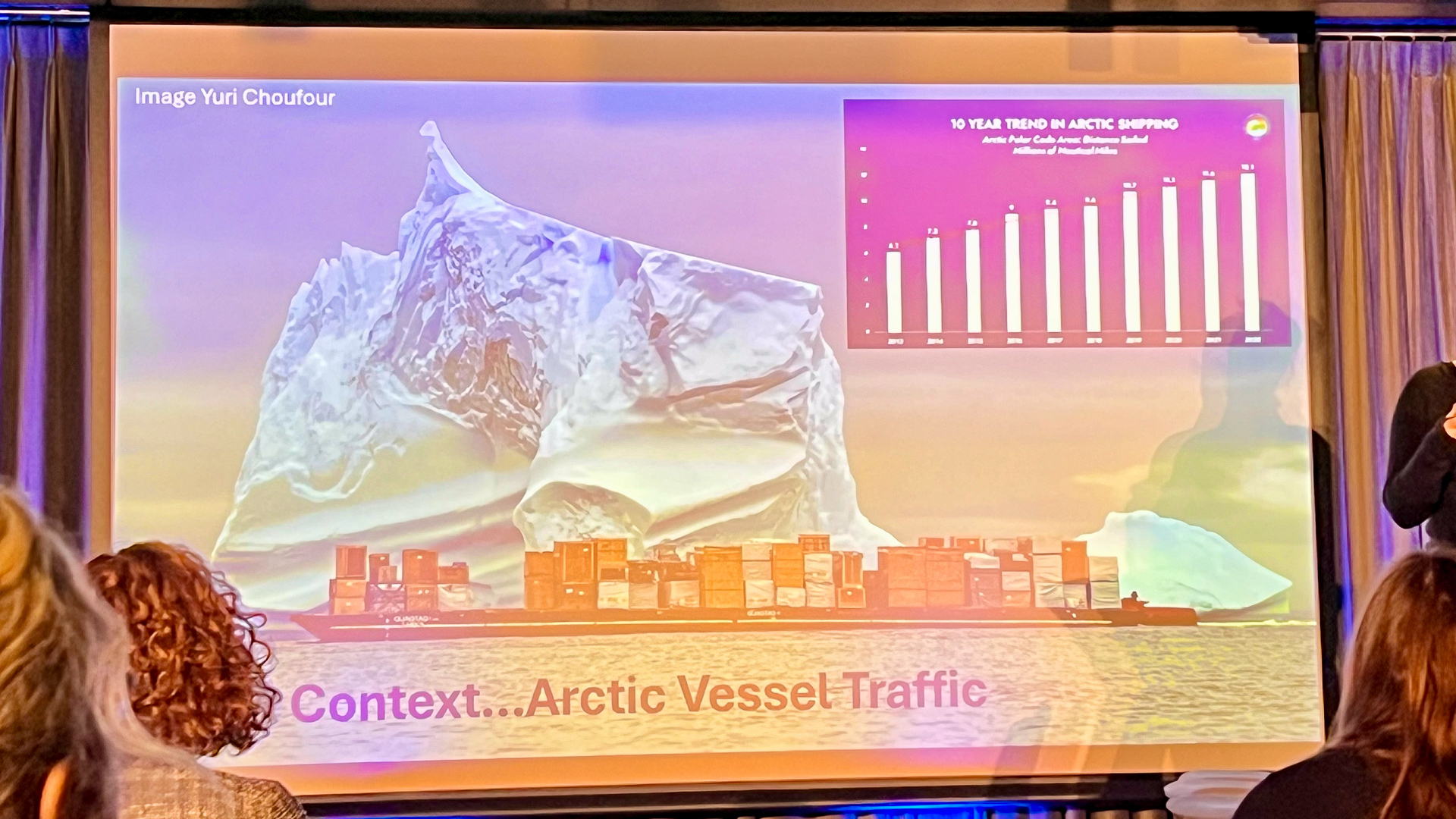

In other words, the Arctic is an undeniably distinct region. But it’s also crisscrossed with a messy patchwork of national and international law, governments and sovereign peoples, and cross-border scientific projects. To pull them all together, these week-long conferences carry an outsized significance in Arctic affairs. In the past decade or so, as Arctic ice melt has exposed new sea routes and resources, the forums have been growing in size and influence—adding attendees from non-Arctic states such as the United Kingdom, Germany, France, China, India and more. (Russian representatives have not attended since 2022.)

This year, Russia wasn’t the only Arctic state causing controversy. The event took place just one week after the United States presidential inauguration, and less than a month after President Donald Trump demanded the annexation of both Greenland and Canada. In the weeks leading to the event, former President Joe Biden-appointed US representatives disappeared from the conference program. Other American representatives, like Senator Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, had to join by video from Washington, DC, where she was assisting with the White House transition. Among officials from other Arctic states, the attitude toward the newly aggressive US leadership felt both fearful and humorous.

“One week down, 207 to go,” quipped Norwegian Foreign Minister Espen Barthe Eide when asked about the new US administration.

The week was peppered with such notable moments. But this dispatch will not attempt to summarize an entire conference—not least because concurrently running events made it impossible to attend it all. Still, in the great wash of ideas from scientific experts and state leaders, certain themes repeatedly rose to the surface: words like “progress,” “threat” and “security.” And, hearing this shared vocabulary expressed in such varied contexts, I began to wonder what exactly each speaker meant.

“The Arctic” is the most obvious example. It’s not just a vast region; it’s an imagined idea, encountered, studied and governed from extremely varied perspectives. We can agree on the latitudinal definition: the territory above 66°33’ N. But from there, I wondered, what did each of these speakers picture? A collection of societies, including the world’s highest concentration of Indigenous peoples? A fast-warming lever of global climate? A vast marine ecosystem, only fringed by land? A thin-stratosphere entryway to space? A resource-rich zone of economic opportunity? A military theater? A home?

The year’s conference theme, “Beyond Borders,” captured this multiplicity of meanings at work. That theme was likely chosen to emphasize the importance of circum-polar cooperation. Yet, taken another way, it also highlighted the fact that Russia, the largest Arctic state, clearly has no respect for Ukraine’s borders. At best, a border is a shared idea, to be mutually set and mutually observed. But the week’s discussions revealed extremely divergent understandings of where different physical, legal and ethical “borders” lie—and how to best secure them.

* * *

“It is a different Arctic than we once thought. We are in darker times,” Norwegian Foreign Minister Eide said during a panel discussion. “[I]n order to go ‘beyond borders’—the title for this year’s conference—it is important to have clear borders as a foundation.”

Eide was responding to a recent threat to an Arctic border: President Donald Trump’s bid to purchase Greenland. His proposal came up frequently during the conference as a signifier of both heightening Arctic economic tensions as well as the waning star of American leadership in the Western alliance. In the same conversation, US Senator Lisa Murkowski affirmed the sovereignty of the Greenlandic peoples, warning about the “colonial mindset” that Trump’s stated interest in the country’s resources implied.

“When you hear about the Arctic, there’s very little mention of the 56,000 people in Greenland,” she said. “That does not mean they should be ignored or shoved aside.”

But Eide’s statement also revealed an apparent blind spot of his own. His state-centered emphasis on secure national borders, particularly in the Arctic, omitted the reality of many of its Indigenous peoples whose cultures predate and transcend the boundaries of nation-states. For peoples such as the Sami, whose population spans Sweden, Norway, Finland and Russia, recent closures of the Russian border have fractured communities and caused disproportionate harm.

Indeed, in a few notable cases during the conference, Arctic Indigenous sovereignty—a legal if not geographical “border” upheld by the 1989 United Nations Convention on Indigenous rights—seemed sidelined. It typically occurred in conversations about securing the interests of nation-states.

One session, “China’s Role in Supply Chains of Critical Minerals and Materials: Consequences for Nordic Countries,” exemplified the tension. Europe’s race to develop clean energy has exposed economic vulnerabilities: Most of its rare earth minerals, needed to power electric vehicles and grids, currently come from China. The energy crisis sparked by 2022 fossil fuels sanctions against Russia provided a brutal wake-up call about the need to work toward energy independence.

Luckily for Europe, Arctic melt has recently exposed new mineral supplies. On the panel, Carina Sammeli, the mayor of Luleå, Sweden, spoke about her northern city’s role in this global dynamic: alongside opening a new graphite anode mine—to extract a mineral crucial to lithium battery production—they’re set to build Europe’s first major battery plant. Sammeli described the development as hard on the city’s 78,000 residents, not least because entire homes would have to be moved to another section of the city. But, she said, residents would benefit from new jobs and with time learn to adapt.

Seated next to Sammeli, Eirik Larsen, head of the Human Rights Unit of the Sami Council, said this story was one of many examples of Indigenous peoples unjustly equated with “not-in-my-backyard” residents. He pointed to a wrinkle in the narrative of regrettable-yet-necessary development: Indigenous peoples are not the same as “locals,” and possess rights that precede and transcend both local and state agendas.

“From my perspective, it’s quite hard to hear someone speak so enthusiastically about mining extraction on Sami land,” he said. “This is not our backyards. It’s our front yard, our living room.”

Nordic green development had too often failed to adhere to states’ duty to obtain Indigenous peoples’ “free, prior and informed consent,” Larsen said. In the most notable case in 2021, the Norwegian Supreme Court ruled that the government had violated international human rights law by approving that Fosen Wind, Europe’s largest windmill farm, be built on reindeer-herding territory. In the context of European energy development, officials often talk about “security” from global dependencies, particularly adversaries like Russia and China. But in practice, Larsen said, that often directly ignores the security of Indigenous peoples.

“The greatest threat to Sami security is land encroachment.” he said. “We shouldn’t be in a situation where China’s minerals are a kind of security for the Sami culture.”

The following day’s main panel, “Beyond Traditional Security,” assembled state, NATO and EU military leaders to discuss new threats challenging conventional approaches to defense. As a climate journalist, I came with my own lens: I had expected that participants would at least mention some of the risks posed by climate change. Instead, the discussion focused on the recent rise of hybrid threats such as cyberattacks and sabotage to undersea cable infrastructure. (A concern I covered in my last dispatch.)

Speaking on my own panel later that afternoon, I was resolved to voice what I’ve heard from scientists time and again: that the greatest security threat facing humanity is climate change. As it turns out, that perspective caused some friction.

The “Arctic Security Seminar,” chaired and moderated by Fridtjof Nansen Institute senior researcher Andreas Østhagen, started with a discussion between Canadian Senator Pat Duncan, Norwegian Brigadier Steiner Kongshavn and Indian Rear Admiral TVN Prasanna about the shifting security landscape. Østhagen asked me to be one of four “analysts”—two academics and two journalists—to follow.

Just before the panel, I spoke with Brigadier Kongshavn. He told me that he hears the same feedback from both scientists and security think-tanks: that climate change is the greatest threat for militaries and society alike. That is particularly true in the fast-warming Arctic, where rising temperatures and extreme weather are already transforming combat environments, and threatening food, water and power supplies.

So when Østhagen asked me about how journalists think about covering Arctic security, my answer had climate top of mind. Not just the direct consequences of climate change but also the risks posed by growing inaccuracies in climate models since Western sanctions cut off data from the Russian Arctic. In order to prepare for, and mitigate, climate change’s worst consequences, I said, we need to be able to accurately predict what will happen and when. The breakdown in shared Arctic data has compromised that effort.

“In my view, it is a security threat that Western sanctions have halted crucial climate collaborations in the high North,” I said. “The greatest risk facing the planet is climate change.”

Østhagen pushed back: “I’m more worried about Russian potential escalation and maybe even invasion, if things go really bad than I am about climate change,” he said.

I understood his point—and I hadn’t intended to set conflict and climate change against each other. In fact, I don’t believe you can separate the two. In the modern era of geopolitical analysis—to paraphrase a concept I learned from a University of Tromsø politics professor named Rasmus Bertelsen—we have to acknowledge that the “geo-” is shifting and influencing the “-politic” like never before.

Climate change is the future’s great border-violating force. As rising waters and melting ice redraw the lines between nation states, storms and fires invade our communities, and droughts and biodiversity collapse wreak havoc on the global food supply, it affects our adversaries just as much as it affects us. That is particularly true of Russia. Its most-militarized zone, housing the Northern Fleet, centers around the Arctic Kola Peninsula. All its nuclear-powered submarines are in the fast-melting North. And it’s deepening an alliance with China based on the promise of the Northern Sea Route, which, for the first time in history, will likely soon allow shorter-than-ever sea crossings from Asia and Europe.

Unlike a state or terrorist threat, climate change is a faceless, unmotivated enemy. It defies traditional defense playbooks because we can’t negotiate with, threaten or deter it. Yet it’s still capable of colossal damage. Indeed, security experts have recently coined a new term to encapsulate that challenge, “actor-less threat.” Climate change is demanding entirely new planning and response strategies—and some of the world’s biggest military apparatuses are responding in kind. In 2023, NATO opened the Center for Excellence on Climate Change and Security in Montreal, Canada. Since 2021, the United States, Germany and Australia have all incorporated climate change into their national security strategies.

(Until the recent administration change, the US was the global leader in the field of climate security. But in mid-March, the new administration announced it was cutting all climate research at the Department of Defense. “[DOD] does not do climate change crap,” Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth wrote on X in March. “We do training and war fighting.”)

The “securitization” of climate change comes with its own complications. As I acknowledged during my panel discussion, there is inherent hypocrisy in even the US military’s most climate-forward agenda: The world’s militaries contribute 5.5 percent of global fossil fuels emissions, more than twice those from the airline industry. And America contributes two-thirds of that. Still, the mobilization of global militaries acknowledges that climate risks aren’t the sphere of future-modeling scientists; they’re a present and ever-growing reality.

Norway’s leader, as it turns out, takes the threat quite seriously. Directly after my panel, a Norwegian climate scientist and co-author of the 2021 IPCC report approached me to thank me for my comments. And he told me that just a few hours earlier at this very conference, Prime Minister Støre had said in an interview that climate change posed a greater national security threat than nuclear escalation.

With the 2014 Paris Climate Agreement, the world’s nations set a collective “border”: to reduce fossil fuels emissions in order to keep the rise of global temperatures within 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2030. In 2024, not only did global temperatures pass that limit but emissions also hit the highest levels in recorded history.

So global climate conversations are increasingly turning to other solutions. And the conference’s final, and most controversial, debate centered around what was long considered an uncrossable ethical threshold: to drastically interfere with global climate through geoengineering technologies.

The scientific community has largely rejected geoengineering research for decades, both because it distracts focus from reducing emissions and because any techno-fix inevitably comes with unknown risks. In recent years, however, as our shared climate future has looked increasingly grim, potential climate-cooling technologies have gained traction.

On the smaller scale, that might look like “cloud seeding” to induce local precipitation or artificially refreezing Arctic sea ice. The largest-scale planet-cooling solutions start to sound like sci-fi, from space mirrors that would reflect the sun to “stratospheric aerosol injections” (SAIs) that would maintain a constant global cloud cover. The Arctic, where the globe’s fastest changes are taking place and the stratosphere is thinnest, would be the base for launching many such technologies. Interest in SAIs in particular has been growing in recent years.

The following day’s debate assembled several scientists, an entrepreneur, an ethicist, a legal expert and a Sami leader. Helene Muri, director of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, expressed a dilemma facing scientists: They well understand that the world is “running out of time” to reduce the likelihood of the most catastrophic outcomes from the current trends of carbon emissions. With the clock running out on emissions reductions, the risk calculus over technologies they have long opposed is quickly changing.“As a climate scientist, I have a quite heartbreaking job,” she said. “And it is pure but very real desperation that some are investigating these solutions.”

Providing an example, University of Exeter Professor of Political Theory Catriona McKinnion noted that geoengineering raises serious governance and ethical challenges. The largest-scale interventions would require a new international agreement and a potential UN body to sustain it over decades or more. But, even if we were to reach global consensus around them, some technologies raise questions about justice: They would inevitably be developed in the global North and deployed with unknown consequences for the global South.

Gunn-Britt Retter, head of the Arctic and Environmental Unit of the Sami Council, made a similar case. “Playing God” to alter nature, she said, directly contradicts Indigenous ideas about human relationships to the natural world. Further, she cautioned against the hubris involved in attempting to invent our way out of a problem rather than the harder work of producing and consuming uncomfortably less than we do now.

Leslie Field, CEO and founder of Bright Ice Initiative, a Himalayan glacier-restoration project currently in development, said the broad term “geoengineering” unnecessarily lumps smaller-scale projects like her own with massive projects like SAIs. But she added that testable small-scale climate interventions, paired with mitigation strategies like carbon sequestration, can help prevent turning to those last-resort, more dramatic measures.

“We are starting small and will test, test, test,” she said. “It’s not going to be some sudden global shock.”

Stratospheric aerosol injections are appealing for their near-immediate effect; models show they would noticeably cool the planet within a year and enable reaching pre-industrial temperatures within 30 years. But they would also likely alter global ecosystems in ways we still don’t understand. That is a border that, once crossed, would remain closed. But that’s true of every step into the future of climate change. And as we stare into the undeniable future coming for the rest of the planet, those in the Arctic have front-row seats.

In some ways, ending the conference on this balanced debate highlighted the best of what can come from an event like Arctic Frontiers. After all, before the West embarked on its great industrial experiment, 19th-century captains of industry likely didn’t convene to weigh the potential unintended consequences. And they certainly wouldn’t have included ethicists or Indigenous leaders at the table.

Notably, however, none of the panel’s speakers held decision-making power. Even the politicians present won’t be held accountable for their words, nor will they be asked to produce measurable outcomes. In the worst case, such a conference offers leaders an opportunity to pay lip service to issues like Indigenous sovereignty and climate protections without following through with hard policy.

As Eirik Larsen of the Saami Council noted, when it comes to high North land use decisions, “consultation is not the same as consent.” In any case, conferences are hardly a form of co-governance. Conversation can inform but can’t replace action.

What, then, does the so-called Arctic Conference Sphere accomplish? There’s plenty to criticize about Frontiers: It’s expensive to attend (a whopping $240 per day for standard tickets), and, as one researcher told me, often quite abstracted from local concerns—many in the bustling city center outside the Clarion Hotel had no idea it was taking place.

On the other hand, we can’t underestimate the power of simply coming together. Since Western sanctions ended science partnerships with Russia, researchers have told me, we haven’t just lost datasets. We’ve lost other forms of common understanding that scientific co-creation, and events like conferences, help maintain. The good faith “intangibles” built by sharing space, sipping coffee or snacking on cookies are a form of diplomacy in themselves. They emerged from a rare historical moment, the “1989 era” of democracy, trust and optimism that the Foreign Ministry’s Varteressian warned is reaching its twilight.

Russia’s three-year absence from these Arctic forums, and even the last-minute rearrangement of many Americans’ presence this year, highlighted the effect. Conferences may offer platforms for platitudes, posturing and plenty of people talking past each other. Yet, left in isolation, we would lose the chance that our disparate, manifold pictures of the world, or of the Arctic, might be complicated, challenged, or even converge—if only for an afternoon in a hotel event hall.

Top photo: Swedish dancer Eva Soneblum leads audience members in dance during a panel titled “Culture as Emergency Preparedness” at the Arctic Frontiers conference (David Jensen, Arctic Frontiers)