CESME, Turkey — For visitors from the Greek island of Chios, this bustling resort town, only a 30-minute ferry ride across the Chios strait, feels almost like home. Cesme was known as Krini in Greek, both names meaning “spring” or “fountain” because of the region’s abundant water sources. The imposing Genoese-built fortress defending the harbor reminds one of Chios castle, which the Genoese also expanded. Walking along cobblestone streets with black and white pebble designs, I smell the piney aroma of mastic saplings. The authorities have been planting them in burned forest areas in a bid to challenge Chios’s monopoly on the rare mastic resin.

Turning onto Atatürk Boulevard, I try the locked doors of Agios Charalampos, formerly Cesme’s central Greek Orthodox cathedral and now a cultural venue. A few shops down, I stop at Rumeli Patisserie to enjoy desserts similar and yet different from those on the island: chewy mastic ice cream, fig and lemon blossom jam, and caramelized kazan dibi made by the descendants of Thessaloniki-born Muslims who immigrated to Cesme during the 1923 population exchange.

But for the Anatolian Greeks of Varvasi, a neighborhood on the outskirts of Chios town, the ties go deeper. Cesme was the homeland their ancestors lost during the Asia Minor Catastrophe of 1922, when a crushing Greek military defeat led to the destruction of cosmopolitan Smyrna (now the Turkish port city of Izmir) and the forced exodus of Greeks from Asia Minor. Despoina Balkiza, Greece’s consul general in Izmir, 90 kilometers away, described the catastrophe as “perhaps the most important chapter in the modern history of the Greek state.” In a written interview, she told me that “memories of the Greek presence here for centuries until 1922 and its violent expulsion are kept alive not only by the descendants of the refugees, but by all Greeks.”

Indeed, the loss of Anatolia, the end of Greek expansionism and influx of some 1.3 million Orthodox Christians—over a quarter of Greece’s population at the time—profoundly changed the face of the nation. Then, as during the 2015-2016 migrant crisis, islands off the Asia Minor coast like Chios were first reception centers for refugees. The communities that settled on Chios contributed to the island’s cultural and economic life. Many worked in Greek shipping.

The 1922 events came a century after another cataclysm, the 1822 Chios massacre, in which over 80 percent of the Christian population was slaughtered or enslaved by Ottoman troops. Both dates remain fraught for Greeks. As the island commemorated the centennial anniversaries last summer, Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan warned Greece not to forget Izmir and threatened to “come suddenly one night.” But of the two, Chian filmmaker Eirini Steirou believes 1922 is “more present in collective memory” and “more connected with the reason Turkey is seen as wanting to do real harm to the Greeks.”

To explore how the Asia Minor Catastrophe impacted Greek society and local perceptions toward Turkey, I visited the Anatolian coast and refugee neighborhoods on Chios and Oinousses. Although few traces of the Greek presence in Izmir remain, the Anatolian Greeks I met are actively engaged in island life, committed to keeping their history and traditions alive.

The end of the Greek presence in Asia Minor

Western Anatolia, including the Izmir Peninsula, was home to Greek communities since antiquity. After the revolution of 1821, when Greece liberated itself from the Ottoman Empire with the help of the European great powers, the new state harbored ambitions of expanding its territory to encompass the Greek populations still under Ottoman rule in the southern Balkans, Anatolia and Aegean islands. The Megáli Idéa or “Great Idea” gained momentum as the Ottomans suffered defeats in the Balkan Wars and World War I.

After the war, the Allied powers gave Athens a foothold in Anatolia, authorizing the Greek army to occupy Smyrna and the surrounding region to protect the Christian population there. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Smyrna was the “eye of Asia,” a vibrant cultural and commercial crossroads between East and West. The historian Lou Ureneck described it as the “richest and most cosmopolitan” city in the eastern Mediterranean, home to half a million Greeks, Turks, Armenians, Jews and Levantines. It was known for its tobacco, carpets and figs, as well as its marble mansions, garden parties, gambling parlors and opium dens.

All that ended in the final act of the Greco-Turkish War, when Turkish forces led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk broke through Greek defenses and chased the retreating army westward to the Mediterranean Sea, recapturing all the territory Greece had occupied since May 1919. The Greek army abandoned Smyrna, leaving the city’s Christian inhabitants to fend for themselves. Turkish troops marched in on September 9, 1922, a day still celebrated as Izmir Independence Day.

Chrysovalantis Stamelos, a Greek-American filmmaker who has lived in Izmir since 2010, explained the Turkish perspective. “They’re celebrating the end of a very long war,” he said. “They were strong enough and united enough to fight an invading army. Greeks see it as the loss of the motherland, whereas Turks see it as the solidification and rebirth of the fatherland.”

Stamelos, whose great-grandparents fled from Krini to Chios during the catastrophe, returned to Izmir to rediscover his roots. When I visited the city last August with volunteers from the Greek America Foundation, he gave us a tour of the 3-kilometer waterfront, where multi-story apartment complexes and palm tree-lined avenues stood in place of the neoclassical mansions I’d seen in sepia-toned photos. The renovated quay seemed too new for ghosts, but 100 years ago, this was where the painful final days of the city’s Christian population played out.

With the arrival of the Turks, violence and terror descended on Smyrna. Soldiers and irregulars looted, raped and murdered Christians in their homes. Corpses lay on the streets and floated in the harbor while Allied warships waited in the bay, ordered to evacuate only their own citizens. On September 13, fires broke out in the Armenian neighborhood, leaping from building to building and uniting in a blaze that consumed the Greek and European districts, erasing all traces of what the Turks called “infidel Izmir.” Residents flushed from hiding by the fire joined panicked refugees amassed along the waterfront, all desperate to escape. George Horton, the American consul in Smyrna at the time, estimated the deaths at over 100,000.

Who was responsible for the burning of Smyrna is still debated. Greek Consul General Balkiza said the destruction was “based on an organized plan” to rid the city of its Christian inhabitants, and Western eyewitnesses describe Turkish soldiers setting buildings aflame. On the other hand, Stamelos said, most Turks link the fire to the Greek army’s scorched earth policy as it retreated from Central Anatolia and see a parallel with the great fire of Thessaloniki in 1917. Now a high school film instructor, he told me that many young people “don’t really know” or care about what happened back then.

Thus ended the Megáli Idéa and over 3,000 years of Hellenism in Asia Minor. Help for the displaced finally came on September 24, when the American humanitarian Asa Jennings organized the evacuation of women, children and the elderly to Greece on merchant ships from Lesvos, Chios and nearby islands. Some 125,000 men were not permitted to depart, however. They were sent to labor battalions in the interior, and very few survived. After Smyrna’s quay had been emptied, evacuations continued for months all along the Anatolian coast.

The expulsions were formalized when Greece and Turkey signed the 1923 Lausanne Convention, agreeing to a compulsory exchange of their Christian and Muslim populations, exempting Greeks in Constantinople and the islands of Imbros and Tenedos, as well as Muslims in western Thrace. Beaton notes that the convention set a “baleful” precedent for the transfer of peoples against their will as a 20th-century solution to population problems. In the documentary Smyrna: The Destruction of a Cosmopolitan City, historian Alexander Kitroeff observes that the catastrophe also signaled the end of the eastern Mediterranean’s multi-ethnic cities, all of which “eventually disappeared and gave way to national cities.”

Beneath its veneer of conspicuous newness, little remains of the city Izmir once was. The leveled Armenian quarter was turned into the Izmir Culture Park, a 420,000 square meter green space hosting fairs and exhibitions. Agios Vukolos, a Greek Orthodox church built in 1886 near the central train station survived, as did several Greek mansions on the north end of the quay. In Cumhuriyet Square, the municipality erected an imposing bronze statue of Atatürk on horseback, urging his troops onward to the Mediterranean.

The two pillars of Varvasi

The displacement of Anatolian Greeks was one of the first major humanitarian crises of the 20th century. By December 1922, over 868,000 refugees had arrived in Greece. Fleeing from their homes, they brought few possessions and were in a wretched state.

On Chios, the municipal garden, Vounaki square and the port became gathering places for the dispossessed. They took shelter wherever they could: in public buildings, schools, warehouses. They faced water shortages, sanitation problems and outbreaks of typhus and dysentery, as well as discrimination from locals. Although they were Orthodox Greeks, they were called tourkósporoi, “Turk-spawn,” and prόsfinges, a derogatory form of “refugees.”

Kaiti Chouli, whose great-grandmother fled from Krini to Chios as a 23-year-old widow with a two-year-old child, explained the locals’ antipathy. “In the beginning, they thought the refugees would be a burden on the local population,” she said. “Very quickly, however, they learned that the refugees were sophisticated. They were cheap laborers who knew how to work the earth, they had expertise and artistic skills, and they helped Greece advance after the war.”

Organizations like the American Red Cross, Near East Relief Committee and British Save the Children Fund provided much-needed aid. Eventually, refugees integrated into existing villages, and within three years, the government established settlements for them in the moat of Chios castle, in Fragomahalas, where I lived when I moved to town, in Agia Paraskevi on the coastal road after the hospital and in Varvasi on the southern outskirts of Chios town.

Varvasi is a roughly rectangular district with streets named after the villages people had left behind: Krini, Kato Panagia, Alatsata, Vourla, Lithri. When the first residents moved in, the streets were still dirt roads and entire families, five or even 10 people, lived in small houses with just two rooms and a kitchen. Now most of the original houses are abandoned, or they’ve been torn down to build modern one- and two-story homes. Two institutions serve as pillars of the community: Agios Charalampos, the cathedral in the heart of Varvasi, and the Cultural Association of Varvasi “The Lighthouse” Library, a community space founded in 1957.

I soon learned how friendly the residents were. One morning, when I dropped by to take photos of the church, an elderly man named Antonis fetched the priest from his home to meet me. Páter Nektarios showed me around: “If you took a photo of this neighborhood from above, it would seem like we’re a holy monastery with a central church, and around it, instead of cells, are the homes of the people here,” he said. I agreed—the social network seemed very tightly woven.

Made from the island’s distinctive, rust-colored limestone, the three-aisled, ceramic-roofed basilica was named after the metropolitan church in Cesme. Originally built in 1927, the church was damaged by an earthquake in 1949 and rebuilt from scratch in 1967. Greek flag pennants hang from the belltower. The arches above the front door and windows are decorated with gold mosaics representing the saint and two angels. In the church’s courtyard stands a marble column engraved with the names of the lost homelands, and beside the church is a peaceful, well-tended garden. I could tell how much care and pride went into maintaining it.

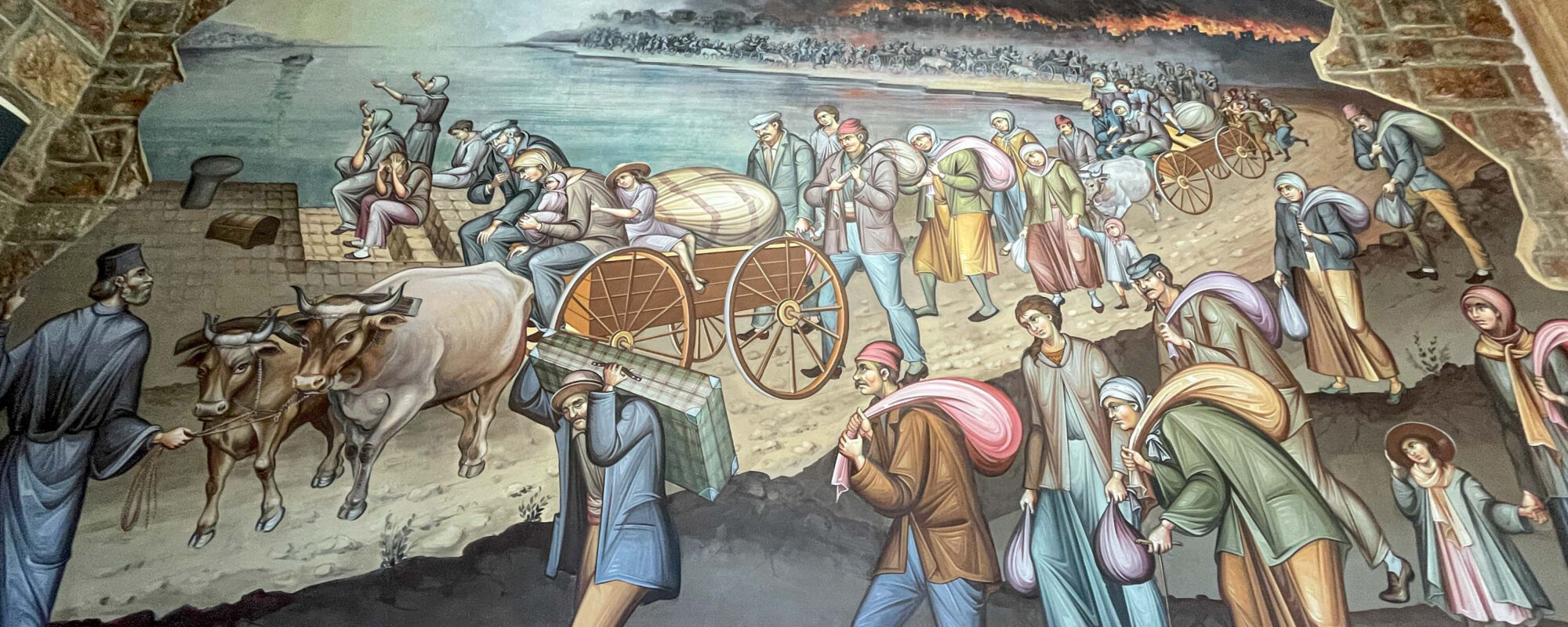

Páter Nektarios led me inside the cathedral, which is filled with beautiful frescoes painted by the Athenian hagiographer Michail Douzenakis. The vestibule is decorated with two main scenes. To the left of the door, “The Persecution” depicts sorrowful families bent under the weight of their belongings as they stream out of a city engulfed in flames.

On the right, a man wearing a fez stands in a rowboat carrying the icon of Agios Charalampos. The waves are stylized into blue and white spirals, and behind him is the landscape I saw every day across the sea (apénanti in Greek): a white city at the edge of Anatolia.

Páter Nektarios shared the miraculous story. Soon after the catastrophe, Agios Charalampos visited a Turkish boatman named Ali in a dream and commanded him to bring his icon from the abandoned church in Cesme to the refugee cathedral in Varvasi. Ali took the holy icon across the strait, delivering it to its new home. He then settled in Chios castle, an area inhabited by Turks.

I gazed at the large icon of Agios Charalampos with a long white beard, his head surrounded by a silver halo. Originally a priest from Asia Minor, he was subjected to all manner of torture, including burning, for professing his faith. Beside the icon in an ornate silver box is a relic of the saint that came from Smyrna, traveled to the United States and eventually ended up in Varvasi. Did residents see in his unending trials a reflection of their ancestors’ hardships?

The Cultural Association of Varvasi “The Lighthouse” Library was a hive of activity on the evening I visited. Kids played table tennis in the basement of the large building, shouting with joy as they scored. A Christmas tree twinkled on the main landing. President Georgia Chouli, her sister Kaiti Chouli and Erato Boulazeri welcomed me into an auditorium and ordered me tea.

Warm and bright-eyed, Georgia told me the history of The Lighthouse. It began as a lending library for schoolbooks. Since refugee families could not afford them, the older children of Varvasi asked wealthier islanders to donate textbooks their kids had finished using. At first the library was housed in neighborhood garages, with as many as 20 children crowding around a single book, Kaiti added. But in this way, they were able to educate themselves.

Since the early 1980s, the association has been housed in its current building, a gift from industrialist Eleftherios Karamanis. Today it hosts a range of extracurricular activities including traditional dance, painting, music and choir classes, as well as chess and table tennis. It also has theater and publishing groups, research and lending libraries, and a museum with artifacts from Asia Minor. “We don’t have computer labs or robotics,” Georgia said. “We try, for a few hours every day, to use our hands, our voices, to unglue ourselves and the kids from our screens.”

The Lighthouse aims to preserve the memory and traditions of Asia Minor Greeks. Together with other Anatolian associations, it actively represents the community on Chios and promotes Anatolian cuisine and culture. As its activities expanded, it linked itself with the island’s other tragedy. In 1976, it established regular ceremonies commemorating the Chios massacre at the abandoned village of Anavatos, where women leapt to their deaths to avoid disgrace.

Last October, on the eve of Oxi Day, a national holiday honoring Greece’s refusal of an Italian ultimatum and entry into World War II, The Lighthouse planned a performance highlighting the musical and dance traditions of Chios, Oinousses and Asia Minor. Called Enthymion or “Momento” on the occasion of the island’s 1822 and 1922 anniversaries, the show played at the Homerion Cultural Center to a full house.

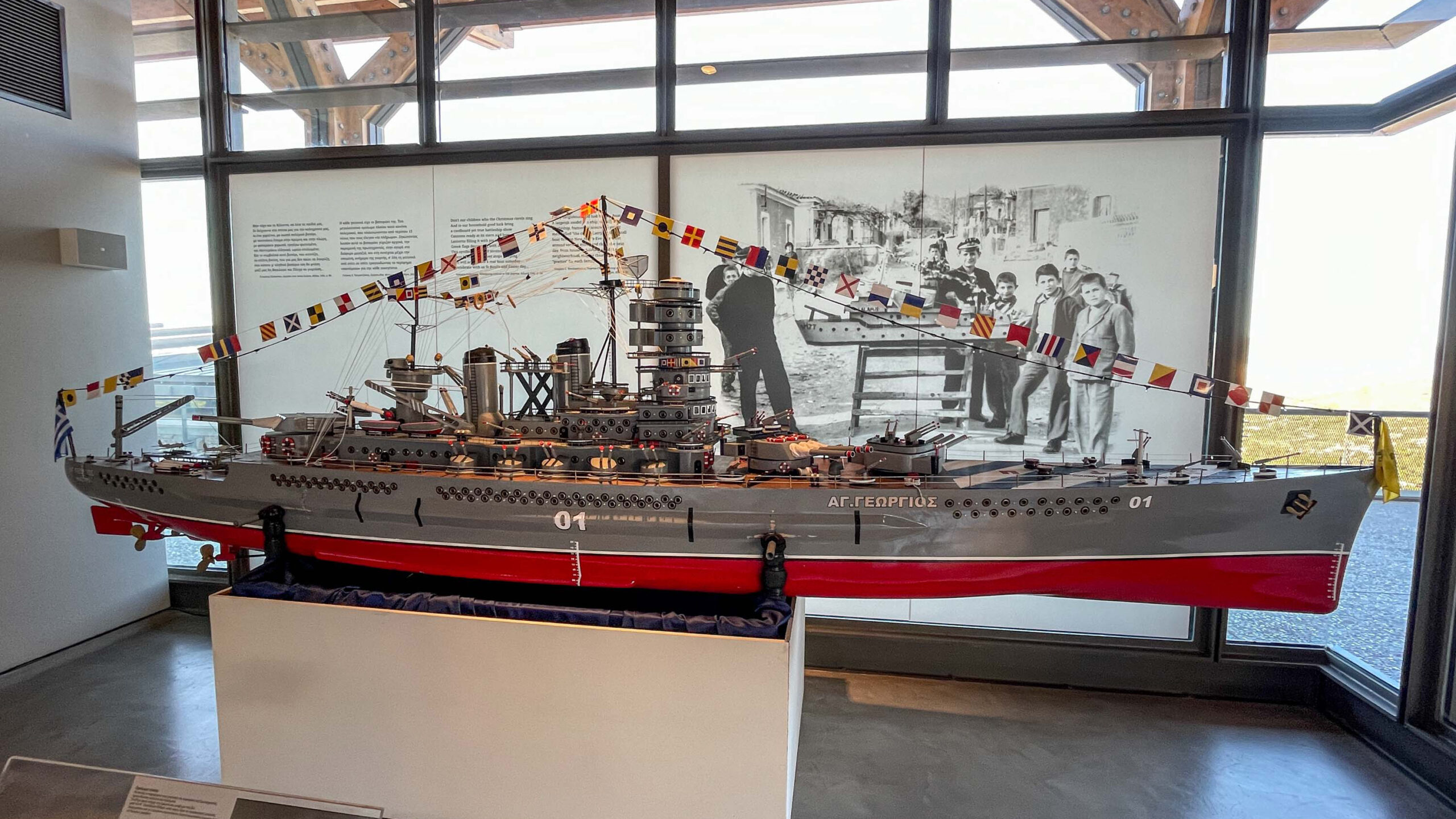

When I visited The Lighthouse, Georgia and her team were preparing to revive the New Year’s Eve custom of the Agios Vasileios steamers after a two-year hiatus due to the Covid pandemic. In this Smyrniot tradition, children construct elaborate model ships to carry from house to house while singing carols. The procession of the steamships was revived in Chios’s refugee neighborhoods after World War II, and this year, six ships competed.

I saw one of these battleships, the 5.5-meter-long Agios Georgios, on display at the Chios Mastic Museum’s temporary exhibition on the catastrophe. The wooden ship took some 4,000 euros and 10 months to build and was equipped with lights, electric radars and cannons. Georgia reflected on the importance of maintaining the island’s customs each year. “If it doesn’t happen, it’s lost,” she said. “The tradition isn’t the same afterwards; it becomes an enactment.”

The Lighthouse also organizes apénanti excursions every year. “For us, it’s a pilgrimage to the place where our grandparents lived,” Kaiti told me. “In the same way Athenians return to their villages, we feel our roots are there.

The legacy of the catastrophe

The refugees who restarted their lives in Greece made profound contributions to their new homeland. The shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis fled from Smyrna with his family at 16; Nobel Prize-winning poet George Seferis was born in Vourla (now Urla), a town between Izmir and Cesme. Asia Minor entrepreneurs also launched large industries in Greece like the Hellenic Powder and Cartridge Company (PYRKAL), Papadopoulos Biscuits and Cana Laboratories. Their descendants can be found throughout the country, as illustrated by the wealth of reportage, programming and scholarship that has been devoted to the events of 1922 over the past year.

In Athens, the Benaki Museum and the Centre for Asia Minor Studies launched a large exhibition, Asia Minor Hellenism: Heyday – Catastrophe – Displacement – Rebirth to mark the anniversary. Supported by Greek President Katerina Sakellaropoulou, the exhibit was accompanied by musical performances, film screenings, lectures and even a pop-up restaurant, Veggera in Smyrna, where chef Nena Ismirnoglou prepared a gastronomic tour of Anatolia.

The cities of Chania and Heraklion also launched exhibits focusing on the refugees who came to Crete in the wake of the disaster. I will explore how the population exchange affected Crete’s Christian and Muslim communities in a future dispatch.

Additionally, the think-tank Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP) initiated a five-year project in 2021 called HOMEACROSS to study the “material legacies” of the population exchange: urban and rural sites of displacement and resettlement in Attica and Izmir. Kalliopi Amygdalou, the project’s principal investigator and a Chios native, said in an interview with Kathimerini that Greece’s integration of over a million refugees is linked to the history of its infrastructure, modernization and the development of the Greek welfare state—a timely topic due to the Covid pandemic and energy crisis.

Even as Athens and Ankara continue to dispute maritime boundaries, militarization of the Aegean islands, natural gas exploration rights and Turkey’s continued occupation of northern Cyprus, residents of Varvasi emphasize the bonds they feel with their neighbors. “We have very friendly relationships with the people across the strait,” Kaiti Chouli told me. “We’re friends on Facebook, and sometimes we say, ‘We’re coming over tomorrow!’ Some of them know this is our grandparents’ home, and they’re very welcoming. The government and the people are completely different.” It’s a common refrain, one I’ve heard from Turks themselves.

But this cognitive dissonance creates its own difficulties. Since 1922, successive Turkish governments have pursued policies hostile to the Greek Orthodox minority remaining in Istanbul. Repeated targeting has made many Greeks wary whenever Turkey issues a new threat. “Sometimes you think maybe that’s not all just a joke,” former Chios Mayor Manolis Vournous said. “Or you feel awkward when you’re so comfortable with Turkish people, but then the public messages coming from Turkey don’t make you feel comfortable at all.”

A Turk I befriended in Izmir blamed the West for “making problems” for Turkey and Greece so that it could benefit from the Mediterranean’s rich natural resources. “Our citizens don’t see each other as enemies. If our countries were united, we’d do lots of collaborations,” he told me. “But imperialist countries want a weaker Greece and Turkey. France supports Greece in making a local problem a European issue. They want chaos so they can sell us military equipment.”

Chrysovalantis Stamelos told me that the internet and social media are making it harder to have open discussions about historical events in Izmir—a trend I’ve noticed in the United States as well. “Everyone has their echo chamber, and that’s very hard to break,” he said. “People before were much more open to dialogue because they didn’t have that fed to them.” It was troubling news: an unwillingness to entertain other viewpoints combined with an ignorance of the past doesn’t bode well for the future.

Throughout my travels in Greece, I’ve met countless descendants of Asia Minor refugees, and I have to admit I feel a certain kinship with them. Forced to start over in a new place, they are an open, enterprising people, proud of their homeland and no strangers to hard work.

When I visited the island of Oinousses for the feast day of Agios Nikolaos, I met Periklis and Tasoula Komninaris, descendants of 1922 refugees from Meli and Karaburun, just across the water. They own the town bakery, just as Periklis’s great-grandfather did in Karaburun. During the procession through the village with saint’s icon and relic, they wore Anatolian costumes and carried the navy-blue banner of the Oinousses Departments of Traditional Dance “I Sina.” They had prepared all the treats the municipality served after the church service.

I introduced myself and asked to learn more about their family story, and they welcomed me with open arms. Periklis drove me around the eastern part of the island to see the Asia Minor monument and rough stone houses where refugees lived when they first arrived, tending vineyards as they did apénanti. Tasoula invited me to join her at the bakery early the next morning to learn how to make xerotygana, a traditional Anatolian sweet.

She was already hard at work by the time I arrived, having filled three baking trays with thin strips of dough ready to be fried in olive oil. The warm kitchen decorated with family photos was a refuge from the early morning chill. She carefully explained each step, hunched over the trays with her wire-rimmed glasses sliding down her nose. I snapped dozens of photos, the aroma of fried dough and cinnamon making my mouth water. Before I left to catch the ferry to Chios, she packed me a box of freshly made xerotygana doused in honey, cinnamon and chopped almonds—her grandmother’s recipe—to take with me on the journey.

Top photo: Michail Douzenakis’s fresco “The Persecution,” depicting the expulsion of Greeks from Asia Minor in the narthex of Agios Charalampos church in Varvasi, Chiosr