‘It is the end of a family—when they begin to sell the land,’ he said brokenly. ‘Out of the land we came and into it we must go—and if you will hold your land you can live—no one can rob you of land.’

—Wang Lung, The Good Earth by Pearl Buck

CIZHONG, China — Da-ke-te came out swinging. His dark pecks bulged as he touched gloves with his opponent, Di-da-er, a six-packed but lanky Chinese-Kazakh. Forty-one seconds later, the cage match was over and Da-ke-te was draped in an American flag. “I really like the people and culture here,” Dakota Hope said in his victory interview. “Hopefully next time, I can see the Great Wall of China.”

I rarely watch cage fighting, and even less so on the Tibetan Plateau. But I had just arrived in Cizhong village, a full day’s drive from the already remote Shangri-la in northern Yunnan province, and my elderly hosts were showing me the error of my ways. They had skipped Wednesday mass and sat on their wicker sofa watching match after match on television. Xie Heyu’s head is shaved and although it was nighttime, he wore bug-eyed women’s sunglasses. His wife Yi Xi wore a black puffy vest over a traditional Tibetan skirt with stripes of blue, green and pink hanging to her shins. A blue Mao cap sat cockeyed on her head.

“Are you French?” she asked me, a question I’d be asked many times in the coming days. “No,” I replied, taking pride in Da-ke-te’s dominant win. I pointed out that he and I are both American, the same height and pretty much the same build. My joke fell flat.

Yi Xi and her husband watched a thick Chinese young woman destroy a tall skinny Russian in the next match while I studied the wall behind the television. Front and center hung a laminated poster of China’s leaders since the Communist revolution—Mao, Deng, Jiang, Hu and Xi—flanked by individual portraits of Chairman Mao and Chairman Xi. These were bookended by a framed poster of Jesus and Mother Mary and a cross-shaped cross-stitch of a dove descending on Jesus with the English words “HOLY SPIRIT” at the bottom.

The region is known for its ethnic and religious diversity, including Tibetans, Naxi, Lisu, Hui and Han and practicing Buddhists, Catholics, Protestants and Muslims. “In [Deqin county], all ethnic groups are united and religions are in peace and harmony,” Xiao Wu, the head of the local Ethnic and Religious Affairs Committee, recently told Xinhua News.

But Cizhong wasn’t always so inclusive. French missionaries first built a Catholic church in the region in 1867—hence the questions about my provenance—but their work was met with resistance from local Tibetan Buddhists. As antagonism toward foreign influence grew across China and the Qing dynasty gradually crumbled, the Buddhists finally took action in 1905 as part of a larger “exorcise foreign religions” movement. They killed the missionaries and torched the church to ashes, along with nine others in the region. The church was rebuilt at its present location in 1914 and Catholic mass resumed until missionaries were expelled in 1951 after the Communist revolution.

“When the French missionaries came, they brought their own grapes and wine-making techniques in order to serve Holy Communion,” a tour guide, Liu Jianhua, told his entourage of Chinese tourists. I was tagging along as they strolled through the church grounds. Palm trees skirt the arched entrance of the church whose stone bell tower and flying eaves rise above the village. Adjacent to the grassy courtyard stand the former living quarters and a vineyard that still grows the cultivar brought over in the 1800s. Rose honey grapes were thought to be extinct after a blight wiped them out in France, Liu told us. But in the 1990s, a French sommelier rediscovered the world’s last acre of rose honey grapes on the grounds of the Cizhong Catholic church. A sign outside the vineyard reads:

The ross honey grape is original in france but after 1860 grape disaster,this kind grape in france was extinct,sofor now,this place,is the only place in the planet have this kind grape.

Attracted by Cizhong’s historic church and kind grapes, in the late 1990s French backpackers and intrepid Chinese tourists began journeying to the outer reaches of Shangri-la where Tibetan Catholics and Buddhists live in perfect harmony and maintain French-style vineyards on the banks of the Mekong River. To me, idyllic Cizhong sounded like a good place to spend Easter.

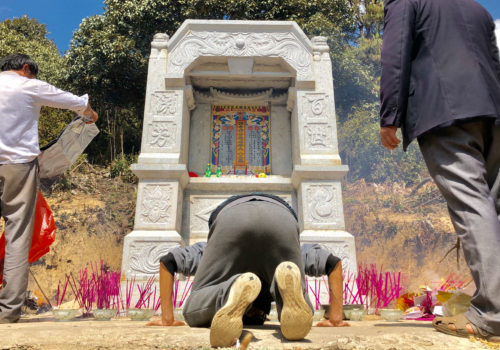

“Jesus came as a light into the darkness,” Father Yao told me at the Saturday evening candlelight mass. He is a Han Chinese from Inner Mongolia who has led Tibetan parishioners in Catholic mass since 2008. His congregants flocked around him on the stone steps of the church as he lit a large white candle, struggling against the wind and having to re-light it several times. Yao passed the flame to those around him, each clutching a small candle, and they, in turn, passed it to their neighbors until a hundred flames flickered in the darkness. Their faces glowed as they made their way up the steps into the church where they affixed their candles to the top of the pews with drips of hot wax. A 25-gallon jug of holy water sat in the aisle, ready to baptize any wayward flames.

The chanting started as parishioners found their seats in the pews.

Voices—some deep, some shrill—droned over a minor scale, reverent yet haunting. The French priests had learned Tibetan—although the wrong dialect, they later discovered—and worked to localize doctrine: Catholic liturgy with Tibetan characteristics. Though a book of liturgy exists—a seven-year labor of love by one parishioner—no one needs it anymore; each member knows the chants by heart. Above the droning voices and throughout the rest of the service, phones rang, kids played tag and battery-depleted smoke alarms beeped incessantly in surround sound. Only one man set his coat on fire. After administering the Eucharist, Father Yao pronounced a beautiful blessing over watermelon, ears of corn and yogurt that parishioners had placed at the altar.

But all was not well in Cizhong. “Our land is gone,” Yi Xi had told me between rounds of cage fighting. “This used to be a beautiful village, now we have nothing.” Infrastructure development is sweeping the region, transforming lives and landscapes in its wake—and not always for the better. However, my disappointment in Cizhong far exceeded expectations. Thanks to a new dam downriver and displaced villages relocating to Cizhong, its rural idyll has been destroyed and with it, residents’ means of providing for themselves.

They paved paddied rice and put up a parking lot

Cizhong stands on the banks of the Mekong River, what Southeast Asia expert Brian Eyler calls “a dam builder’s dreamscape.” In his new book, Last Days of the Mighty Mekong, he writes: “The province’s terrain drops 2,000 meters from its mountainous northern border with Tibet and Sichuan to tropical Xishuangbanna in its south… For the Mekong or any of Yunnan’s numerous rivers, almost any location where the valley narrows makes an ideal setting for a high walled dam.” But while hydropower is a clean and relatively inexpensive solution to China’s voracious energy needs and pollution challenges, it is a contentious issue here and across Southeast Asia. It displaces communities, threatens the ecology and strains international relations over shared natural resources.

About ten miles downriver from Cizhong is the Wunonglong Dam, completed just last year and one of over 20 dams already operational or in the pipeline on the China side of the Mekong. It sells its electricity to power-hungry Shenzhen, home of the tech giants Huawei and Tencent. Although the dam raised the water level over 60 meters and flooded numerous villages upriver, it isn’t the flooding itself that is destroying Cizhong. The village still stands safely on the riverbanks as it has for hundreds of years, just beyond the water’s reach. However, it is not beyond the reach of the state.

All those flooded villages needed somewhere to move and flat land in the Mekong’s narrow gorge is scarce. But not in Cizhong. The small village is situated on a long narrow plain on the bank of the Mekong surrounded by rice paddies four or five times its size—at least until the relocations began. Now, Cizhong’s entire plain of fertile farmland has been paved over and converted into residential plots and roads (2015-2019 time lapse here). Though villagers were compensated, compensation schemes do not take into account both the value of the land and loss of future income. Residents’ rice fields and vineyards are now gone forever and along with them their means of production. They can no longer grow rice to eat or wine to sell and, perhaps worst of all, tourism dollars have disappeared.

“No one stays in Cizhong anymore,” Ciren Quzong told me over a morning pot of yak butter tea. “They just take photos of the Catholic church and leave.” A Tibetan Buddhist, Ciren and her Naxi husband own one of the only traditional wood structures remaining in the village that they’ve turned into a guesthouse and small café. I was the only customer, slowly sipping the creamy salted drink as I browsed thangka paintings, a poster of Potala Palace in Tibet and photographs of the Panchen Lama. Among them, the poster of Mao, Deng, Jiang, Hu and Xi seemed out of place.

“How do you say rou in English?” Ciren asked me.

“Meat,” I replied.

“Meat pianyi,” she said.

“The meat is cheap,” I instructed.

“The meat is sheep,” she repeated.

“Cheap!” I corrected. “Ch-ch-ch-cheap meat!”

“Sheep meat, sheep meat, sheep meat!”

Soon she had me scrawling vocabulary in her notebook:

tomato

potato

Let’s eat!

Do you like spicy?

Would you like to eat and stay in my home?

We were making good progress with Ciren recording my pronunciation on her phone when we were interrupted by rumbling engines. A group of Europeans rolled into the village plaza and dismounted their motorcycles. They peeked into the church, strolled through the vineyard and rumbled off again. They didn’t even take some wine for the road—only photos. Visitor numbers may be up thanks to the new highway, but tourist dollars are down. Cizhong is now just a stopping point on the way to somewhere else; it has lost its je ne sais quoi. “I have no idea what we’ll do,” Ciren laments.

Tibetan guesthouse owner Ciren Quzong stands in her café ready to practice her English with guests

Wu Hongxing shares Ciren’s fears. He runs a tour and trekking business based in Cizhong and sells wine from a shop right next to the church. A poster on the wall advertises his different tours and I commented on a photo of him hugging his pack mule. “Last year I sold Ranmu because numbers are so low,” Hongxing responded. Before the relocation project, he used to run about 20 treks per year but now he’s down to less than half that. He saw me cringe. “It’s ok,” he reassured me, “I can buy a new Ranmu someday.”

We chatted as Hongxing gave me a tasting of his family’s rose honey wine. His father, Wu Gongdi, was the first in Cizhong to begin producing wine again in the 1990s. He started with vine cuttings from the church vineyard and learned from his aunt, a nun who had served with the foreign missionaries. Hongxing poured me two glass mugs of wine from small oak barrels and said, “These are both from October 2017.” He sniffed and sipped from each glass before handing them to me with my undiscerning palate. “It’s not not wine,” I thought as I sipped the first, recalling the tasting notes of a wine aficionado in DC to whom I had presented a bottle of Yunnan Red. The second pour was from late harvest grapes, left longer on the vine to dehydrate and concentrate sugars. I detected notes of grape Jolly Rancher and Dimetapp; it was full-bodied with a syrupy finish. I liked it.

Only two vineyards in Cizhong—his and the one on the church grounds—still grow the original rose honey cultivar, Hongxing told me. The other vineyards all grow a Cabernet varietal that the government introduced with visions of monoculture prosperity and that farmers would sell to the Shangri-la Wine Company. But now with farmland turned into family housing, those vineyards are gone. Only a handful of families still own land up in the mountains and they mostly grow corn.

Hongxing is worried about the survival of honey rose and his vineyard in the long term. The water’s level has risen to just below the village and now moves so slowly I couldn’t tell which direction was upriver. That will affect the moisture level and temperature, Hongxing said, which will alter the air, soil and character of the grapes he grows. The changes are gradual and he expects them to hit in full in about three years.

He looked at me completely at a loss. Our land is ruined, our crops are ruined, even our scenery is ruined, he said. Besides the church, there’s nothing left for tourists to enjoy. What more do we have?

Reliance means compliance

But not everyone is so pessimistic. “Parlez-vous français?” Xiao Jieyi asked me after Good Friday mass. There was a warmth in his voice and his grey eyes sparkled. “Non,” I replied with as much Gallic intonation and irony as I could muster. We switched to Chinese. “Our Xi Jinping is great!” he told me as we walked slowly to his house. At 92, Xiao hunches slightly and uses a cane, one foot never extending beyond the toes of his other. But he expertly navigated the piles of gravel in the unfinished road. “The poverty elimination campaign and Belt and Road, only our China can do this,” he told me excitedly. “Other countries? Impossible!”

Xiao grew up in the compound of the Catholic church. The more he shared of his story, the more surprised I was at his sanguinity. He studied in seminary and returned to the local elementary school as a professeur. Xiao punctuated our conversation with French. But two years after the Communist victory in 1949, he was labeled an anti-revolutionary and put into a reform-through-labor camp where he served for over 30 years. As we spoke, he took a pink plastic bag from his desk cupboard and slowly unwrapped a collection of cover-bound certificates from various levels of the government. One read:

Certificate of Honor

For your contribution to the work of liberation and socialist construction.

A wheelbarrow dangles three stories above ground as a new house goes up in Cizhong

But it was not a spirit of bitterness that sustained Xiao through his decades of hard labor. “I used to sing,” he told me with a gentle smile. “People thought I was crazy.” He started into an old tune, his voice soft but bright:

Far-flying wild goose

Please fly swiftly

Carry this message to Beijing

This serf who has been freed

Longs to see Chairman Mao

When the political winds shifted in Beijing and Deng Xiaoping was reinstated to Party leadership, Xiao was finally released. He was given a generous monthly stipend and married a young Tibetan woman half his age. Last year, he was given a home among the new Cizhong residences and his stipend continues. Xiao Jieyi is set for life.

Xiao Jieyi, 92, sings one of the songs that brightened his spirits during more than 30 years in a reform-through-labor camp

Another man, surnamed Zhang, is similarly content. “Life and transportation are so convenient now,” he said with satisfaction. “Our national policy is good.” Zhang moved to Cizhong in 1953 and bought a small parcel of land for 2,500 yuan, equivalent to the buying power of roughly $10,000 in today’s dollars. With the Cizhong construction boom, he was able to sell his farmland to the government and now gets disbursements of 500 yuan ($75) each month. For all his farm work, he used to make just 5,000 yuan each year. Now he does nothing and the money rolls in. “These houses used to be made of mud, now mine is four stories. There are 24 people in our family and we own eight cars. Almost everyone in the village has one now.” Like Xiao Jieyi, Zhang is pleased with the turn of events. He has a new house, monthly disbursements and health care subsidies. Who needs farmland?

One man was mixing concrete in the middle of the street, handing buckets up to the workers tiling his new roof. He was relocated from Huafengping, a nearby village on the dam’s floodplain. But his 65-year old mother refuses to move. “They’ll probably make her,” he told me with dread and resignation in his voice. “But we can’t do anything about it. That’s just the way it is.”

Catholics share snacks and chicken-boiled grain liquor in the church courtyard after Easter mass

A banner hangs in the courtyard of the Catholic church:

Listen to the Party, Be grateful for the Party, Follow the Party

In Cizhong, those are your three options. Many in their twilight years are happy with their new houses and content to live month-to-month on their government disbursements. But others are worried. In one fell swoop, the Party has taken their land, destroyed their means of production and ruined their alternative income streams, exchanging them for 15 years of monthly installments and promises of a great rejuvenation of the Chinese people. Worse yet, the locals had no say in the process and no recourse, like candles blown by the state-planned wind. Listen, be grateful, follow.

Such developments are hardly new, of course. The Pulitzer-prize winning journalist Ian Johnson recently wrote about the struggle of his friend Jiang Xue’s grandfather to survive the Great Leap Forward, “a messianic economic campaign initiated by Mao that resulted in more than 30 million deaths by starvation. The family of six had been farmers, but all private farmland and tools had been confiscated, and at the height of the famine they received one bun each day to share.” Jiang’s grandfather starved to death.

Daily bread

As the afternoon turned to evening, Xiao Jieyi placed his certificates back in their pink plastic bag and we began our goodbyes. We grasped hands, less of a shake and more a hold. His were warm and soft, the callouses long healed by the passage of time. “Let’s pray for one another,” he said, still holding my hand. I felt my spirit quicken and my eyes moisten.

“Women de tianfu…” Xiao Jieyi’s small voice began.

I recognized the Lord’s Prayer immediately and when he finished, I responded in kind:

“Our Father in Heaven…

…give us this day our daily bread…

…and forgive us our trespasses as we also forgive those who trespass against us…

…Amen.”

I opened my eyes only to see Xiao’s still tightly shut. He began again:

“Pater Noster qui es in caelis…”

He finished in Latin and continued in Tibetan:

“ང་ཚོའི་ལྷ་ཡུལ་གྱི་ཡབ་ཆེན།…”

And then again in Lisu:

“MU KW ⊥V SI KW TY M ΛW NU B,B=…”

Each time, I tried to follow in my mind and the same phrases stood out to me:

“…give us this day our daily bread…

…and forgive us our trespasses as we also forgive those who trespass against us…”

And it occurred to me that those who had trespassed against Xiao and those who now give him his daily bread are one and the same.