Living and traveling on a sailboat is often about suffering gracefully and making good decisions in bad situations. I think that’s part of the reason I choose to sail the coasts of Latin America and the Caribbean. My partner Josh and I get to share the challenges of a seabound experience with others who work in salt waters every day.

Climate change threatens the coastal way of life, both on the estuary where I grew up in New Hampshire, and in Latin America—as a result of carbon largely emitted by others. In my struggle with this disparity, I raise sails to lower my own footprint. I travel by sea to learn what people saw before we dropped anchor, and what they hope will come. What do they know about the natural systems that help them survive on the edge? What are the small ways in which people adapt to change when they get battered by the sea—the very thing keeping them afloat? I hope to learn how people keep fighting for what they value, even as the sea rises.

These are the unheard stories from the front lines of the climate battle—the edge of the ocean. My journey will be taxing and my perspective biased, but I hope to give to you the real stories of change on the shores of Latin America. Thank you for giving us ‘adventure scientists’ a shot. We hope to live up to the name of our boat, Oleada: the Uprising.

“We need to jibe NOW!” I yell as an animal the size of our 39-foot sailboat crashes into the water a few feet off our starboard beam.

We’re sailing in open water in the Pacific Ocean, off the west coast of Mexico’s Baja peninsula. The wind is blowing a steady twenty knots out of the north, so we cut the engine and surf down rolling five foot ocean swells. With the wind coming over my right shoulder, I’m at a good angle to keep speed and stability, and as I watch the GPS screen that tracks our location using satellites, we nearly reach ten knots. A record so far for the trip! This is exciting and fun sailing. But it also means that a quick change in direction is difficult and dangerous if we don’t give it our full attention.

As is the case if your copilot is awestruck by a breaching whale. A second time, the whale bursts out of the water and into the wind. “WHOA!” Josh, my partner, exclaims, laughing at the incongruous site: when all you see during the day are sea birds from a distance, a surprise explosion from a massive mammal a few feet away while hauling at the top speed of your little boat gets the blood pumping.

Whale breaches are dumbfounding. A mammal weighing between 15 to 35 tons, which normally suspends itself in liquid, summons the ambition and strength to plow upward with such force that it moves nearly two-thirds of those 70,000 pounds into the open air. Once there, it executes the most enormously impressive belly flop, complete with a whitewater explosion visible for miles. It makes all the hairs stand up on the back of my neck. Whale biologists guess they may do this to show off, scratch their backs, get rid of parasites, find each other, herd fish, or, best of all, just for fun. Like many explanations in animal behavior, it is most likely a combination of some or all of these. But this does not affect the electrifying rush of seeing a whole whale appear without warning to shatter the trance above the waterline. It is both terrifying and exhilarating because it simply doesn’t seem possible—both the event and the fact that you were there to see your distant mammal cousin perform this practical act of effusive joy.

These events are not for sailors to capture with a camera unless strangely lucky. Under sail with only two people, all hands are devoted to the boat and safety aboard. Even leaving the camera handy could not prepare us for magical wildlife events, and even with the camera in hand, there is a reason that wildlife photographers are the best paid photo artists. This does not stop us from trying, but if not stymied by safety or lack of photo skills, we are often halted by our own awe.

But at this moment, marveling must give way to action, since we can tell that this jumping whale is absorbed in its frolicking and we need to give it some space. At the wheel, I gently point the nose of the boat away from the wind so we are now headed dead downwind. Josh cranks hard on the main sheet, using the leverage from the handle and the winch, to bring the boom to the center of the boat. The main sheet is the rope attached to the boom. It controls the position of the main sail—which currently functions as our source of propulsion through the water. Josh must yard this in rapidly so when the wind catches the opposite side of the sail as I turn, the rope is tight and the boom doesn’t slam to the other side of the boat with extra slack. Sailors have ripped booms off their boats or broken their masts doing this wrong. Despite the increase in the wind and the chop on the water, our boat, Oleada, spins easily into the wind, and Josh deftly and calmly moves the main sail, then the jib (the forward sail to the starboard (right) side of the boat. Now the wind is coming over my left shoulder and the whale is back there too. I breathe a sigh of relief before I realize that our new direction means that we are heeled over so much that we are dipping the bottom of the jib in the water, and the cockpit feels like a double black diamond ski slope. Josh takes the wheel as I use all of my strength and speed to wind the jib up so that we have less sail area, bringing us back to a more comfortable angle—but still taking crashing waves over the top side of the deck.

Tonight we’ll sail through the night to reach our destination, Cedros Island. We are aimed for Cedros because it’s supposedly one of the most sustainable small-scale fisheries in the world—and a reasonable place to stop on our southern pilgrimage to the tip of the peninsula.

I don’t exactly love sailing overnight, but there are no other good anchorages between our starting point, San Quintín, and the island. Overnight passages on a sailboat require that one person stay at the helm at all hours, so Josh and I take turns sleeping. Because we have an autopilot on the boat, we can set a course (for example, 180 degrees, which is directly south) and, unless there is too much wind, which would overpower the electronic steering, we just have to be awake and looking for lights or other hazards. Lights could be other boats (usually fishing boats) or giant cargo ships. Hazards can be whales (which don’t breach at night, phew, but are easily identified downwind by their stinky fish breath,) crab traps that can get wrapped around our propeller, or rafts of kelp that can snare the rudder.

Clouds roll in and we start the engine as the wind dies. Throughout the night, the loud growl of our 50-horsepower diesel tractor motor is the only sound. When I take my two-hour naps, I sleep in the rear bed of the boat, called the quarter berth. It’s just big enough for one person. I put in earplugs and sleep soundly only a few feet from the engine. This is the original motor on the boat, a 1978 Perkins. We have a 50 gallon fuel tank, but the engine sips about half a gallon per hour when we motor at six knots. We try to motor as little as possible, but it eases the stress at night. Managing both the main sail and the jib alone in the dark can feel overwhelming if the wind picks up or shifts.

When I’m on watch, the water looks inky black except for the reflection of the light from the top of our mast, 60 feet above the waterline. It casts a cool, eerie glow out into the water. Based on our shifts, I have the coveted sunrise watch. I peer and squint into the slightest light of day. Are those clouds? Or islands? Steep and jagged Cedros Island comes into view like the knobby dorsal hump of a Gray whale.

The sun breaks the morning clouds and the boat comes alive. Josh and I clamber around on deck, walking up and down the four steep stairs from the cockpit into the cabin. Josh makes coffee on the galley stove as I tidy different ropes on the cabin top. At one point while fiddling with the jib, I feel so frustrated and sleep deprived that I consider crying. But the ocean immediately responds with dolphins. And it’s impossible to cry in the company of dolphins. They’re about my size, and they pump and glide just inches under the bow. I lean over the rail and we look at each other, curious. Then they dive and are gone.

We have a simple breakfast of yam mashed with cinnamon and toasted nuts as we motor past the steep northern tip of the island and down the eastern side, noting two small encampments that serve as seasonal homes for fishermen on the shore. As I eat, I feel the fatigue of the night set in. Dropping our anchor in calm, turquoise water about halfway down the 20-mile length of the island, I feel too tired to be relieved.

We launch the dinghy using the spinnaker halyard, the rope that brings sails up and down, but doesn’t control them side to side. A simple bridle attaches by three points to the dinghy so we can lift it over the lifelines and lower it gently-ish into the water. Now I can row to shore and explore in my state of exhaustion. The water is FULL of sea lions! They seemed playful and curious, but I’m aware that they greatly outnumber me.

I row to the beach, and as a gentle wave pushes me onto the pebbly shore, three snoozing seals open two-and-a-half of their collective eyes and continue to enjoy the sun. To get to a canyon, I walk through an elephant seal gauntlet. These dudes looked grumpy at best. Elephant seals are in the “earless seal” family (a classification, they still have internal ears), an ironic name given the 24-hour cacophony that ensues from this beach for all to hear. They create everything from farting grunts and belches to banshee-esque screams. All day, all night.

It feels great to be back in the desert. I lived for 10 years in the red desert in Moab, UT, and I spent many days wandering deserted canyons. It’s an environment in which I feel at home—despite being on an island in the Pacific, I recognize the desert cousins of many plants, blooming furiously to take advantage of a mild, moist winter.

Back at the boat, we prepare the bonito we caught just as we rounded the northern corner of the island. We trail two lures on line and a spool behind the boat, and we mostly catch seaweed. But this morning a beautiful, mackerel-like fish with horizontal black stripes and iridescent blue on its head caught our cedar plug. The cedar plug is just a hook protruding from a tapered cedar dowel, the simplest of lures. Now, the red meat from this fish serves as lunch.

As we sit in the cockpit in the sun, enjoying the calm anchorage in the afternoon and the first warm rays on our skin since San Diego, a bright yellow panga motors into view from the north. The panga is a simple, open boat, with a tall bow, powered with an outboard engine. In the late 1960s, Yamaha designed the boat in a new material, fiberglass, for access to shallow water and an easy ride over ocean chop. This inexpensive skiff, named for a type of fish (genus Pangasius) caught in coastal Asian waters, is now ubiquitous throughout much of the world. The panga before us is piled four-deep with lobster traps. I squint at his bow. Is that a refrigerator? Indeed, at a 45 degree angle, lying on its side, is a white, full-size refrigerator. He motors slowly to the bow of Oleada.

The fisherman standing at the back, with his dark brown skin and a perfect space between his two white front teeth, asks if I speak Spanish, and I respond yes. I wait a moment to learn his agenda. Nothing. I smile. I wonder why he came over, so I figure I will start with his name, and I give him mine. Eduardo deftly maneuvers his 20-foot boat close to the stern.

I ask Eduardo if he fishes here and lives here, to which he replies that he does. He lives at the fish camp from September until February, and has done so every year for 27 years. There is only one town on Cedros Island, and the fish camps are utilitarian assemblies of wood and metal for temporary living. The racket of elephant seals continues, and Eduardo comments that this is the first year that the elephant seals have come to this part of the island. His style is thoughtful, pensive.

I asked about our fish—is it a bonito?

“Stripes and a blue head?” he asked.

“Yes!” I exclaim. He nods. Bonito. But it’s not bonito season, he adds. Right now they catch mackerel, abalone, and lobster. Bonito and tuna are more common in December.

Since he has seen this island for 27 years, my interest is piqued. Without any leading words like “weather” or “climate,” I ask, is it different now here, or the same?

He turns his eyes to the sky and purses his lips, carefully considering my question. I lean forward.

Narrowing his eyes, he replies, “Different.”

“There are far fewer lobster now,” he says. “This year, from the effects of El Niño, the water is warmer, which is good for lobster, but generally there are far fewer now.”

His gaze stretches to the shore as he speaks, sifting through his memory. “Much has changed,” he continues. “For example, in 1997, there were three kinds of abalone: white, red, and black. That winter we had an El Niño, and the black—they disappeared.”

“Disappeared?” I respond, surprised.

“Completely,” he answers.

We chat more about life on the island (this day is the last day for a regulated lobster season for the year,) and then he pauses before saying something I have heard before as a gentle way to move on.

Okaaayy, YEEESSeeka,” he said, as if pondering my name as a way to both process our interaction and close our conversation.

Thank you for the visit, I call as he putters slowly away, and he laughs and recedes around the next corner. With only a few simple questions, this man tied to the cycles of climate and weather recalled the changes to which he needed to adapt. He also affirms for me that when we approach remote places from the sea, we fuel a curiosity that brings interesting people into our lives.

I forgot to ask him about the refrigerator. It was mostly likely powered by propane and used to keep his catch cool throughout the day. Even though we saw him in the early afternoon, he had pulled up all of his traps and he was bringing his catch to the only town on the island.

The Cedros Island fishery runs as a cooperative and has so since sometime between 1922 and 1943 (I found varying dates.) This is a long time. A cooperative allows fishermen to jointly harvest, market, and price their product. This way they can pool their catch to better access new markets and gain bargaining and purchase power. Nobel laureate Elinor Ostrom, the famed proponent of collaboration in economic markets, cited Cedros as an example of her broader framework that exalted the benefit of the commons. A cooperative is community-based, rewards hard work, fosters accountability, and those that function best are fair and rapid in enforcement of their own rules. Even Eduardo’s calm, thoughtful manner seemed to reflect those principles.

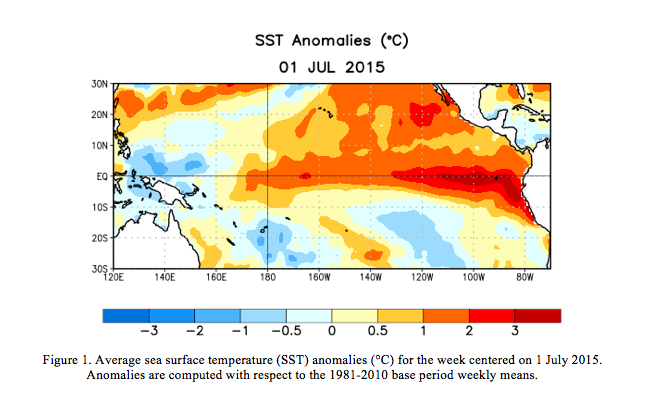

But what of the black abalone? To Eduardo, the abalone because of El Niño, the natural and cyclical weather phenomenon created by warmer-than-usual water in the Pacific at the equator. This warm water is driven by a slackening in the equatorial trade winds. Warm surface water that usually gets blown west to the south Pacific can now seep back to the east. Peruvian fishermen noticed the warm water around Christmas in the late 1800s, thus naming it “El Niño” after the baby Jesus. In 1997, El Niño was credited with disastrous hurricanes in the Caribbean and Pacific and a horrendous winter for northeastern North America, among other weather challenges.

Climate change appears to drive the frequency and severity of El Niños. A brief explanation of how this works: the ocean is a lot of water (H2O), absorbed carbon dioxide (CO2) and heat (energy!), and it has been absorbing over 90 percent of the extra carbon dioxide and heat we humans have added to the atmosphere since 1955 (we went from 280 parts per million of CO2 to 402 parts per million, ppm, today.) If you add heat and/or carbon dioxide to water, it expands. When we’re talking about a lot of water, like the Pacific, the heat becomes energy in the form of currents, eddies, and storms.

For example, hurricanes gain strength with the constant heat and moisture from open water, and they start to lose their energy once over land, in part because they can no longer draw warmth (energy) from the ocean. The hurricane season therefore ends as the water cools for the winter in both the Pacific and the Atlantic. But El Niño keeps the water warmer longer in the Pacific, and this has a global weather (energy) impact.

NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, declared in April that El Niño is officially here for 2015—although Eduardo could have told us that back in December, because he was seeing more lobsters and fewer big fish. Back in 1997, he also knew the fishery was different and the water was warmer, and, it seemed to him, a permanent change occurred as the result of that difference.

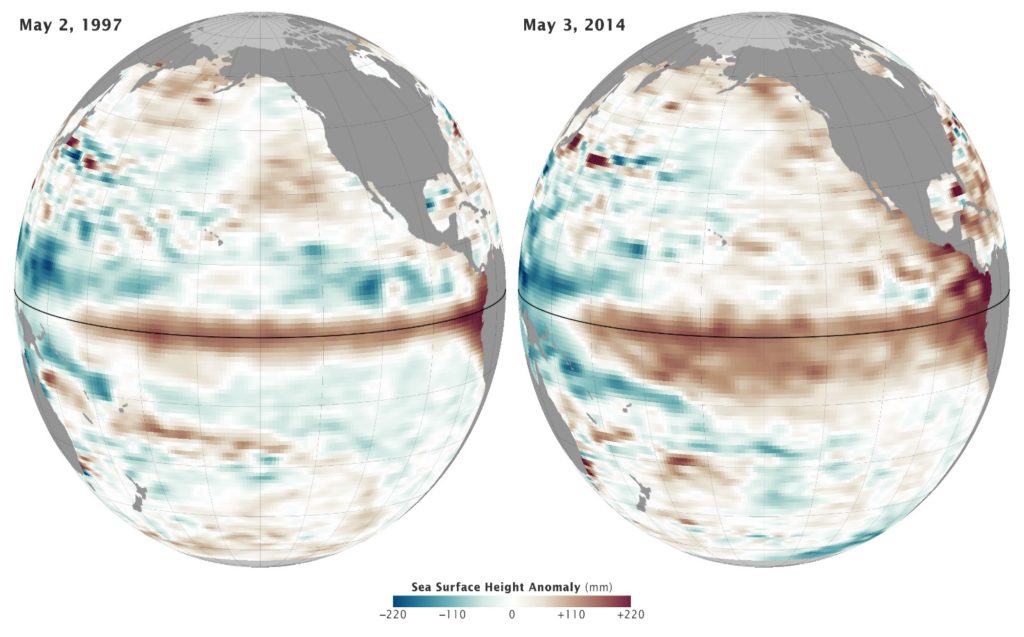

This graphic from NASA shows what El Niño looks like from a satellite that measures sea level height. Sea level height indicates increased warmth because, as the water heats up, it expands and rises. The molecules in warm water are farther apart than those in cooler water and therefore take up more space. Notice that NASA compares this image from 2014 with an image from 1997, the El Niño during which the black abalone disappeared.

Back to the mysterious, rapid and complete disappearance of an entire species from Cedros. If you look up the cause of the mortality of the black abalone, you find Withering syndrome, a bacterial infection that causes the foot of the abalone to shrink, thus making it unable to cling to a rock. For this reason, the black abalone is globally listed as critically endangered. So was it just coincidental that they disappeared from Cedros during El Niño?

As with many diagnoses, the answer is more complex than one cause. Black abalone can live in harmony with this bacteria—it doesn’t affect them. However, as soon as the water warms up even a little bit, they are overcome by this bacteria. Therefore, the abalone at Cedros may have been living with the bacteria, but a rise in ocean water temperature—less than four degrees Farenheit—brought about their collapse. Like a murder mystery, the bacteria is the smoking gun, but it was El Niño that pulled the trigger—and Eduardo lives in the neighborhood and can testify as a witness.

People like Eduardo, who live closely tied to natural cycles, can tell us a lot about big picture changes. Although the black abalone is a small creature now nearly extinct, it disappeared rapidly, taking with it part of the industry of the cooperative of fishers (and divers, since they must dive to harvest abalone.) On Cedros, they already had a high-functioning cooperative that could respond to this change and continue to support its members. He adapted deftly to a similar change in water conditions this year with more time spent trapping lobster, which thrive as the big fish suffer (warmer water is less nutrient-rich, so the little fish are fewer, which means the big fish are fewer.) It would seem that the key to adaptation in this community is diversification. Diversification means fishing for different fish and crustaceans, but also the market flexibility built into one of Eduardo’s supporting institutions, the cooperative.

Dr. Heather Leslie, a marine conservation scientist and professor at Brown University, agrees. Over the last ten years, she and her graduate students have studied the varying impacts on small-scale fisher communities in Baja California Sur, the southern half of the peninsula. Leslie recently used the guiding principles of economist Elinor Ostrom to determine the states of both social and ecological systems in these communities. “I originally started this research because I wanted to gather all of the data about this region into one place,” she tells me. “The Ostrom framework just helped us figure out how to compare the communities.” The approach is called SES, social-ecological systems, and it had never been deconstructed and applied to a specific group of communities before.

Leslie and her coauthors looked at four key systems: she wanted to know who fishes, where they fish, what they fish for, and how they deal with each other. Finally, she wanted to understand how these four factors are linked. She calls this “operationalizing” SES. They managed to combine both data about fish and data about people to try to grasp how vulnerable each of these systems are to an impact—an impact such as El Niño or a powerful hurricane season. They expected to find that groups with one strong system would be strong in the other three. But they found just the opposite. These ecological and social factors weren’t correlated at all. While some communities had strong institutional support, such as the coop on Cedros, they might then be challenged by a system that naturally holds few species. So even though their hypothesis about correlation was wrong, they found something even better. They found that you can’t look at only one ingredient of the system and expect to know how the cake will bake.

For example, in Magdalena Bay south of Cedros, there are many different species of fish. This natural abundance would lead an ecologist to call that system stable and resilient to shock. However, Magdalena Bay scored low in their ‘human actors’ category: there are too many fishers, and they remain isolated from each other and their market. A social scientist would declare the system weak and vulnerable to shock. It is only by looking at the two together that we get a dynamic picture of Magdalena Bay. The approach begins to illuminate how to prepare the area for a shock like El Niño.

Turns out Magdalena Bay and the rest of Baja are feeling that shock right now, whether by changes in fisheries or potentially devastating weather. Climate scientists at NASA compare this year’s El Niño with 1997, calling it a “Godzilla” El Niño. All this hot water means not only a change in the ocean, but a change for the land—they predict a hurricane season of epic proportions for the Pacific. Five hurricanes have already formed south of Baja this year, unnervingly early in the June-through-November hurricane season. The second storm, Blanca, was the earliest recorded hurricane to ever hit the Baja peninsula.

All of these changes impact not only the small abalone or the individual fishers like Eduardo, but the largest mammals ever to live on earth: whales. In warmer, nutrient-poor water, whales, like the one we saw breaching in the Pacific, struggle to find enough food. Whether or not we see them, the whales still exist under the surface, adapting or suffering with change.

Much of the time, changes in climate are hidden from everyday view and our lives continue without a breach. But once in a while, these changes explode to the surface to disrupt our view, crashing down with an enormous splash. Indications of these changes are lived and breathed by Eduardo, his family, and others who live tied to the coast. We can listen to their observations and take heed of their accounts of the sudden or long-term change. We can learn how to adapt nimbly and with care for our resources. But we must always be on deck to scan the horizon for these events. Eduardo is standing watch at the helm—we just have to listen.