A Brief History of the Institute of Current World Affairs

By Peter Martin, former Executive Director and Honorary Trustee

A person’s first encounter with the Institute of Current World Affairs (ICWA) is almost always a surprise. The Pulitzer Prize winners are announced, for example, and the winner for musical composition turns out to be Roger Reynolds, a professor at the University of California at San Diego. Creativity has a thousand sources, but one life-changing moment stands out in Reynolds’ past: Thirty years before, in his formative years, he had spent three years in Japan learning Japanese, living in the world of contemporary Japanese music, and writing and performing his own compositions as a fellow of the Institute of Current World Affairs.

After years of brutal warfare, Mozambique’s rebel RENAMO forces agree to a cease-fire with the FRELIMO government. The United Nations needs negotiators of great judgment and patience to travel to Maputo and carry out peace talks leading to elections and the establishment of a stable government. A Harvard-trained attorney named Samuel Levy, pursuing a rising career with a prestigious New York law firm, offers to resign his position and spend however long it takes to help make peace. The UN organizers look behind the Harvard degree and the New York credentials to find—a painstaking and caring negotiator with fluent Portuguese who had lived in Mozambique for more than a year as an ICWA fellow when the fighting between RENAMO and the government’s FRELIMO forces was at its bitter worst. Levy spends two years in Maputo, seeing the negotiations through to a successful conclusion.

After decades of isolation behind a Stalinist wall of rigid Marxism, Albania finally admits a tiny handful of Western journalists. The first Tirana byline on a front-page lead story in the New York Times is that of David Binder, an ICWA fellow who spent years gaining an understanding of Eastern Europe in the 1950s.

Constant pressure for democracy in Kenya is applied to President Daniel arap Moi by a persistent and hard-headed American ambassador, Smith Hempstone. Moi finally gives in and holds multiparty elections. As a young journalist, Ambassador Hempstone learned about East African life, history and customs as a fellow of the Institute of Current World Affairs.

The President of the United States proposes a new direction for American relations with China. For analysis, the White House calls on Doak Barnett, a senior fellow of the Brookings Institution who carried out his first intensive study of Chinese culture and politics from 1947 to 1950 as a fellow of the Institute of Current World Affairs.

These moments occur dozens of times a year, almost inevitably provoking the question, “The Institute of What?” That is because ICWA, despite the fact that it is nearly 100 years old, has always done its work quietly, and individual by individual; counting current fellows in the field, the cumulative total stands at a few over 165.

When people first understand the idea and purpose behind the institute, they are surprised at both its simplicity and its complexity—as if they were encountering their first water wheel, safety pin or Brancusi sculpture. The institute seeks out young individuals of high intelligence and promise, frees them from the routine of their professional lives for at least two years and gives them the time and resources to explore the world and fulfill that promise through a self-designed program of study, thought and writing.

Except within the expansive boundaries of “current world affairs,” and with the geographic limitation that fellows must study outside the United States, the institute believes in broad limits. It does not set minimum educational standards. It does not discriminate between men and women, between married and unmarried, between specialist and generalist. It pays no attention to color or creed unless color or creed is integral to a fellow’s work.

There are some things ICWA insists upon, however. To give our investment many decades to pay off, fellows must be young—under 36 at the time of application. The institute does not underwrite the getting of academic degrees (although many fellows go on to seek advanced degrees). It does not fund the writing of books (although many fellows go on to write books). Why? We feel that advanced-degree candidates who have had thesis topics approved by a committee, or authors who have had book projects accepted by a publisher, are basically “filling in the blanks.” The institute wants fellows who are free to follow their noses into any and all interesting avenues of inquiry, into and out of culs de sac, even into making mistakes (and, of course, learning from them).

ICWA invests in people, not projects. It requires those people to be exceptional, well-balanced, self-disciplined, open and mature enough to accept the life-change and mind-change that is often the result of living on your own and overseas as an institute fellow.

Like the water wheel, the safety pin and Brancusi sculptures, the institute did not just happen.

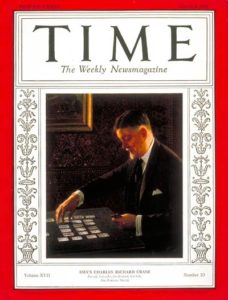

It grew out of the relationship between three turn-of-the-century men: Charles Crane, his son John, and Walter S. Rogers. Charles Crane was one of two inheritors of the Chicago company that owed its success to America’s enthusiasm for indoor plumbing, but he was far more interested in international affairs than in bathtubs. Even as a young man working for the family company, he began traveling the world, seeking understanding and self-enlightenment. He was, without knowing it, the first fellow of the Institute of Current World Affairs.

In the early 20th century, Crane became a friend and supporter of Woodrow Wilson—and, in many ways, served as Wilson’s international eyes and ears. Wilson sent Crane to Russia as a member of the Root Commission to size up the situation after the October Revolution. When Wilson went to Versailles in 1919, Crane was part of the delegation. As part of the Versailles process, Crane was appointed to an allied commission to travel through the Middle East to determine the fate of segments of the defeated Ottoman Empire under the policy of “self-determination of nations.”

The British and the French immediately withdrew from the commission; by secret negotiation and treaty, they had already determined who was going to get what in the Middle East. The commission, which became known as the “King-Crane Commission” (“King” was Henry C. King, president of Oberlin College)—went anyway, and reported that leaders in the Middle East wanted a US mandate over the region until they could decide the shape and direction of their national futures. At the insistence of the French and British, the report was suppressed; still, Crane was appointed US minister to China in 1920. The King-Crane Commission report was finally “leaked” in a special edition of Editor & Publisher magazine in 1922, after the Wilson administration had ended.

That marked the end of Crane’s “public” career, but it had absolutely no effect on his inbred international curiosity and love of travel. The King-Crane experience had focused his attention on the Middle East, and he was particularly fascinated by “the peninsula of Arabia as the home and natural habitat of prophets… I wanted to get as near as possible to the conditions of life out of which appears every now and then a great prophet.”

Since the King-Crane days, he had followed the career of Abdul-Aziz ibn Saud, founder of the kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and was eager to meet him. In February, 1931, he got his wish. Accompanied by George Antonius, an early fellow of the institute who served as translator and rapporteur (and later wrote The Arab Awakening, a seminal book heralding the birth of contemporary Arab nationalism), Crane spent five days in Jiddah, lunching, dining and exchanging ideas with King Abdul-Aziz.

They also exchanged gifts. The King presented Crane with an assortment of rugs, daggers, swords—and in that ultimate Arabian gesture of friendship, asked Crane to step outside where six magnificent horses were held by handlers. Crane chose two Arabian mares for shipment back to his summer home in Woods Hole, Massachusetts.

For his part, Crane asked the King to give him one of his sons to be educated in the United States. Ibn Saud refused. A Western education tended to wean a young man from the customs and traditions of his country, he said, and that was a risk he did not care to run. Crane then asked whether the King had explored the possibility of using artesian wells to irrigate desert agriculture. Crane said he had used this technique to grow figs and dates at his California ranch.

Ibn Saud said he had thought about that, but had felt reluctant to embark upon costly drilling until he could get men with the necessary technical knowledge to investigate the probability of finding water. Here was Crane’s opportunity. He had employed a mining engineer named Karl S. Twitchell to prospect for water in California, he said, and had loaned him to the Imam of Yemen for similar exploration. He offered Twitchell to Ibn Saud. Ibn Saud accepted.

After months of exploration, Twitchell had good news and bad. He had found the site of a possible gold mine, he said, but little underground water. However, he reported to the King, there were many signs of petroleum, perhaps in commercially exploitable quantities. Ibn Saud wrote to his friend Crane to report Twitchell’s findings. He was unused to the ways of Western business, he said in his letter, so he had a proposal: If Crane would handle the business end of the petroleum development, Ibn Saud would split the profits, 50-50.

Crane declined, saying that his motivation was friendship, not commercial gain. And, he went on:

_______________________________________________________________

Although I am hesitant about offering advice on any particular project, on the basis of my observations I do feel that in general it is better for a nation to develop its own resources with its own talent and money, or, if these are inadequate, with a minimum of such aid from abroad. Certainly the granting to aliens of monopolies or extensive concessions not infrequently leads to both internal and external difficulties.

— Letter from Charles O. Crane to King Abdul-Aziz ibn Saud

_______________________________________________________________

The King neglected Crane’s advice. Instead, he asked Twitchell whether he could “find capital which would be interested in testing the possibilities of oil.” Twitchell got in touch with the Standard Oil Company of California—and the rest, as they say, is history.

The second half of the Crane-Rogers Foundation, Walter Rogers, was a Chicago newspaperman who put himself through night law school and became fascinated in the early 1900s with the infant science of telecommunications. As the century turned, he was working for the Crane Company. When Charles Crane left to begin his world travels in earnest, he took Rogers with him. With young John Crane, Rogers and the elder Crane traveled in China, eastern Europe and Russia.

During World War I, when President Wilson became fed up with what he considered the inaccurate reporting of the war by the mainstream press, he appointed Rogers to inaugurate a telegraphic news service for the rapid and accurate transmission of war information and analysis. After the war, Rogers was also part of the US delegation at Versailles, witness this account by fellow delegate Henry Allen Moe:

_______________________________________________________________

At Versailles, after World War I, President Wilson had forbidden anybody to speak to him at the conference table. But when the question of mandating the Caroline Islands to Japan came up, you violated the rule and suggested to the President that he make a reservation on Yap. And the President, despite his anger at your interruption, did make a reservation on Yap. Then, after the session had ended, the President sent for you and asked for an explanation. You told him that the importance of Yap arose from its cable connections — from the United States to the old Dutch East Indies via Guam, and from Yap to Shanghai.

— Letter from the late Henry Allen Moe, ICWA Trustee and founder of the Guggenheim fellowships, to Walter S. Rogers, founding executive director of the Institute of Current World Affairs.

_______________________________________________________________

After the Great War, Rogers and John Crane settled in Prague, capital of the newly created nation of Czechoslovakia. There they established an independent press service called the Mutual News Exchange. It was that experience, as John Crane later recalled, that “soon convinced us that the effective interpretation of emerging developments would require a modern intellectual training as rigorous and as worldly as that which had made of [Robert] Morrison of Peking and [James David] Bourchier of Bulgaria the supreme embodiment of the scholar-journalist.”

Supported by a $1 million trust fund established by Charles Crane, the Institute of Current World Affairs was incorporated in New York State in 1925. At the time, the idea was to recruit and support 10 or 15 men (in those days, the idea of signing on women never came up), wise in the ways of particular areas of the world, to serve as the core corps of the Mutual News Exchange. Those men, free to travel and learn, free of any ties to governments or commercial organizations, would constitute a living endowment of wisdom, expertise and detached judgment for commerce, government, the academy and serious journalism. Rogers became executive director of the institute and occupied that position for 34 years, until his retirement in 1959.

Charles Crane died in 1939, Walter Rogers in 1965 and John Crane in 1986; as a commemorative gesture, the institute is now also known as the Crane-Rogers Foundation.

The institute never fulfilled the initial vision of its founders—for the best of reasons: As quickly as John Crane and Walter Rogers found people with the requisite talent, dispatched them to various parts of the world, and watched them grow into full familiarity with their fields and their areas, others found them. And hired them. So Rogers spent his career in the rewarding business of seeking out people to take their places. Having been a journalist and a lawyer himself, he found many journalists and quite a few lawyers. He came to spend nearly six months out of every year traveling across the country and the world, looking for fellows. Often without advance notice, he would appear at a city editor’s desk, a politician’s office or a college president’s anteroom.

_______________________________________________________________

He came to Dartmouth at least once a year. He’d always come to the office looking just as if he’d walked out of a cornfield and put the hoe down, you know. He was very sort of l9th-century rural in appearance, but he had a delightful, almost whimsical way of drawing you out. We sometimes would leave my office and go down to the porch of the Hanover Inn. We’d sit out there in old-fashioned rocking chairs and kick things around for a while. I looked forward to his visits, and I think it’s fair to say I always took something away from them. We talked about how you got at things, how you judged people, how you used a particular person’s talents well and intelligently.

The first conversation that I remember with him was about the valedictorian at commencement in the spring of ’46, a lad named Dick Morse, who was the son of a very close friend of mine on the Dartmouth faculty. Morse had caught his fancy…

— John Sloan Dickey, president of Dartmouth College 1944-1970

_______________________________________________________________

Sooner or later, no matter who he was talking to, Rogers would eventually bring the conversation around to which people were doing what. Which young lawyer in town was making people uncomfortable? Who had written the newspaper story people were talking about? Which young businessman had found a better way to do things? Whose head was above the trenches? A name would be dropped, a note would be taken and Rogers’ assessment process would begin.

In another compartment of his mind, Rogers kept a working atlas of the world after tomorrow. Terms like “Third World” and “underdeveloped nations” lay far ahead, but the future importance of “backward” Russia, “colonial” India, “sleepy” Latin America, “war-torn” China and “darkest” Africa were as real to Rogers as the warped economics of Europe after the Great War. When he had finished his preliminary evaluation of a young person’s potential, he often began matching that person with an area of the world whose time was coming.

Education levels meant much less than promise. In 1947, Rogers encountered an energetic young newspaperman named Albert Ravenholt, who had worked in China and Burma during World War II, first with the Red Cross and then as a reporter for the United Press. Rogers liked the cut of the Ravenholt jib and decided to take him—and his wife Marjorie—on, despite the fact that Ravenholt had no college degree.

_______________________________________________________________

My boyhood through high school was spent on a farm in northwestern Wisconsin. Since the age of 14 I have supported myself and, whenever possible, helped my family. Because funds were limited, I earned only two quarters’ credit toward a degree in college. Instead, to learn a trade, I became apprenticed to a chef in a large hotel and… took night courses in creative writing, economics and history. The experience in a hotel kitchen gave me an opportunity later to ship as cook on a Swedish freighter which stopped at a number of ports in the Orient…

— Letter from Albert Ravenholt to Walter S. Rogers

_______________________________________________________________

Rogers sent Ravenholt to meet an old friend, Owen Lattimore, at Johns Hopkins University. Lattimore heartily approved of the appointment. “Being an old maverick myself, my interest was particularly aroused by the fact that he does not have a college education. Your idea… reminds me that I was in a similar situation when the Social Science Research Council, giving me a grant for a year in Manchuria, similarly decided first to send me for a couple of years to the Department of Anthropology at Harvard—not to get a degree but just to acquaint myself with the academic way of working.”

Lattimore said he would be glad to have Ravenholt at Johns Hopkins—but feared he would not get the language training he needed. “I would urge him to look very carefully into the area studies program at Harvard in which John Fairbank is active…” With his lifelong friend Theodore (“Teddy”) White, Ravenholt spent a year at Harvard studying Chinese history and language, and taking advantage of invitations from Curator Louis Lyons to sit in on the Nieman fellows programs.

His report card from Fairbank: “Al Ravenholt has just written an excellent final examination in our Far Eastern history course, and I should like to take this occasion to tell you how much we have enjoyed his as well as Marjorie’s presence here this year… From my own personal point of view I gained greatly from his presence in our seminar discussions, since he is the most live-minded questioner of speakers that we have had.”

Ravenholt went on to a distinguished lifetime career as an Asianist, covering the Communist takeover of mainland China, quizzing Mao and Ho Chi Minh about political philosophy, providing a farmer’s-eye perspective on the “Green Revolution” activities of the International Rice Research Institute in the Philippines—and, taking advantage of his farming background, establishing some of the Philippines’ most successful mango orchards and the state of Washington’s most productive wine-grape vineyards. His wife Marjorie initiated, promoted and managed the Magsaysay Awards for political leadership throughout Asia and the Pacific. As was the case with Ravenholt, the unpredictable was a predictable element of Rogers’ fellow-finding.

_______________________________________________________________

My first awareness that there was something called the Institute of Current World Affairs or a man named Walter Rogers came in 1953, two years after I’d broken in as a cub reporter for the St. Louis PostDispatch. I’d done a few good stories, won a couple of bylines, but mainly I was learning my way around the beats—police headquarters, the federal courts, the board of education. One winter morning as I was about to leave for the civil courts building, the phone rang on my desk.

“This is Walter Rogers in New York,” said the voice on the other end. “I’m with the Institute of Current World Affairs. It’s been suggested that you might benefit from spending two years in sub-Saharan Africa. Are you interested?”

“Yes,” I said. “But I know very little about Africa.”

“Well, why don’t you come to New York and talk about it?”

— Peter Bird Martin, writer and senior editor for TIME magazine (1955-70), a founding editor of Money Magazine (1970-78)

_______________________________________________________________

In 1951, Rogers took a giant step closer to achieving his original objective for the Institute by creating a separate sister organization called the American Universities Field Staff (AUFS). Supported by the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations and the membership fees of as many as 20 US colleges, the AUFS was governed by a board made up of presidents, chancellors and other top executives of the member universities. Its teaching personnel consisted of a career corps of permanent world scholars, living in their regions of specialization overseas and returning periodically to the United States to serve temporarily as adjunct professors of international affairs at the member institutions.

The AUFS “Associates,” as they were called, were almost by definition academics with “a modern intellectual training as rigorous and as worldly as that which had made of Morrison of Peking and Bourchier of Bulgaria the supreme embodiment of the scholar-journalist.” Most of them had been fellows of the Institute of Current World Affairs.

Since the creation of AUFS seemed to fulfill the original purpose of Rogers’ and John Crane’s Mutual News Exchange, Rogers tried to persuade the board of ICWA to merge its endowment and activities into the AUFS. The ICWA members and governors rarely opposed Rogers, but this time they resisted. They felt that ICWA had developed a distinct purpose of its own: the experiential and intellectual growth of the fellows themselves. Furthermore, they were not prepared to dilute their governance by the addition of a large number of university presidents.

So the two organizations separated—but not by much. They shared office space in Manhattan, and Rogers tended to appoint as ICWA fellows people who showed promise of becoming AUFS associates. Still, the institute established a strong identity of its own—so strong, that from time to time other organizations, such as the Ford Foundation and the General Service Foundation, made grants to enable the institute to focus its unique capacity for individual development on specific professions or topics—on journalists, for example, in a special Ford program in the early and mid-l950s, or on forests, in a Forest & Society program established in the mid-1970s by John Miller Musser of the General Service Foundation.

As a matter of policy, institute fellows are explicitly forbidden to accept any intelligence-gathering assignment from anyone.

_______________________________________________________________

During the course of my living in India, I was variously mistaken for a left-over British civil servant, a Swedish missionary, a Russian engineer, and an American photographer, and once I was hailed (by what, I assure you, was a highly superstitious old woman) as “a gift of God.” Ordinarily, I explained myself as “an American student” and let it go at that. Whenever there was someone who officially pressed me further, or someone whom I thought would appreciate it, I called myself a fellow of the Institute of Current World Affairs. I explained the best I could.

Among responses, I remember the raised eyebrows and incredulous smile of an Indian police officer as I crossed over from the Pakistan Punjab at a border checkpost, and I remember the second secretary at the Communist Chinese Embassy in New Delhi, whose gaze gradually refocused, as I explained the Institute, into the Oriental stare-through.

But I also remember the saffron-robed, white-bearded pandit in a town in Madras state, wagging his head and smiling with bright eyes as I explained, then exclaiming, “What a beautiful idea! Be so kind, who is this gentleman Walter Rajah?”

— Walter Friedenberg, Scripps-Howard, Washington, DC

_______________________________________________________________

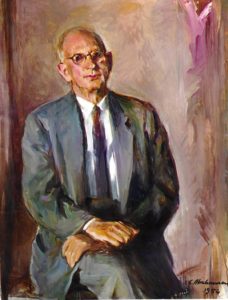

The lawyer side of Rogers showed itself strongly in the 1930s, and most particularly in 1934, a year after the United States at last recognized the government of the Soviet Union. He won the permission of the Russian Information Office to send a law student to Moscow, then turned to a distinguished Harvard professor of international law, Manley O. Hudson, for a candidate. Hudson tapped a bright young student named John Hazard, who was just finishing his law degree.

As Hazard later wrote (in the third person) in his memoirs, “Hazard was well aware of the risks in going to a revolutionary country which he had seen in 1930 during the first leg of a trip around the world with three Yale classmates. At that time, he had decided Russia was a hopelessly poor, disorganized and undisciplined country. He even wrote his sister that he never wanted to see it again…

“The decision was not easy. He saw two more of his favorite Harvard professors. Both encouraged him to accept, and by Monday morning he was ready to tell Hudson that he would accept the nomination. After several interviews with forbidding [ICWA] board members, the most frightening of whom was Henry Allen Moe, the world-famous director of the Guggenheim Foundation, by August 1934 the young hopeful Hazard was on his way. He knew no Russian, no Russian history and no Marxist theory. He knew only that a career of uniqueness might result…”

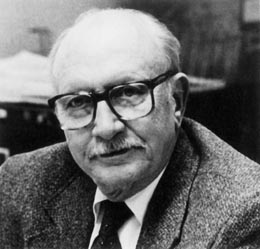

He was right. John learned Russian and Russian law from Stalinist lecturers who, he later told the current executive director, “merely paused in the anteroom to wash the blood of purges from their hands.” Back in the United States, Hazard went on to teach at Columbia University, help found the Russian Institute there (now the Harriman Institute), and become one of America’s most distinguished—and most approachable and most likeable and most unpretentious—professors of international law.

Rogers scored another legal coup in 1938, when he persuaded a young attorney who had just passed the Oklahoma bar exam to go to Japan, learn Japanese and get a Japanese law degree. The young lawyer was Thomas Blakemore—and Blakemore had the kind of ICWA nerve it takes to accept such a challenge. Armed with a letter of introduction to one of Japan’s leading jurists, Blakemore described his incredible project to the eminent man in Tokyo in 1939. “To his everlasting credit,” Blakemore wrote in the jurist’s obituary a few years ago, “he never cracked a smile, but hastily dispatched me to the best language class in Tokyo.”

Blakemore did not quite finish his law studies. In October 1941, on the advice of one of his law professors, he left Japan for a “holiday” in the United States. After Pearl Harbor he spent the war years in a US Army uniform, and followed General MacArthur to Tokyo as a legal assistant to the Civil Affairs division of the US occupation. He helped rewrite the Japanese constitution and civil code, and took the Japanese bar exam. He passed, thereby becoming the first non-Japanese admitted to full legal practice in Japan (and the last; the Japanese later closed the exam to foreigners).

With gusto and Oklahoma charm, he practiced for decades as half of the Tokyo law firm of Blakemore & Mitsuki. Taking advantage of a rarely exercised fishing law, he worked as a conservationist to bring trout back to the fished-out streams of Japan. And, on a small farm he purchased on the outskirts of Tokyo with some of his legal fees, he experimented so successfully with dwarf varieties of fruit trees that he eventually succeeded a former Japanese prime minister as president of the Japanese Dwarf Fruit Tree Growers’ Association.

From 1938 to 1941 (and again from 1946 to l948, and again in 1950), Rogers sent Phillips Talbot, a sometime reporter for the Chicago Daily News, to India. And in 1947 he launched Richard Nolte, with Yale and Oxford degrees in international and Arabic studies, on an investigation of Islamic law and the Middle East.

In 1967, Talbot and Nolte juxtaposed in a most curious way. Nolte had just arrived in Cairo to become United States Ambassador to the United Arab Republic; Talbot had become United States Ambassador to Greece. The Six-Day War erupted, and the institute fellow in Cairo safely shepherded American travelers and businessmen out of Egypt by ship. The institute fellow in Athens saw to it that they were given shelter across the Mediterranean in Greece.

Talbot served as the first executive director of the American Universities Field Staff, was appointed by President Kennedy as assistant secretary of state for Near Eastern and South Asian affairs, went on to become president of the Asia Society in New York and Asia specialist for the Aspen Institute and other organizations. Nolte succeeded Walter Rogers as the executive director of the Institute of Current World Affairs, serving from 1959 until his retirement in 1978.

Among those in the Rogers succession was Peter Martin, who accepted Walter Rogers’ invitation to live and learn in sub-Saharan Africa from 1953 to 1955. He watched and wrote about the invention of apartheid in South Africa, the dehumanization of blacks in the Belgian Congo, and the resistance of the Ashanti people of the northern Gold Coast to domination by Kwame Nkrumah’s coastal people in what was about to become Ghana. He then spent 23 years as a writer, senior editor and magazine inventor at Time Incorporated, leaving in 1978 to take up the executive directorships of both the institute and the American Universities Field Staff.

Today, ICWA carries on the tradition begun in 1925. It includes the understanding that even when a fellowship is finished, the fellow isn’t. Fellowships provide bonds of belonging that continue for life. Familial ties of common interest and experience tend to bind together former fellows, trustees, members and other people associated with the institute in a continuing and mutually beneficial relationship.

Is it possible to “sum up” the Institute of Current World Affairs? Probably not. The “sum” keeps growing, year by year, fellow by fellow, and the institute is much more than the sum of its parts. A former fellow, Jeffrey Steingarten, spoke for himself and for all fellows a few years back:

_______________________________________________________________

“The Institute of Current World Affairs is, as far as I can tell, the only creature of its kind. It is not for everyone. There are more direct ways for a journalist to tackle a subject in depth, for a scholar with a well defined idea to bring it to fruition, for a young person with a wanderlust to see the world. For us, the fellows who need to discover for ourselves the source of whatever originality has been granted to us, there is not, and never will be, anything but the institute.”

_______________________________________________________________

And, as is only right, Walter Rogers has the last word, describing the vision that motivated him in creating the institute:

_______________________________________________________________

It was of a small, independent corps, each member of which would be (or on the way to becoming) mature intellectually, morally and emotionally; a person of integrity, including a self-respect that brooks no wavering when confronted with dubious choices, risk or abuse; a person not intimidated by education or riches or position—or press releases; a person in no sense pedestrian-minded but on the contrary possessed of a free-ranging mind; a human person readily making friends at many levels and justly winning their respect; a person with pride that is well salted by grains of humility; a person devoted to his[her] accepted purpose and to his[her] colleagues.

— Memorandum to institute members and trustees from Walter Rogers, 1958.

_______________________________________________________________