21 January, 2016

Ahmed Naji is a 30-year-old journalist and novelist. When we meet for dinner in mid-December, he faces a lawsuit for “infringing on public decency” that might land him in prison for two years. State prosecutors are throwing the book at him for a sexually charged chapter of his Cairo novel Using Life, which was republished in the state-owned literary review Akhbar Al-Adb.

One reader keeled over from reading it. “[His] heartbeat fluctuated, his blood pressure dropped and he became severely ill,” according to legal documents.[i] In 2014, the man in question, 65-year-old lawyer Hany Salah Tawfik, complained to the state prosecutor’s office. It didn’t matter that government censors had already approved Naji’s novel, which was published earlier in the year by the joint Lebanese/Egyptian/Tunisian publishing house Tanweer—printed in Beirut and exported to Egypt, it is sold throughout Cairo. Egyptian law allows third parties to file grievances against purported transgressors of Islamic values called Hisba in Islamic law. Historically, private citizens have used this practice as a form of censorship; the targets have been controversial personalities, from heterodox scholars to the superstar comedian Bassem Youssef. Article 67 of Egypt’s 2014 constitution protects artists from Hisba suits. Nonetheless the state prosecutor reserves right to pursue cases, such as the one against Naji and the editor-in-chief of Akhbar Al-Adb.

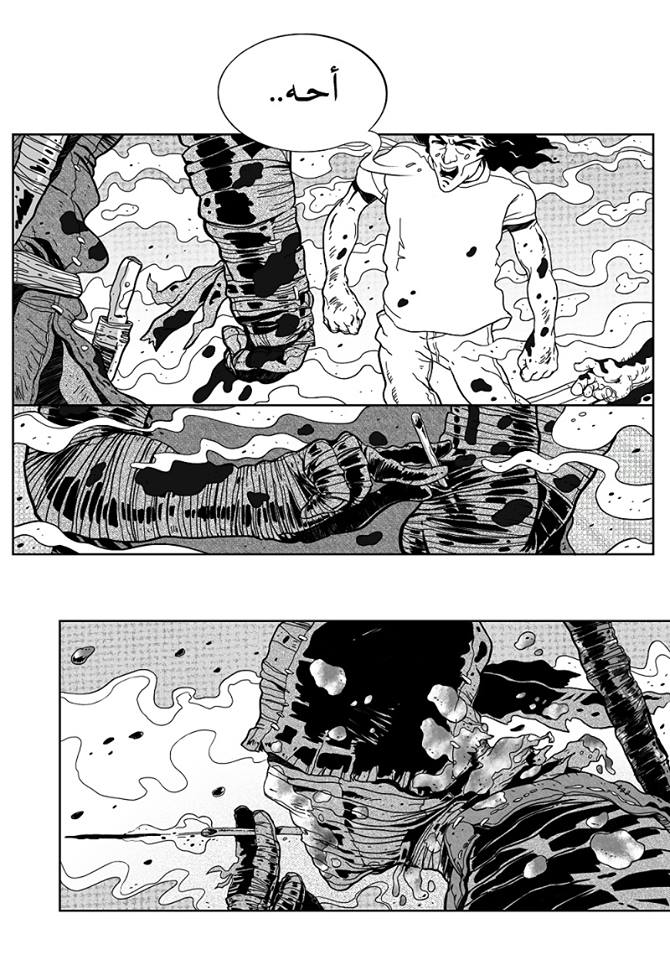

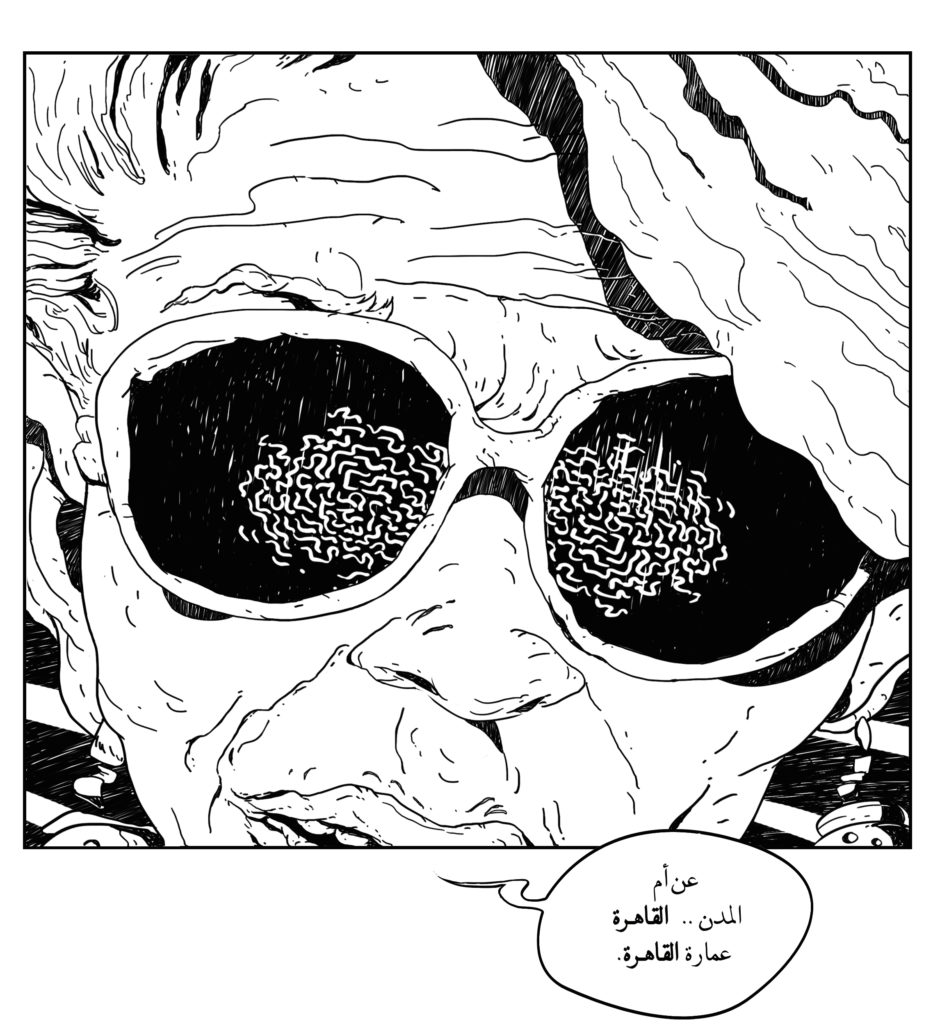

In Using Life, an experimental novel that fuses prose and comics, Naji describes sex and drugs matter-of-factly. The narrative is hardly more “obscene” than others on Cairo bookstands. “I plunged my tongue into her vagina. I drank too much that night, I drank until I felt parched,” Naji writes in Arabic, in the section that stirred the disgruntled reader’s heart. “The sex is slow and steady. I put it in her back, put my fingers in her mouth,” Naji continues. “Then I got up from the bed, took off the condom, and flung the used [rubber] in the trash. I smiled at her, and my cellphone rang.”

On November 14, the Bulaq Abu Elli Criminal Court held its first session about the chapter’s pornographic nature. “The accused disseminated written materials that exude sexual lust and fleeting pleasures, lending out his pen and his mind to violate the sanctity of public morals and good character, instigating harlotry, in open disregard of decency because he presents scenes that portray a brazen encounter of the two sexes,” the prosecutors wrote in their memo to the court.[ii] News reports quoted the prosecutor stating: “As soon as [Ahmed Naji] published the product of his poisonous pen, it reached out to those near and far, minors as well as adults. In so doing, he became like flies that see nothing but filth, and on filth he casts light and points cameras, until chaos prevails and the straw catches fire.”[iii] Curiously, the state prosecutor treated Naji’s fictional text as a journalistic piece of writing. Investigations into the author for smoking hashish and having extramarital sex, as described in the chapter, ensued.

After speaking with Naji and researching legal precedents, I could not decide whether it exemplified the ridiculousness of Egyptian law or shifting social mores. At first the case seemed like a fluke, one that had disrupted the life of this young artist but signified nothing more than a prudish prosecutor’s desire to make a name for himself.

But as the winter went on, the trial appeared to be part of a wider, clumsy crackdown on artistic practice in Cairo. Each incident offered up particularities that shed light upon the lack of protections for artists and the indiscriminate enforcement of laws. Authorities shuttered a world-renowned contemporary art space and a publishing house. Downtown cafes known to be activists’ hangouts were arbitrarily closed. Prominent novelists and journalists faced censorship or incarceration.

Considered collectively, a broader narrative emerged of a republic where art was perhaps the last remaining threat to the status quo. Since 2013, the state has outlawed public protest and political movements both Islamist and secular, while targeting an assortment of opposition voices. As the fifth anniversary of the 2011 uprising rolled around, the haphazard attack on cultural institutions exposed the state’s tacit acknowledgement that art holds out the power to topple a regime.

“A Season in Hell”

I meet Ahmed Naji at Estoril, a cozy downtown tavern, which makes an appearance in Using Life. When Naji and I open the wooden door into the smoky room of full tables on a brisk Monday evening, Ayman the waiter shakes my hand and tells me he is mad. He has been saving the table every Thursday for Surti and me, but we haven’t shown in a month. The restaurant is fully booked tonight, he says with a laugh. He sits Naji and me down at table marked Reserved.

Naji happens to know two journalists sitting at the table beside us. We schmooze with them, and one says that he will visit Naji in prison, which elicits chuckles from all. After more banter, Naji slips to the bathroom. He comes back and drops his keys, phone, wallet, L&Ms and lighter on the red and yellow tablecloth. He has been running around all day and hasn’t eaten since breakfast. Ayman returns with spicy cheese dip and arugula salad on the house, and we each order a steak and a beer.

The prosecutor’s office summoned Naji in April 2015, he tells me. Lawyers went to the meeting in his stead, and for the next six months, authorities investigated the republished chapter of Using Life. At that time, Naji stayed hush about the case, which he thought would peter out long before reaching court. Then one October morning, a journalist from Al-Shorouk newspaper phoned him, asking for his opinion. The case was going forward.

Our steaks arrive from the kitchen. As we cut into the meat with paltry knives, Naji talks about the defense’s strategy. “I didn’t attend the court,” he says. “I would be in the cage.” Once in that cage, the judge might decide to keep him in holding until he reached a ruling. So for the December 12 session, the lawyers enlisted three authors of heft to testify on his behalf—novelist Sonallah Ibrahim, former Minister of Culture Gaber Asfour, and Writers’ Union President Mohamed Salmawy.

I wondered if the impetus for the case was connected to Naji’s political writings or Akhbar Al-Adb’s liberal bent. “No,” says Naji. “The prosecutors are just stupid and right wing, and they are more Salafi than the Salafis. And for them, it’s the kind of case that gives them the opportunity to appear in the image of the public moral guards and the white knights and the guy who protects the family values and blah blah blah.”

That prosecutors can put a writer on trial suggests an endemic problem, one intimately tied to the government’s survival tactics. Naji’s lawyer Nasser Amin also pointed out that the authorities pursue moralistic assaults against young artists to rally their base and prove their virtuousness.[iv] “It seems that censorship of literature is best understood as a barometer of regime confidence. The more confident a regime is, the less likely it will engage in ridiculous things like censoring Naji’s novel,” Elliott Colla, a scholar of Arab literature at Georgetown University and my longtime mentor, told International Business Times.[v]

Samia Mehrez, director of the American University of Cairo’s Center for Translation Studies, offered a different rationale. She described the case against Naji as an “inside job” started by someone within the literary field with a grudge, someone who wants to stir “a little scare, a little scandal.”

But the two perspectives are not mutually exclusive. Naji’s circumstance is at once singular and tied to a long history of artists fighting for the right to offend. Under the regimes of Mubarak, Morsi, and Sisi, state prosecutors have taken artists to task for exercising that right. The arbitrary application of the law and the capacity for legal recourse against a particular artist compose a classic form of theater here. Because once a grudge leads to a lawsuit, all the actors have to play their parts: the prosecutor, the judge, etc.

“After all these years, I can no longer take these episodes seriously as an indication of censorship,” said Mehrez. “For us to go out and say look they’re censoring, I think it’s a fallacy. Because you can go out and buy another ten books and find a similar lexicon, if not worse, where nobody is attacking the writers. There are many examples. It’s not like Ahmed Naji wrote the un-writeable.”

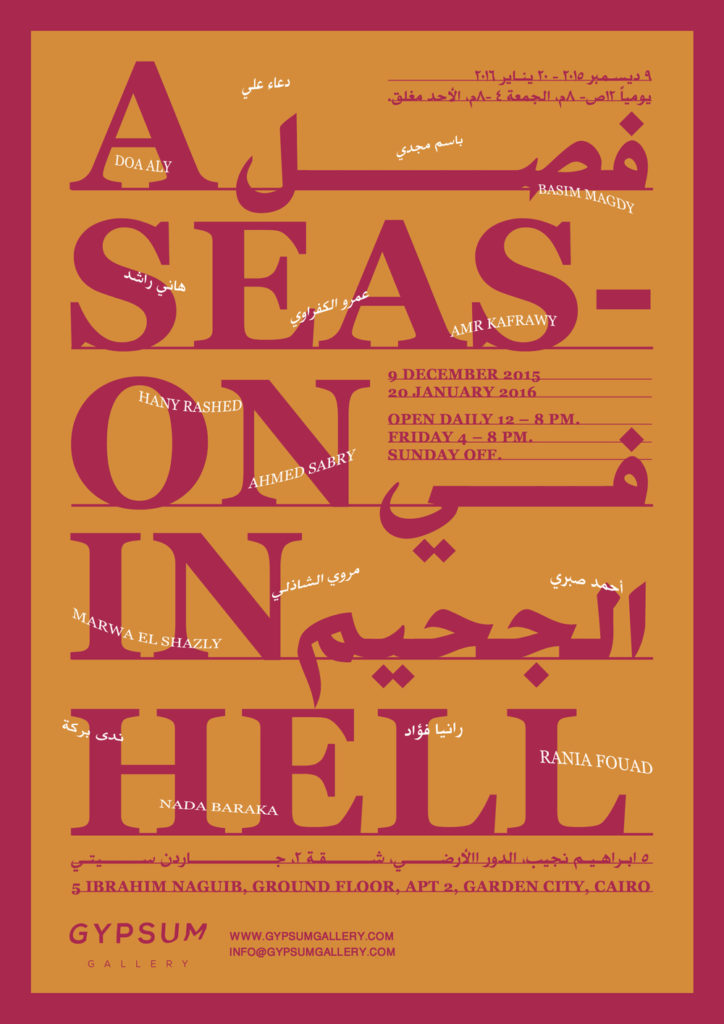

Lately Naji has been too busy to write, having hoped to finish a book of short stories by year’s end. I saw him jotting down notes at a symposium about the Egyptian surrealist arts movement at the American University in Cairo in late November. A week later, he was hanging out at the opening of a group show at Gypsum Gallery, in Cairo’s Garden City neighborhood, where much of his novel is set. The exhibition was titled, “A Season in Hell.”

“Increasingly Toward Darkness”

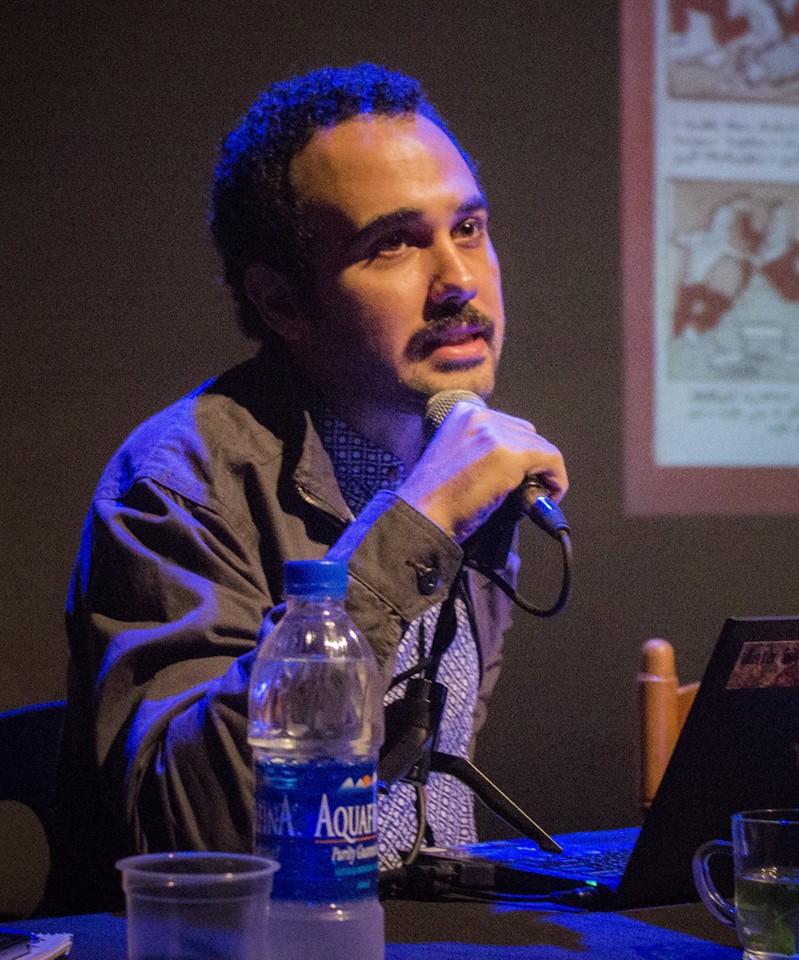

I had first met Naji in early November at Townhouse Gallery’s Rawabet Theater. We served on a panel together at Egypt Comix Week, which was themed around free expression. Naji delivered an impassioned lecture on the history of Arab comics for children and adults. “From the 1930’s to 1948, there was more freedom to publish comics than we see right now,” he told the audience. “It was easy for people to make new comics and publish without restrictions.” In fact, I had purchased Naji’s Using Life from Townhouse’s bookstore, where it was displayed alongside T-shirts and mugs with Ayman Al-Zorkany’s drawings from the novel.

On December 29, twenty officials from an array of government agencies raided Townhouse Gallery in downtown Cairo.[vi] Archival documents, two computers, and other office supplies were confiscated.[vii] Its gallery, theater, library, bookshop, and auxiliary spaces were shuttered. Yet it was far from clear why the Censorship Authority, Tax Authority and National Security Agency had taken such interest in the internationally acclaimed art institution. Townhouse had been visited by authorities previously, but not on this scale and the venue had never actually been closed. Initial reports suggested that officials had turned up without any reason or search warrant. Subsequently, Major General Yassin Abdel Barri, chairman of the West Cairo District—basically the city council—said that the closure pertained to licensing “irregularities.”[viii]

As the anniversary of the 2011 revolution grew closer, Townhouse’s predicament fit a larger pattern. In November, the Censorship Authority raided the Contemporary Image Collective, a downtown arts initiative. In an attempt to keep the story out of the news, CIC downplayed the incident as an administrative quirk.[ix] A new film center had been unable to acquire authorization to operate. By mid-January, another downtown arts space has been raided in reaction to a licensing issue.[x] Naji drew attention to “the siege of Egyptian cultural institutions” in a column for the popular daily Al-Masry Al-Youm,[xi] “It’s as if the plan is to marshal Egypt’s social and physical environment increasingly toward darkness,” wrote Naji.

The raid on Townhouse as well as a progressive publishing house and other art spaces downtown seemed connected to the government’s fear of protests in the lead up to the fifth anniversary of the 2011 uprising.[xii] “It definitely has to do with January 25, otherwise Townhouse would have been open by now,” said one person knowledgeable about the raid, who asked to not be named. Townhouse had informally served as a hideout for protesters dodging arrests during the January 2011 uprising, given the art space’s proximity to Tahrir Square and downtown’s primary thoroughfares, the person added.

Founded 16 years ago, Townhouse has revolutionized Cairo’s contemporary art scene. Townhouse’s downtown complex serves as a conduit for Egyptian artists to connect with international museums and markets. At the same time, it is a gathering space for academics and activists for local causes, lines of inquiry, and cultural experimentation in all of its varied forms. In this way, Townhouse serves as a shadow culture ministry, albeit on a much smaller scale. Contrasting more traditional design displayed in official cultural palaces, the space fosters contemporary arts practice in Egypt and has stimulated the formation of other like-minded establishments.

So what do artists and curators make of Townhouse’s closing? At a recent panel on the Art Economy of Egypt at the Binational Fulbright Commission in Egypt, I posed this question to two founders of independent art spaces. Hamdy Reda of Artellewa, brushed off “the official problems” at Townhouse as relating to the downtown gallery’s lack of an emergency exit. “I have three exits,” he said of Artellewa, as the hundred-plus person crowd chuckled in their red velvet seats.

Eschewing such glibness, Moataz Nasreldin of Darb 1718 discussed the chilling effect of Townhouse’s closure. “We are all facing the same,” he said, describing how tax authorities and angry spectators have caused him headaches since Darb 1718’s establishment eight years ago. “We keep on going against all odds, and we’re never going to stop,” he said, his deep voice bellowing through the auditorium of the Ministry of Culture’s Gezira Art Center. Yet Nasreldin went on to imply that the very occurrence of a raid suggests Townhouse’s culpability. “There must be something unusual to send seven different authorities at the same day to check on this—there much be something wrong,” he said. He insinuated that there was indeed an administrative hiccup, but the suppression of others suggests that the shutdown is political.

A day before Townhouse’s closure, the Censorship Authority stormed Merit publishing house, rifling through its offices and arresting a staff member for several hours. A lapse in its publishing license was ostensibly the cause. Publisher Mohamed Hashem, however, speculated that the upcoming book launch of Ashraf Abdel Shafy’s Vodka, which focuses on local media corruption, was the authorities’ motivation.[xiii] The downtown publishing house is also known to have been a place of refuge for demonstrators during the 2011 revolt. Speaking on the Fulbright panel, artist Khaled Hafez suggested that the raid spurred from Merit’s hosting of a public reading for Palestinian poet Ashraf Fayadh; a Saudi Arabian court found Fayadh guilty of forsaking Islam and ruled that he be beheaded. On January 14, Merit went ahead with an event as part of a global solidarity campaign with the condemned poet, who remains in a Saudi prison. “We will expose the executioners in Saudi Arabia and maintain our solidarity with Ashraf Fayadh,” Hashem, Merit’s founder, posted online. “We will continue to dream of bread, freedom, and social justice. And you won’t see us terrorized!”[xiv]

Additionally, authorities are monitoring other gathering spaces throughout central Cairo, variously shutting down street cafes in prime locations. “Even the coffee shops downtown [have been] attacked by Egyptian security, because they want downtown emptied before the anniversary of the revolution,” said Mohamed El-Baaly of Sefsafa Publishing House. “Anyone who is working on or around free art, or freedom of speech in the arts or cultural sector, is now in danger. Yesterday was Merit and Townhouse, and tomorrow we don’t know who.”

“Between Reality and Illusion”

Censorship is not unique to Egypt or the contemporary Middle East. The tension between art and the state has existed as long as these institutions themselves and continually reappears in new forms. Plato’s arguments in favor of censorship, for example, could easily describe the Egyptian state’s current rationale. Plato wrote, “Then the first thing will be to establish a censorship of the writers of fiction, and let the censors receive any tale of fiction which is good, and reject the bad…”

In Egypt, the state continues to reject authors that counter official narratives, not only through official censors working in bureaucratic offices but also by way of backhanded attacks. Consider Alaa Al-Aswany, the world-famous dentist-cum-novelist and author of the Yacoubian Building. A high-profile supporter of the 2011 uprising against Hosni Mubarak and, similarly, a cheerleader for the military’s ouster of President Mohammed Morsi in 2013, the author found that the space for criticism had shrunk by summer 2014.[xv] He quickly fell out of favor with official circles. “[The] authority now is in a situation that they are afraid of any logic[al] voice. Alaa Al-Aswany is one of the logic[al] voices, so they want to put him outside of the picture,” says Naji.

Local newspapers refuse to publish Al-Aswany’s columns. He no longer appears on state television programs.[xvi] Still based in Cairo, the best-selling writer is essentially persona non-grata. In December, authorities cancelled a public event he had planned to hold in Alexandria on “Conspiracy Theory: Between Reality and Illusion.”

Unlike Naji, no famous writers have come out in support of Alaa Al-Aswany, an outsider who has come to dominate Egypt’s literary field. “He’s in a double bind,” says Mehrez, the literary scholar. “This is the card that [the authorities] played against Alaa at the moment when they know no one will come to his rescue… He’s a dead duck.”

Other writers have come under fire, too. In February 2014, the privately owned newspaper Al-Shorouk banned columnist Belal Fadl, known for his biting satire, after rejecting an article he wrote that criticized President Sisi.[xvii] His novels continue to be sold at Shorouk’s chain of bookstores throughout Egypt, but Fadl now lives in New York.

Journalists have faced even harsher censorship. In November, the investigative reporter and eminent human rights defender Hossam Bahgat made international headlines when he was detained for two days for his story about a covered-up coup attempt. Similarly, Sinai-specialist Ismail Iskandarani has been arrested for over a month days after landing in Hourgada airport from Turkey. Several more journalists and editors have been arrested in mid-January.

All these cases speak to a lack of rights. Writers “know they have no protections,” says Mehrez. “The law is against them and can be used against them at any moment, all of them. It just depends who is unlucky or who has a grudge against you. The laws are there to put every single writer in [a] struggle for every single thing they write…It can be political or religious… Everything they write is out there to implicate them, because the law is there to implicate.”

Naji has written journalistic articles against Sisi. Even though he has gotten threats in response his critical writing about the government, he claims that is not the reason for the lawsuit. Says Naji, “This is normal, and I’m used to it.”

“Congrats on Your Innocence”

On January 2, the judge acquitted Ahmed Naji. The author smiled broadly as his lawyer Nasser Amin clenched a cigar between his lips. The Association for Free Thought and Expression, a local watchdog that lent another attorney to represent Naji, heralded the win as a “bright spot in the heart of a crazy campaign against houses of art, freedom, and creativity.”[xviii] His Facebook wall quickly filled with scores of joyous messages. “Congrats on your innocence,” one friend posted.

Ten days later, Naji received an alarming update. The prosecutor would retry his case in a higher court.[xix] I reached Nasser Amin by phone. A distinguished human right advocate who defended filmmaker Youssef Chahine two decades ago, Amin told me that the right to free expression is enshrined in the 2014 constitution. I asked him if the case against Naji was connected to the broader assault on arts and cultural institutions across Cairo. “The authorities have no sympathy for intellectuals, artists or creators,” Amin said. “The authorities are offended.”

[i] Teresse Pepe. “‘Literature’ is on Trial in Egypt,” Mada Masr, 13 November 2015. http://www.madamasr.com/opinion/culture/%E2%80%98literature%E2%80%99-trial-egypt

[ii] I have done my own translation for part of this quote, but also drew on the translation in this article: Ahmed Wael. “The Crime of Expression,” Correspondents, 5 November 2015. http://www.correspondents.org/node/7013

[iii] Translation by Ehab Abdel-Hamid, Facebook, 12 November 2015. https://www.facebook.com/ehab.abdelhamid.writer/posts/10154752560067588?fref=nf. For an extract of the original Arabic memorandum, see: “Innocence for Ahmed Naji in the Case of the ‘Sex Article,’” Dot Misr, 2 January 2016. http://www.dotmsr.com/details/براءة-الكاتب-أحمد-ناجي-في-قضية-المقال-الجنسي

[iv] Maram Mazen. “Egypt Lawyer Challenges Law that Says Writers Can Be Jailed,” Asssociated Press, 12 December 2015. http://bigstory.ap.org/article/3f3938dc4dd242ada036f308eb409d93/egypt-lawyer-challenges-law-says-writers-can-be-jailed

[v] Farid Farid. “Egypt has Satire in its Sights as Wife-Swapping Novel and Scantily-Clad Singers Censored,” International Business Times, 9 November 2015. http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/egypt-has-satire-its-sights-wife-swapping-novel-scantily-clad-singers-censored-1527827

[vi] Townhouse Gallery, “Rawabet Theater Closed After Interagency Raid,” Mada Masr, 29 December 2015. http://www.madamasr.com/news/culture/townhouse-gallery-rawabet-theater-closed-after-interagency-raid

[vii] “Egypt: ANHRI Condemns Raid on Townhouse Gallery and Rawabet Theater,” Arab Network for Human Rights Information, 29 December 2015. http://anhri.net/?p=157393&lang=en

[viii] Amira El-Sharkawy. “West Cairo District: Closure of Townhouse Gallery is Because of Irregularities, Nothing to do with the Anniversary of January 25,” Al-Ahram, 3 January 2016. http://gate.ahram.org.eg/News/836895.aspx

[ix] “Studio Emad Eddin Inspected by Authorities, Operations Continue as Normal.” Mada Masr, 14 January 2015. http://www.madamasr.com/news/studio-emad-eddin-inspected-authorities-operations-continue-normal

[x] Maram Mazan, “Egyptian Officials Raid Art House, Publishing House,” AP/Business Insider, 30 December 2015. http://www.businessinsider.com/ap-egyptian-officials-raid-art-house-publishing-house-2015-12

[xi] Ahmed Naji. “Darkness Descends on Townhouse,” Al-Masry Al-Youm, 7 January 2016. http://www.almasryalyoum.com/news/details/869907

[xii] Kareem Fahim and Amina Ismail. “Egypt Shuts Art Venues Amid Signs of Clampdown,” New York Times, 30 December 2015. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/30/world/middleeast/egypt-shuts-arts-venues-amid-signs-of-clampdown.html

[xiii] “Update: Prosecution Orders Release of Merit Publishing House Staff Member, Summons Founder,” Mada Masr, 29 December 2015. http://www.madamasr.com/news/culture/update-prosecution-orders-release-merit-publishing-house-staff-member-summons-founder

[xiv] Marcia Lynx Qualey. “Cairo’s Merit Publishing House, Townhouse Gallery Raided; One Merit Staffer Arrested, Released,” Arab Literature in English, 29 December 2015. http://arablit.org/2015/12/29/merit-publishing-house-townhouse-gallery-raided-one-merit-staffer-arrested/

[xv] Hend Kortam. “Criticism and difference of opinion no longer allowed: Alaa Al Aswany,” Daily News Egypt, 24 June 2014. http://www.dailynewsegypt.com/2014/06/24/criticism-difference-opinion-longer-allowed-alaa-al-aswany/

[xvi] Marcia Lynx Qualey. “Egypt Shuts Down Novelist Alaa Al-Aswany’s Public Event and Media Work,” The Guardian, 11 December 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/dec/11/egypt-shuts-down-novelist-alaa-al-aswanys-public-event-and-media-work

[xvii] Mayy El Sheikh. “A Voice of Dissent in Egypt Is Muffled, but Not Silent,” New York Times, 2 May 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/03/world/middleeast/an-egyptian-voice-of-dissent-is-muffled-but-not-silenced.html

[xviii] “Naji’s Innocence a Bright Spot in the Heart of a Crazy Campaign Against Houses of Art, Freedom, and Creativity,” The Association for Free Thought and Expression, 3 January 2016. http://afteegypt.org/freedom_creativity/2016/01/03/11343-afteegypt.html

[xix] “Egypt Author Faces Retrial over Sexually Explicit Material,” AP, 12 January 2016. http://bigstory.ap.org/article/e4f539f8f71c4bcda600fc88f4e5a36a/egypt-author-faces-retrial-over-sexually-explicit-material