August 30, 2015

Under the banner “Picture stories from here and there,” the Beirut collective Samandal publishes local and international comix. For the uninitiated, comix imply countercultural, illustrated tales for adult audiences. Personal, quirky, and rebellious, comix have no boundaries. The underground art spans from word-heavy narratives in ink to wordless sequential illustrations, reminiscent of 19th century woodcuts (think graphic poems), and everything in between; artists borrow techniques from caped crusaders, cinema, literature, and more.

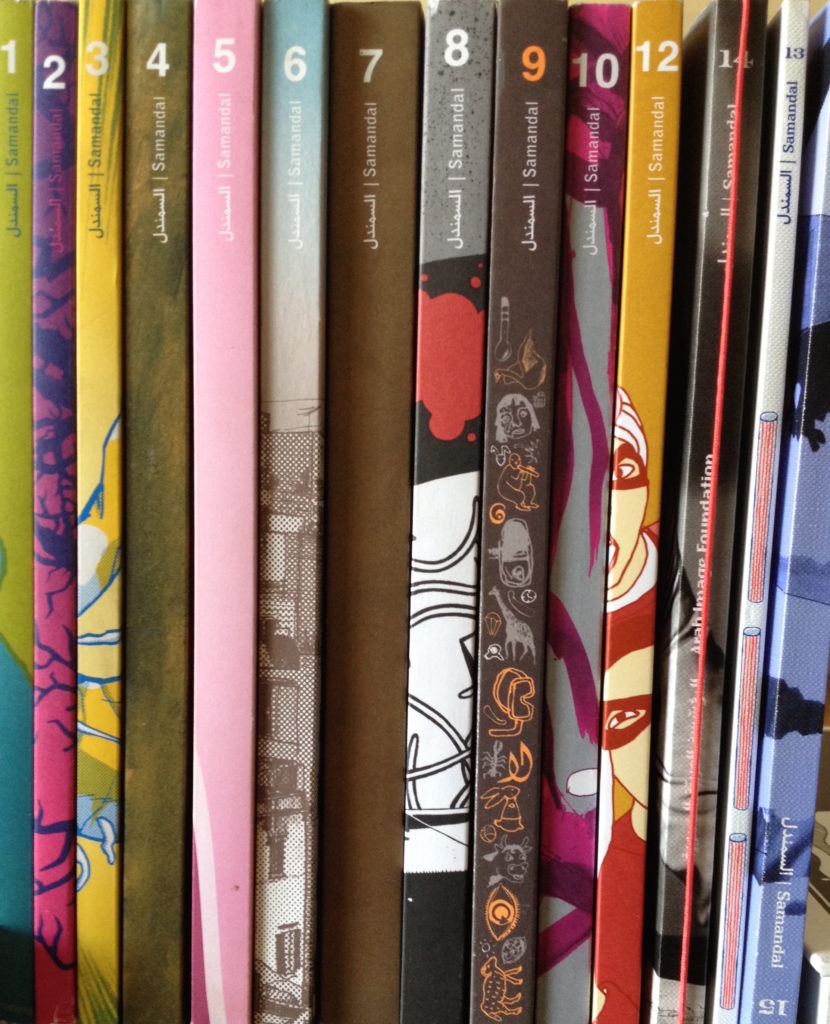

In the United States, MAD Magazine and ZAP spurred the comix turn in the sixties, and artists such as R. Crumb, Harvey Kurtzman, and Art Spiegelman are among the movement’s most influential illustrators. In the Middle East, Beirut is the vanguard of Arab comix. Samandal’s sixteen issues since 2007 have pushed artists in Egypt, Morocco, and Tunisia to follow suit. As Samandal’s coterie of artists experiment in Arabic, French, and English, the ‘zine has carved out space for scores of Lebanese graphic novels and other interventions across the region. “We are the place where new comix are being exposed,” says Lena Merhaj, a Samandal co-founder and children’s book author.

Copies of Samandal are available at more than a dozen of sales points in Beirut. But Issue Seven, published in 2010, has been pulled from the shelves. The theme of the issue was “Revenge,” and in the end Samandal was the object of retribution. A local Catholic organization issued a complaint against three prominent co-founders—comic artists. The General Directorate of General Security summoned them for questioning.[1] Remarkably, they continued to publish new issues during four years of legal trouble. Their appeal failed, however, and earlier this year Samandal was compelled to pay US$20,000.

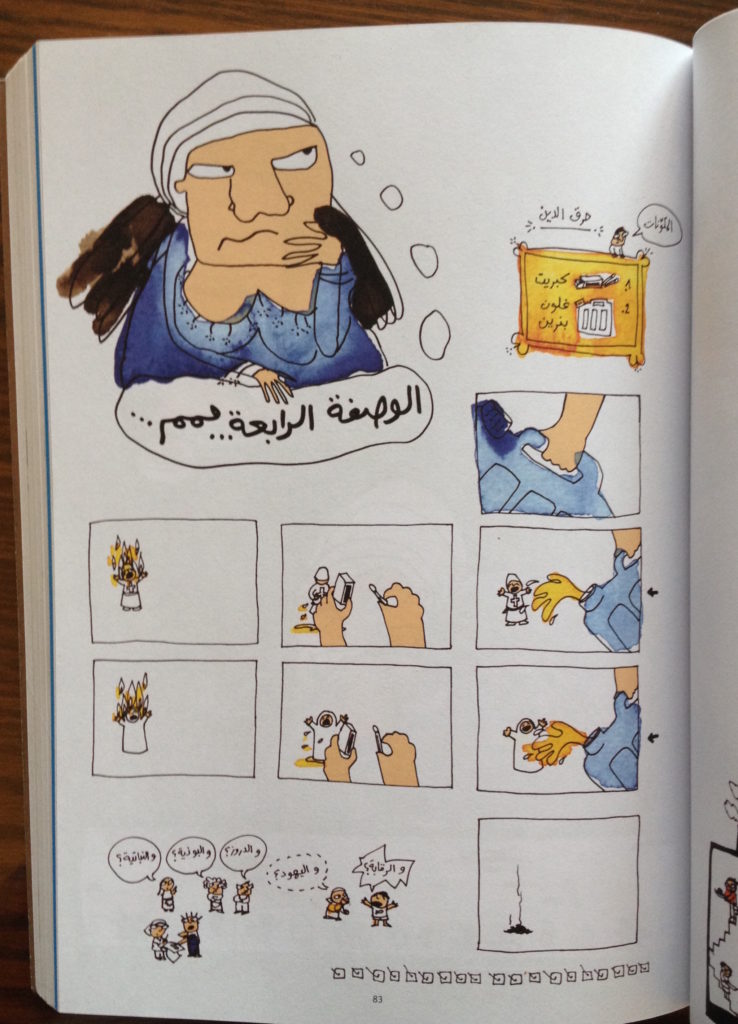

The comics under scrutiny were undoubtedly crass. Among the 35 vignettes in the Revenge issue, Belgian artist Valfred offended with illustrations of early Christianity in a comic entitled, “Ecce Homo.” It begins with a Roman legionnaire gazing at a crucified Jesus, a raw sketch in thick ink; the soldier says, “It is you who are the faggot,” in French. A few pages later, after a battle scene, two Roman soldiers engage in oral sex. In another comic from that issue, Merhaj drew, “Lebanese Recipes for Revenge,” in Arabic, with a sorceress explaining her secrets. Merhaj dug up a copy of the issue from the ‘zine’s dusty storage room. “It’s this fucking page,” she says, pointing at a small priestly man with a cross hanging around his neck. Then, he is drenched in kerosene and lit by a matchstick. The recipe explains “[How to] Burn Religion.” The dialogue in the bottom left corner of the comic, is an irreverent disclaimer:

“And [what about] censorship?” says a little man.

“And the Jews?” another replies.

“And the Druze?” says another.

“And the Buddhists?”

“And the vegetarians?”

This equal-opportunity offense apparently brought no comfort to Beirut’s Catholic minority.

The censorship of Samandal might befuddle the casual observer who pictures Beirut as a city of revelry and laissez-faire, the dysfunctional Lebanese state apparatus lurking in the backdrop. Not so fast. “People have the impression that Lebanon is very liberal, but that is only true in comparison to the very extreme conservatism of the surrounding countries,” artist Omar Khouri, a Samandal co-founder, said in an interview last year. “In truth, Lebanese censorship is quite strict, while keeping the guidelines very ambiguous and up to the discretion of General Security…”[2]

As elsewhere in the region, the boundaries of acceptable speech are nebulous. For instance, in 2007, General Security banned Marjane Satrapi’s graphic novel Persepolis for offending Iran.[3] Yet a limited-run Arabic translation of Satrapi’s illustrated memoir is on sale at Plan BEY, a bookshop and gallery; English copies are available in Virgin Megastore’s extensive comic section and other fine booksellers. Similarly, in 2004, the Catholic Information Center protested to the Security Directorate about Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code, and the state proceeded to ban the bestseller. Nonetheless it is easily found at the popular chain Librairie Antoine.[4]

Lebanon’s print media falls under the purview of a 1962 Publications Law and more recent decrees and amendments, which all contain vague language. In short, General Security reserves the right to yank publications “perceived to endanger security, upset national sentiment, damage public morals, or incite sectarian tensions,” according to the local watchdog March, which curates the Virtual Museum of Censorship.[5] Such an equivocal mandate has proved burdensome for artists, including the eminent musician Marcel Khalife. The country’s highest Sunni authority, Dar Al-Fatwa, issued a complaint against him for singing about the Prophet Joseph, lyrics from the poem “I am Joseph, Father,” by Mahmoud Darwish. (Khalife was ultimately acquitted.) According to Khouri, “Politics, religion and sex are generally topics that one is advised to steer clear from if you want to avoid trouble with the law, yet they are three of the very few topics that are worth exploring if you are an artist.”[6]

Going forward, how will Lebanese artists approach vexing topics? Until now, Samandal has glibly flaunted its “18+” distinction, which has served as a cover for the artists’ forays into tricky territory. “We’re lucky that a lot of stuff can go under the radar, since no one takes comics seriously,” Hatem Imam, another co-founder, told the Mideast art magazine Bidoun in 2009, when the ‘zine was four issues in.[7] By now, the age of innocence has ended.

Samandal had to beg and borrow for the US$20,000 fine, and now the nonprofit collective carries a huge debt. They plan to release a statement on the case, a flippant retort headlined “How Samandal Ruined My Life.” Members declined to share an advance copy of the statement, which their attorney is reviewing. Most surprisingly, Samandal has kept the entire ordeal under wraps. In other instances of censorship or lawsuits in the region, artists tend to launch grassroots campaigns and online petitions, rallying Human Rights Watch, PEN, and other free speech defenders. This case has only been briefly mentioned in a blog post here, a think-tank report there. That self-imposed embargo pertains to the artists’ own surprise: they thought that the church’s lawfare might be managed behind the scenes. Says Merhaj, who illustrated the bewitched Jesus, “When it happened, we didn’t think we would lose.”

Lebanon needs “a little more consideration for artists in the country,” she explains. “There is no artist support whatsoever.” Merhaj would depart days later to speak at the Shubbak Festival, an Arab culture biennale in London: “I go represent my country everywhere. I say I’m from Lebanon. But what is Lebanon offering me?”

From Comics to Comix

To understand the roots of Samandal and the rise of Arab comix, we must first turn to the moment when it spun off from the world of children. That shift began during the Lebanese civil war.

“Why should I draw comics for kids?” asks George “Jad” Khoury, as he sips a glass of red wine in the elegant Café Diem. Indeed it is difficult to imagine illustrating for children as militias, car bombings, and an Israeli siege ruptured the Middle East’s most glamorous metropolis. A variety of paramilitary forces engaged in “the sectarian war,” as Jad calls it, which decimated the city’s landscape and people. From 1975 to 1990, at least 120,000 were killed according to the United Nations. Amidst war, Lebanese political cartoonists—many of whom were under threat themselves—unpacked narratives of geo-political strife. But Jad sought a tool to transcend traditional journalism.

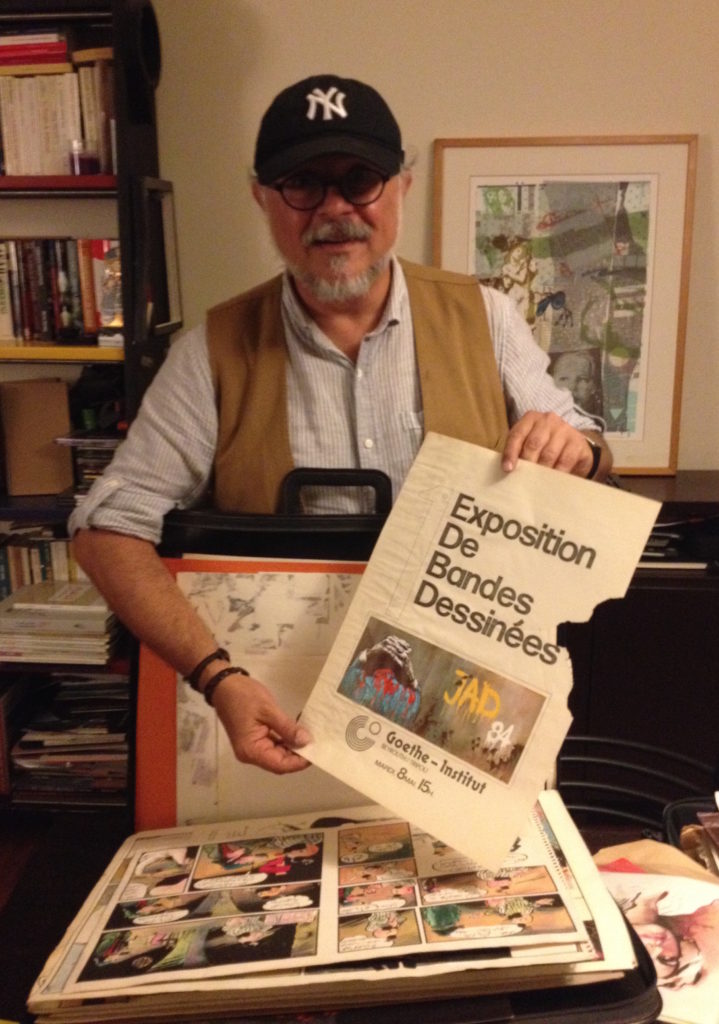

Jad directs the animation department of the local network Future Television and is a fine arts instructor at the Lebanese American University in Beirut. But he is better known as the pioneer of the Arab comix movement.

For nearly a century, Beirut’s newsstands and booksellers have provided a fertile culture of illustrated literature. Local political cartoons date back to the 1920’s, when caricatures of personalities and politicos were common features of broadsheets. Of note is the satirical magazine, Al-Dabbour, which was founded in 1922 (it closed in 1978, and re-launched in 2000). With traditional caricatures of politicians—fat, exaggerated faces sitting on skinny bodies—Al-Dabbour publishes political commentary similar to its European and North American counterparts, often with lofty metaphors and too many labels. (In a publication for local readers, labeling a map “Lebanon” seems superfluous.)

Regarding children’s comics, in 1955, Bissat El-Reeh was published in Beirut, a few years after the kid’s magazine Samir sprung up in Egypt. As early as 1964, Superman in Arabic appeared in Beirut bookstores, shipped from Egyptian printers. Weekly translated editions of Superman—as well as other heroes and cartoon characters, such as Lulu—became staples of children’s reading diets and began being published in Beirut, too. Lebanon is where superheroes and other famous Western characters took a foothold in the Middle East.[8] Jad grew up reading Tin Tin and Asterix. In an ecosystem of comics and caricature, the opportunity for experimentation presented by alternative comix was a natural step.

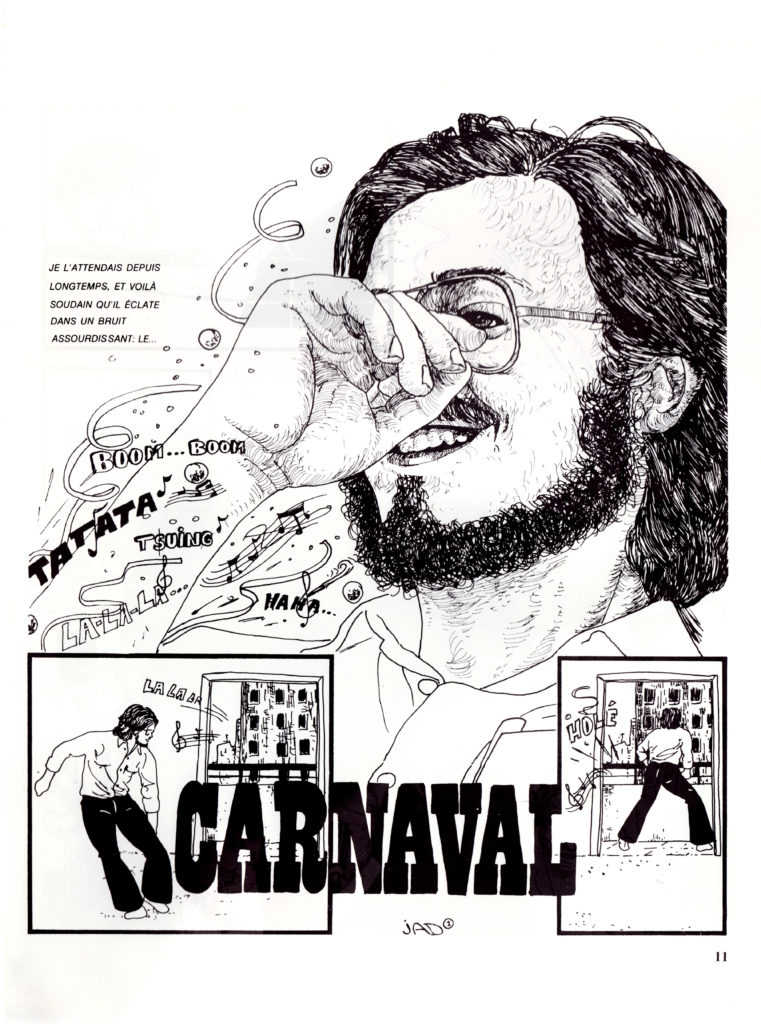

Jad quit his studies at the Académie Libanaise des Beaux-Arts to try his hand at the emerging art form. He hesitates to say he is the first to apply comic lens to grown-up themes. But his 1980 album Carnival, a three-act dream of the war, is certainly a milestone for Arab comix.[9] For Jad, the shift was much more than technical adjustment. “Comix are not a medium. It’s a genre of art, and you have to express yourself,” he says, adjusting his black baseball cap, a ponytail hanging through the back.

“The war is the major if not decisive factor in shaping my artistic choices, and making this comic path, and helped comics as a genre of art to flourish,” he says. Even Jad’s origin story is rooted in the conflict. He had written journalistic articles under his given name, George Khoury, and recognized that the name itself projected sectarianism: “No way that George would be Muslim, or Khoury which means priest.” He sought “a neutral name,” one that could easily be pronounced by Western audiences. It is common for a comic artist to draw under a nom de plume. And, importantly, he liked the way “Jad,” looked as a signature.

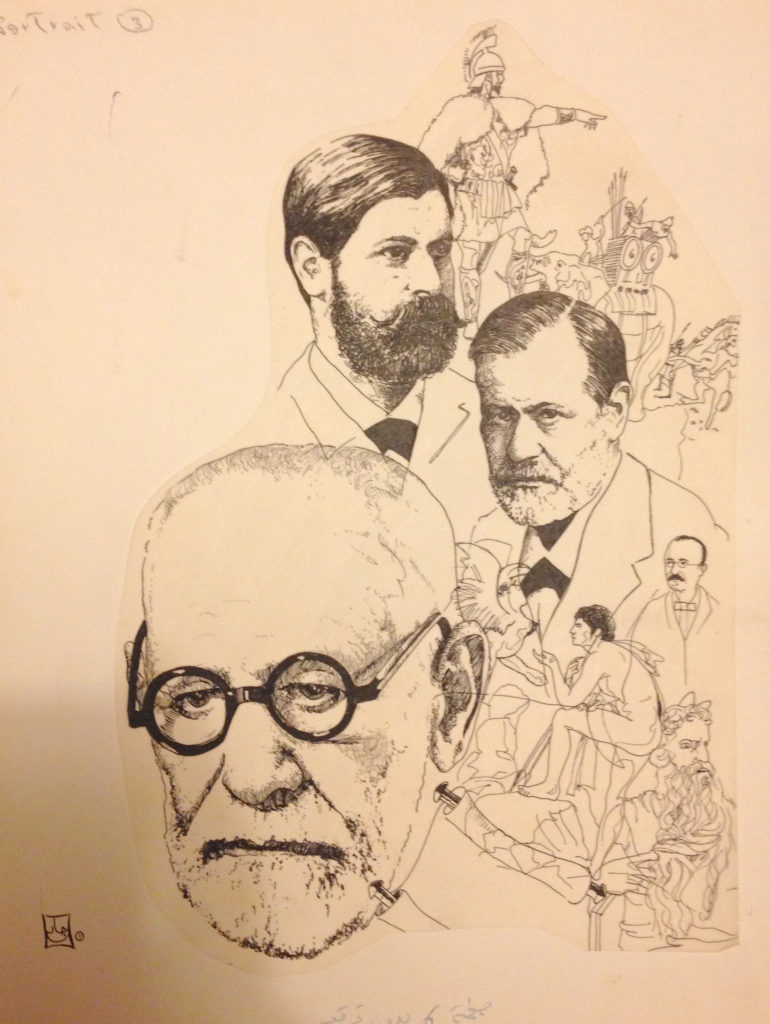

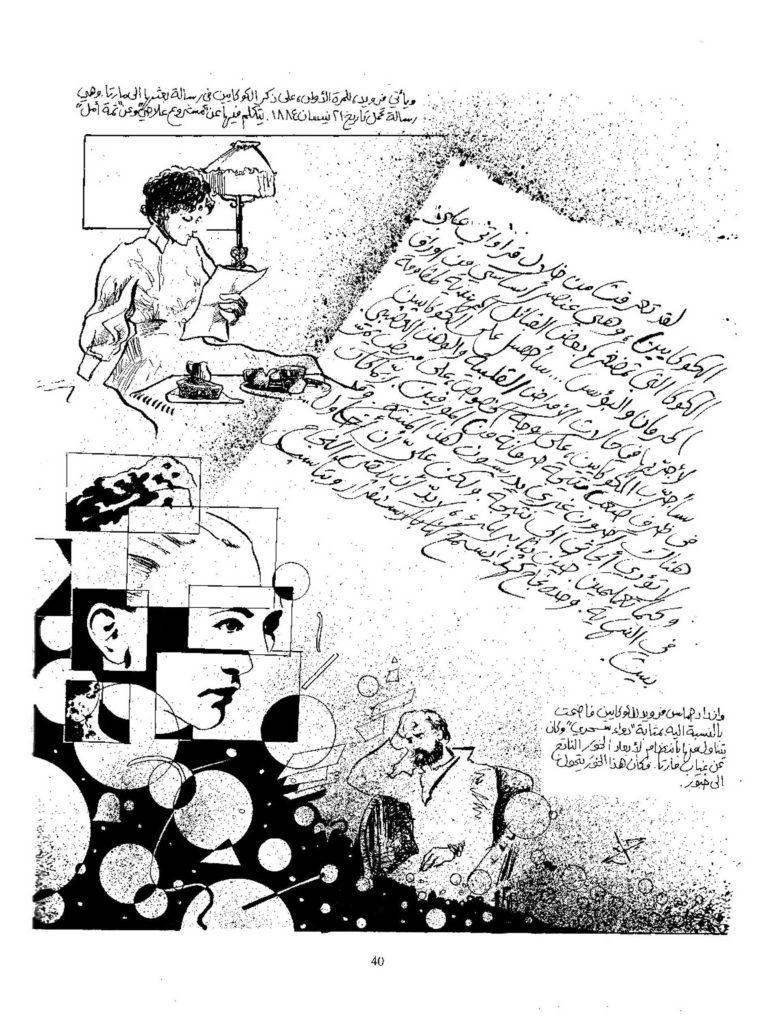

After the Israeli invasion, in 1983, Jad collaborated with psychiatrist Ralph Rizkallah in illustrating Freud, an unconventional autobiography of the father of psychoanalysis, in Arabic. Drawing a series of ten vignettes from Freud’s life, Jad worked through the war by focusing on Freud’s issues as a minority under threat in a repressive society—a mechanism for questioning the artist’s own identity. The narrative uses devices of superhero comics, such as bold lettering and nonlinear frames that meld into one another, to express Freud’s interior life. There are extended dream sequences, which only a comic could capture. The carefully researched narration compliments the ghostly and surreal illustrations.

Jad matured as an artist by connecting with the field’s top illustrators. At 24-years-old, he attended the Angoulême International Comics Festival, the preeminent gathering of global cartoonists. “I met big names—Wolensky, Cabu, who was my mentor, the guy who took my hand and told me I would be someone,” he says. (Both Wolensky and Cabu were assassinated in the January 2015 attack on Chalie Hebdo in Paris.) “In that era, comix in the West were still fighting to be born,” Jad says, remembering the zeal for experimentation he was exposed to in France. There was another important aspect to these trips abroad. “Unfortunately in the Arab world you are only recognized when foreigners recognize you,” he says.

By 1984, with the support of the Beirut branch of the Goethe Institute, he had founded Jad Workshop. It was at the drawing board where he met his wife, Lina Ghaibeh, who participated in the workshop along with her twin sister, May—at a two-for-one discount. (“Till now, Lina calls me Jad, not George,” he says with a smile.) Of the initial sign-ups, ten dropped out when they realized the workshop was not a simple drawing class—no, this was about testing narrative forms, re-appropriating the style of superheroes and children’s comics to new ends.

“War changes routines,” says Jad, who would draw by candlelight alongside friends, during power-cuts. Back then, Jad would taunt attendees at artsy events and openings, telling them, “Fine art is dead, and comics is the new fine art.” He thought that paintings had become just like carpets, another tacky and commercialized handicraft.

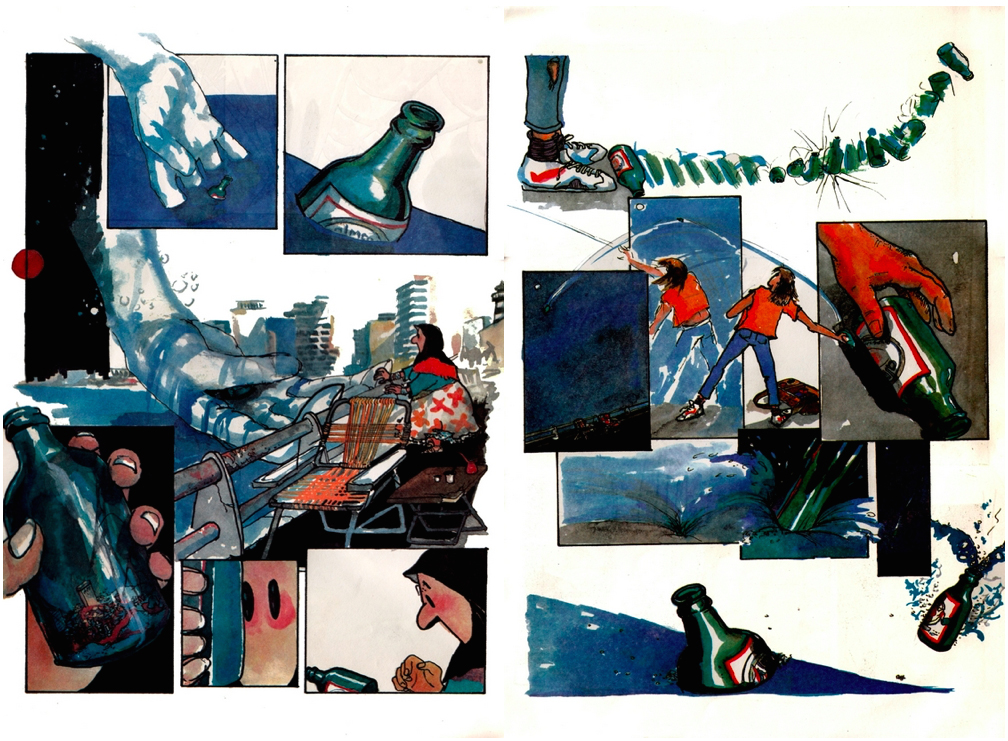

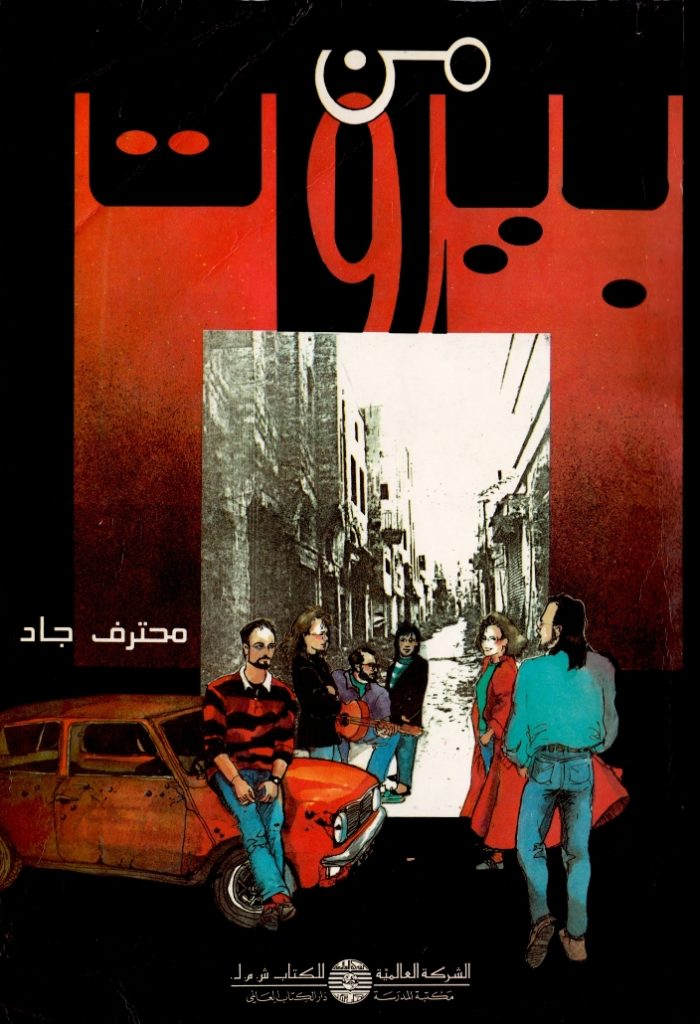

In 1989, Jad Workshop published From Beirut, an influential comic comprising six war accounts by six different artists. The captions and dialogue, all of which Jad inked in flowery Arabic calligraphy, fuse together bloody scenes more gruesome than any action saga. From Beirut is a testament to tenacity in the face of death. The comic teases out the incongruity of new friends being made and music being played on the corniche as bombs fall. On one page a couple kisses; on the next a building crumbles.

Lina Ghaibeh is now an associate professor in the department of architecture and design at the American University of Beirut, where she teaches animation. She is also the founding director of the university’s Mutaz and Rada Sawwaf Arabic Comics Initiative, the first of its kind in the region. (More on Sawwaf later.) Its mission is “to elevate and facilitate the interdisciplinary research of Arabic comics, promote the production, scholarship and teaching of comics, and develop and maintain a repository of Arabic comics literature.” Together, Lina and Jad have begun compiling a database—from the children’s comics of the 1950’s onwards, to newer adult graphic novels. On Jad’s tablet are hundreds of them: Hezbollah and Maronite cartoons for children, progressive Lebanese superheroes, crime noirs, experimental memoirs, and his own works.

Carnival and From Beirut are both out of print, but the narratives echo through the city as comix have entered the Lebanese mainstream. Since 1997, Académie Libanaise des Beaux-Arts—where Jad dropped out—has offered a masters of arts in illustration and bande dessinée. Adult comic books in Arabic, English, and French are on sale at scores of bookstores in the Lebanese capital. Blue-chip art galleries display illustrations and publish illustrated booklets. And in 2010, the Bibliotéques et Médiathéques du GrandAngoulême, as part of the international comic festival, hosted a retrospective of Jad’s illustrations.

Jad continues to draw but prefers not to publish his latest work—“not because of censorship, but because [of] me, personally….” he explains, noting that when drawing for a Lebanese newspaper, one must make compromises, whether that be dumbing down issues or expressing political critiques with subtlety. “I don’t like detours,” says Jad.

An Amphibious Experiment

Two decades after the civil war, Beirut is a city still under construction. Rather than fighter jets, the shrieks of scraping metal disrupt the peaceful city. On almost every corner, there are cranes, bulldozers, and men at work. Meanwhile, the grisly civil war in Syria is a present absence: of course there are lethal spillovers, along with inflows of refugees. But the weight of Syria’s war is somehow obscured by Beirut’s new modernism, the construction of Dubai-meets-Brooklyn in neighborhoods ravished during the capital’s own war.

The city lacks a modern art museum, but spaces for creativity abound. I visited many contemporary art galleries; cafes that sell books and art; and bookstores that sell coffee with a shot of creative energy. Each space hosts public and private events of multimedia proportions. “These spaces don’t want to be specialized,” says Kirsten Scheid, an anthropologist at the American University of Beirut, who likens these hybrid domains to comix, which assimilate myriad art forms, movements, and politics. The café-cum-gallery, or the gallery-cum-café, provides “all of these aspects that would prepare you to deal with the world,” she says. And many of them sell comix—the vast and frenetic works of prominent artist Mazen Kerbaj, comic memoirs by Zeina Abirached, limited-run publications from an array of artists, and always Samandal.

The name Samandal means “Salamander” in Arabic. In the first issue Fadi “Fdz” Bakri illustrated an amphibian discussing the ‘zine’s manifesto: the salamander trespasses between the land and sea, just as comix traverse the written and the illustrated. A little larger than a pocketbook, each issue of Samandal costs between US$2 to $5 (except for issue sixteen, which is twice the size and in color, and costs around $20). Three decades since Jad Workshop, Beirut is still exploring new tactics of storytelling, new stories altogether.

Samandal attracts illustrators from Europe and North America, a hodgepodge of comics initially gathered from open calls. For recent issues, the inner circle has assigned leading artists to develop themes. Issue Sixteen, edited by the Belgium-based Lebanese artist Barack Rima and published last year, focused on genealogies. The next issue, a meditation on geographies, is being edited by Joseph Kai, a 26-year-old illustrator who attended Samandal’s Issue Zero launch party in 2007 and has been obsessed since. He described the volume, which is due out later this year, as heavily influenced by the geo-political wars and movement of peoples in and among Lebanon, Palestine and Syria—“a stroll in comics through the landscape of this part of the world, be it real or imaginary.”

In addition to its varied aesthetics (from abstract art to pastiches of hundred-year old photographs archived by Arab Image Foundation), Samandal’s publishing approach is novel. First, the ‘zine is licensed under creative commons: it’s free to republish, disseminate, or “remix” the works, so long as it is for noncommercial purposes and the new works also fall under flexible licensing. Second, Samandal has cooked up the flippy page, “an upside-down technique… to deal with the two opposite reading directions of Arabic and English.”[10] Rather than laying out the Arabic on the cover and English/French on the back, the three languages are interspersed; the reader is instructed to flip the book when the next chapter is in a different language. Plus, all the English and French comics have Arabic translations at the end of each issue. Might this be a lesson for how multilingual Beirut can reconcile three tongues?

For his part, Jad has reservations about Samandal, which he describes as featuring a range from professional comics to amateurish works that belong in a fan-zine: “This thin line, I think they broke it.” Jad holds great respect for the ‘zine’s founders, the inner-circle of Lebanese comic artists as well some of the international talent they have attracted. His primary critique is that Samandal is geared toward an intellectual and elitist audience, which means they are widely known on international comic scene but less so in the Lebanese marketplace of ideas. Jad’s general rule for cartooning: “Don’t be pretentious.”

Meanwhile, Arab comix publications are popping up across North Africa and the Levant. Yet organizing the pan-Arab comix movement remains elusive, primarily because of distribution. Books don’t easily cross borders, and each country in the region has its own censorship regime (“At one point, you could not bring Samandal into Jordan. It’s dangerous,” says Merhaj.) Since the comic business is far from lucrative, publishers avoid printing alt-comix in the first place, let alone like-minded narratives from neighboring countries. Of course it’s even more challenging for artists themselves to obtain visas and convene. For now, Samandal’s artists meet their counterparts across Europe and the Middle East at comic cons and literary festivals, ferrying publications in suitcases and exchanging new issues.

A Patron of the Comic Arts

In its jumble of languages and aesthetics, Samandal is a departure from the classic role of political cartoons, which tend to be tightly focused on the day’s news and the immediately gettable. Yet political cartoons continue to influence experimental comix, and the boundaries between those two worlds are becoming increasingly fluid.

“The history of Arab cartoons is very rich,” says Rami Khouri, a syndicated political columnist and senior policy fellow at the Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs at the American University of Beirut. “[It’s] one of the few places where people could really let their voices be heard in autocratic regimes.” But few books tell that history. Political cartoons are, by nature, ephemeral, and national archives difficult to access. To read those fleeting pages of past decades, one must secure entry to the annals of newspapers, which are often haphazardly documented and sometimes-missing whole years. As for monographs about Arab cartoonists, such books tend to be published in a single edition—often only after an artist’s death. Rummage through a second-hand bookshop, and perhaps one or two will be tucked away. Few books or websites present the entire region’s vast comic output, whether from a historical perspective or amid its contemporary outburst.

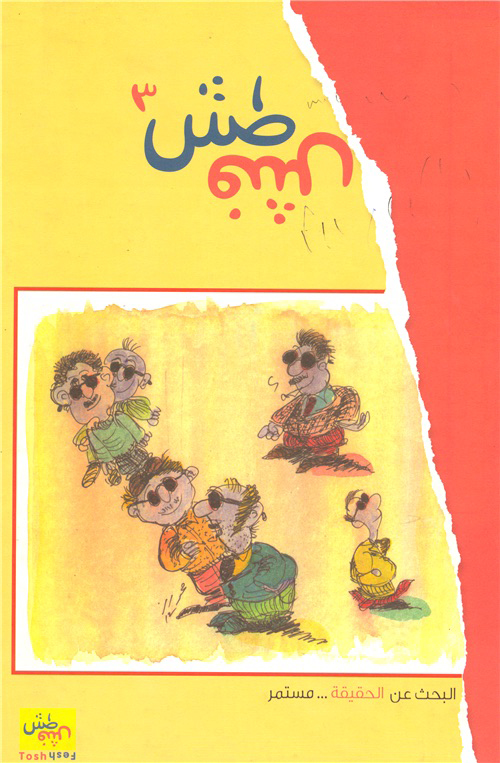

Enter Moaz El-Sawwaf. An engineer who made his fortune working with the Saudi-based Binladin Group and other construction companies in the Gulf, Sawwaf established a non-profit organization, Tosh Fesh, which supports budding Arab political cartoonists. His team has published three books that document the work of Arab illustrators. The outfit is providing a vital service by amassing illustrations by artists who otherwise might be forgotten despite their notoriety in the region. While Arab comics for adults and children boom, Sawwaf is the only person investing in an industry that, for many cartoonists, remains a labor of love. Tosh Fesh has also released original comics, and their latest publication is a highbrow monograph, in Arabic and English, honoring Lebanese political cartoonist Mahmoud Kahil, who passed away in 2003. Furthermore, Tosh Fesh is partnering with a Jordanian animation company, Kharabeesh.

As for the meaning of “Tosh Fesh,” I have not been able to find those words in any Arabic dictionary. Jad the comic artist told me that it’s eighties slang for yadda yadda or gobbledygook. It is also the name of Sawwaf’s series of comics from that era.

Sawwaf funds the newly established American University in Beirut’s Arab Comics Initiative—named after him—as well as the initiative’s Mahmoud Kahil Award. Since April, hundreds of Arab artists submitted works to the first iteration of the contest. There are five categories (editorial cartoons, graphic narratives, comic strips, graphic illustrations, and children’s book illustrations), which each offer $5,000 to $10,000 prizes. A jury of renowned illustrators, including the International New York Times’ Patrick Chappette, will present the award at a November symposium. The gathering’s theme will be the personal and the memoir, a pertinent starting point for new debates about the art form.

I arrive for a meeting at Tosh Fesh headquarters, steps from a large shopping mall, and leave my ID with three armed guards in an outpost. More guards amble through the pedestrian passageway in the hot sun—the president of the parliament lives around the corner, and the neighborhood is always on lockdown. Down the sidewalk and on the fourth floor, Tosh Fesh’s office is out of a design magazine: simple glass walls and a large Ikea-esque table in the conference room. Famous Arab cartoon images adhere to the walls: a cat showing off her biceps, by Tunisian cartoonist Nadia Khiary; a cityscape by Egyptian comic artist Mohammed Shennawy; a flying man from Kuwaiti creator Naif Al-Mutawa’s Islamic-inspired superhero series “The 99”; a life-size speech bubble that reads “Arab Comics”—in Arabic, of course.

Two staffers pour over the fourth book in the Tosh Fesh series, translating texts, a task that always proves challenging. How do you translate “G-spot” from French to Arabic? The answer is to dodge it, even when it’s a cartoon cat’s punch line. In a 2013 strip by Khiary, better known as Willis from Tunis, a male cat taunts a female compatriot about the Islamist An-Nahda party’s political dominance and the end of feminism. The male cat harps: “Equality is over. Castration is caput. Monogamy is over. G-spot—done!!!” The female cat replies, “And beer is done, too!” This strip will appear alongside other works by emerging and classic cartoonists in the fourth volume of Tosh Fesh.

As with all previous volumes, Sawwaf has personally chosen all of the comics in the forthcoming edition. He also draws the covers. It’s quite a contrast to the collaborative format of Samandal, a space of jarring, divergent stylings that leap off the page, narratives that span from professional to amateurish. The hardback volumes of Tosh Fesh are polished. But, as Tosh Fesh continues to publish new books, what might emerge is a much-needed encyclopedia of the vibrant yet understudied art.

Comix as Politics

The medium of comix lends itself to internal reflection and worlds of fantasy. Such stories can be punchier than political cartoons, but just as often they are simply meditations on the personal and the unreal. Much of the comic art on display in Beirut, like any European capital, does not overtly tackle the disturbing political violence of the day. (As an aside, I must return to Beirut to interview Syrian cartoonists living in exile.) Nonetheless, in a city that lived under siege for about two decades, a city that has always been under the media’s microscope, personal narratives represent a different strand of radical expression. “Politics affect my work indirectly,” Samandal’s Joseph Kai wrote me by email. “Conflicts and wars in the region are subjects that never leave the back of my mind.”

By the same token, Samandal co-founder Omar Khouri has acknowledged the instinct to sidestep political issues and slip into escapism. In an interview last year, he told blogger and academic Elias Muhanna:

For quite a long time, I was one of those artists who avoided politics in both their work and their everyday life. Growing up in Lebanon, politics in my mind was always equated with war. Engaging in any political act was only a way to reinforce one’s prejudices against their fellow countrymen and tribal fidelity to their narrow-minded warlord leaders. In many ways, the situation remains unchanged to this day. I believed that avoiding “politics” and anything to do with it was the only way to step out of that vicious circle of hatred afflicting not only my country, but the rest of the world as well.

However, after spending five years in the States, then returning to Beirut, I came to realize that politics was an implied aspect of everything I did. I was beginning to understand that even my refusal to engage in any political act or discussion was in itself a political statement.[11]

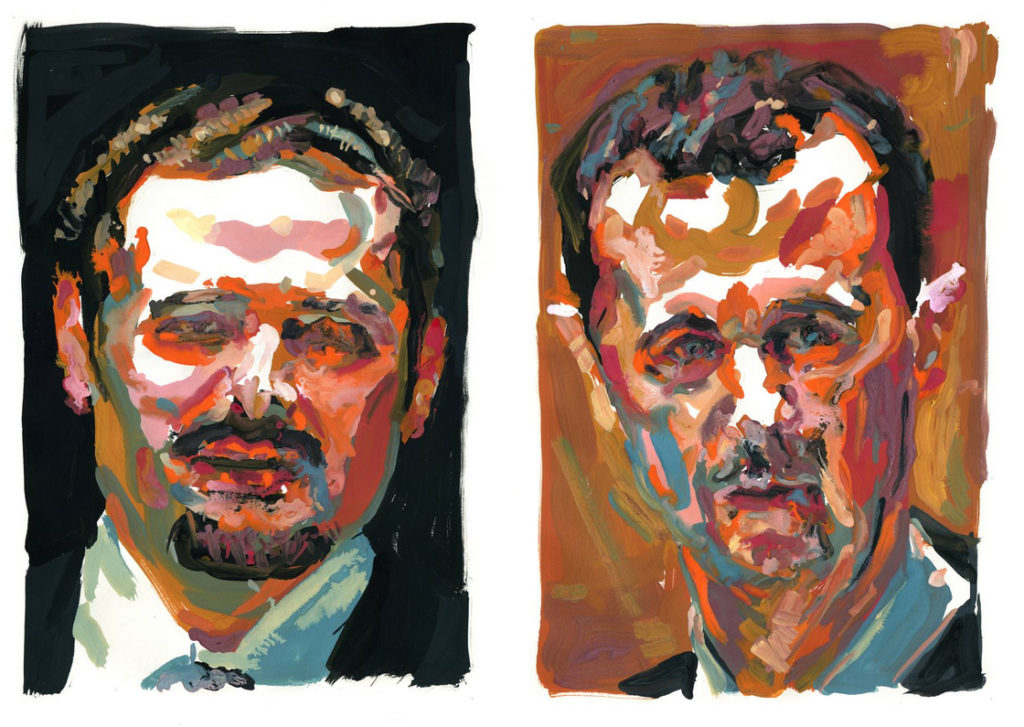

That development is evident in his paintings, where Khouri transcends caricature and fine art by taking risks. With deep colors and an effortless attention to detail reminiscent of American artist Chuck Close, Khouri has painted portraits of Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad, Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah, and former Lebanese President Saad Hariri, among others. (As recently as 2012, a Nasrallah caricature was censored for its sarcasm[12].) The brushstrokes composing the famous faces force a double take: is that the Assad we know from CNN? Khouri described the portraits as “an attempt to depoliticize their image[s] and highlight the human aspect of their nature in search of aspects in their personalities that one can connect with on a more basic level regardless of their political views.”[13] Indeed this act of de-politicization acknowledges that certain images are censored, that leaders find ways to protect their own faces from caricature.

At the same time, comix are entering the mainstream. Barrack Rima, a Samandal contributor, has used his page in the Lebanese newspaper Al-Akhbar’s Culture section to tell narratives that go beyond the single frame editorial cartoon. Earlier this year, he re-published cartoons from the world’s cartoonists as they reacted to the Charlie Hebdo attack. He translated Joe Sacco’s Guardian comic to Arabic; he added to the conversation the Egyptian cartoonist Makhlouf’s spoof of the Kouachi brothers’ worldview. Equally significant is Rima’s Arabic comic “Before-Noon Nap,” which leads Samandal’s fifteenth issue (January 2013). He recounts a nightmare in which he traveled from an unknown land into Lebanon. Chased by lions and haunted by the media—though when it was republished by the New York comic magazine World War III Illustrated, Rima insisted his work, “wasn’t political.”[14]

It’s not that contemporary Lebanese comix are apolitical, or that there isn’t outrage at the region’s conflicts. In fact, progressive activism is a fundamental, if understated, quality of the comix movement. Yet the form lends itself to meandering approaches. By now, the role of the political cartoonist has been cemented: to comment on the daily machinations of government and trends in society, chronicling, witnessing or joking about the little data points that comprise a bigger narrative of politics as we live it. Across the Middle East, the role of comix and the comic artist are still being defined.

[1] Nizar Saghieh et al. “Censorship in Lebanon: Law and Practice,” The Censorship Observatory, January 2012. P. 121. Available at: http://lb.boell.org/sites/default/files/2010._censorship_in_lebanon-_law_practice_en.pdf

[2] Elias Muhanna. “An Interview with Omar Khouri,” Qifa Nabki, 8 November 2014. Available at: http://qifanabki.com/2014/11/06/an-interview-with-omar-khouri/

[3] “Persepolis.” The Virtual Museum of Censorship.” Available at: http://www.censorshiplebanon.org/Categories/Books/Persepolis-second-954

[4] Hannah Wettig. “Lebanese Authorities Ban The Da Vinci Code,” Daily Star, 16 September 2004. http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Lebanon-News/2004/Sep-16/5334-lebanese-authorities-ban-the-da-vinci-code.ashx

[5] “Info,” The Virtual Museum of Censorship, available at: http://www.censorshiplebanon.org/Info.

See also: Jad Melki et al. “Mapping Digital Media: Lebanon.” Open Society Foundations, 15 March 2012. Available at: http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/mapping-digital-media-lebanon-20120506.pdf

[6] Muhanna, 2014.

[7] Negar Azimi. “Super Friends: Samandal Interviewed by Negar Azimi,” Bidoun, 2009. Available at: http://www.bidoun.org/magazine/18-interviews/samandal/

[8] Henry Matthews, a researcher at the American University of Beirut, has written the Encyclopedia of Lebanese Comic Books (2010), exploring mostly children’s comics and superheroes. See: “Talking to Henry Matthews,” Now Lebanon, 27 March 2008. Available at: https://now.mmedia.me/lb/en/interviews/talking_to_henry_matthews

[9] Even though it was written in French, I would argue that Carnival is an Arab comic and indeed a seminal work in the emerging canon. As scholars Allen Douglas and Fedwa Malti Douglas write in their 1994 book, Arab Comic Strips: Politics of an Emerging Mass Culture (Indiana University Press): “…[N]ot all Arab strips are written in the Arabic tongue. For historical reasons, some of the most creative Arab strips are produced in French.” (Page 4.)

[10] “Flippy Page Comic Workshop,” Shubbak Festival, July 2015. Available at: http://www.shubbak.co.uk/flippy-page-comic-workshop/

[11] Muhanna, 2014.

[12] In February 2012, the prominent political cartoonist Pierre Sadek rendered Nasrallah in a pop art style. Hezbollah urged Al-Joumhouria newspaper to remove the cartoon, but Sadek denied that the paper took it down. See “Pierre Sadek Resonds to Campaign Against Him: Caricature Does Not Hold Any Personal Contempt for Nasrallah” [Arabic], Skeyes Media, 28 February 2012. Available at: http://www.skeyesmedia.org/ar/News/Lebanon/1064

[13] Ibid.

[14] Press release for World War III Illustrated, #44, February 2013. Available at: http://www.worldwar3illustrated.org/i/ww3-44-preview.pdf