FUGONG, China — “We no look at secrets,” said the woman in camouflage, switching to broken English perhaps to reassure me. Her senior officer—a man in a crisp navy uniform and flak-jacket that read “Public Security and Border Defense”—told me again in Chinese, “We just scan for certain information. We won’t invade your privacy.” His tone was cordial but his face serious. A box with a jumble of wires lay on the desk between them; one of them would fit my iPhone.

I’d been through a lot of security checkpoints but never encountered a situation like this. “It makes me really uncomfortable,” I told the officers. Yunnan province in China’s southwest corner shares 2,500 miles of porous border with Myanmar, Laos and Vietnam, the former two Golden Triangle countries notorious for drug production. Security checkpoints like this one are commonplace in the region.

When I arrived by bus, everything about the checkpoint had seemed routine: scanning all passengers’ identification cards into the system, asking me to get off the bus to register my passport, even rifling through my personal items. (Deodorant always puzzles officials.)

But when they told me they were still verifying my identity with the higher-ups and sending the bus on without me—that was different. The bus transfer station was still 30 minutes away and my final destination—where a friend was waiting—lay another six hours further. I was miffed.

The Nu River flows through northwest Yunnan. Myanmar is just beyond the far mountain range

Senior officer Wang gave a nod to the woman. “We are filming this for everyone’s protection,” he said. On cue, she pointed a GoPro-like device at me and clicked. Wang continued: “So are you refusing to let us see your phone?”

I felt the tension ratchet up. My inner American was triggered, screaming to demand my rights, although I well know that in China I don’t even have the right to remain silent. I told my inner American to shut up.

“No, I’m not refusing,” I said, trying to remain diplomatic, especially with the camera rolling. “‘Refusing’ is a very strong term,” I continued. “But I am very uncomfortable with you plugging in my phone and downloading—or uploading—whatever you want. I have private information on here: passwords, bank account info, things I’m not comfortable you accessing. And frankly I don’t know my legal rights or obligations in this situation.”

“We of course act in accordance with Chinese law,” Wang reassured me firmly. “We are just a bit unsure of your reason for traveling.”

I was on my way to see a Lisu friend in Fugong county in Yunnan’s northwest corner. The Lisu are one of China’s 56 officially recognized ethnic groups and predominantly Christian thanks to the British missionary J.O. Fraser, who moved to Yunnan in 1910. A hundred years later, Fugong county has the highest percentage population of Christians in all China (about 80 percent). If I couldn’t be home for the holidays in the mountains of Idaho, Christmas with the Lisu seemed like the next best thing.

But religion and foreign influence are sensitive issues in China these days. President Xi Jinping began emphasizing the need to Sinicize China’s five official religions—Islam, Catholicism, Protestantism, Buddhism and Daoism—in 2015, part of a campaign to align religion with socialism and guard against so-called foreign ideas and influence. Formal five-year plans to Sinicize Protestantism, Catholicism and Islam have already been passed. China also released new regulations in 2017 on religious education, the types of religious organizations allowed to exist, where they may be located and the activities they organize. After a “soft opening,” those regulations are now slowly coming into effect.

Seven Lisu villages gather for a Christmas celebration in Tuozizuo. The Lisu have long enjoyed music, which missionaries encouraged by translating hymns into the local language

Last year in Beijing and Chengdu—capital of Sichuan province—the authorities closed two of the best-known Protestant house churches in all of China. One town even banned Christmas. Muslim house mosques have also been raided and shut down for operating without local approval; some have been threatened with demolition. And in Xinjiang, where as many as a million Uighur Muslims languish in “re-education camps,” Uighurs at checkpoints like this one are forced to upload apps that monitor their phones. Other groups, such as the Lisu Christians, have a much better working relationship with Party officials.

“Officer Wang, I know your job is to keep China’s people safe and protect the borders,” I said. “I support that. But is there any alternative to plugging in my phone? Perhaps looking through my photos?” I suggested. “Another officer did that once.”

Officer Wang turned his back to speak quietly into the radio on his shoulder. After a moment, he turned back around. “I spoke with my supervisor and we will start with looking through your phone.” We both breathed a little easier.

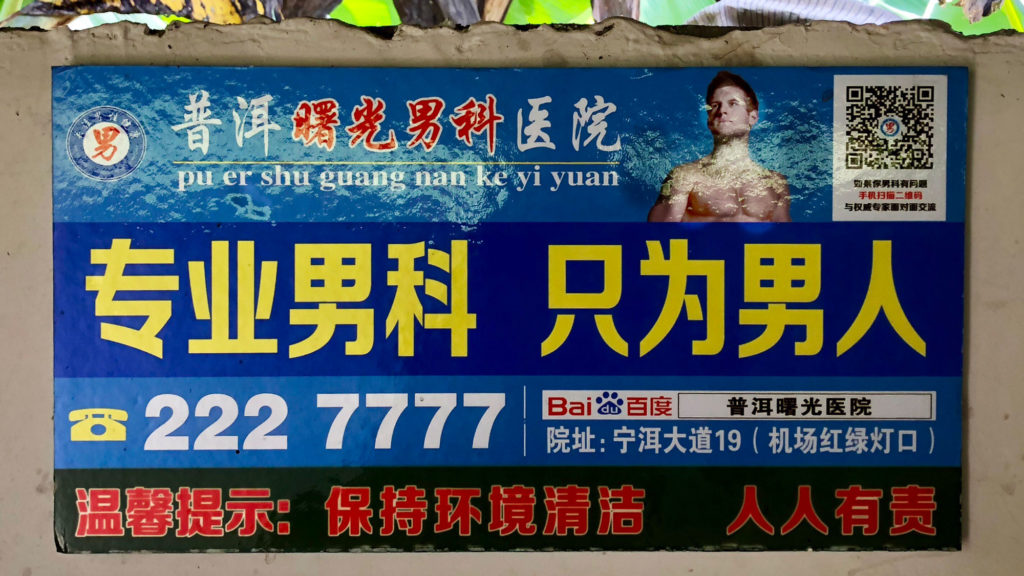

The English-speaking officer took my phone and scanned though my file names, even opening an ICWA newsletter. (She quickly closed it with no comment—perhaps not my best work?) Then she scanned through my photos, opening any with Chinese writing: a money transfer, a receipt for my kitchen propane tank, an ad for a male hospital featuring a shirtless foreigner. “He looks like my friend, heh heh,” I said sheepishly. If you ever want to feel self-conscious, show all your photos to a stranger with a gun.

The officer especially enjoyed the photos of my parents’ visit to Yunnan. “That’s great!” she said about my mom on an elephant. I zoomed in on her shocked face for full effect. The officer laughed. Now it felt like going through travel photos with an old friend. She seemed genuinely curious about how foreigners experience China—until Officer Wang nudged her to remind her this was work, not play. “Ok, that’s enough,” she said handing me back the phone with a smile. I smiled back and said in English, “No secrets.” Minutes later, they arranged a ride for me in a passing car and my journey to Fugong continued.

“Professional andrology, only for men.” He really does look like my friend

“Professional andrology, only for men.” He really does look like my friend

Xishuangbanna, southern Yunnan: My mother’s first elephant ride

Xishuangbanna, southern Yunnan: My mother’s first elephant ride

Yunnan is often characterized by the Chinese expression “The mountains are high and the emperor is far away.” It is in the opposite corner of the country from Beijing, after all. But I was struck on my Christmas sojourn by the extent of the Party’s involvement in everyday life and, more striking, the normalcy of it. Perhaps being stopped at the security checkpoint made me hyperaware, but every step of my journey—from roads to Christmas sermons—seemed to be covered in red fingerprints. The emperor may be far away, but he has an impressive reach.

“The government is building this road,” Mr. Wang told me. Wang is a road construction project manager and the law-abiding citizen the security officers asked to take me to the bus station. The road is a mess of dirt and rocks. The rubble and frequent stops for construction crews make the 100 miles to Fugong a six-hour journey. It’s possibly the worst road I’ve ever encountered. But the government is widening and resurfacing it and the route is expected to serve as a new lifeline for people previously left to subsistence farming. “Crops would go bad before farmers could get them to market or transportation costs would just be too expensive,” he explained. “This road will change everything.”

What the road lacks in comfort it makes up for in natural beauty. It winds along the Nu (or Angry) River, one of the world’s longest free-flowing rivers. Beginning in the glaciers of the Tibetan plateau, its swift, slate-colored waters cut a deep canyon through northern Yunnan, with steep mountains rising from its banks, like slumbering dragons guarding against intrusion from the outside. Just over the west range is Myanmar.

For thousands of years, the region has been accessible only by boat, and even then only to those willing to brave angry waters. But with the road comes progress. We passed small hydropower stations releasing mountain runoff into the river. Neat little rows of identical houses lined the riverbanks, part of the government’s campaign to relocate remote residents and eliminate all poverty by 2020. Red banners announced in large white characters the new provision for 12-year compulsory education. Change is afoot.

The mountains are high

It was dusk by the time I arrived in Fugong and met my friend, Ci Mikuan (pronounced Tss Me Kwon). He greeted me with a handshake, his big hand filling my grip, and a typical Lisu greeting: “Hwa hwa!” Peace! Mikuan is a short, stocky man with a round face and grown-out buzz cut. I climbed on the back of his motorcycle and we rode for another 40 minutes up into the mountains, switchbacking on a narrow road until we hit wet concrete. “The government is building this road for our village,” he told me, his voice animated. We parked his motorcycle and walked another 20 minutes on a dirt path. “They built housing in town for us, too,” he added, “just down the mountain,” referring to one of the relocation villages I noticed on the drive in. “But no one wants to move, especially now that we’re getting a road!” he said. I wondered how the wires got crossed on that policy implementation.

Finally we arrived at Mikuan’s home. The kitchen, a small wooden structure, glowed from a fire inside. Two small cinder-block structures surrounded a concrete patio overlooking the valley we just traversed. Light poles stretched up the otherwise dark mountainside like a ski lift at night, another government project after the village got electricity just 10 years ago.

Mikuan’s mother and wife emerged from the kitchen and both shook my hand firmly. “Hwa hwa,” they said. “Hwa hwa,” I replied, returning their peace. They invited me into the kitchen, where logs burned inside a five-foot square fire pit sunk almost a foot into the floorboards, with a blackened kettle on top. We sat on the edge to warm our feet. (The December air is chilly at 5,700 feet.) Mikuan’s wife busied herself charring a pig leg over the fire while three rats hung above our heads to cure in the smoke. I wondered which would be on the menu the next day.

Rats hang above the fire pit to smoke cure

Mikuan’s mom is a stout woman with sagging jowls and hair wrapped in a bright pink headcloth. “Do you speak Lisu?” she asked me. She is friendly and outgoing but speaks only Lisu, part of a completely different language family than Mandarin. I pointed to my ear and shook my head in response, unknowingly answering her question. “Lisu is easy to learn because we have a written language,” Mikuan translated for me. The writing system was developed by Fraser, the British missionary, and proved critical to the success of his work. He made use of capital letters from the Romanized alphabet, turning many upside-down and adding punctuation marks for tones. The result looks more like the product of a cat walking across a keyboard than a sentence. “NU Ll SU M ⊥l RO HW NY Ll SU ⊥O 7 S7 L ΛO=,” Mikuan’s mom informed me. “The best way to learn Lisu is to find a Lisu wife.” Mikuan is 34 with four kids already, and it baffles him that I’m 36 and single. “You should find one soon,” Mikuan told me. I nodded in agreement. “Maybe a Lisu language teacher,” I joked, fighting back a yawn.

It had been a long road to Fugong and I realized I was exhausted. “You should rest early,” Mikuan said as his wife scraped the blackened shank with a cleaver until white skin shined through. He led me into one of the cinder-block buildings with two small couches, a bed piled with blankets and a coffee table. The white plaster walls were covered with a toddler’s crayon writing and taped-up photographs: a family photo in Lisu ethnic dress; Mikuan’s married sister who lives in Myanmar; another sister with five children and her late husband; and a group photo of 150 people at a church training. Overlooking them all was a framed Magic Motion Jesus picture with a halo of light around his head and clear eyes that appear to glisten when viewed from different angles.

“Thank you, Mikuan.” I said after him. “Goodnight!” The warped metal door scraped against the concrete as I tried to shut it. I drew the curtains over the glassless window frame and switched off the light, groping in the dark for the bedframe. The mattress was a plywood board with a blanket draped over it. I quickly stripped down to my long johns and wool socks and crawled into bed. Shivering, I left on my beanie and drew the other two blankets tightly around my neck, quickly falling asleep under the watchful eyes of Magic Motion Jesus.

A view of the Nu River valley from Ci Mikuan’s kitchen patio

A view of the Nu River valley from Ci Mikuan’s kitchen patio

Mikuan borrowed a keyboard one afternoon so I could play and we could sing some hymns with his family

Mikuan borrowed a keyboard one afternoon so I could play and we could sing some hymns with his family

At breakfast I was relieved to see pork and turnip soup on the table along with leftover chicken. We sat on the patio at a knee-high table and watched the thick clouds flow through the Nu River valley half a mile below. As we ate, the clouds gradually climbed up the mountainsides and dissipated into the blue skies.

“What do you keep busy with here?” I asked Mikuan.

“There’s not much to do,” he confessed. “We grow our own food and raise a couple pigs each year. It’s enough. We don’t have much land and what we do have doesn’t grow much. Sometimes we grow a little bit of corn, but this year I didn’t even plant that because the government paid us to not grow corn.” (China’s invisible hand has been actively trying to reduce its stockpile of corn.)

“The government gives us about $125 each month and covers our kids’ school fees,” he continued. “A couple years ago they also paid for the material to build these bedrooms and patio so we could tear down the old wooden building. It’s expensive to get materials up here, especially back then before the road.”

Mikuan, the consummate host, picked out an unidentifiable organ from the chicken and placed it in my empty bowl. A small bubble of skin curly cued into a thin tube, like a cartoon organ from the board game Operation. It was bitter and grated like grains of sand between my teeth. But I smiled, grateful it wasn’t rat spleen.

Ci Mikuan’s home church is perched at the top of the mountain range in Nananjian village

“How’s the government’s relationship with the Church here?” I continued.

“Sometimes they visit our services to make announcements, but generally the government doesn’t bother us,” he said, “as long as there’s no conflict within the Church.” There are six villages in their area, each with a church of hundreds to thousands of parishioners. “When we vote for Church leaders, someone might get upset if they don’t win but our Church leaders deal with that.”

Aside from in the Church, however, village leaders are rarely Christian, despite the overwhelming majority that professes faith. The Party secretary is the highest-level of local leadership and must be a Party member, obviously. So villagers figure it’s easiest to get things done with the Party secretary if the village mayor and vice-mayor are Party members as well. And Party members must be atheists.

Despite the strictly atheist Party leadership, China’s constitution promises “freedom of religious belief.”

“We have to follow the law in order for the Party to protect our faith,” Mikuan told me. “For example, the Party says no outsiders can come teach us because they change the stories and teach us wrong things.” His statement echoed one of President Xi’s in 2016: “We must resolutely guard against overseas infiltration via religious means and prevent ideological infringement by extremists.”

As he spoke, I was struck by the clear social contract between Party and Church: The Church will uphold Party leadership and help maintain social stability while the Party allows the Church to function, and will bring increasing prosperity to its people. Far from a separation of church and state, the two have a symbiotic relationship in China for better or worse. I witnessed that most clearly at the Christmas Eve service, a celebration of church and state.

Christmas dinner with a thousand others in Tuozizuo, Nujiang Lisu Automonous Prefecture

A celebration of church and state

On Christmas Eve in the afternoon, we switchbacked down the mountain. Each year, the six surrounding villages gather in the town of Tuozizuo for a four-day cyclical celebration: church, basketball, food, repeat. The host church is a large yellow building surrounded by red square pillars and topped with a red tile roof and flying eaves. A white cross stands atop it all, front and center. Out front, a large concrete patio serves as a banquet hall and a basketball court. Rugged mountains rise in every direction and the Angry River flows by courtside—a spectacular setting for basketball.

Which was good because the basketball was not spectacular.

The annual basketball tournament is central to Tuozizuo’s Christmas celebration. Each village sends a team outfitted in an eclectic mix of uniforms. This year, various athletic jerseys made an appearance:

#23 from the Nananjian Bulls,

#11 from the Benjiake Rockets,

#3 from Baoding Shoe Enterprise,

and another #11, but from “As long as you love me.”

One player forewent the jersey and wore an inspirational t-shirt instead:

WINNERS

QUIT

NEYER

WIN

A Lisu man sips tea courtside at the Christmas basketball tournament

Men lined the concrete steps around the court sipping tea from small bowls and cheering indiscriminately for every basket. They also laughed outright at every missed lay-up and airball, which was often. So it provided for some of the most upbeat and cheerful basketball I’ve had the pleasure of watching. And I was sure to just watch.

Eyes lit up when I arrived. “Un-Bee-Aee!” they yelled at me with wide grins, pointing to their NBA jerseys. In China, people are often skeptical I’m really American. Most think I’m French or Italian because all Americans—at least the ones on TV—are tall and muscular. If they were disappointed by my height, they would have been even more dismayed by my shooting skills. So for honor and country, I stayed safely on the sidelines with the other men sipping tea and laughing at the incompetence of others.

When the food was ready, a flurry of women transformed the court into a banquet hall with fold-up tables, disposable bowls and single-use chopsticks. A plastic washbasin full of beef broth soup and leafy greens occupied the center of each table and 25-gallon bins of rice were scattered around the court. But the community meal was just an intermission between basketball and church. Once everyone had broken his or her chopsticks in half to use the splinters as toothpicks, it was time for the Christmas Eve service.

Breakfast on Christmas morning

An aisle runs down the center of the church separating the heads of short black hair from those covered in bright pink, sky blue, clover green and deep purple headscarves—flowered, striped and checkered. “Hwa hwa!” “Hwa hwa!” more than 800 congregants greeted one another.

A group of 30 men shuffled up on stage, timid like junior high boys forced to perform by their mothers. Soon they were joined by 30 women in skirts of pink or black velvet and vests to match, adorned with large white buttons and silver studs. They all pulled worn hymnals out of woven satchels and the women covered their faces in embarrassment until the choir director gave them their pitch.

Suddenly “Joy to the World” in the Lisu language rang out in full four-part harmony. Do-ti-la-so, fa-mi-re-do! The small building reverberated as the nasal-sounding sopranos descended the scale and rose again: Let earth—receive—her king! The drone of the basses echoed underneath: Heav’n and nature sing, and heav’n and nature sing. Besides developing the Lisu script, Fraser also translated portions of the New Testament and hundreds of hymns into the local dialect. The Lisu have been singing these same four-part harmonies for 100 years.

Listen: Joy to the World (Lisu)

Soon “Joy to the World” became “Silent Night.” I had not been expecting Christmas carols and, as I sat on the hard pew—a foreign observer taking notes on outfits and interior decoration—I closed my eyes and reveled in the comfort of the shrill yet familiar tune. I pictured my family around the tree in Idaho. I thought of the snow gently falling and the warm glow of our cabin under the stars. I said a prayer of gratitude for the hope, peace and joy found in this season. And as the choir sang, in the distant mountains of Fugong, with no tree or Santa Claus, Christmas came in my heart.

Over an hour and four choirs later, my Christmas spirit was waning. The highbrow sermon that followed—brought by a very short, very serious man in a black robe—only fueled my inner Scrooge. Some took notes while others played on their phones. Babies cried in the overflow while kids lit off firecrackers on the basketball court. It was a tough crowd. After 45 minutes and well over two hours into the service, he concluded his sermon with little fanfare and stepped down from his stool behind the pulpit.

Then a tall man in an olive drab trench coat stepped up to the pulpit. His face was stern and light shone off his scalp through thinning hair. But as soon as he spoke, people paid rapt attention. They listened and laughed, and leaned into what he was saying, as though it were relevant to their lives. And it was, because Mr. Hu was a Communist Party official from the prefectural government. He spoke in the local dialect, so while everyone else listened attentively, my thoughts and eyes began to wander.

I examined the decorations on the stage behind him: a cross-stitch of Jesus with his disciples at the Last Supper, a mural of a menorah flanked by a black Bible and a blue hymnal, a poster that read:

LOVE YOUR COUNTRY, LOVE YOUR FAITH

BE LIGHT, BE SALT

I usually heard both those sentences the other way around.

A man writes a new song in Lisu in preparation for choir practice

Another poster on the front wall read in Chinese and Lisu:

PATRIOTIC PLEDGE

1. ARDENTLY LOVE THE SOCIALIST MOTHERLAND, UPHOLD THE LEADERSHIP OF THE CHINESE COMMUNIST PARTY.

2. UNIFY THE BROADER FAITH COMMUNITY, RESPECT PERSONAL FAITH AND FREEDOM OF RELIGION.

3. OBEY DISCIPLINE AND ABIDE BY THE LAW, MAINTAIN PUBLIC MORALITY, RESPECT THE OLD AND CHERISH THE YOUNG, AND WILLINGLY HELP OTHERS.

4. ADVOCATE SCIENCE, DO AWAY WITH SUPERSTITION, GUARD AGAINST OUTSIDE INFILTRATION, BE AWARE OF AND RESIST HERETICAL BELIEFS.

5. DEFEND THE UNITY OF THE MOTHERLAND, ETHNIC UNITY, AND RELIGIOUS AND SOCIAL HARMONY, AND CONTRIBUTE TO THE BUILDING OF MATERIAL, POLITICAL AND SPIRITUAL PROGRESS.

A tap on my shoulder called me out of my headspace. A man in the next pew over who wanted a photo of me had sent a chain of taps to get my attention. I subtly smiled for the camera, not wanting to distract from the service.

*FLASH*

His phone illuminated the entire sea of headscarves behind me and I wished I had a hymnal to hide behind. Meanwhile Official Hu concluded his hour-long sermon with a deep bow, followed by three more choirs and three more identical renditions of “Joy to the World.”

Well after 10 p.m., the crowd was finally dismissed and shuffled out the back into the darkness. I shook more hands—“Hwa, hwa”—and smiled for more photos—*FLASH, FLASH*—then followed Mikuan out through the crowd.

“So what did the official say?” I asked.

“To please move down from the mountains into the government’s relocation housing.”

“He took an hour to say that?” I asked incredulously.

“He also said, ‘Sorry about the corn thing,’” Mikuan said paraphrasing the official. “‘That was our mistake and you can grow corn this year.’”

I thought about that for a moment, surprised to hear an official’s confession.

“So will you move your family?” I finally asked.

“Nah, I don’t think so.”

Men post selfies of us on social media during the Christmas Eve service

Men post selfies of us on social media during the Christmas Eve service

A resettlement village on the banks of the Nu River. The characters read:

A resettlement village on the banks of the Nu River. The characters read:

“China Hydropower Bureau 14 Targeted Poverty Alleviation Build Up Poverty Alleviation”

The long road out

On the third day of Christmas, I left Fugong. The cycle of celebration—church, basketball and food—would continue another two days, but a friend’s daughter was getting married in northern Yunnan so I had another celebration to get to.

Mikuan walked me to the main road where I could hitchhike back toward civilization. I stood on the corner waving down cars as people walked by on their way to the 8 a.m. service. “Hwa hwa!” each one greeted me, extending a firm handshake and entreating me to stay for just one more day. Finally, a minivan stopped, saving me from the abundant hospitality, and I joined two poverty-elimination workers for the long ride out.

Not far down the road we passed a red banner with large white characters:

EDUCATION IMPROVES THE COMPREHENSIVE QUALITY OF THE PEOPLE

“Education is the key,” one of the workers told me. “It’s the only way to change people’s lives here. The government is in the process of making education compulsory through 12th grade, not just 9th grade. And any kid from a poor family can basically get through college free. But it depends so much on the parents,” he said matter-of-factly. “There are two kinds: the first have already eaten a lifetime of bitterness and are done with that way of life. The second are content to just fill their bellies.”

I thought of Mikuan and wondered which kind of parent he is.

The young man continued: “We will make mistakes on this campaign, but we are learning as we go—‘crossing the river by feeling the stones,’” he said, invoking the words of China’s paramount reformer, Deng Xiaoping.

He paused for a moment as we bounced along the rough road. The Angry River rushed by.

“Does your government do poverty alleviation work?” he asked me.

“There are government programs to help,” I replied, “but I haven’t seen a campaign like this one. We depend a lot on non-profits and churches to fill that role.”

“Whether government or churches,” he said, “anyway, it’s all for the good of the common people.”

I nodded silently, needing some time to think about his statement. Conveniently, it’s a long road out of Fugong.

Ci Mikuan with his wife and two youngest children

Ci Mikuan with his wife and two youngest children

More audio:

I surrender all (Lisu)

Hymn (Lisu)

He Came to Save Us (Deck the Halls, Lisu)

Construction on the road out from Fugong